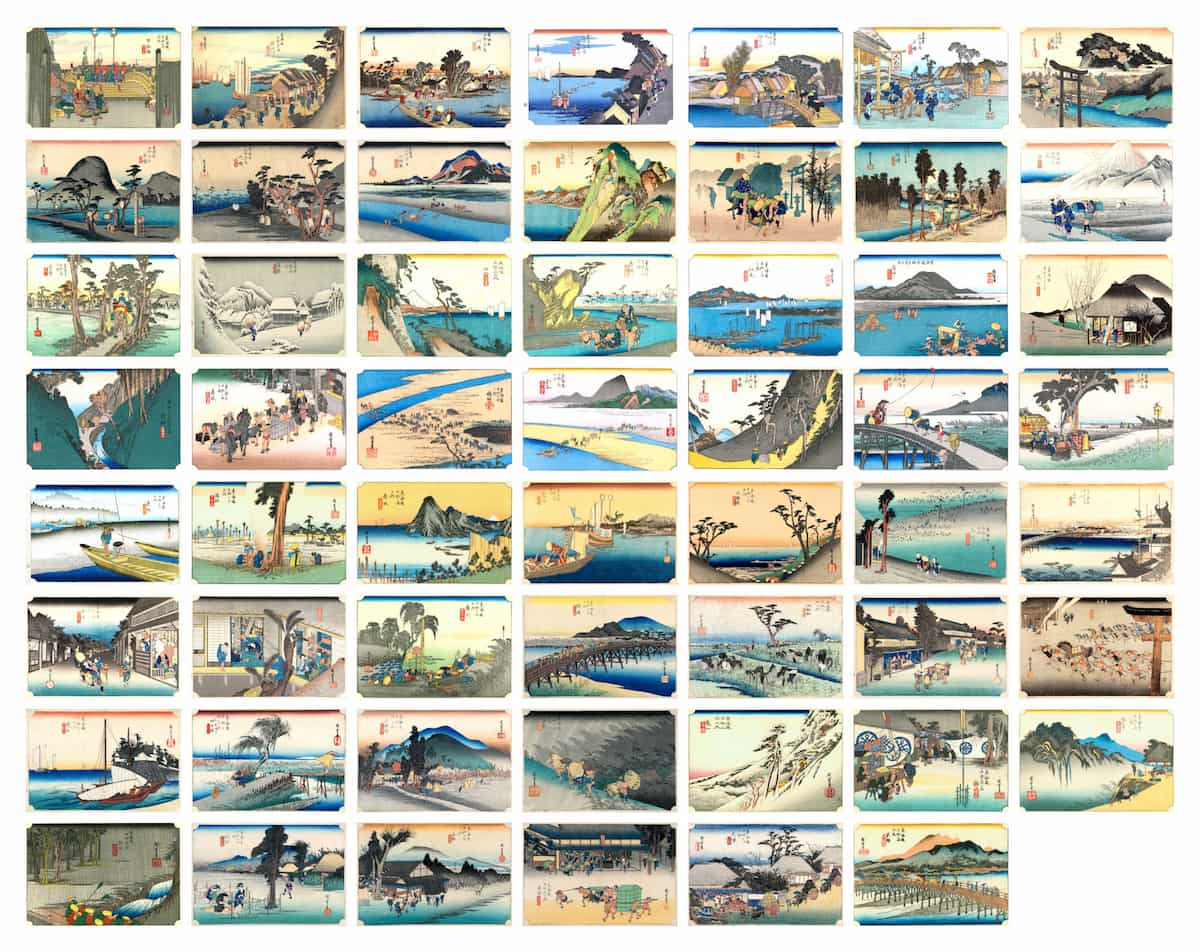

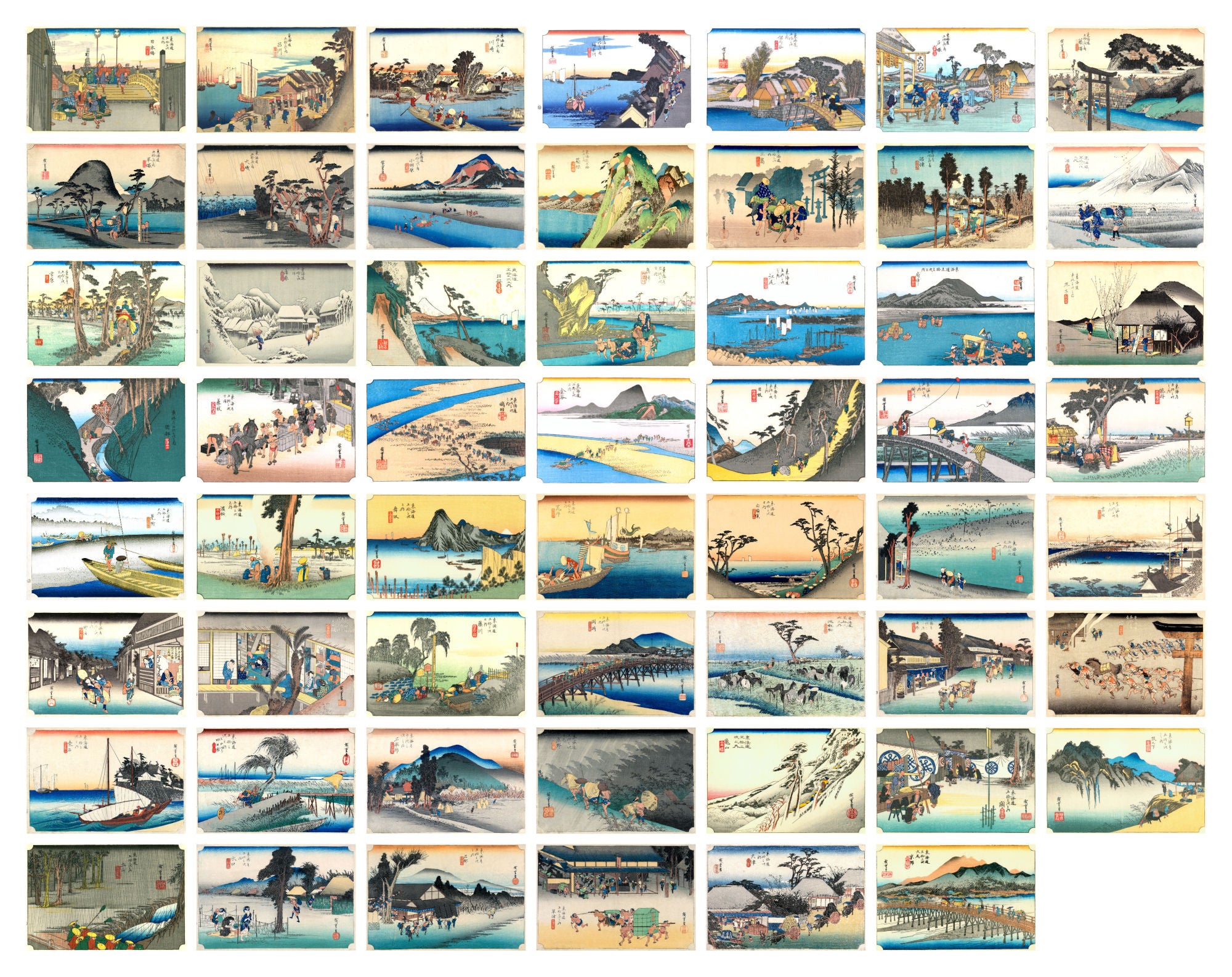

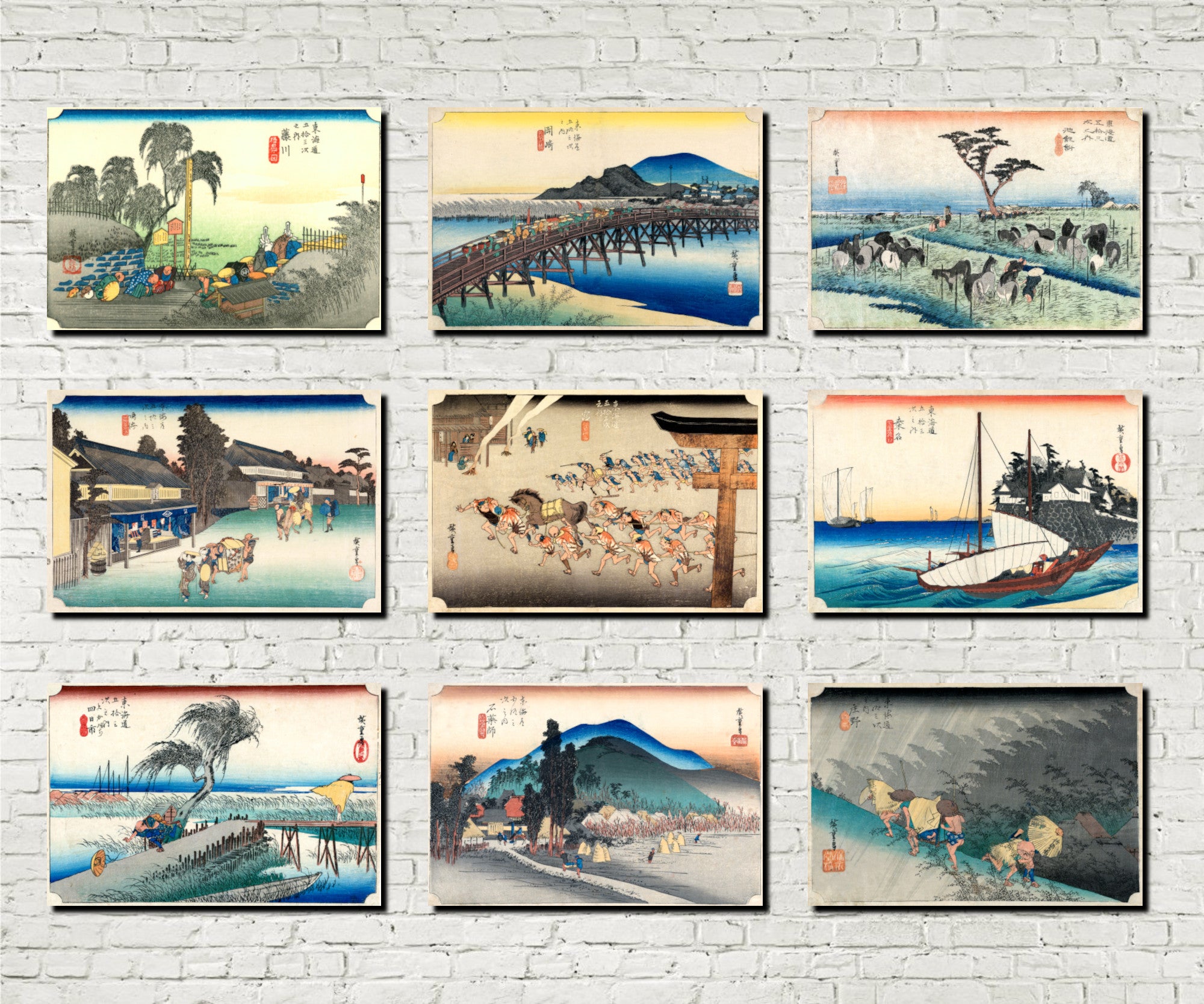

53 Stations of the Tokaido - Complete set

History of the 53 Stations of the Tokaido

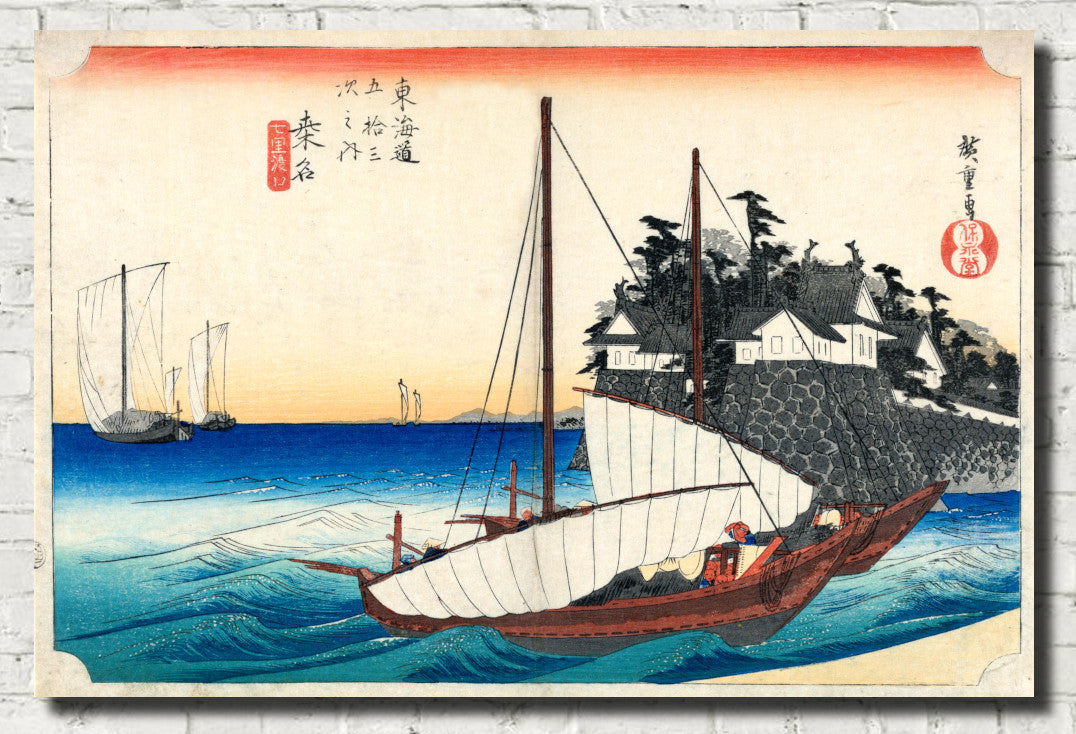

The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō (東海道五十三次, Tōkaidō Gojūsan-tsugi), in the Hōeidō edition (1833–1834), is a series of ukiyo-e woodcut prints created by Utagawa Hiroshige after his first travel along the Tōkaidō in 1832. The Tōkaidō road, linking the shōgun's capital, Edo, to the imperial one, Kyōto, was the main travel and transport artery of old Japan. It is also the most important of the "Five Roads" (Gokaidō)—the five major roads of Japan created or developed during the Edo period to further strengthen the control of the central shogunate administration over the whole country. Even though the Hōeidō edition is by far the best known, The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō was such a popular subject that it led Hiroshige to create some 30 different series of woodcut prints on it, all very different one from the other by their size (ōban or chuban), their designs or even their number (some series include just a few prints). The Hōeidō edition of the Tōkaidō is Hiroshige's best known work, and the best sold ever ukiyo-e Japanese prints. Coming just after Hokusai's Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series, it established this new major theme of ukiyo-e, the landscape print, or fūkei-ga, with a special focus on "famous views".

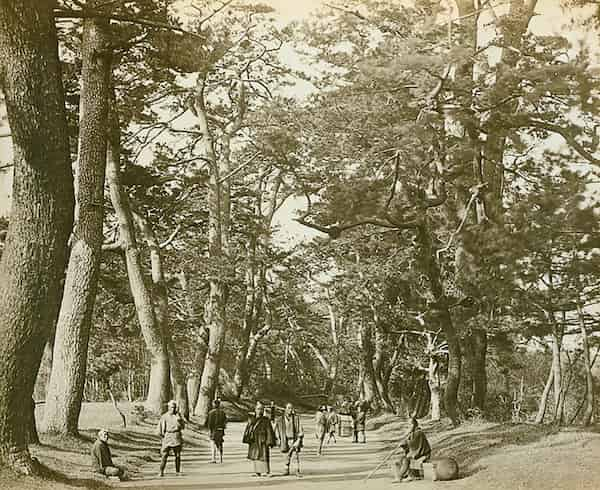

Photo of the Tōkaidō road (東海道, eastern sea route) by Felice Beato in 1865.

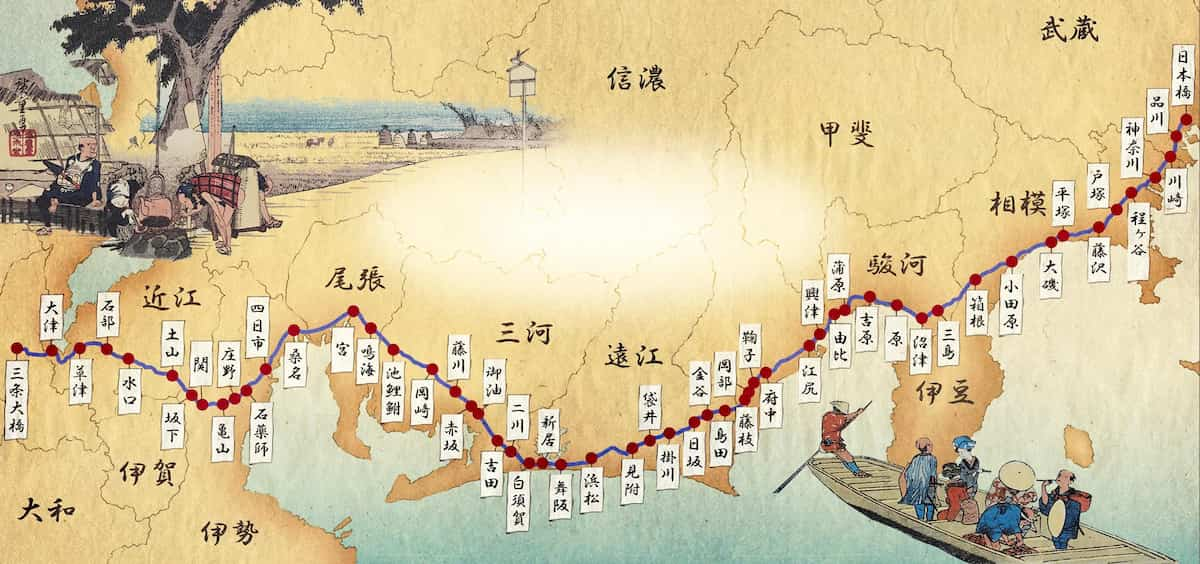

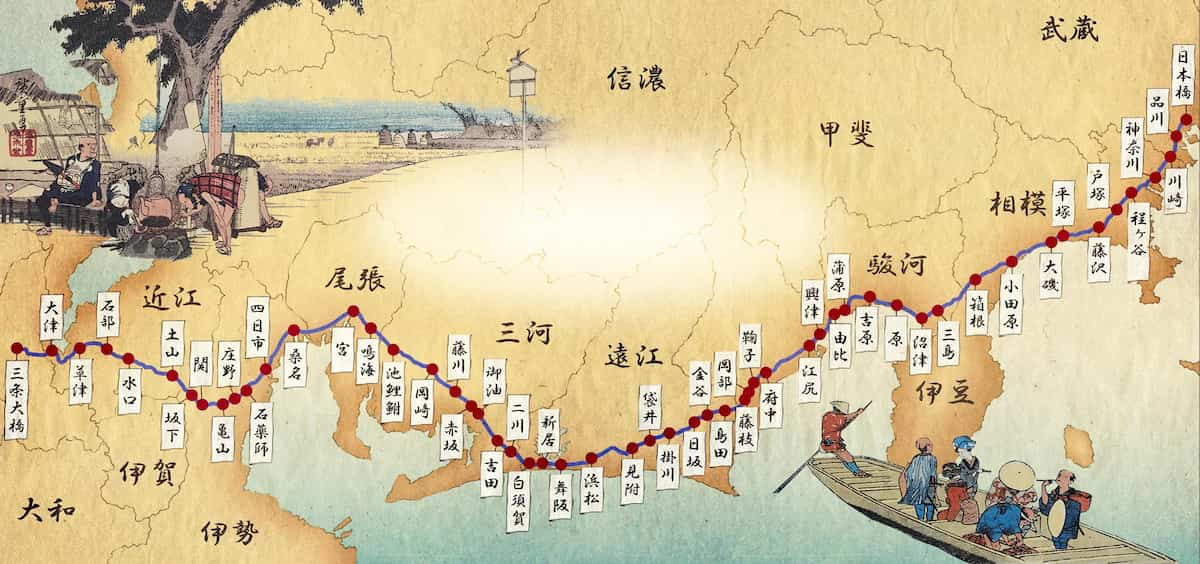

Map of the 53 Stations of the Tokaido

The Tōkaidō

The Tōkaidō was one of the Five Routes constructed under Tokugawa Ieyasu, a series of roads linking the historical capital of Edo with the rest of Japan. The Tōkaidō connected Edo with the then-capital of Kyoto. The most important and well-traveled of these, the Tōkaidō travelled along the eastern coast of Honshū, thus giving rise to the name Tōkaidō ("Eastern Sea Road"). Along this road, there were 53 different post stations, which provided stables, food, and lodging for travelers.

Marker in Nihonbashi from which distances are measured in Japan.

Memorial Portrait of Utagawa Hiroshige

Hiroshige and the Tōkaidō

In 1832, Hiroshige traveled the length of the Tōkaidō from Edo to Kyoto, as part of an official delegation transporting horses that were to be presented to the imperial court. The horses were a symbolic gift from the shōgun, presented annually in recognition of the emperor's divine status. The landscapes of the journey made a profound impression on the artist, and he created numerous sketches during the course of the trip, as well as his return to Edo via the same route. After his arrival at home, he immediately began work on the first prints from The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. Eventually, he would produce 55 prints in the whole series: one for each station, plus one apiece for the starting and ending points. But whether he actually visited all the stations and depicted them from his view is subject to academic debate, as some elements in his woodblock prints have been found to actually borrow directly from other works such as the Tōkaidō meisho zue (東海道名所図会) from 1797. An example is the view of the station Ishibe „Megawa Village“ which is almost identical to the view in the Tōkaidō meisho zue. The first of the prints in the series was published jointly by the publishing houses of Hōeidō and Senkakudō, with the former handling all subsequent releases on its own. Woodcuts of this style commonly sold as new for between 12 and 16 copper coins apiece, approximately the same price as a pair of straw sandals or a bowl of soup. The runaway success of The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō established Hiroshige as the most prominent and successful printmaker of the Tokugawa era. Hiroshige followed up on this series with The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō in cooperation with Keisai Eisen, documenting each of the post stations of the Nakasendō (which was alternatively referred to as the Kiso Kaidō).

The 53 Stations of The Tokaido - Full List

The Hōeidō edition is properly titled Tōkaidō Gojūsan-tsugi no uchi (東海道五十三次之内). Besides the fifty-three stations themselves, the series includes one print for the departure, Nihonbashi (the bridge of Japan), and a final one, the 55th print, Keishi, Kyoto, the imperial capital.

The departure - Leaving Edo : Nihonbashi, (The bridge of Japan) 日本橋

The Nihonbashi district was a major mercantile center during the Edo period: its early development is largely credited to the Mitsui family, who based their wholesaling business in Nihonbashi and developed Japan's first department store, Mitsukoshi, there. The Edo-era fish market formerly in Nihonbashi was the predecessor of the Tsukiji and Toyosu Markets. Yamamotoyama began as a tea house here in 1690. In later years, Nihonbashi emerged as Tokyo's (and Japan's) predominant financial district. The Nihonbashi bridge first became famous during the 17th century, when it was the eastern terminus of the Nakasendō and the Tōkaidō, roads which ran between Edo and Kyoto. During this time, it was known as Edobashi, or "Edo Bridge." In the Meiji era, the wooden bridge was replaced by a larger stone bridge, which still stands today (a replica of the old bridge has been exhibited at the Edo-Tokyo Museum). It is the point from which all distances are measured to the capital; highway signs indicating the distance to Tokyo actually state the number of kilometres to Nihonbashi.

1st station : Shinagawa 品川

Shinagawa-shuku (品川宿, Shinagawa-shuku) was the one of the fifty-three stations of the Tōkaidō. It is located in Shinagawa, Tokyo, Japan. Along with Itabashi-shuku (Nakasendō), Naitō Shinjuku (Kōshū Kaidō) and Senju-shuku (Nikkō Kaidō and Ōshū Kaidō), it was one of the Four Stations of Edo (江戸四宿 Edo Shishuku). It was located in the present-day Shinagawa Port area near Shinagawa Station.

2nd station : Kawasaki 品川

Shinagawa-shuku (品川宿, Shinagawa-shuku) was the one of the fifty-three stations of the Tōkaidō. It is located in Shinagawa, Tokyo, Japan. Along with Itabashi-shuku (Nakasendō), Naitō Shinjuku (Kōshū Kaidō) and Senju-shuku (Nikkō Kaidō and Ōshū Kaidō), it was one of the Four Stations of Edo (江戸四宿 Edo Shishuku). It was located in the present-day Shinagawa Port area near Shinagawa Station.

3rd station : Kanagawa 神奈川

Kanagawa-juku was established parallel to Kanagawa Port and it flourished as part of the route that goods traveled on the way to Sagami Province. Though the area had officially been designated as the place for the port to be opened, it was actually opened on the opposite shore in what is now Naka-ku, Yokohama. After the country was opened to international trade, the center of commerce was moved to the opposite shore as well. In 1889, the town of Kanagawa was established, and it eventually merged into Yokohama in 1901.

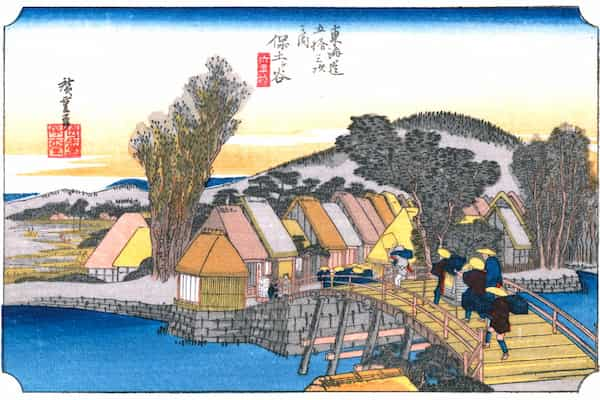

4th station : Hodogaya 程ヶ谷, 保土ヶ谷

Hodogaya-juku was established in 1601, and it was the westernmost post station in Musashi Province during the Edo period. The honjin still belongs to the same family today as the one that owned it when it was first opened. Additionally, there is a stone Buddha statue that travelers often prayed to for safety while traveling along the Tōkaidō. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831 to 1834 depicts a bridge over a stream, with two porters carrying a closed kago towards a village on the other side. By the bridge is a soba restaurant with waitresses standing in front beckoning travellers to enter.

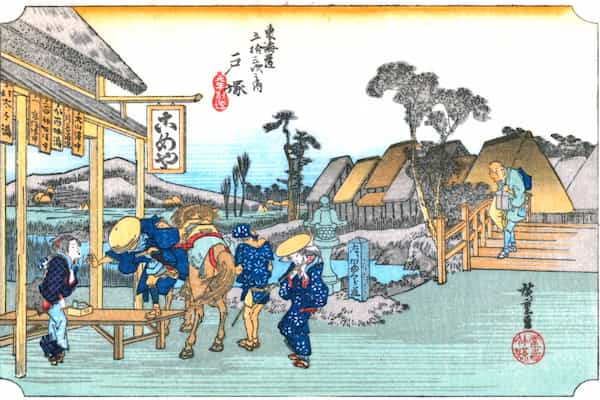

5th station : Totsuka 戸塚

Because Totsuka-juku was approximately one day's journey from Nihonbashi, it was a very common resting place for travelers at the start of the journey and the largest post station after Odawara-juku. Because of its size, there were two honjin in the post station as well, one belonging to the Sawabe family (澤辺) and the other belonging to the Uchida family (内田). Another reason for Totsuka-juku being so large was that it was also the intersection of Kamakura Kaidō and the Atsugi Kaidō. A distance marker can now be found in both Shinano-chō and Totsuka-chō. During the Bakumatsu period, when Commodore Matthew C. Perry arrived in Uraga Harbor with his Black Ships, many frightened citizens fled to Totsuka-juku. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts a traveler (one dismounting from a horse), entering into a tea-house. In the background, a wooden bridge leads across a stream to what appears to be a sizeable settlement.

6th station : Fujisawa 藤沢

Fujisawa-shuku was established as a post station on the Tōkaidō in 1601, but did not become the sixth post station until Totsuka-juku was later established. Before the establishment of the Tōkaidō, Fujisawa flourished as a “temple town” (門前町, monzen-machi) for Shōjōkō-ji, also known as "Yugyō-ji" (Japanese: 遊行寺), the head temple of the Ji-sect of Japanese Buddhism. It was also located on a fork along the Odawara Kaidō, which connected Odawara Castle and its two supporting castles, Edo Castle and Hachiōji Castle during the period of the Late Hōjō clan. The gate of post station (見附, mitsuke) toward Edo was to the east of Yugyō-ji, and the gate towards Kyoto was on the western side of the modern Odakyū Enoshima Line; these boundaries mark the general limits of Fujisawa-juku.

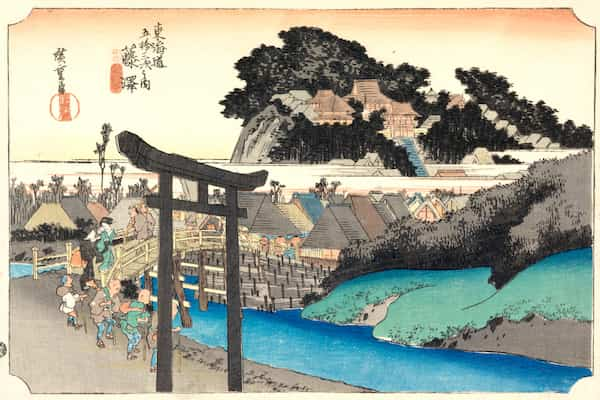

The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts a village with a bridge. In the background is the temple of Yugyō-ji on a hill, and in the foreground is a torii with a path leading to Enoshima. The bridge is crowded with pilgrims, and four blind men, apparently on their way to the Enoshima Benten Shrine are following each other alongside a stream.

7th station : Hiratsuka 平塚

Hiratsuka-juku was first established in 1601, at the orders of Tokugawa Ieyasu. In 1651, though, it merged with part of the nearby village of Yawata. In 1655, it was renamed "Shinhiratsuka-juku." During a census in 1843, the post station was found to have a population of 2,114 people and 443 houses, which included one honjin, 1 sub-honjin and 54 hatago. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 does not depict the post station at all, but instead shows a zig-zag road above marshy fields, with Mount Fuji appearing behind Shonan Daira in the background. One of the travelers is a professional courier running as part of the mail service offered along the Tōkaidō. Relays of runners could convey a message from Edo to Kyoto in 90 hours.

8th station : Oiso (Rain on a town by the coast) 大磯

Ōiso-juku was established in 1601, along with the other original post stations along the Tōkaidō, by Tokugawa Ieyasu. In 1604, Ieyasu planted a 3.9 km (2.4 mi) colonnade of pine and hackberry trees, to provide shade for the travelers. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts travelers in straw raincoats entering a village by the ocean during pouring rain. One is mounted, and the other is on foot. The road is lined with pine trees. By contrast, the Kyōka edition of the late 1830s depicts a prosperous village overlooking a wide expanse of Sagami Bay with the mountains of the Izu Peninsula on the far shore.

9th station : Odawara (Crossing the Sakawa river at a ford) 小田原

Odawara-juku (小田原宿, Odawara-juku) was the ninth of the fifty-three stations of the Tōkaidō. It is located in the present-day city of Odawara, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. It was the first post station in a castle town that travelers came to when they exited Edo (modern-day Tokyo) in Edo period Japan.

Odawara-juku was established between the mountains of Hakone and Sagami Bay, near Odawara Castle. Located near the banks of the Sakawa River, Odawara-juku was a famous post station. It is said to hold the remains of Lady Kasuga.

10th station : Hakone (High rocks by a lake) 箱根

Hakone-juku (箱根宿, Hakone-juku) was the tenth of the fifty-three stations of the Tōkaidō. It is located in the present-day town of Hakone in Ashigarashimo District, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. At an elevation of 725m, it is the highest post station on the entire Tōkaidō and was even difficult for the bakufu to maintain.

Hakone-juku was established in 1618, in a small area between Hakone Pass (on Mount Hakone) and the Hakone Checkpoint. The original Hakone-juku was on the Edo (modern-day Tokyo) side of the Hakone Checkpoint; however, the people living there at the time refused to build a honjin to create a new post station. As a result, the post town was developed on the side of the checkpoint heading towards Kyoto. The first settlers in the new post town originally lived in either Odawara-juku or Mishima-shuku, the neighboring post stations, but were forced to Hakone-juku.

11th station : Mishima (Travellers passing a shrine in the mist) 三島

In Mishima-juku, there were two honjin and 74 other minor inns for travelers. Mishima was the only post station located within Izu Province. Mishima was the traditional provincial capital of Izu from the Nara period and the location of a major Shinto shrine. Until 1759, Mishima was the location of the daikanshō, the seat of government for the hatamoto-class retainer appointed by the Tokugawa shogunate to rule over Izu Province. Additionally, because water flows from Mount Fuji to the town, it was referred to as the "Capital of Water." The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts travelers setting out in the early morning mists. One is mounted, and the other is traveling by kago. The torii of Mishima Taisha shrine is in the background. By contrast, the Kyōka edition of the late 1830s depicts a snow-covered village, with Mount Fuji in the background.

12th station : Numazu 沼津

Numazu was the easternmost post station within Suruga Province, and was the castle town of the daimyō of Numazu Domain. During its peak in the Edo period, Numazu-juku had over 1,200 buildings, including three honjin, one sub-honjin, and 55 hatago. Modern Numazu city has a local history museum displaying the history of the area. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeido edition) from 1831 to 1834 depicts travelers walking along a tree-lined river bank, towards Numazu-shuku, under a huge full moon in a deep blue sky. One of the travelers is wearing the white robes of a pilgrim, and is carrying a huge Tengu mask on his back, indicating that his destination is the famed Shinto shrine of Konpira on Shikoku.

13th station : Hara (Travellers passing Mount Fuji) 原

Hara-juku was a smaller post town on the coast of Suruga Bay between Numazu-juku and Yoshiwara-juku in Suruga Province. It is the site of many paintings because of Mount Fuji in the background. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831 to 1834 depicts two women travelers walking past a huge snowy Mount Fuji. The women are accompanied by a manservant who is carrying their luggage. By contrast, the Kyōka edition of the late 1830s depicts three small teahouses, dwarfed by a huge, red Mount Fuji which protrudes out of the picture into the top margin.

14th station : Yoshiwara 吉原

The Yoshiwara-juku was originally located near the present-day Yoshiwara Station, on the modern Tōkaidō Main Line railway, but after a very destructive tsunami in 1639, was rebuilt further inland, on what is now the Yodahara section of present-day Fuji. In 1680, the area was again devastated by a large tsunami, and the post town was again relocated and moved to its current place. Although most of the route of the Tōkaidō in Sagami and Suruga Provinces was along the seashore as the name "East Sea Route" implied, at Hara-juku travelers walked away from the sea. Also, up until this point on the journey, Mount Fuji could always be seen to the right of the travelers coming from Edo. However, as they traveled inland, they could see Mount Fuji to their left, and the view came to be called "Fuji to the Left" (左富士, Hidari Fuji). During the Edo period, there was a long colonnade of pine trees lining the route along this point. This is depicted in the classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 which shows a groom leading a horse with women travelers down a narrow path lined with pine trees with Mount Fuji to the left.

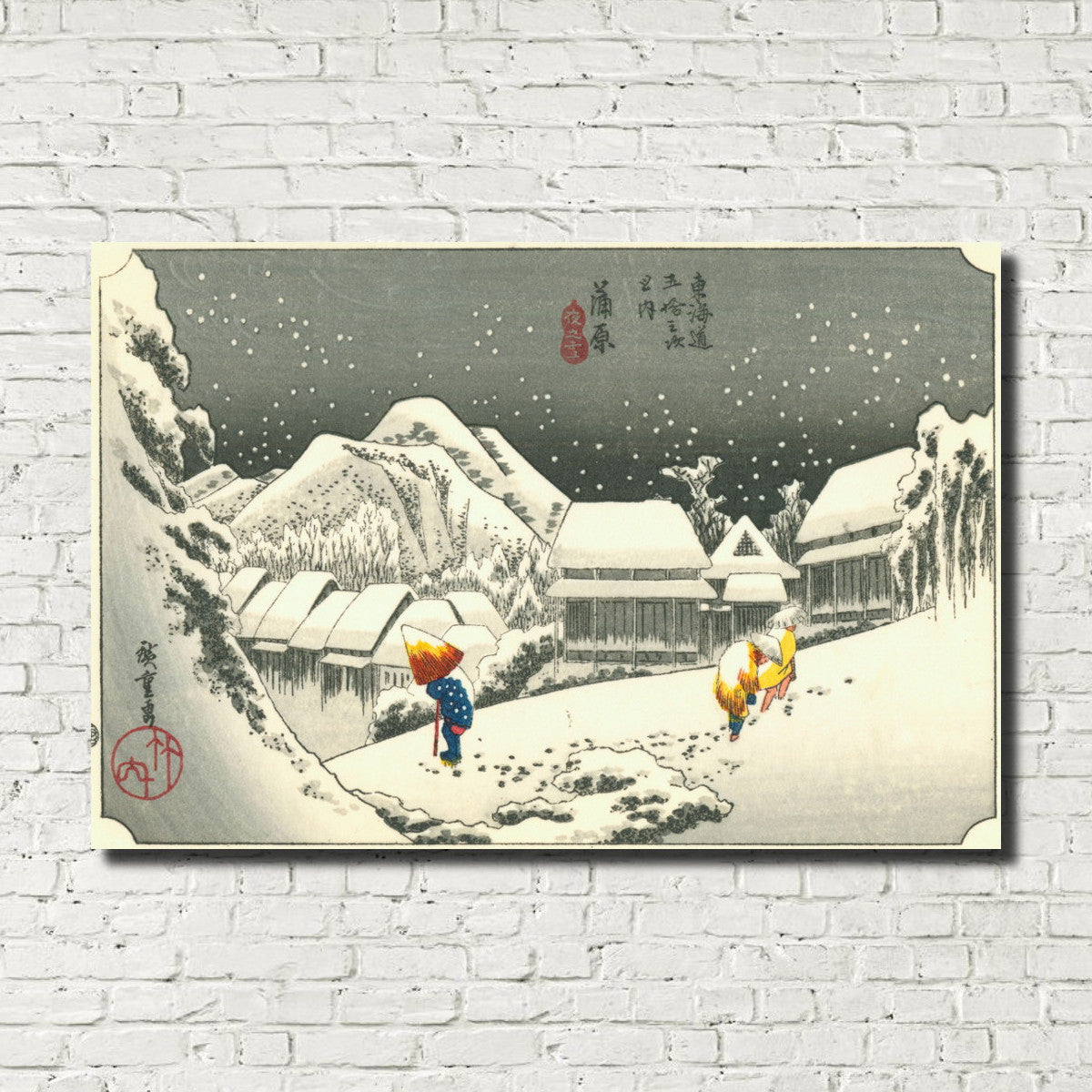

15th station : Kanbara (A village in the snow) 蒲原

The original Kanbara-juku was decimated by a flood in the early part of the Edo period, but was rebuilt shortly thereafter. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834, depicts a mountain village at nightfall, through which three people are struggling under deep snow. It is a rather strange composition, as Kanbara is located in a very temperate area warmed by the Kuroshio current offshore, and even a light snowfall is extremely rare. In Japan (as everywhere), many villages in different parts of the country have the same name. Hiroshige intended his print to represent the Kanbara which was the 15th post station on the Tokaido Road, which ran from Edo and Kyoto. But in creating his portfolio The 53 stations of the Tokaido Road, apparently he often relied on existing prints and guidebooks. It seems likely that he mistakenly used an image of a very different Kanbara: the one depicted here is probably a village in the very mountainous Gunma prefecture near the resort town of Karuizawa. It is famous as the village buried during the August 1783 eruption of Mt. Asama, which killed 466 people.

16th station : Yui (Travellers on a high cliff by the sea) 由井, 由比

At the Tōkaidō Yui-shuku Omoshiro Shukubakan, visitors can experience various aspects of life in the Edo period shukuba, ranging from schooling and lodging, to working and socializing. The area is known for its sakura ebi, a type of small shrimp. In the classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834, Hiroshige chose not to depict the post station at all, but instead shows travelers climbing a very steep mountain pass.

17th station : Okitsu 興津

Okitsu-juku was established in 1601, just before the beginning of the Edo period. At its peak, there were approximately 316 buildings and 1,668 people. Among the buildings were two honjin, two sub-honjin and 34 hatago. It was a little over 11 kilometers from the preceding post station, Yui-shuku. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts two sumo wrestlers being carried across the Okitsu River, one on a packhorse and the other in a kago.

18th station : Ejiri 江尻

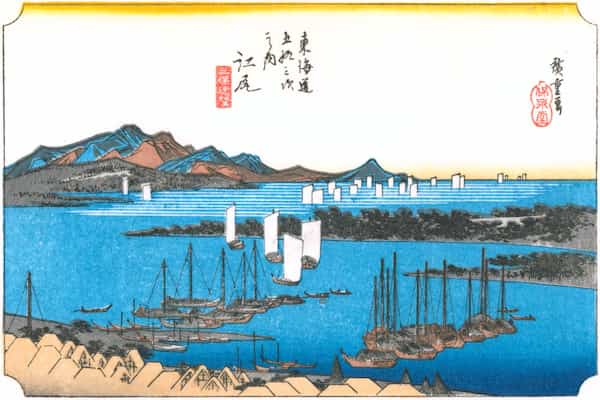

Ejiri-juku was Ejiri Castle's castle town. The castle was built in 1570, but Ejiri-juku was not officially designated a post station until the early 17th century. At its peak, it had two honjin, three sub-honjin and 50 hatago, among the 1,340 total buildings. Its population was around 6,500. Ejiri-juku gave its name to the area's railway station, until it was renamed Shimizu Station in 1934. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts a view over the Miho no Matsubara with boats anchored in the foreground in front of a fishing village, with others sailing in Suruga Bay.

19th station : Fuchū 府中, 駿府

Fuchū-shuku (府中宿, Fuchū-shuku) was the nineteenth of the fifty-three stations of the Tōkaidō. It is located in what is now part of the Aoi-ku area of Shizuoka, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan.

The post station of Fuchū-shuku was also a castle town for Sunpu Castle in the former Suruga Province. Sunpu Castle The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831 to 1834 depicts travellers crossing the Abe River to the west of the post station. A woman is being carried in a kago, while other people are fording the stream on foot.

20th station : Mariko (A roadside restaurant) 鞠子, 丸子

Mariko-juku was one of the smallest post stations on the Tōkaidō. Old row-houses from the Edo period can be found between Mariko-juku and Okabe-juku, its neighboring post station, in Utsuinotani. This post town also had strong ties to the Minamoto, Imagawa and Tokugawa clans. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts two travellers at a wayside restaurant which name is Chouji-ya(丁子屋), it is noted for Tororo-Jiru (grated japanese yam soup) and founded in 1596, from which another traveller has just departed.

21st station : Okabe 岡部

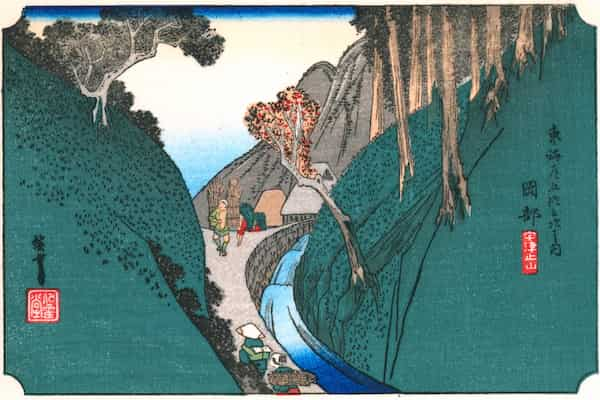

Though most post stations along the Tōkaidō were built the first year the route was established; however, Okabe-juku was built one year later in 1602. It only had a population of 16 when it was first established and even by 1638], there were only 100 people in the town, making it a rather small post town; however, it was still able to flourish. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts a mountain stream between steep green banks, with the roadway a narrow path walled in on one side by a stone wall. Okabe-juku's hatago, Kashiba-ya, prospered during the Edo period; however, it was destroyed by fire in 1834. After it was rebuilt in 1836, it was eventually named nationally designated Important Cultural Property. In 2000, it was reopened as an archives museum.

22nd station : Fujieda 藤枝

Fujieda-juku was a castle town of the Tanaka Domain. Additionally, it was a post station along the Unuma Kaidō, which ran to the salt-producing area of Sagara. It flourished as a commercial town and, at its prime, hosted 37 hatago. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts the actual business of the shukuba as a relay station to change horses and coolies to permit the rapid transmission of high priority messages and goods between Edo and Kyoto. At the beginning of the Meiji period, when the Tōkaidō Main Line railway was being built, residents were worried about the smoke and ash from the newly developed steam locomotives would ruin their green tea crop, and decided to block construction of the line. As a result, Fujieda Station (now part of Central Japan Railway Company) was built approximately three kilometers from the town, which led to a decline in prosperity for the old town. However, after Fujieda became a city, its area expanded greatly and has become an industrial community. Additionally, it serves as a bedroom community to Shizuoka. Neighboring post towns

23rd station : Shimada 島田

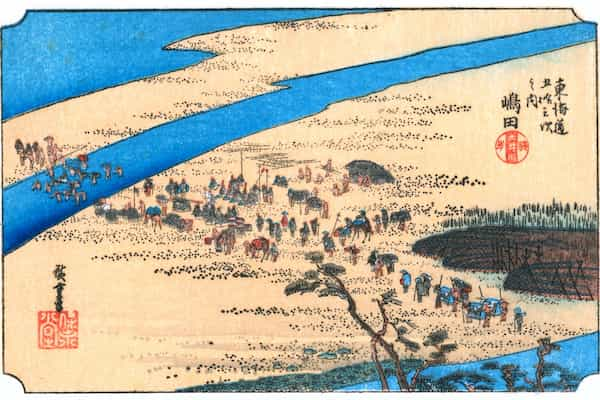

Shimada-juku was located on the left bank (Edo side) of the Ōi River, just across from its neighboring post town, Kanaya-juku. As part of the outer defenses of the capital of Edo, the Tokugawa shogunate expressly forbid the construction of any bridge or ferry service over the Ōi River, forcing travelers to wade across its shallows. However, whenever the river flooded due to strong or long rains, crossing the river became nearly impossible. During periods of long rains, visitors were sometimes forced to stay at Shimada-juku for several days, increasing the amount of money they spent. A common saying about Shimada-juku was "You can travel the 8 ri to Hakone, but to cross it, you must cross the uncrossable Ōi River" (箱根八里は馬でも越すが 越すに越されぬ大井川, Hakone hachiri wa uma demo kosu ga / kosu ni kosarenu Ōigawa). The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831 to 1834 depicts travelers crossing the shallows and sand banks of the Ōi River. Some are on foot, some are carried by porters and others are riding in kago.

24th station : Kanaya (Crossing a wide river) 金屋, 金谷

Kanaya-juku was built up on the right bank of the Ōi River across from Shimada-juku. There were over 1,000 buildings in the post town, including three honjin, one sub-honjin and 51 hatago. Travelers had an easy travel to Nissaka-shuku, which was about 6.5 km (4.0 mi) away. However, whenever the river's banks overflowed, travelers were not able to pass through Kanaya and on to Shimada-juku, as the Tokugawa shogunate had expressly forbidden the construction of any bridge on the Ōi River. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeido edition) from 1831–1834 depicts a daimyō procession on sankin-kōtai crossing the river. The daimyō is riding in a kago, held above the water by a makeshift platform carried by numerous porters. His retainers are attempting to wade across the river. In the background, a small village is shown in the foothills.

25th station : Nissaka 日坂

Nissaka-shuku was located at the western entrance to Sayo no Nakayama (小夜の中山), regarded as one of the three difficult mountain passes along the Tōkaidō. At the western entrance of Nissaka-shuku is Kotonomama Hachimangū Shrine (事任八幡宮, Kotonomama Hachimangū). Originally, various characters were used for Nissaka, including 入坂, 西坂 and 新坂, as it had been nothing more than a small town located between Kanaya-juku on the banks of the Ōi River and Kakegawa-juku, a castle town that was an intersection along an old salt trading route. When Nissaka-shuku was established as part of the Tōkaidō at the start of the Edo period, the characters for its name officially became 日坂. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts travellers on a steep road in forbidding dark mountains contemplating a large boulder in the road. The stone was a noted landmark on Tōkaidō called the "Night weeping stone". According to legend, the bandits attacked and murdered a pregnant woman on this spot. After she died, a passing priest heard the stone call out for him to rescue the surviving infant. The Tōkaidō Main Line railroad, established during the Meiji period, was built to avoid the difficult pass and, as a result, the fortunes of Nissaka-shuku began to fall. It began to prosper again when Route 1 was rebuilt after World War II, with the new route running through Nissaka. In 1955, the village of Nissaka in Ogasa District merged with the neighboring city of Kakegawa.

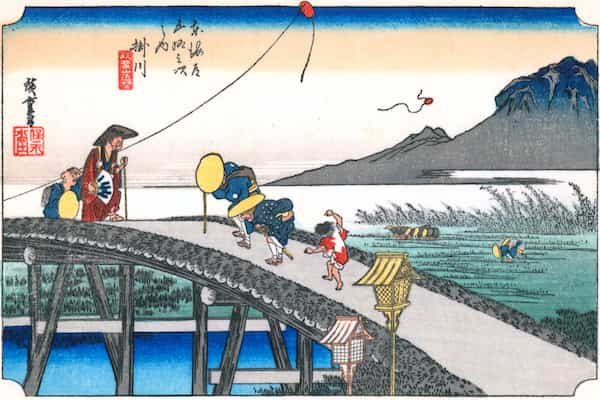

26th station : Kakegawa 掛川

Kakegawa-juku was originally the castle town of Kakegawa Castle. It was famous because Yamauchi Kazutoyo rebuilt the area and lived there himself. It also served as a post station along a salt road that ran through Shinano Province between the modern-day cities of Makinohara and Hamamatsu. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts travelers crossing a trestle-bridge. An old couple is struggling against a strong wind, followed by a boy making a mocking gesture; another boy is watching a kite up in the air. In the background, peasants are planting rice and in the distance, Mount Akiba is shown in the mists.

27th station : Fukuroi 袋井

Fukuroi-juku was developed later than most of the other post stations, as it was not established until 1616. It is 9.7 km from Kakegawa-juku, the preceding post town. At its peak, Fukuroi-juku was home to 195 buildings, including three honjin and 50 hatago. Its total population was approximately 843 people. Because it was in the vicinity of the former Tōtōmi Province's three major temples, it also flourished as the gateway to the three temples. The three temples were: Hattasan Sonei-ji (法多山尊永寺), Kasuisai (可睡斎) and Yusan-ji (油山寺). The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts a couple of travelers sheltering at a wayside lean-to, in front of which a woman stirs a large kettle hung from the branch of a large tree. The surrounding area appears to be featureless rice fields, with little indication of a post town.

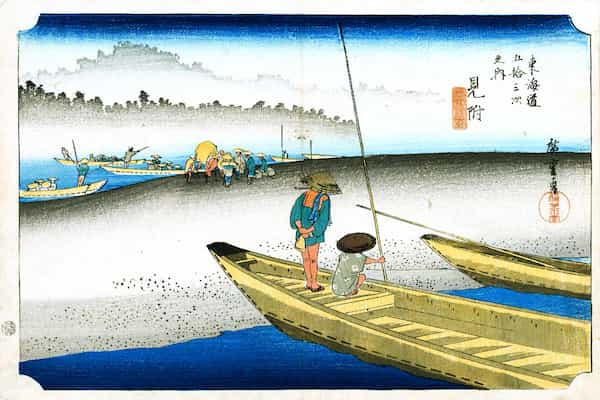

28th station : Mitsuke 見附

Mitsuke-juku is located on the left bank of the Tenryū River, but boats generally used the nearby Ōi River, as it had a deeper channel and fewer difficult places to navigate. However, much like Shimada-juku, whenever the Ōi River overflowed, travel through the town became impossible. In addition to being a post station, Mitsuke-juku also flourished as the entry to Tōtōmi Province's Mitsuke Tenjin Shrine (見附天神, Mitsuke Tenjin) and as the point at which the Tōkaidō separated with a hime kaidō. When the Tōkaidō Main Line railway was established, the train station was built to the south of Mitsuke in the village of Nakaizumi. In 1940, Mitsuke and Nakaizumi merged, forming the town of Iwata, which became a city in 1948. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts travelers changing boats on a sandbank while crossing the Tenryū River by ferry.

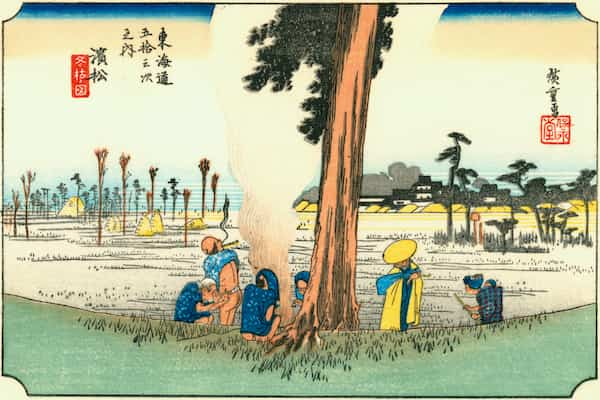

29th station : Hamamatsu 浜松

During the Tenpō era (1830–1844), Hamamatsu-juku was located in Hamamatsu Castle's castle town. At the time, there were six honjin and 94 hatago for travelers to use, making it the largest post station in Tōtōmi and Suruga provinces. At the time, it was located on the right bank of the Tenryū River, but, over time, the river's course changed, so the post station is now approximately six kilometers from the river's edge. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts a rural scene with Hamamatsu Castle and the town in the far distance. A group of peasants are warming themselves by a bonfire, with a traveler looking on.

30th station : Maisaka 舞阪

Maisaka-juku was located on the eastern shores of Lake Hamana (浜名湖, Hamana-ko). Travelers crossed the lake to reach Arai-juku, the next post station on the Tōkaidō. A pine colonnade from the Edo period remains today and stretches from Maisaka Station to the entrance for the post station. Many visitors still come to the area, which is popular with fishermen and clam-diggers. However, none of the old streetscape remains today; only part of one old sub-honjin remains. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831 to 1834 depicts a small port, with Mount Fuji having become a very small landmark in the distance.

31st station : Arai 荒井, 新居

Arai-juku was located on the western shores of Lake Hamana (浜名湖, Hamana-ko). Travelers crossed the lake to reach Maisaka-juku, the previous post station on the Tōkaidō. Though there were many checkpoints along the Tōkaidō, the Arai Checkpoint is the only one that existed both on land and on the water. Both the checkpoint and post station were often damaged from earthquakes and tsunami, which led to them both being moved to different locations. The current location was established after the earthquake of 1707. The existing checkpoint building was used as a school after the checkpoint was abolished at the start of the Meiji period. It is now preserved as a museum dedicated to the history and culture of the post stations. The Kii-no-kuni-ya (紀伊の国屋), a preserved hatago (旅籠) still remaining today, served as a rest spot for official travelers coming from Kii Province further south. It is now a local history museum. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hoeido edition) from 1831–1834 depicts a daimyō procession on sankin-kōtai crossing between Maisaka-juku and Arai-juku by boat. The daimyō is in a large vessel with his family crest, while his retainers follow in a smaller boat with the baggage.

32nd station : Shirasuka 白須賀

Originally, Shirasuka-juku was located very close to the shore of the ocean. However, in the earthquake of 1707, the earthquake and its tsunami devastated the region. After that, the post station was moved to its present location on a plateau. Before the 1707 earthquake, it was recorded to have 27 inns for travelers, making it a middle-sized post station. When the post station was decommissioned in 1889, it was replaced with the new town of Shirasuka, which later merged with the city of Kosai in 1955. During the Meiji period, the Tōkaidō Main Line was established. However, the train line did not come through Kosai and major developments in the area were kept to a minimum. As a result, there are still a few areas with buildings from the Edo period in existence today. There is also a historical archives museum that was established to mark the 400th anniversary of the founding of the post station, with the purpose of expanding knowledge of the culture and history of the post station. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeido edition) from 1831–1834 depicts a daimyō procession on sankin-kōtai, heading towards Edo from one of the domains in eastern Japan.

33rd station : Futagawa 二川

Futagawa-juku was established in 1601 when two villages, Futagawa (二川村 Futagawa-mura) and Ōiwa (大岩村 Ōiwa-mura), in Mikawa Province's Atsumi District were directed with caring for travelers. However, as the towns were rather small and were separated by 1.3 km, the original setup did not last long. In 1644, the Tokugawa shogunate moved the village of Futagawa further to the west and the village of Ōiwa further to the east, before reestablishing the post station in the Futagawa's new location. An ai no shuku was built in Ōiwa. Futagawa-juku was located approximately 283 kilometres (176 mi) from Edo's Nihonbashi, the start of the Tōkaidō. Furthermore, it was 5.8 kilometres (3.6 mi) from Shirasuka-juku to the east and 6.1 kilometres (3.8 mi) from Yoshida-juku to the west. Futagawa-juku itself stretched for about 1.3 kilometres (0.81 mi) along the road and held one honjin, one waki-honjin, and about 30 hatago. The honjin was destroyed many times by fire, but was always rebuilt. The honjin that existed after the Meiji period was rebuilt in 1988 and became an archives museum. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts a rather bleak landscape, with weary travellers approaching an isolated teahouse. During the Meiji Restoration when rail lines were being laid, the tracks ran through the town, but there was no station. After realizing the value of railroad, the town petitioned for a station and Futagawa Station was eventually built between Futagawa and Ōiwa. As the station was built slightly apart from Futagawa, remnants from the Edo period post station can be found approximately two kilometers from the station.

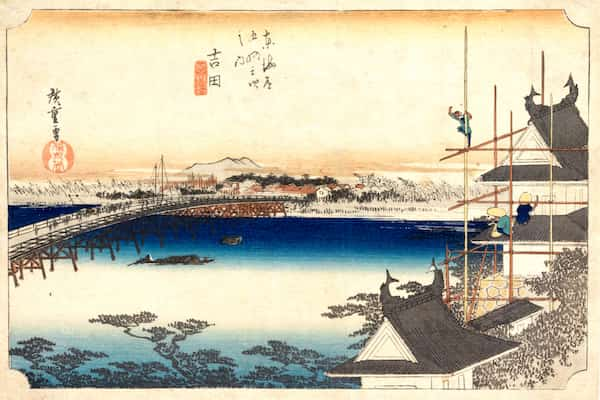

34th station : Yoshida 吉田

Yoshida-juku was established in 1601 as a post station within the castle town surrounding Yoshida Castle, an important feudal domain and port town in Mikawa Province. Yoshida had a bridge which crossed the Toyokawa River. This was one of the few bridges permitted on the Tōkaidō by the Tokugawa shogunate. One the larger post stations on the Tōkaidō, it stretched for 2.6 kilometers along the highway, and in a census taken in 1802, there were two honjin, one waki-honjin and 65 hatago to serve the travelers. The town as a whole consisted of approximately 1,000 buildings and had a population of 5,000 to 7,000 people. As with neighboring Goyu-shuku and Fukagawa-juku, it had a reputation for its meshimori onna. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts the famous bridge at Yoshida, as well as Yoshida Castle.

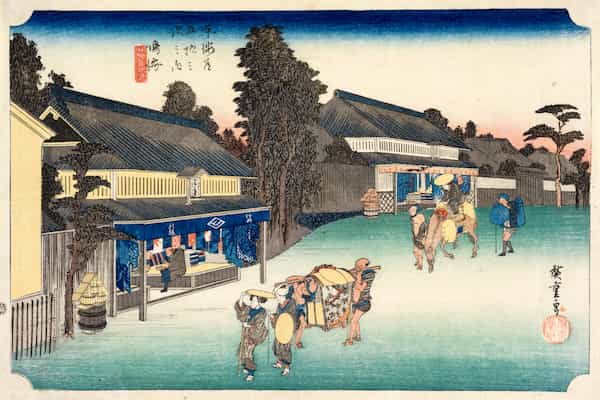

35th station : Goyu 御油

Goyu-shuku was established in 1601, at the behest of Tokugawa Ieyasu. At its most prosperous, there were four honjin in the post town, though there were never less than two at any point. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831–1834 depicts the main street of the post town at dusk, with aggressive female touts (for which the post station was infamous) attempting to drag travellers into teahouses and inns for the night. During the Meiji Restoration, the central office for the Hoi District, making it the center of the district. However, when the Tōkaidō Main Line was laid down and bypassed Goyu-shuku, it did not receive the same prosperity as Mito and Gamagōri. Later, when Nagoya Railroad laid down what was to become the Meitetsu Nagoya Main Line, a train station was opened in former Goyu-shuku. The prosperity that the town had before the Meiji Restoration, however, did not return, because express trains did not stop at the station. This eventually led to the district's offices and police stations being moved to the nearby Kō-chō area of Toyokawa. In 1959, the former town of Goyu merged with the city of Toyokawa.

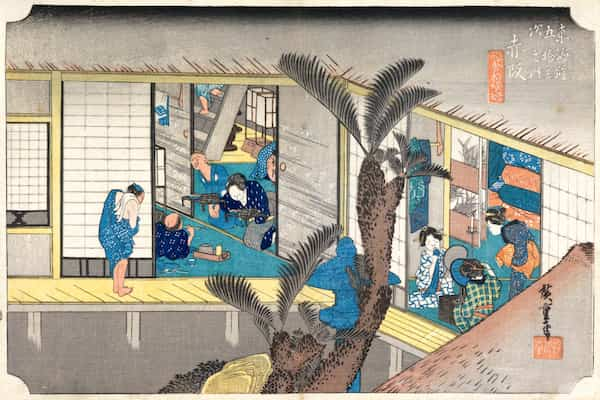

36th station : Akasaka 赤坂

Along with the preceding Yoshida-juku and Goyu-shuku, Akasaka-juku was well known for its meshimori onna. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hoeido edition) from 1831–1834 depicts a typical inn; the scene is divided in half by a sago palm in the center. To the right, travellers are taking their evening meal, and to the left, prostitutes are putting on make-up and preparing for the evening entertainment. Due to its reputation, Akasaka was a popular post station with many travellers.

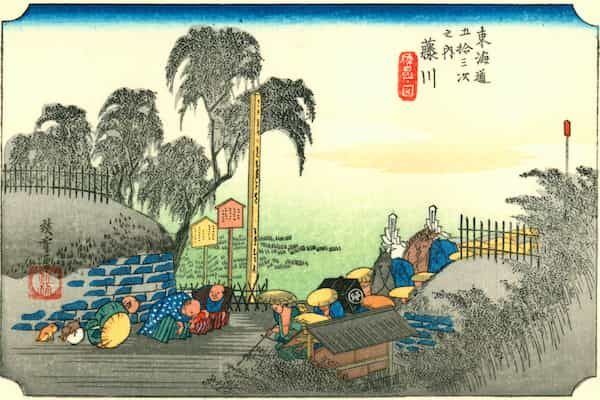

37th station : Fujikawa 藤川

Fujikawa-shuku (藤川宿, Fujikawa-shuku) was the thirty-seventh of the fifty-three stations of the Tōkaidō. It is located in the present-day city of Okazaki, in Aichi Prefecture, Japan. It was approximately 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) from Akasaka-juku, the preceding post station. Another accepted reading for this post town is "Fujikawa-juku." At its peak, Fujikawa-juku was home to 302 buildings, including one honjin, one sub-honjin and 36 hatago. Its total population was approximately 1,200 people. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831 to 1834 depicts a daimyō procession on sankin-kōtai entering the post station, which would have been a common occurrence. Three commoners are shown as kneeling as the lord's retinue passes. The Okazaki city government has been working actively on preserving this old post town as a tourist destination. In addition to creating the Fujikawa-shuku Archives Museum within the preserved waki-honjin, detailing the history of the post town, the city has preserved a number of old structures such old street lights, and traditional houses with lattice windows. A line of old pine trees extending for approximately a kilometer marks the location of the Tōkaidō road.

38th station : Okazaki 岡崎

Okazaki-shuku was a part of the flourishing castle town surrounding Okazaki Castle, the headquarters for Okazaki Domain. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831 to 1834 depicts a Yahagibashi, one of the few bridges permitted by the Tokugawa shogunate on the Tōkaidō, and one of the longest bridges built in Japan during the early Edo period. Okazaki Castle is depicted in the distance on the far shore of the river. Following the Meiji restoration, with the construction of railroads, the route of what became the Tokaido Main Line was laid down through the nearby village of Hane (羽根村 Hane-mura) to the south. Unlike Goyu-shuku and Akasaka-juku, but this did not cause a huge economic decline to Okazaki-shuku. There was a horse-drawn rail line connecting Okazaki to the train station, as well as a teachers' school, which kept the town alive. On the other hand, Okazaki was not able to compete with the growth of Toyohashi, which was located directly on the railway, and which gained city-status first. Because of fires during World War II and the subsequent rebuilding of Okazaki in the post-war years, there are few remnants of the post town remaining today.

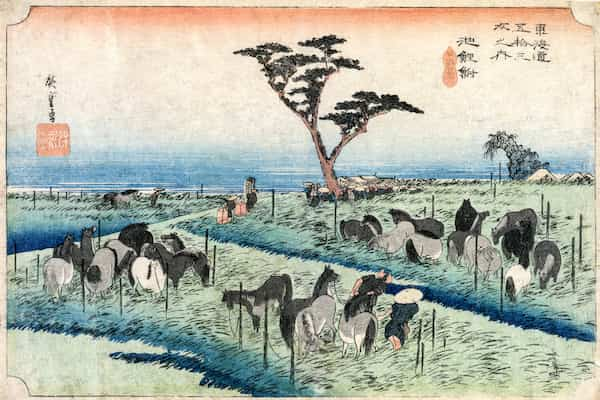

39th station : Chiryu 池鯉鮒, 知立

Chiryū-juku was noted for a famed Shinto shrine, the Chiryū Daimyōjin, and also for its flourishing horse market, held in late April to early May of each year. Tokugawa Ieyasu ordered that the post station plant pine trees along through route of the highway before and after the town. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831 to 1834 depicts horses, and also one of the pine trees. Hiroshige entitled the work Summer Horse Market (首夏馬市, Shuka Umaichi). Despite the construction of railroads following the Meiji restoration the horse market continued into the Shōwa period, and most of the pine trees survived until the 1959 Isewan Typhoon.

40th station : Narumi 鳴海

Narumi-juku had a population of 3,643 people at its peak. The post station also had 847 buildings, including one honjin, two wakihonjin and 68 hatago. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831 to 1834 depicts travellers passing by open-fronted shops selling tie-died cloth, typically used for making yukata summer kimono, which was a local speciality of the region. The railroad bypassed Narumi-juku in the Meiji period, and a portion of the old town is preserved as a tourist attraction.

41st station : Miya 宮

In addition to being a post station on the Tōkaidō, Miya-juku was also part of the Minoji (a minor route which runs to Tarui-juku on the Nakasendō) and the Saya Kaidō. As a result, it had the most hatago of any post station along the Tōkaidō, with two honjin, one wakihonjin and 248 lesser inns. The classic ukiyo-e print by Andō Hiroshige (Hōeidō edition) from 1831 to 1834 depicts two gangs of men dragging a portable shrine cart (not shown) past a huge torii gate. The torii gate is the symbol of a Shinto shrine, and the name of "Miya" also means a "Shinto shrine". The shrine in question is the famous Atsuta Shrine, one of the most famous in Japan and a popular pilgrimage destination in the Edo period. The area is now part of downtown Nagoya metropolis.

42nd station : Kuwana 桑名

Kuwana-juku was located in the castle town of Kuwana Domain, which was a major security barrier on the Tōkaidō for the Tokugawa shogunate. The post station was located on the western shores of the Ibi River. Between Kuwana and the next station to the west, Miya-juku, were the Kiso Three Rivers, which included the Nagara River and the Kiso River in addition to the Ibi River. As all three rivers were near their outlets to Ise Bay, their channels were wide, and the shogunate forbid the construction of any bridges, as this would facilitate the crossing of any army from the west across the rivers towards Edo. This posed a problem however for travelers. The preferred connection for many travelers between Kuwana-juku and Miya-juku was by the Shichiri no watashi (七里の渡し), a roughly 28-kilometer boat ride across Ise Bay. A large torii gate on the Kuwana side of the crossing indicated that this was also on the route for pilgrims to the Ise Grand Shrine. For those leery of travel on the ocean, the alternative was the Saya Kaidō (佐屋街道), which consisted of a shorter riverboat ride, the Sanri no watashi (三里の渡し) which connected Kuwana-juku with Saya-juku (佐屋宿), a post station in Owari Province, and thence overland via the Saya Kaidō highway to Miya-juku, with three intermediate post stations en route. This route was roughly eight kilometers longer than the direct sea route, and was much more expensive in terms of tolls, but was also much quicker. This route was constructed by Owari Domain for the visit of Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu to Kyoto, and was the route used two centuries later by Emperor Meiji when he first travelled from Kyoto to Tokyo.

43rd station : Yokkaichi 四日市

Utagawa Hiroshige's ukiyo-e Hōeidō edition print of Yokkaichi-juku dates from 1833 -1834. The print illustrates a windy day with a man racing after his hat, which has been blown away by the wind and another man crosses a small bridge over the Sanju River, depicted here as a small stream. The post town is depicted as a small collection of huts in the middle of a marsh, almost hidden by the reeds.

44th station : Ishiyakushi 石薬師

Utagawa Hiroshige's ukiyo-e Hōeidō edition print of Ishiyakushi-juku dates from 1833 -1834. The print does depicts the temple in a grove of trees on the left and a village on the right, with the Suzuka Mountains in the background. Bales of rice indicate that the setting is autumn, and reflect the rural character of the post town, and the closed temple gate indicate that the time is dusk.

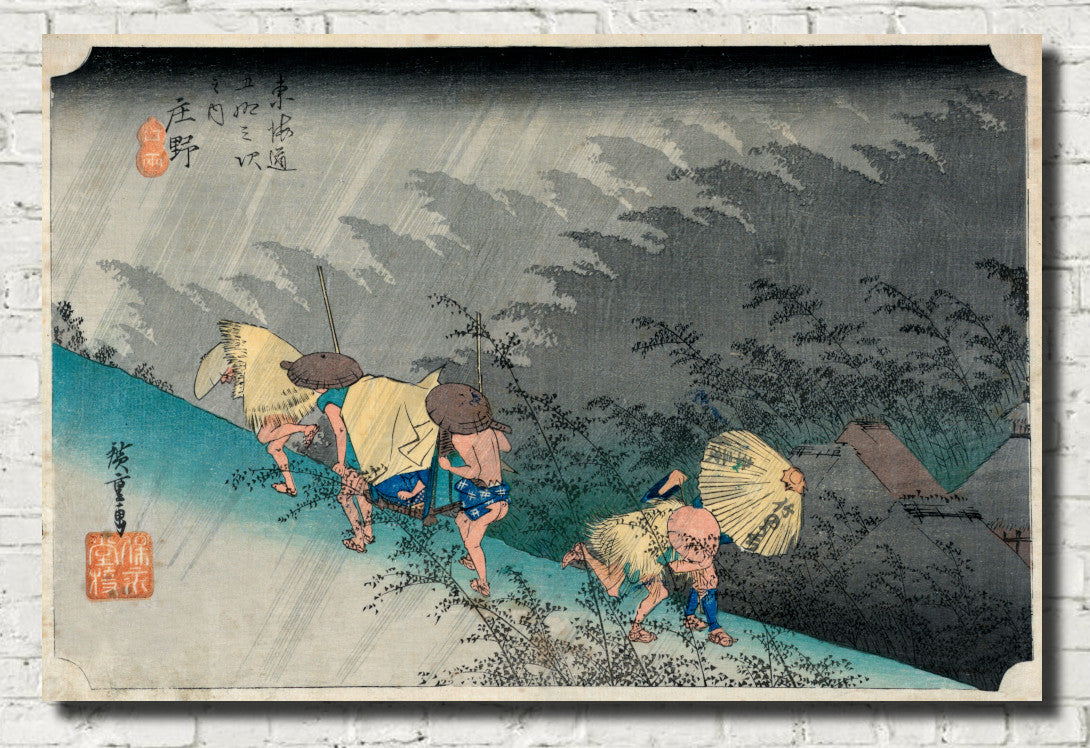

45th station : Shōno (Travellers surprised by sudden rain) 庄野

Utagawa Hiroshige's ukiyo-e Hōeidō edition print of Shōno-juku dates from 1833 -1834. It is titled Shōno's White Rain (白雨, Haku'u). and depicts a group of travelers with straw raincoats and umbrellas, caught in a sudden summer thunderstorm and hurrying towards shelter. Kago (palanquin) bearers with a seated passenger are struggling up the slope, and a farmer with a straw raincoat and a traveler with an umbrella are struggling down the slope in the opposite direction. The thatched roofs of the post station are depicted in the lower right corner of the composition.

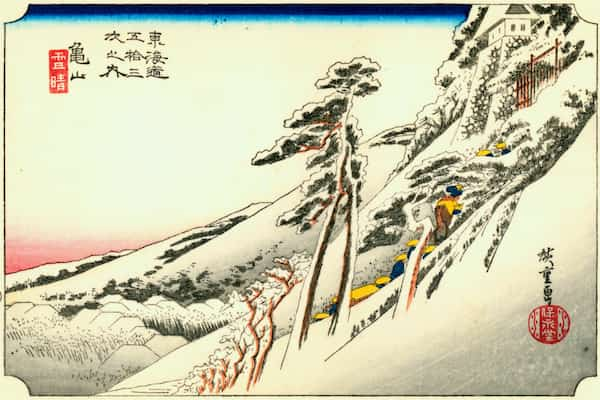

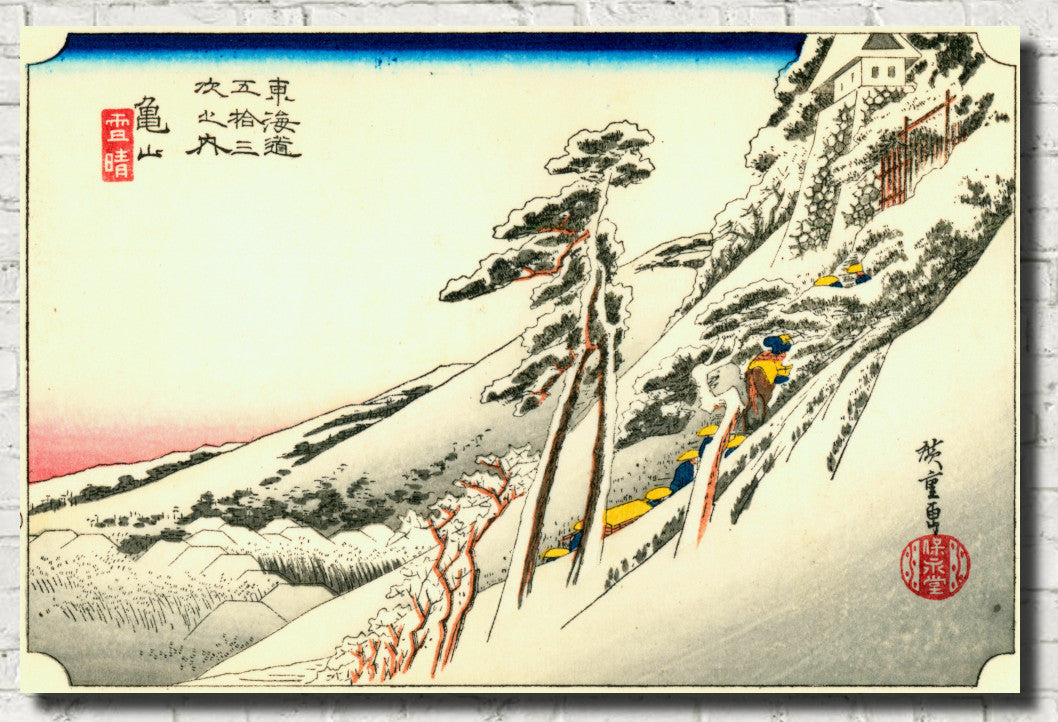

46th station : Kameyama (A castle on a snow-covered slope) 亀山

Utagawa Hiroshige's ukiyo-e Hōeidō edition print of Kameyama-juku dates from 1833 -1834. The print depicts travelers climbing a steep hillside to the Kyoguchi Gate, with the roofs of a town extending at a right angle to then left of the composition. Inexplicably, Hiroshige depicted the scene in mid-winter, with very heavy snows, although the Kameyama area is not noted for severe winters.

47th station : Seki (Departure from the inn) 関

Utagawa Hiroshige's ukiyo-e Hōeidō edition print of Seki-juku dates from 1833 -1834. The print depicts the early morning preparations for departure of a daimyō procession on sankin-kōtai from one of the honjin. A number of lower-ranking retainers with long spears are tying their travel hats and sandals, while in the background, a number of higher ranking samurai with their two swords are waiting by the entrance for other members of the party to appear. The sky is still dark, and a number of chōchin travel lanterns are in evidence.

48th station : Sakashita 坂下

Utagawa Hiroshige's ukiyo-e Hōeidō edition print of Sakashita-juku dates from 1833 -1834. The print does not depicts the post station at all, but instead shows an open teahouse, looking across a ravine to the blue heights of the Mount Fudesute in the Suzuka Mountains. According to folklore, during the Muromachi period, when the famed painter Kanō Motonobu attempted to paint this mountain with its landscape of strongly-shaped rocks and groves of maple, pine and azaleas, the shifting light caused by clouds and haze caused him to throw down his paintbrush in frustration. The view of the mountain was a famed scenic spot in Edo period guidebooks, and the tea house within Suzuka Pass with a view of the mountain was a popular resting place for travelers.

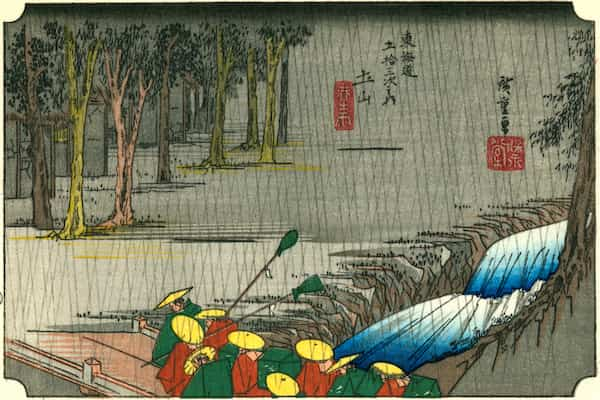

49th station : Tsuchiyama 土山

Utagawa Hiroshige's ukiyo-e Hōeidō edition print of Tsuchiyama-juku dates from 1833 -1834. The print depicts a daimyō procession crossing a raging torrent in a downpour. The men are wearing hats and raincoats, and are looking downward as they struggle across a wooden bridge. The post station is in the upper left corner: an unwelcoming row of dark buildings half hidden by a forbidding row of dark trees. This motif comes from a Edo Period min'yō folk song about the Suzuka pass which was popular with packhorse handlers: "The slopes are shining, the hills are cloudy, and the earthen mountains rain", with "earthen mountains" as the literal translation of "Tsuchiyama".

50th station : Minakuchi 水口

Utagawa Hiroshige's ukiyo-e Hōeidō edition print of Minakuchi-juku dates from 1833 -1834. The print depicts a straggling row of thatch-roofed structures. In the foreground are two women (one with a baby on her back) hanging up strips of kanpyō to dry on lines, while a third woman with a knife is peeling more from a calabash. More strips of drying kanpyō are shown on the fences of the buildings in the background. A solitary traveller is walking away from the viewer on the road.

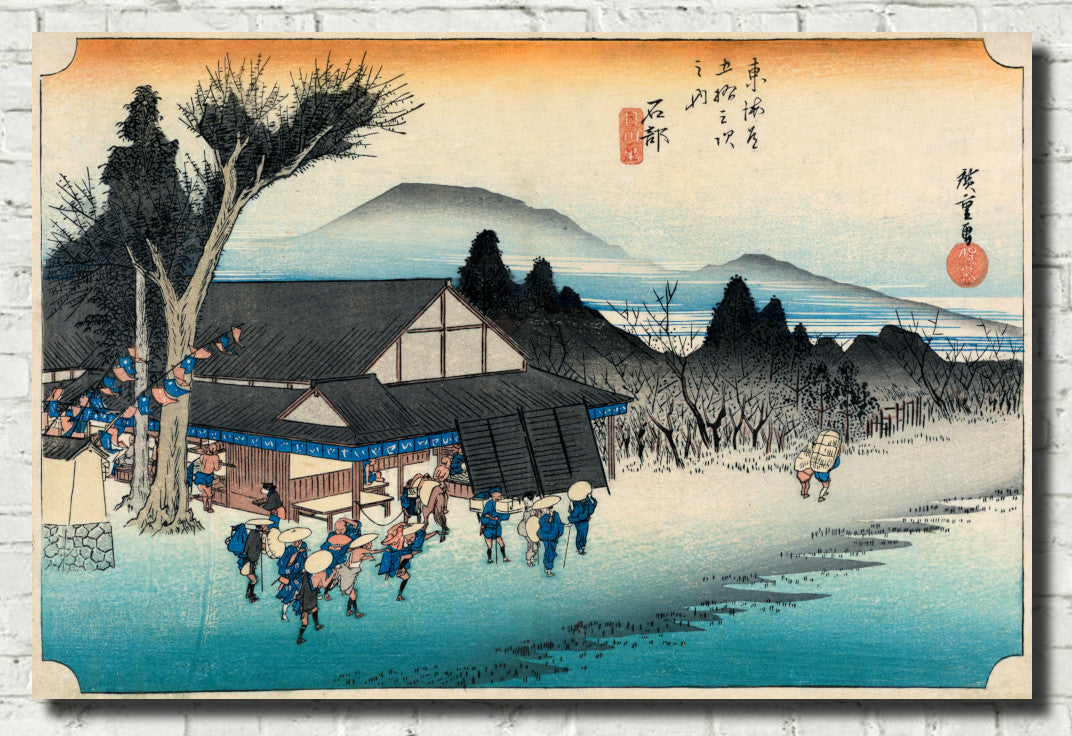

51st station : Ishibe 石部

Utagawa Hiroshige's ukiyo-e Hōeidō edition print of Ishibe-juku dates from 1833 -1834. The print does not actually show the post station at all, but instead shows a tea house called "Ise-ya", located at "Megawa no Sato", which was on the highway between Kusatsu-juku and Ishiba-juku, but actually closer to Kusatsu-juku. This shop was famous for its tokoroten, a gelatinous sweet made from agar, and kuromitsu, a black sugar syrup. A group of travelers are dancing and cavorting in front of the shop while three women with traveling hats and walking sticks look on in amusement. A couple of other travelers, heavily laden, are some distance further down the road.

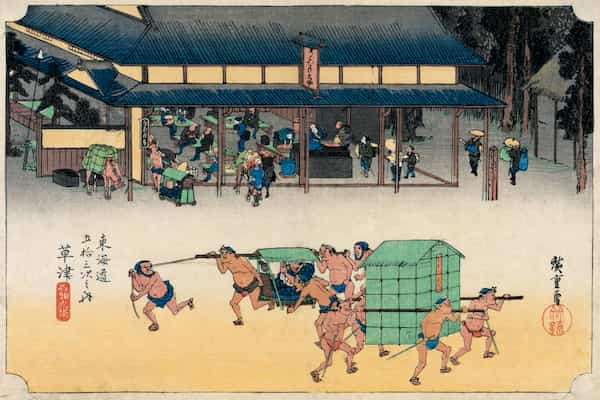

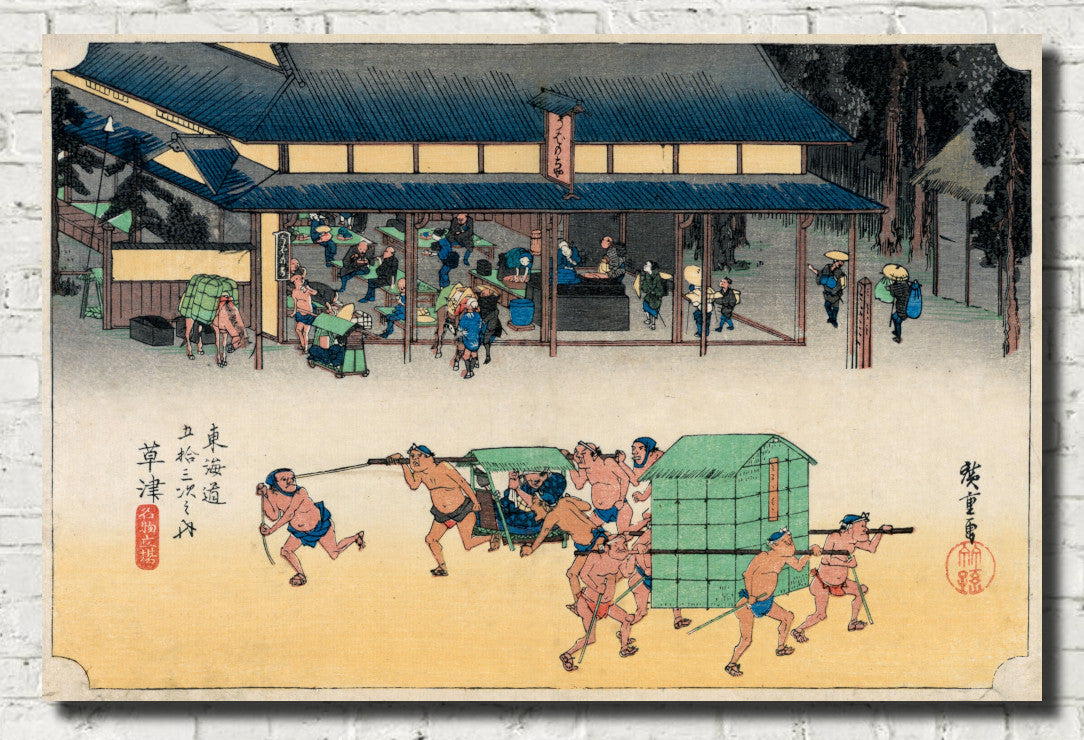

52nd station : Kusatsu 草津

Utagawa Hiroshige's ukiyo-e Hōeidō edition print of Kusatsu-juku dates from 1833 -1834. The print depicts a busy scene within the post station itself in front of the open-fronted Yōrō-tei (養老亭) tea house in which many patrons are enjoying Ubagamochi (姥が餅), a sweetened sticky rice cake which was a speciality of Kusatsu-juku. The tea house was so named by Tokugawa Ieyasu after he stopped here following his victory at the Battle of Sekigahara and was presented with a rice cake by proprietor, a 84-year old former wet nurse of the Sasaki clan who had escaped the destruction of her clan at the hands of Oda Nobunaga. Afterwards, the tea house was mentioned by Matsuo Basho, Yosa Buson and other noted travelers. In front of the tea house, on the highway itself, a passenger in an open kago (palanquin) holds on to a rope as the porters rush to his destination, while a larger, covered kago, presumably for a high status passenger, heads in the opposite direction.

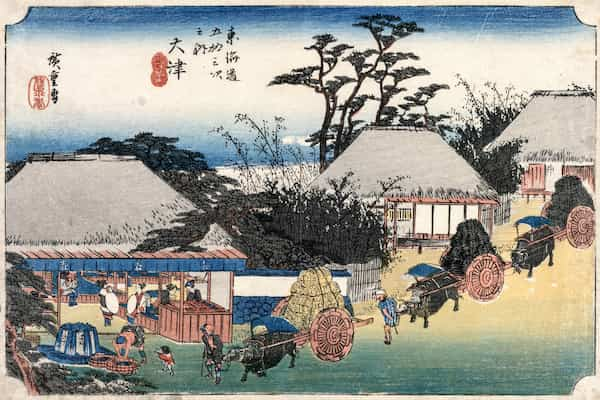

53rd station : Otsu 大津

Utagawa Hiroshige's ukiyo-e Hōeidō edition print of Ōtsu-juku dates from 1833 -1834. The print again depicts oxcarts, heavily laden with bushels of rice or charcoal, but this time descending the street. The oxcarts pass in front of the open front of the Hashirii teahouse, which was a popular resting point on the highway, and which served Hashirii Mochi (走り井餅), sweet rice cake which remains a local specialty of Ōtsu to this day. In front of the teahouse is a well from which fresh water gushes out. The Hashirii teahouse survived to the early Meiji period, and was later purchased for use as a villa by the nihonga painter Hashimoto Kansetsu in 1915. After his death, it became a Bushiest temple called Gesshin-ji. It is located between Oiwake Station and Ōtani Station on the Keihan Keishin Line.

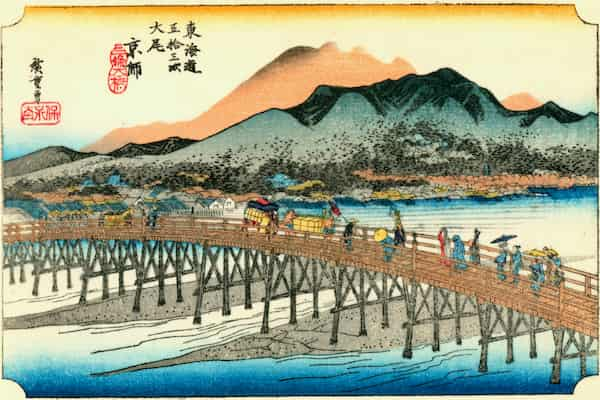

The end of the Tōkaidō: arriving at Kyoto 京師

Sanjō Ōhashi (三条大橋) is a bridge in Kyoto, Kyoto Prefecture, Japan. It spans the Kamo River as part of Sanjō-dōri (三条通り Third Avenue). It is well known because it served as the ending location for journeying on both the Nakasendō and the Tōkaidō; these were two of the famous "Five Routes" for long distance travelers during the Edo period in Japan's past.