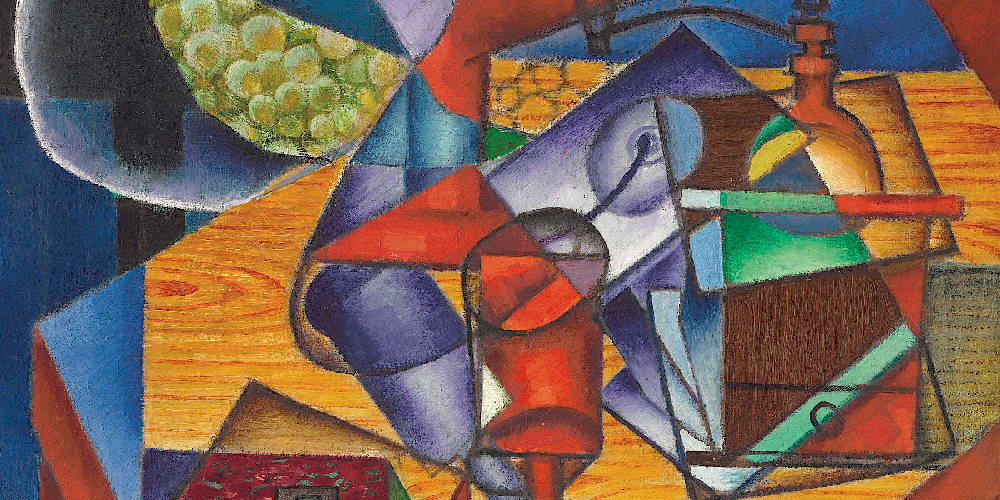

Cubism, an avant-garde movement in the early 20th century, profoundly transformed European art, extending its influence to music, literature, and architecture. This artistic revolution involved breaking down subjects into abstract forms, presenting them from multiple perspectives, contrary to the traditional single viewpoint approach. Paris, especially Montmartre, Montparnasse, and Puteaux, became the epicenter of Cubism during the 1910s and 1920s.

Pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, the movement also welcomed talents like Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Robert Delaunay, Henri Le Fauconnier, Juan Gris, and Fernand Léger. Cubism drew inspiration from Paul Cézanne’s late works, evident in the representation of three-dimensional forms. Cézanne's influence was accentuated by retrospectives held in Salon d'Automne, starting in 1904.

In France, Cubism spawned various offshoots such as Orphism, abstract art, and later, Purism. Its impact was profound, sparking movements like Futurism, Suprematism, Dada, Constructivism, Vorticism, De Stijl, and Art Deco across different countries. These movements shared common elements: the fusion of past and present, simultaneous representation of different views of the subject, and the simplification of geometric forms. Picasso's technique of constructing sculptures from separate elements also inspired Constructivism, linking these movements through their innovative approaches and thematic explorations

1. History of Cubism

Cubism, a groundbreaking art movement in early 20th-century France, is often divided into distinct phases by historians. One classification, Analytic Cubism, spanned from 1910 to 1912, marking a radical and influential period. A subsequent phase, Synthetic Cubism, continued until approximately 1919, giving way to the rising popularity of Surrealism. English art historian Douglas Cooper proposed an alternative categorization in his book, "The Cubist Epoch". He identified "Early Cubism" (1906-1908) as the movement's initial development in Picasso and Braque's studios. The phase termed "High Cubism" (1909-1914) saw Juan Gris rise as a prominent figure. Cooper labeled the period from 1914 to 1921 as "Late Cubism," signifying its final avant-garde phase. Cooper's specific terminology highlighted intentional value judgments within Cubist art.

1.1 Proto-Cubism (1907-1908)

Cubism emerged as a groundbreaking artistic movement from 1907 to 1911. A pivotal moment occurred in 1907 with Pablo Picasso's painting "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon," often seen as a proto-Cubist work. In 1908, art critic Louis Vauxcelles described Georges Braque's exhibition, noting his geometric simplifications, which he called "little cubes." Braque's 1908 series "Houses at L’Estaque" further highlighted this style. The term "Cubism" was officially recognized during the Salon des Indépendants in 1911, featuring artists like Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, and Fernand Léger. Picasso was acknowledged as Cubism's inventor by 1911, although debates about the movement's core artists and interpretations of space persisted. Some, like Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, argued that Cubism emphasized the canvas's flatness despite its intricate depiction of space. Over time, broader interpretations of Cubism included artists associated with the Salon des Indépendants and the Section d'Or group. Scholar John Berger emphasized Cubism's essence as a mechanical diagram, a visible representation of invisible processes and structures.

1.2 Early Cubism (1909-1914)

In the early 20th century, Cubism, a revolutionary art movement, had two distinct factions: the Kahnweiler Cubists and the Salon Cubists. Kahnweiler, a devoted art dealer in Paris, supported Picasso, Braque, Gris, and Léger, providing them financial stability and creative freedom. These artists worked in relative privacy, experimenting with their craft.

On the flip side, the Salon Cubists, including Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay, and Léger, showcased their work at public exhibitions like the Salon d'Automne and the Salon des Indépendants in Paris. Their art aimed to explore forms, contrasting the prevalent emphasis on color in Neo-Impressionism. This group's exhibitions, especially in 1911, brought Cubism to the public eye, sparking both fascination and controversy.

In a 1911 article, The New York Times covered these avant-garde works, questioning their meaning and sanity. Names like Picasso, Matisse, and Metzinger were mentioned, captivating Paris and the world, blurring the lines between art and madness.

1.2.1 Salon des Indépendants

The 1912 Salon des Indépendants in Paris, held from March 20 to May 16, was a pivotal event marked by controversy. Marcel Duchamp's daring work, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, caused a scandal even among the Cubists. Surprisingly, it was rejected by the hanging committee, which included Duchamp's own brothers and fellow Cubists. Although displayed later at the Salon de la Section d'Or in October 1912 and the 1913 Armory Show in New York, Duchamp never forgave his brothers and colleagues for censoring his creation. Notable artworks at the Salon included Juan Gris' Portrait of Picasso, Metzinger's La Femme au Cheval (Woman with a Horse) from 1911–1912, Delaunay's monumental La Ville de Paris, and Léger's La Noce, The Wedding.

1.2.2 Galeries Dalmau

In 1912, a groundbreaking event unfolded at Galeries Dalmau: the world's first officially declared group exhibition of Cubism, titled Exposició d'Art Cubista. This exhibition, held in Barcelona from April 20 to May 10, featured bold displays by prominent artists like Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Juan Gris, Marie Laurencin, and Marcel Duchamp. Comprising 83 works from 26 artists, the Dalmau exhibition sparked both admiration and controversy.

Jacques Nayral, associated with Gleizes, penned the Preface for this Cubist showcase. The exhibition's impact was profound, attracting significant media attention before, during, and after the event. While the coverage was extensive, it wasn't universally positive. Some publications, such as Esquella de La Torratxa and El Noticiero Universal, criticized the Cubists through caricatures and disparaging remarks. Despite initial suspicions, the Dalmau exhibition marked a pivotal moment, stirring public interest and contributing significantly to the evolution of modernism in Europe.

1.2.3 Salon d'Automne

The 1912 Salon d'Automne, marked by Cubist innovations, sparked public outrage for using government-owned buildings like the Grand Palais. Jean Pierre Philippe Lampué's indignation made headlines in Le Journal on October 5, 1912. The controversy reached the Paris Municipal Council and even led to a debate in the Chambre des Députés regarding public funds supporting such art. In this charged atmosphere, Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes penned Du "Cubisme" in 1912, addressing the uproar. The exhibition featured notable works like Le Fauconnier's Les Montagnards attaqués par des ours, Joseph Csaky's Deux Femme, and abstract pieces by Kupka and Picabia.

1.2.4 Abstraction and the ready-made

In the realm of Cubism, there existed a spectrum ranging from the restrained approach of Picasso and Braque to the more radical expressions embraced by other artists like František Kupka, Delaunay, Léger, Picabia, and Duchamp. While Picasso and Braque clung to elements of recognizable objects, Kupka and the Orphists, including Delaunay, Léger, Picabia, and Duchamp, delved into total abstraction. Kupka's entries in the 1912 Salon d'Automne were profoundly abstract and metaphysical. Duchamp and Picabia ventured into expressive abstraction, exploring intricate emotional and sexual themes. Delaunay experimented with vibrant colors, blending planar structures, and deviating significantly from reality. Léger's Contrasts of Forms series, despite its abstract nature, reflected themes of modernization. Apollinaire lauded these developments in abstract Cubism as a new form of "pure" painting, yet their diversity defied easy categorization.

Marcel Duchamp, also regarded as an Orphist by Apollinaire, introduced an even more radical concept: the ready-made. Duchamp's innovation lay in presenting ordinary objects, detached from their utilitarian context, as self-contained artworks. For instance, he affixed a bicycle wheel to a kitchen stool in 1913 and in 1914, chose a bottle-drying rack as a sculpture in its own right. This marked a significant departure from traditional artistic norms, redefining the very essence of art itself.

1.2.5 Section d'Or

The Section d'Or, or the Groupe de Puteaux, emerged as a vital collective of artists during the early 20th century, between 1911 and 1914. This group, consisting of painters, sculptors, and critics, was deeply entrenched in the realms of Cubism and Orphism. Their significant presence was felt after a controversial display at the 1911 Salon des Indépendants, but it was their exhibition at the Galerie La Boétie in Paris in October 1912 that truly marked a watershed moment for Cubism before World War I.

During this influential exhibition, over 200 artworks were showcased. What made this event especially captivating was that many artists exhibited pieces that represented their evolution from 1909 to 1912, giving the exhibition the aura of a Cubist retrospective. The group adopted the name Section d'Or to distinguish themselves from the narrower definition of Cubism that was concurrently being developed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in the Montmartre quarter of Paris. This naming choice was also significant in underlining that Cubism was not an isolated art form but rather a continuation of a rich artistic tradition. Interestingly, the name also alluded to the golden ratio, a concept that had fascinated intellectuals for centuries.

The concept of the Section d'Or was conceived through discussions among influential Cubist figures like Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, and Jacques Villon. The title itself was suggested by Villon, inspired by a 1910 translation of Leonardo da Vinci's Trattato della Pittura by Joséphin Péladan.

At this juncture, European artists were being profoundly influenced by non-Western art forms, such as African, Polynesian, Micronesian, and Native American art. Visionaries like Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso found inspiration in the simplicity and raw power of these foreign cultures’ styles. Picasso, in particular, was deeply influenced by Iberian sculpture, African art, and tribal masks. His 1907 masterpiece, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, often cited as a protocubist work, showcased a marked departure from traditional art, paving the way for what would become Cubism.

This period of artistic evolution saw a radical shift in the way artists perceived and portrayed their subjects. Cézanne's influence was critical, particularly in his emphasis on multifaceted areas of paint and the simplification of natural forms into geometric shapes. The Cubists took these concepts further, representing all surfaces of objects within a single picture plane. This revolutionary approach transformed the visualization of objects in art, laying the foundation for what we now recognize as Cubism.

The historical study of Cubism commenced in the late 1920s, drawing primarily from the insights of Guillaume Apollinaire. However, the widely accepted terms "analytical" and "synthetic" Cubism, which were coined in the mid-1930s, were retrospective impositions. These labels, although widely used, do not fully encapsulate the complexities of Cubism during its formative years.

The term "Cubism" itself saw varied usage before becoming mainstream. Notably, in 1906, critic Louis Chassevent used the term "cube" in reference to artists like Jean Metzinger and Robert Delaunay. The critical use of the word “cube” can even be traced back to 1901, indicating a much earlier association with the concept. However, it was not until 1911 that the term came into general usage, particularly concerning artists like Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay, and Léger.

To counter the confusion surrounding Cubism, especially after the public scandal following the 1911 Salon des Indépendants and the 1912 Salon d'Automne in Paris, Metzinger and Gleizes authored and published "Du 'Cubisme'" in 1912. This theoretical treatise clarified their aims as artists and laid the groundwork for Cubist philosophy. The concept of observing a subject from multiple points in space and time simultaneously, fusing these perspectives into a single image, became a hallmark of Cubism.

The Section d'Or's profound impact on the art world was undeniable. Through their exhibitions and writings, they not only defined Cubism but also made it accessible to a wider audience, solidifying its status as a significant avant-garde movement. The Section d'Or's legacy continues to influence artists and art enthusiasts, reminding us of the enduring power of their innovative artistic vision.

1.3 Crystal Cubism (1914-1918)

Between 1914 and 1916, Cubism underwent a significant transformation characterized by a shift towards emphasizing large overlapping geometric planes and flat surfaces. This change in style, particularly prominent from 1917 to 1920, was adopted by several artists, notably those affiliated with the art dealer Léonce Rosenberg. This evolution, marked by tighter compositions and a clear sense of order, earned the name 'crystal' Cubism, as coined by critic Maurice Raynal. The earlier Cubist themes related to the fourth dimension, modern dynamism, the occult, and Henri Bergson's concept of duration were replaced by a purely formal approach.

Crystal Cubism, along with its associated return to order (rappel à l'ordre), was seen as a response to the desire to escape the harsh realities of World War I, both for those serving in the military and civilians. This purification of Cubism, lasting from 1914 to the mid-1920s, with its unified and disciplined approach, mirrored a broader ideological shift towards conservatism in French society and culture.

1.4 Cubism post 1918

The revolutionary era of Cubism primarily occurred before 1914, yet after World War I, thanks to the support of dealer Léonce Rosenberg, it regained prominence in the art world. Artists like Picasso, Braque, Gris, and Metzinger, although exploring diverse styles, periodically returned to Cubism even after 1925. While Cubism faced challenges from geometric abstraction and Surrealism in the mid-1920s, it experienced a resurgence in the 1920s and 1930s through artists like Stuart Davis and Ben Nicholson. In France, Cubism faced a decline post-1925, but exhibitions and theoretical writings kept its spirit alive. The movement, evolving within individual artists' works and diverse styles, remained a benchmark for artistic innovation, embracing both tradition and modernity.

3. Cubism - Intentions and Criticism

The Cubism of Picasso and Braque held profound philosophical and artistic significance. Salon Cubists, including Metzinger and Gleizes, explored diverse Cubist styles, not merely derivative of Picasso and Braque. In Du "Cubisme," Metzinger and Gleizes connected time to multiple perspectives, reflecting Henri Bergson's concept of 'duration,' where past, present, and future merge subjectively. The Salon Cubists used faceting and multiple viewpoints to convey the fluidity of consciousness, challenging traditional linear perspective. Their innovative concept of simultaneity blurred spatial and temporal dimensions, showcased in iconic works like Metzinger's Nu à la cheminée and Gleizes' Le Dépiquage des Moissons. This complex technique was also evident in Léger's The Wedding, aligning Salon Cubism with early Futurist art. These revolutionary ideas influenced American art when showcased at the 1913 Armory Show in New York, marking a pivotal moment in the history of modern art.

4. Cubism - The Artists

4.1 Jean Metzinger

Jean Metzinger, a pioneering Cubist artist, played a pivotal role in reshaping the art world during the early 20th century. His innovative approach to painting, characterized by intricate geometric forms and simultaneous perspectives, challenged traditional artistic norms. Metzinger's contributions, exemplified in iconic works like "Nu à la cheminée," continue to influence modern art, leaving a lasting legacy.

4.2 Georges Braque

Georges Braque, a pioneering Cubist artist, co-founded the Cubist movement with Picasso. His innovative approach fragmented objects into geometric shapes, pioneering a new visual language. Braque's work focused on deconstructing reality, emphasizing multiple viewpoints and geometric forms. His contributions to Cubism revolutionized art, leaving an enduring impact on modern artistic expression.

4.3 Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso, the pioneering Cubist artist, revolutionized the art world with his innovative approach. Co-founder of Cubism with Georges Braque, Picasso broke traditional forms, depicting subjects from multiple viewpoints simultaneously. His fragmented, geometric style transformed how artists perceived space and representation, leaving an indelible mark on modern art.

4.4 Albert Gleizes

Albert Gleizes, a pioneering Cubist artist, was a key figure in the early 20th-century avant-garde art movement. Alongside Jean Metzinger, he co-authored the influential Cubist manifesto "Du "Cubisme"." Gleizes developed a distinctive style marked by geometric forms, vibrant colors, and intricate compositions, challenging traditional artistic perspectives. His innovative work significantly shaped the Cubist movement and modern art.

4.5 Robert Delaunay

Robert Delaunay (1885-1941) was a pioneering Cubist artist known for his vibrant use of color and innovative geometric forms. Alongside his wife Sonia, he explored the concept of simultaneous contrasts and the interaction of colors. Delaunay's work, marked by dynamic compositions and a unique blend of Cubism and abstraction, significantly influenced modern art.

4.6 Fernand Léger

Fernand Léger, a prominent Cubist artist, revolutionized modern art with his distinctive style characterized by bold geometric shapes, mechanical forms, and vibrant colors. His works, including paintings, sculptures, and films, showcased a dynamic fusion of Cubism and abstraction, depicting the energy and rhythm of modern urban life. Léger's innovative approach left an enduring impact on 20th-century art.

4.7 Juan Gris

Juan Gris, a prominent Cubist artist, was a master of geometric abstraction. Born in 1887, he became a key figure in the Cubist movement alongside Picasso and Braque. Gris' unique style featured precise shapes, vibrant colors, and meticulous compositions, reflecting a harmonious balance between abstraction and reality. His innovative work continues to influence modern art.

4.8 Henri Le Fauconnier

Henri Le Fauconnier, a pioneering Cubist artist, played a vital role in the early 20th-century art movement. Known for his distinctive geometric style and bold use of color, Le Fauconnier's work, such as "Abundance" and "The Huntsman," exemplified the Cubist approach, influencing the trajectory of modern art. His innovative vision continues to inspire artists today.

5. Cubism - FAQ's

-

What is Cubism?

- Cubism is an early 20th-century art movement that revolutionized traditional artistic perspectives. It emphasizes geometric shapes, abstract forms, and multiple viewpoints to represent subjects.

-

Who were the pioneers of Cubism?

- Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque are credited as the founders of Cubism. They developed the movement in the early 1900s in Paris.

-

What are the key characteristics of Cubist art?

- Cubist artworks feature fragmented forms, geometric shapes, and a deconstruction of traditional perspective. Artists often use a combination of flat and angular surfaces to depict objects and scenes.

-

Why is Cubism considered revolutionary?

- Cubism challenged traditional artistic techniques by breaking down objects into basic shapes and reassembling them. This approach revolutionized how artists perceived and represented the world.

-

How did Cubism influence other art forms?

- Cubism had a significant impact on various art forms, including sculpture, literature, and architecture. It inspired new ways of thinking about space, form, and artistic expression.

-

What are the different phases of Cubism?

- Cubism can be divided into several phases, including Analytical Cubism (early phase emphasizing fragmented forms) and Synthetic Cubism (later phase incorporating collage elements).

-

Who were the notable artists associated with Cubism?

- Apart from Picasso and Braque, prominent Cubist artists include Juan Gris, Fernand Léger, and Robert Delaunay, each contributing unique styles to the movement.

-

How did Cubism influence the art world globally?

- Cubism's influence spread internationally, shaping modern art movements in Europe, the Americas, and beyond. Artists worldwide adopted Cubist principles, leading to diverse interpretations and innovations.

-

Is Cubism still relevant in contemporary art?

- Yes, Cubism continues to inspire contemporary artists. Its emphasis on abstraction, geometry, and innovative perspectives remains influential in the evolving landscape of modern art.

-

Where can I see famous Cubist artworks?

- Major museums and galleries worldwide, such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, house iconic Cubist masterpieces. Visiting these institutions provides a rich experience of Cubist art.

6. Cubism - Related Articles

6.1 Pablo Picasso

6.2 Georges Braque

6.3 Jean Metzinger

6.4 Albert Gleizes

6.5 Juan Gris

6.6 Fernand Léger

6.7 Robert Delaunay