Table of Contents:[hide]

1. Jean Metzinger: The Mastermind Behind Cubism

Jean Dominique Antony Metzinger, a luminary of 20th-century French art, left an indelible mark on the world through his multifaceted talents as a painter, theorist, writer, critic, and poet. Alongside Albert Gleizes, he penned the inaugural theoretical work on Cubism, a movement that reshaped the art landscape.

Metzinger's journey commenced in the vibrant hues of neo-Impressionism, drawing influence from luminaries like Georges Seurat and Henri-Edmond Cross. Transitioning through Divisionism and Fauvism, he embraced Cubism in 1908, becoming both a trailblazing artist and a pioneering theorist. His groundbreaking work, "Note sur la Peinture," published in 1910, introduced the concept of multiple viewpoints, shattering traditional artistic confines.

At the epicenter of Cubism's emergence, Metzinger's artistic and intellectual prowess illuminated the movement. His role as a mediator between the Bateau-Lavoir group and the Section d'Or Cubists solidified his centrality. Amidst World War I, he co-founded Crystal Cubism, infusing mathematics into art, leading to the influential treatise "La Peinture et ses lois" by Albert Gleizes.

Metzinger's vision transcended classical boundaries, embracing dynamic perspectives and diverse viewpoints. His impact extended to quantum mechanics, inspiring visionaries like Niels Bohr. His legacy, epitomized by masterpieces like "La Femme au Cheval," echoes through the annals of art history, immortalizing him as a pioneer of Cubism and a maestro of artistic innovation.

2. Jean Metzinger Paintings - Video

3. Early Life of Jean Metzinger: From Military Roots to Artistic Awakening

Jean Metzinger, a prominent figure in the Cubist movement, hailed from a distinguished military family. His lineage boasted Nicolas Metzinger, a Captain in Napoleon Bonaparte's 1st Horse Artillery Regiment. Despite this heritage, Jean's interests leaned towards mathematics, music, and painting.

Following his father's early demise, Metzinger's mother, Eugénie Louise Argoud, envisioned a medical career for him. However, Jean's passion for art prevailed. Under the tutelage of portrait painter Hippolyte Touront, he explored the vibrant Parisian art scene.

Metzinger's artistic journey began with three paintings displayed at the Salon des Indépendants in 1903. These works funded his move to Paris, where, at just 20, he established himself as a professional painter. His association with renowned artists like Raoul Dufy and Pablo Picasso marked his rapid ascent.

Berthe Weill's gallery became a significant platform for Metzinger's art, where he exhibited alongside luminaries like Matisse and Derain. His meeting with Albert Gleizes in 1906 catalyzed his Cubist exploration, and by 1908, he exhibited with prominent Cubists like Braque and Picasso.

The years 1908-1909 saw Metzinger's inclusion in influential exhibitions, shaping his trajectory in the avant-garde art scene. Additionally, he tied the knot with Lucie Soubiron in 1909, marking a personal milestone amidst his burgeoning artistic career. These formative years set the stage for Metzinger's transformative journey within the realm of modern art.

4. Neo-Impressionism and Divisionism: Metzinger's Mosaic Revolution

In the early 20th century, Jean Metzinger embraced the Neo-Impressionist movement led by Henri-Edmond Cross. By 1903, he was deeply involved in this revival, experimenting with larger brushstrokes and vibrant hues. Influenced by Seurat and Cross, Metzinger introduced a new geometric dimension into his art, liberating himself from the constraints of traditional nature-inspired paintings.

During 1905-1910, Metzinger, along with artists like Derain, Delaunay, and Matisse, reinvigorated Neo-Impressionism in an altered form. His mosaic-like Divisionist technique, characterized by intricate squares of color, marked a departure from naturalism. Metzinger's innovative approach, akin to a poetic interpretation of color, captured the essence of emotions evoked by nature.

His art, akin to literary expression, created decorative harmonies and symphonies of color, reflecting deep sentiments rather than replicating reality. Metzinger's revolutionary technique resonated not just in his contemporaneous works but also laid the groundwork for the Cubist movement, influencing artists like Piet Mondrian and the Futurists. This transformative period marked the genesis of Metzinger's iconic style, setting the stage for his significant contributions to the art world.

5. Cubism: Metzinger's Evolution of Form

In the vibrant art scene of early 20th-century Paris, avant-garde artists like Jean Metzinger found inspiration in the revolutionary work of Paul Cézanne. The retrospective exhibitions of Cézanne's paintings in the years leading up to 1907 stirred something profound in the creative minds of the era. For Metzinger, Cézanne's influence served as a catalyst, guiding his artistic transformation from Divisionism to Cubism.

By 1908, Metzinger was experimenting with fracturing forms, exploring complex multiple views of the same subject. His artistry didn't merely reflect reality; it deconstructed it. Critics noted the abstraction in his works, leading to an analytical Cubist style by early 1910.

Metzinger was part of a pivotal group alongside Georges Braque, Fernand Léger, and Robert Delaunay, among others. In their shared studio sessions, they delved deep into form, challenging the conventional perspectives of the time. This collective spirit birthed Cubism, with Metzinger playing a vital role.

In 1911, Metzinger and his peers exhibited together, provoking both awe and controversy. They broke away from traditional depictions, reducing human figures to pallid cubes, a departure that marked the birth of Cubism as a recognized movement. This transformative period saw the publication of "Du 'Cubisme'" by Metzinger and Albert Gleizes, the pioneering treatise that laid the theoretical foundation for Cubism. This publication garnered widespread attention, marking Cubism's formal introduction to the world.

Metzinger's unique approach, characterized by a meticulous balance between form and abstraction, didn't just revolutionize art; it inspired a philosophical shift in the way artists approached their craft. His mastery of form and the depth of his intellectual exploration continue to resonate in the annals of art history, shaping the trajectory of modern artistic expression.

6. Crystal Cubism: Metzinger's Artistic Revolution

In the dynamic realm of early 20th-century art, Jean Metzinger embarked on a groundbreaking journey that would redefine artistic conventions and pave the way for a new era in Cubism. Metzinger's evolution towards synthesis in 1914–15 marked a turning point, characterized by the configuration of flat squares, trapezoidal and rectangular planes that interweaved and overlapped—a new perspective aligned with the "laws of displacement."

This transformative period birthed iconic works such as 'Le Fumeur' and 'Au Vélodrome,' where Metzinger ingeniously filled simple shapes with intricate gradations of color and rhythmic curves. These artistic explorations culminated in masterpieces like 'Soldier at a Game of Chess' and 'L'infirmière (The Nurse).'

The term 'Crystal Cubism,' although later coined by Maurice Raynal, encapsulates this period aptly. It represented more than just a style; it embodied a philosophy. Metzinger's Crystal Cubism was a return to simplicity, embracing a robust, pared-down artistry. Techniques were streamlined, chiaroscuro tricks were abandoned, and the artifices of the palette were left behind.

Metzinger's departure from traditional Cubism circa 1918 didn't signify a renunciation but rather a profound transformation. He returned to nature, seeking a harmonious union between the pictorial and the natural. His landscapes, showcased in his 1921 exhibition, displayed a rhythm and perspective that subtly merged the abstract with the tangible.

Despite the apparent departure, Metzinger's unique style persisted. His careful positioning of form, color, and his delicate assimilation of figures and backgrounds persisted. In his paintings, one could discern subtle profiles emerging from divided features, a testament to his mastery of perspective and the fourth dimension.

Jean Metzinger's role in the Cubist movement was multifaceted. He was not merely an artist; he was a theorist and a mediator. His balance between intellectuality and visual spectacle placed him at the heart of Cubism. His legacy continues to influence artists, reminding the world that Cubism was not just an art movement; it was a transformative philosophy that transcended traditional boundaries, and Metzinger was at its forefront, shaping its narrative and evolution.

7. Decoding Cubism: Metzinger's Visionary Theories

In the early 20th century, the art world witnessed a seismic shift, led by visionaries like Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes. Their 1912 manifesto, Du "Cubisme", was a pivotal moment, challenging traditional artistic norms and introducing a revolutionary perspective that would reshape the way we perceive reality.

7.1 Non-Euclidean Geometry: Beyond Boundaries

At the core of Du "Cubisme" was the exploration of non-Euclidean geometry. Unlike classical, or Euclidean geometry, non-Euclidean geometry delved deeper into space, incorporating the fourth dimension into the three-dimensional canvas. Cubism, Metzinger argued, was not just a departure from classical methods; it was an embrace of a richer, multidimensional understanding of space and time.

7.2 The Fusion of Past and Present

Metzinger's approach to Cubism was a fusion of the past and the present. He believed in embracing tradition, understanding that it was an inherent part of the artist's essence. His admiration for artists like Ingres and Seurat was evident, and he saw the artist's challenge as a harmonious integration of the past, the present, and the future. This delicate balance between the transient and the eternal fascinated Metzinger, leading to an artistic equilibrium that was both innovative and rooted in artistic heritage.

7.3 The Concept of Mobile Perspective

One of the revolutionary ideas introduced by Metzinger was "mobile perspective." Traditional art was limited to a single viewpoint, but Metzinger envisioned capturing objects from multiple angles simultaneously. This concept, detailed in his article Note sur la Peinture, liberated artists from the confines of a singular perspective. The notion of moving around objects and representing them from various viewpoints was a shock to the public initially, but it eventually became an accepted and celebrated aspect of Cubism.

7.4 Cubism's Sensational Revolution

Du "Cubisme" challenged the very essence of art. Metzinger and Gleizes argued that art should be experienced through sensations alone. Traditional paintings, they believed, offered a limited, motionless view of the world. In contrast, Cubism, with its dynamic geometric structures, represented the evolving continuum of human experiences. The artists viewed the world from a multitude of angles, capturing the ever-changing nature of reality. Cubism, to them, was not just an art movement; it was a profound understanding of our senses and a representation of life's continuous evolution.

In essence, Metzinger's theories propelled Cubism beyond the realms of mere representation. They turned art into a sensory experience, a profound exploration of the human condition, and a celebration of the dynamic, multidimensional world we inhabit. Through his visionary ideas, Metzinger revolutionized art, leaving an indelible mark on the artistic landscape for generations to come.

8. Decoding Cubism's Scientific Roots: The Vision of Jean Metzinger

The world of art underwent a profound transformation in the early 20th century, marked by the rise of Cubism, a movement spearheaded by visionaries like Jean Metzinger. Yet, what's often overlooked is the deep connection between Cubism and the scientific advancements of the time. In particular, Metzinger's exploration of Cubism was deeply influenced by mathematical concepts, leading to a revolutionary artistic approach that would leave a lasting impact on the art world.

8.1 Cubism and Non-Euclidean Mathematics

In their groundbreaking manifesto, Du "Cubisme", Metzinger and Albert Gleizes delved into the theoretical aspects of Cubism. They made explicit references to non-Euclidean geometry, especially Riemann's theorems, to explain the spatial dynamics of Cubist paintings. The Cubists, including Metzinger, were intrigued by the idea of observing subjects from various points in space and time simultaneously. This concept, known as "mobile perspective," wasn't directly borrowed from Einstein's theory of relativity but shared a similar intellectual atmosphere, influenced by the works of Jules Henri Poincaré.

8.2 The Influence of Poincaré and "Mobile Perspective"

Poincaré, a renowned French mathematician and physicist, made significant contributions to celestial mechanics, quantum theory, and the theory of relativity. His ideas on the relativity of simultaneity and the incorporation of time with spatial dimensions resonated with the Cubists' notion of mobile perspective. Metzinger and Gleizes, in particular, explored this concept, allowing them to represent objects from multiple viewpoints simultaneously.

8.3 The Role of Maurice Princet

Maurice Princet, often dubbed "the mathematician of Cubism," played a crucial role in bridging mathematics and art. He introduced artists like Picasso, Apollinaire, and Metzinger to the concept of the fourth spatial dimension and non-Euclidean geometry. Metzinger, with his mathematical background, found a kindred spirit in Princet, who shared his passion for exploring the multidimensional aspects of reality.

8.4 Cubism: A Fusion of Mathematics and Art

Metzinger's early interest in mathematics and his exposure to Poincaré's ideas deeply influenced his approach to Cubism. For him, Cubism wasn't merely an artistic movement but a profound exploration of human sensation and intelligence. By integrating mathematical principles and intellectual depth into their art, Metzinger and his contemporaries elevated Cubism beyond traditional representation, creating a new visual language that resonated with the dynamic realities of the world.

In essence, Metzinger's Cubism was more than just a style—it was a testament to the symbiotic relationship between science and art. His paintings became intricate mathematical compositions, exploring the fundamental nature of reality and perception. Through his visionary approach, Metzinger paved the way for future generations of artists, demonstrating the transformative power of merging scientific knowledge with artistic expression.

9. The Artistic Roots of Quantum Mechanics: Jean Metzinger's Influence

The intersection of art and science has often been a realm of profound inspiration, where creativity in one domain sparks groundbreaking revelations in another. In the case of quantum mechanics, a field that has reshaped our understanding of reality, the influence of Cubism, particularly the works of artist Jean Metzinger, played a pivotal role in shaping the revolutionary principles of this scientific discipline.

9.1 Cubism: Shaping Perspectives

Cubism, epitomized by the groundbreaking theories of Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes in their seminal work Du "Cubisme", redefined artistic representation. The core idea of Cubism was to portray scenes from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, a concept known as 'mobile perspective.' Artists aimed to represent the totality of an object by combining various perspectives on a single canvas. This departure from classical perspectives and surface transitions forced artists to reconsider the role of the observer, transforming the act of observation into a dynamic, interactive process.

9.2 Niels Bohr: Bridging Art and Quantum Theory

Niels Bohr, a luminary in the realm of quantum mechanics, found inspiration in Cubism, particularly in the writings of Jean Metzinger. Bohr's office housed an iconic Metzinger painting, La Femme au Cheval (Woman with a Horse), a striking example of mobile perspective implementation. Guided by the principles of Cubism, Bohr envisioned quantum particles as entities existing both as particles and waves simultaneously. This duality, a fundamental tenet of quantum mechanics, echoed the essence of Cubism – the ability to portray an object from diverse viewpoints, all equally valid yet contextually specific.

9.3 The Epistemological Shift: From Art to Science

In the philosophical words of Bohr, the elucidation of an object necessitates diverse viewpoints, defying a singular description. This epistemological shift mirrored Cubism's approach, where objects had multiple forms, contingent upon the observer's perception. Metzinger's 'total image,' a culmination of successive viewpoints, echoed Bohr's notion of diverse perspectives shaping our understanding of reality. Just as the artist's choices influenced the painting's outcome, an observer's perception influenced the quantum particle's behavior.

9.4 The Fusion of Art and Science

The amalgamation of Cubism's revolutionary artistry and Bohr's quantum mechanics led to a profound realization: both realms depended on perspectives and choices. Metzinger's theories challenged traditional artistic norms, embracing the multiplicity of reality. Simultaneously, Bohr's quantum mechanics shattered classical determinism, acknowledging the role of observation in shaping outcomes.

In essence, the creative interplay between art and science, exemplified by the symbiotic relationship between Metzinger's Cubism and Bohr's quantum mechanics, underscores the power of diverse perspectives. Through the lens of Cubism, quantum mechanics found a profound metaphor – a testament to the interconnectedness of artistic expression and scientific understanding, forever altering the way we perceive both the canvas and the cosmos.

10. Jean Metzinger: Evolution of Artistry and Legacy

Jean Metzinger, a trailblazing artist whose innovative approach to Cubism and subsequent exploration of various artistic styles left an indelible mark on the art world. Beyond his creative endeavors, Metzinger's impact resonated through exhibitions, teaching, and the legacy he left behind.

10.1 Partnership with Léonce Rosenberg: A Turning Point

In 1916, Metzinger inked a groundbreaking deal with the esteemed art dealer Léonce Rosenberg. This three-year contract, later extended to 15 years, gave Rosenberg exclusive exhibition and sales rights to Metzinger's works. The collaboration not only solidified Metzinger's reputation but also laid the foundation for his artistic journey.

10.2 Artistic Evolution: From Cubism to Realism and Beyond

Metzinger's artistic odyssey led him from the realms of Cubism to realism, where he masterfully blended elements of his Cubist style. Between 1924 and 1930, he embraced a 'mechanical world' akin to Fernand Léger's vision. Yet, even as his style evolved, Metzinger retained his unique artistic identity. His creations, rich in metaphoric imagery, delved into urban life, still-life subjects, and the nuances of science and technology. This period also saw his romantic involvement with Suzanne Phocas, culminating in marriage in 1929.

10.3 Teaching and Exhibitions: Shaping Future Generations

Metzinger's influence extended to the realm of education. He imparted his artistic wisdom at esteemed institutions like the Académie de La Palette, Académie Arenius, and Académie de la Grande Chaumière. His students included luminaries like Serge Charchoune, Jessica Dismorr, and Nadezhda Udaltsova, among others. Metzinger's dedication to teaching cultivated a new generation of artists, leaving an enduring impact on the art community.

11. Exhibition Legacy: From Paris to International Recognition

Metzinger's artistic prowess found global acclaim through a series of exhibitions. His works graced prestigious galleries in Paris, New York, London, and Chicago, captivating audiences and critics alike. His solo exhibitions, notably at Léonce Rosenberg's Galerie de L'Effort Moderne, Leicester Galleries in London, and the Arts Club of Chicago, showcased his artistic brilliance.

12. Metzinger's Enduring Legacy: The Intersection of Art and Theory

14. List of Jean Metzinger Paintings

with dates and current locations

- Rose Flower in a Vase, 1902

- The Clearing (Clairière), c. 1903

- Landscape (Paysage), 1904, Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina

- The Low Tide (La Marée Basse), c. 1904

- Le Chemin a travers les champs, c. 1904

- The Sea Shore, Bord de mer (Le Mur Rose), 1904–05, Indianapolis Museum of Art

- La Tour de Batz au coucher du soleil, 1904–05

- Le Château de Clisson, 1904–05, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes

- Jeune Fille au Fauteuil (Femme nue au chignon assise), 1905

- Neo-Impressionist Landscape (Paysage Neo-Impressionniste), 1905, Musée d'art moderne de Troyes

- Two Nudes in a Garden (Deux nus dans un jardin), 1905–06, University of Iowa Museum of Art

- Two Nudes in an Exotic Landscape (Baigneuses: Deux nus dans un jardin exotique), 1905–06, Carmen Cervera Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection

- Coucher de Soleil No. 1 (Landscape), c. 1906, Kröller-Müller Museum

- La danse (Bacchante), c. 1906, Kröller-Müller Museum

- Parc Montsouris, Morning (Matin au Parc Montsouris), 1906

- Nude (Nu), 1906, Norton Museum of Art

- Paysage coloré aux oiseaux exotiques, 1906, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

- Portrait of Delaunay (Portrait de Delaunay), 1906

- Woman with a Hat (Femme au Chapeau), 1906, Korban Art Foundation

- Tropical Landscape (Paysage Tropical), 1906–07

- Paysage coloré aux oiseaux aquatiques, 1907

- Bathers (Baigneuses), c. 1908

- Nude (Nu à la cheminée), 1910

- Portrait of Apollinaire (Portrait d'Apollinaire), 1910

- Two Nudes (Deux nus), 1910–11, Gothenburg Museum of Art

- Standing Nude (Nu debout), 1910–11, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

- Portrait of Madame Metzinger, 1911, Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Le goûter (Tea Time), 1911, Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Man with a Pipe (Portrait of an American Smoker), 1911–12

- Woman with a horse (La Femme au Cheval), 1911–12, Statens Museum for Kunst

- Sailboats (Scène du port), c. 1912, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art

- Landscape (Paysage), 1912, Art Institute of Chicago

- Portrait, 1912, Fogg Museum, Harvard University

- Landscape, Marine (Composition Cubiste), 1912, Fogg Museum, Harvard University

- Dancer in a café (Danseuse au café), 1912, Albright-Knox Art Gallery

- Femme à l'Éventail (Woman with a Fan), 1912, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

- La Plume Jaune (The Yellow Feather), 1912

- At the Cycle-Race Track (Au Vélodrome, Le cycliste), 1912, Peggy Guggenheim Collection

- The Bathers (Les Baigneuses), 1912–13, Philadelphia Museum of Art

- The Blue Bird (L'Oiseau bleu), 1913, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

- Portrait of Madame Metzinger, 1913, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- En Canot, Femme au Canot et à l'Ombrelle (Im Boot), 1913, Missing or destroyed

- Woman with a Fan (Femme à l'Éventail), 1913, Art Institute of Chicago

- Study for The Smoker (La fumeuse), 1913–14, Museum of Modern Art

- Soldier at a Game of Chess (Soldat jouant aux échecs), 1914–15, Smart Museum of Art

- Femme à la dentelle, 1916, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

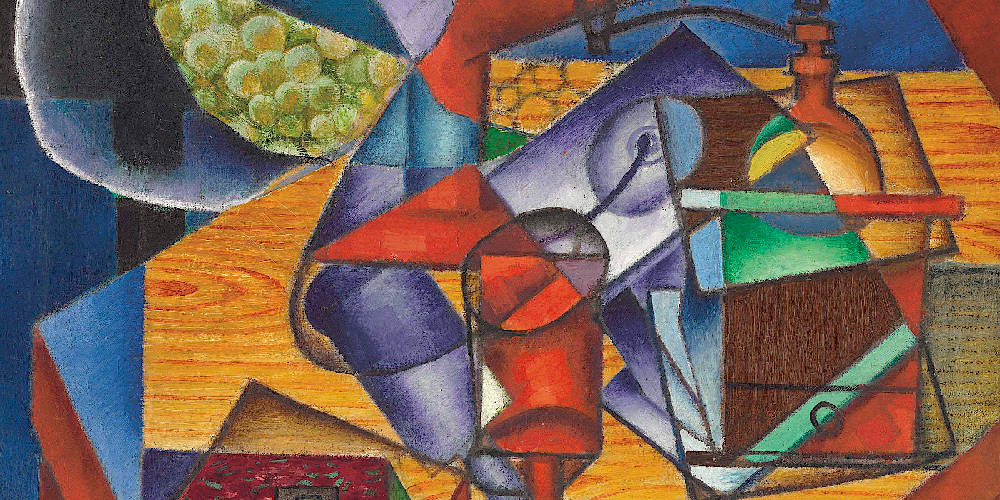

- Fruit and a Jug on a Table, 1916, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Table by a window, 1917, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Still Life, 1918, Art Institute of Chicago

- Femme face et profil (Femme au verre), 1919, Musee National d'Art Moderne, Paris

- Woman with a Coffee Pot (La Femme à la cafetière), 1919, Tate Gallery

- Still Life (Nature morte), 1919, Bilbao Fine Arts Museum

- La Tricoteuse, 1919, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

- City Landscape, 1919–20, University of Iowa Museum of Art

- Still Life (Nature morte), 1921, Minneapolis Institute of Arts

- Le Bal masque (Carnaval a Venise), 1922

- Embarkation of Harlequin (Arlequin), 1922–23

- Le Bal masqué, La Comédie Italienne, 1924

- Young woman with a guitar (Femme à la guitare), 1924, Kröller-Müller Museum

- Salome, 1924, private collection

- Equestrienne, 1924, Kröller-Müller Museum

- Composition allegorique, 1928–29, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

- Nautical still life, 1930, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

- Globe and Banjo, 1930, Art Institute of Chicago

- Nu au Soleil, 1935, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

- The Bather, Nude (La Baigneuse, Nu), 1936–37

- Yachting, 1937

- Reclining Nude (Nu allongé), 1945–50

- The Green Dress (La robe verte), c. 1950, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris