The Denial of Saint Peter, Caravaggio

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, known as simply Caravaggio (29 September 1571 – 18 July 1610), was an Italian painter active in Rome for most of his artistic life. During the final four years of his life he moved between Naples, Malta, and Sicily until his death. His paintings have been characterized by art critics as combining a realistic observation of the human state, both physical and emotional, with a dramatic use of lighting, which had a formative influence on Baroque painting. Caravaggio employed close physical observation with a dramatic use of chiaroscuro that came to be known as tenebrism. He made the technique a dominant stylistic element, transfixing subjects in bright shafts of light and darkening shadows. Caravaggio vividly expressed crucial moments and scenes, often featuring violent struggles, torture, and death. He worked rapidly with live models, preferring to forgo drawings and work directly onto the canvas. His inspiring effect on the new Baroque style that emerged from Mannerism was profound. His influence can be seen directly or indirectly in the work of Peter Paul Rubens, Jusepe de Ribera, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and Rembrandt. Artists heavily under his influence were called the "Caravaggisti" (or "Caravagesques"), as well as tenebrists or tenebrosi ("shadowists"). Caravaggio trained as a painter in Milan before moving to Rome when he was in his twenties. He developed a considerable name as an artist and as a violent, touchy and provocative man. A brawl led to a death sentence for murder and forced him to flee to Naples. There he again established himself as one of the most prominent Italian painters of his generation. He travelled to Malta and on to Sicily in 1607 and pursued a papal pardon for his sentence. In 1609 he returned to Naples, where he was involved in a violent clash; his face was disfigured, and rumours of his death circulated. Questions about his mental state arose from his erratic and bizarre behavior. He died in 1610 under uncertain circumstances while on his way from Naples to Rome. Reports stated that he died of a fever, but suggestions have been made that he was murdered or that he died of lead poisoning. Caravaggio's innovations inspired Baroque painting, but the latter incorporated the drama of his chiaroscuro without the psychological realism. The style evolved and fashions changed, and Caravaggio fell out of favour. In the 20th century, interest in his work revived, and his importance to the development of Western art was reevaluated. The 20th-century art historian André Berne-Joffroy [fr] stated: "What begins in the work of Caravaggio is, quite simply, modern painting."

Adoration of the Shepherds, Caravaggio

Caravaggio- Early Career

Caravaggio was born in Milan, where his father, Fermo (Fermo Merixio), was a household administrator and architect-decorator to the Marchese of Caravaggio, a town 35 km to the east of Milan and south of Bergamo. In 1576 the family moved to Caravaggio (Caravaggius) to escape a plague that ravaged Milan, and Caravaggio's father and grandfather both died there on the same day in 1577. It is assumed that the artist grew up in Caravaggio, but his family kept up connections with the Sforzas and the powerful Colonna family, who were allied by marriage with the Sforzas and destined to play a major role later in Caravaggio's life. Caravaggio's mother had to raise all of her five children in poverty. She later died in 1584, the same year he began his four-year apprenticeship to the Milanese painter Simone Peterzano, described in the contract of apprenticeship as a pupil of Titian. Caravaggio appears to have stayed in the Milan-Caravaggio area after his apprenticeship ended, but it is possible that he visited Venice and saw the works of Giorgione, whom Federico Zuccari later accused him of imitating, and Titian. He would also have become familiar with the art treasures of Milan, including Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper, and with the regional Lombard art, a style that valued simplicity and attention to naturalistic detail and was closer to the naturalism of Germany than to the stylised formality and grandeur of Roman Mannerism.

Annunciation, Caravaggio

Cardsharps, Caravaggio

Bacchus, Caravaggio

Crucifixion of Saint Peter, Caravaggio

Caravaggio in Rome

Following his initial training under Simone Peterzano, in 1592, Caravaggio left Milan for Rome in flight after "certain quarrels" and the wounding of a police officer. The young artist arrived in Rome "naked and extremely needy... without fixed address and without provision... short of money." During this period, he stayed with the miserly Pandolfo Pucci, known as "monsignor Insalata". A few months later he was performing hack-work for the highly successful Giuseppe Cesari, Pope Clement VIII's favourite artist, "painting flowers and fruit" in his factory-like workshop. In Rome, there was a demand for paintings to fill the many huge new churches and palazzi being built at the time. It was also a period when the Church was searching for a stylistic alternative to Mannerism in religious art that was tasked to counter the threat of Protestantism. Caravaggio's innovation was a radical naturalism that combined close physical observation with a dramatic, even theatrical, use of chiaroscuro that came to be known as tenebrism (the shift from light to dark with little intermediate value).

Known works from this period include a small Boy Peeling a Fruit (his earliest known painting), a Boy with a Basket of Fruit, and the Young Sick Bacchus, supposedly a self-portrait done during convalescence from a serious illness that ended his employment with Cesari. All three demonstrate the physical particularity for which Caravaggio was to become renowned: the fruit-basket-boy's produce has been analysed by a professor of horticulture, who was able to identify individual cultivars right down to "...a large fig leaf with a prominent fungal scorch lesion resembling anthracnose (Glomerella cingulata)." Caravaggio left Cesari, determined to make his own way after a heated argument. At this point he forged some extremely important friendships, with the painter Prospero Orsi, the architect Onorio Longhi, and the sixteen-year-old Sicilian artist Mario Minniti. Orsi, established in the profession, introduced him to influential collectors; Longhi, more balefully, introduced him to the world of Roman street brawls. Minniti served Caravaggio as a model and, years later, would be instrumental in helping him to obtain important commissions in Sicily. Ostensibly, the first archival reference to Caravaggio in a contemporary document from Rome is the listing of his name, with that of Prospero Orsi as his partner, as an 'assistant' in a procession in October 1594 in honour of St. Luke. The earliest informative account of his life in the city is a court transcript dated 11 July 1597, when Caravaggio and Prospero Orsi were witnesses to a crime near San Luigi de' Francesi.

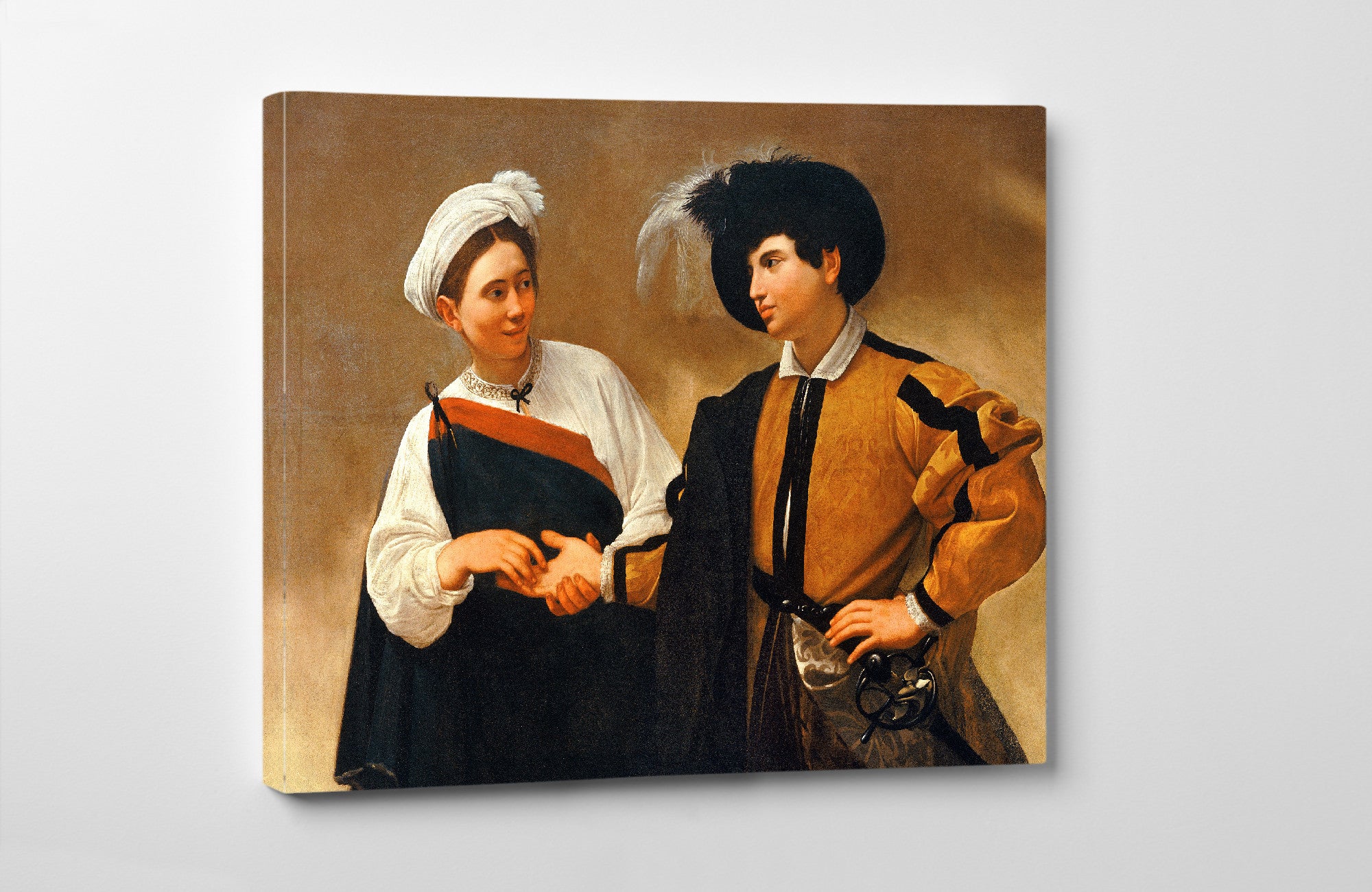

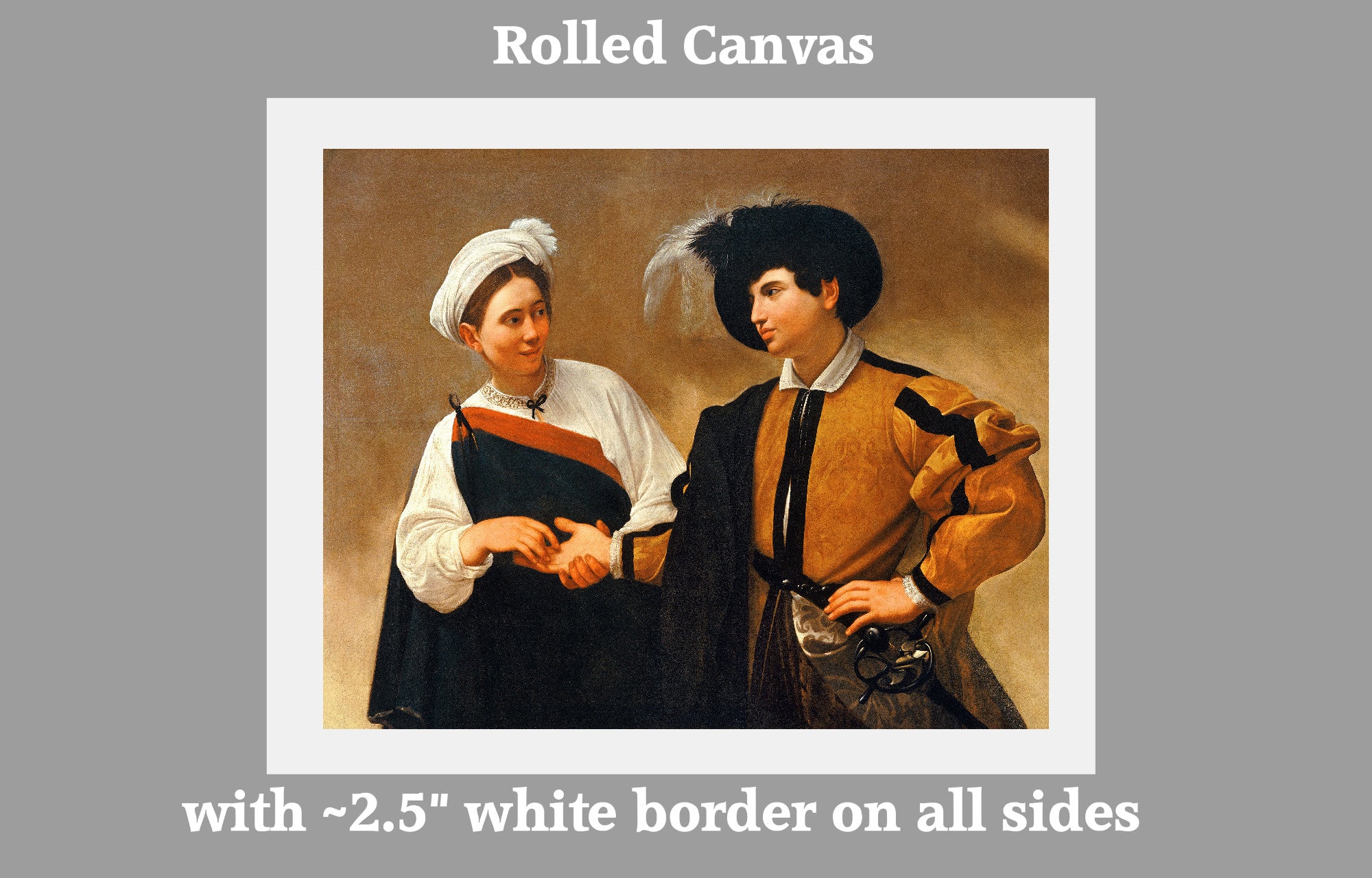

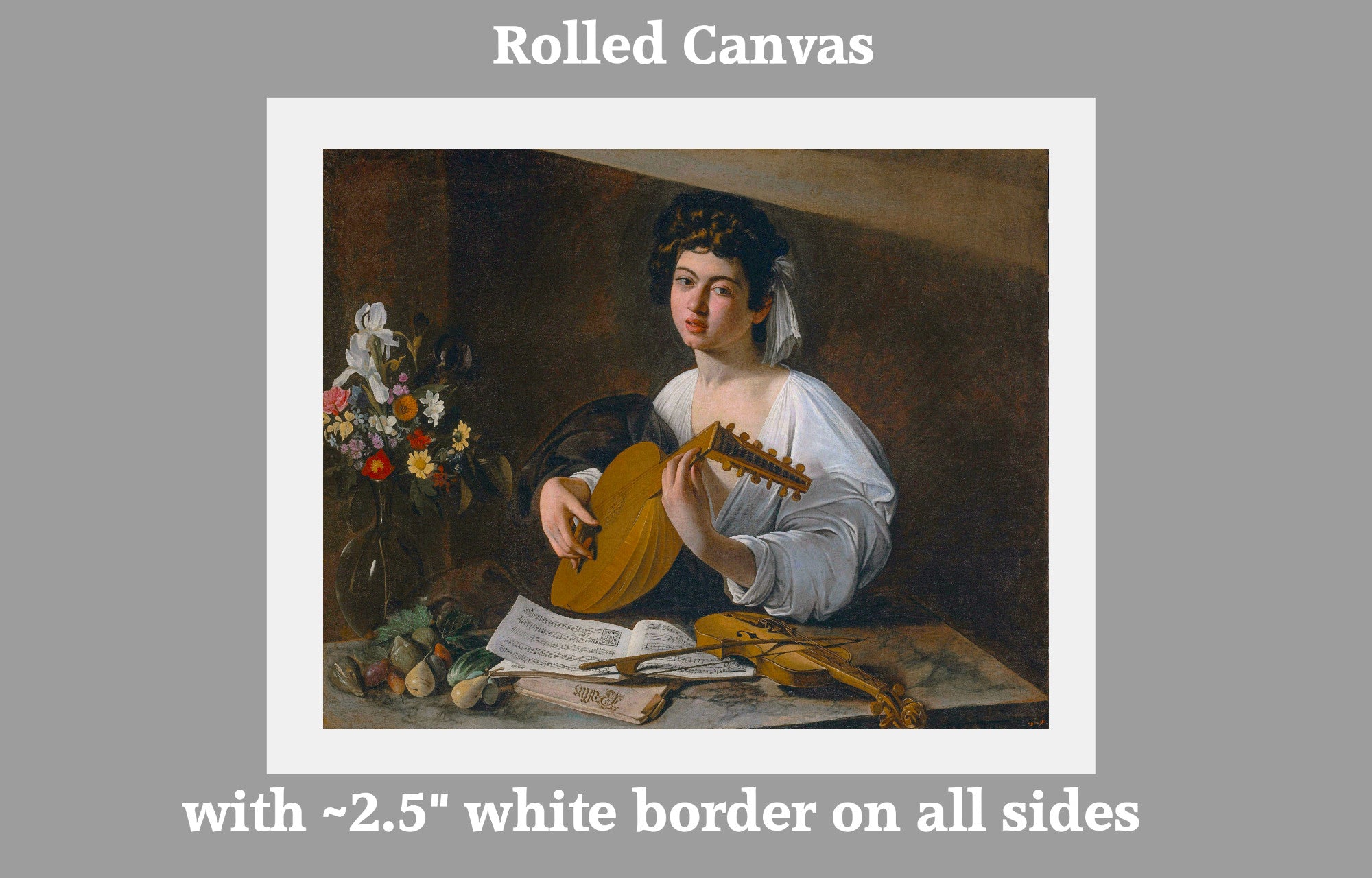

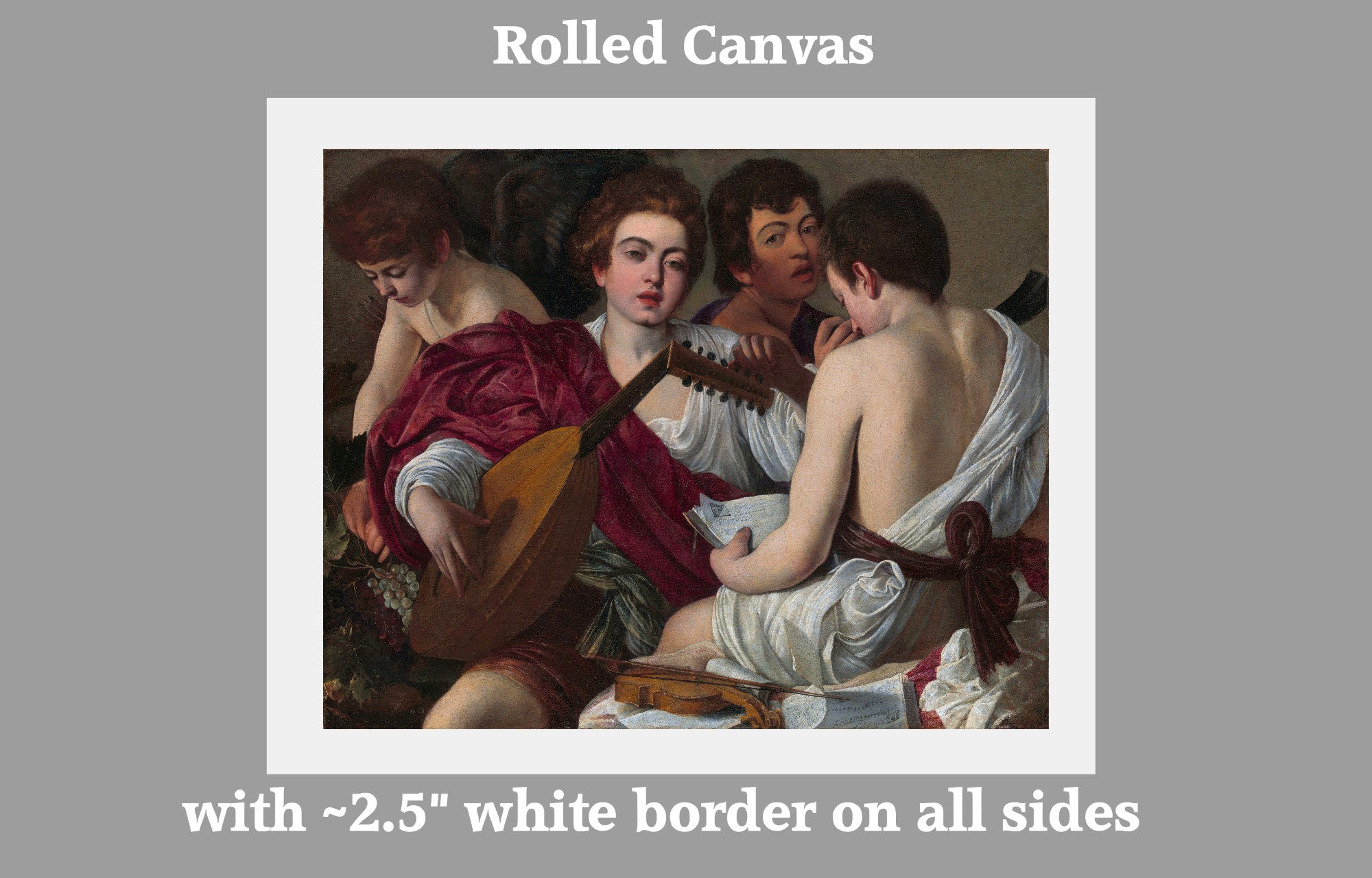

The Fortune Teller, his first composition with more than one figure, shows a boy, likely Minniti, having his palm read by a Romani girl, who is stealthily removing his ring as she strokes his hand. The theme was quite new for Rome and proved immensely influential over the next century and beyond. However, at the time, Caravaggio sold it for practically nothing. The Cardsharps—showing another naïve youth of privilege falling the victim of card cheats—is even more psychologically complex and perhaps Caravaggio's first true masterpiece. Like The Fortune Teller, it was immensely popular, and over 50 copies survived. More importantly, it attracted the patronage of Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, one of the leading connoisseurs in Rome. For Del Monte and his wealthy art-loving circle, Caravaggio executed a number of intimate chamber-pieces—The Musicians, The Lute Player, a tipsy Bacchus, an allegorical but realistic Boy Bitten by a Lizard—featuring Minniti and other adolescent models.

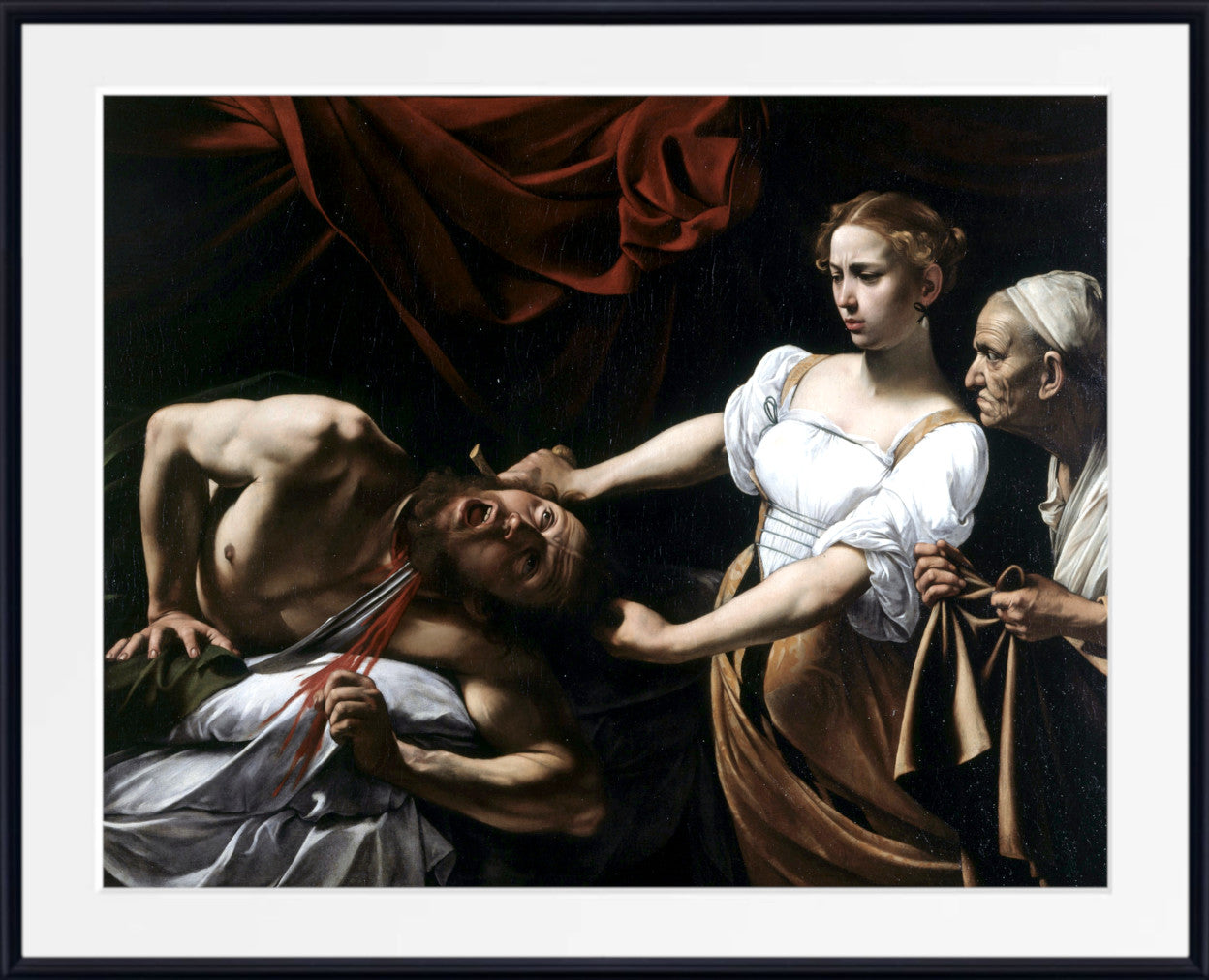

Caravaggio's first paintings on religious themes returned to realism and the emergence of remarkable spirituality. The first of these was the Penitent Magdalene, showing Mary Magdalene at the moment when she has turned from her life as a courtesan and sits weeping on the floor, her jewels scattered around her. "It seemed not a religious painting at all ... a girl sitting on a low wooden stool drying her hair ... Where was the repentance ... suffering ... promise of salvation?" It was understated, in the Lombard manner, not histrionic in the Roman manner of the time. It was followed by others in the same style: Saint Catherine; Martha and Mary Magdalene; Judith Beheading Holofernes; a Sacrifice of Isaac; a Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy; and a Rest on the Flight into Egypt. These works, while viewed by a comparatively limited circle, increased Caravaggio's fame with both connoisseurs and his fellow artists. But a true reputation would depend on public commissions, for which it was necessary to look to the Church.

Already evident was the intense realism or naturalism for which Caravaggio is now famous. He preferred to paint his subjects as the eye sees them, with all their natural flaws and defects, instead of as idealised creations. This allowed a full display of his virtuosic talents. This shift from accepted standard practice and the classical idealism of Michelangelo was very controversial at the time. Caravaggio also dispensed with the lengthy preparations traditional in central Italy at the time. Instead, he preferred the Venetian practice of working in oils directly from the subject—half-length figures and still life. Supper at Emmaus, from c. 1600–1601, is a characteristic work of this period demonstrating his virtuoso talent.

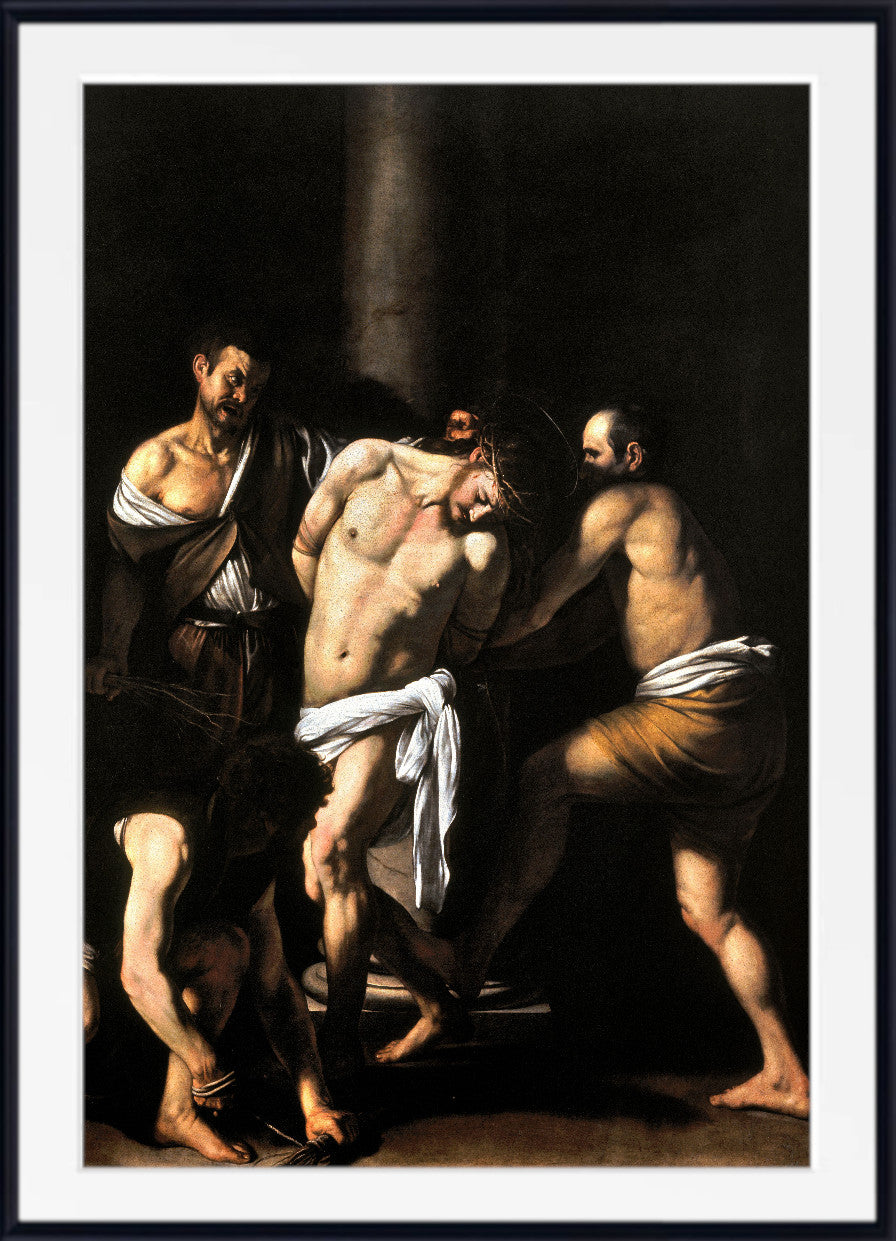

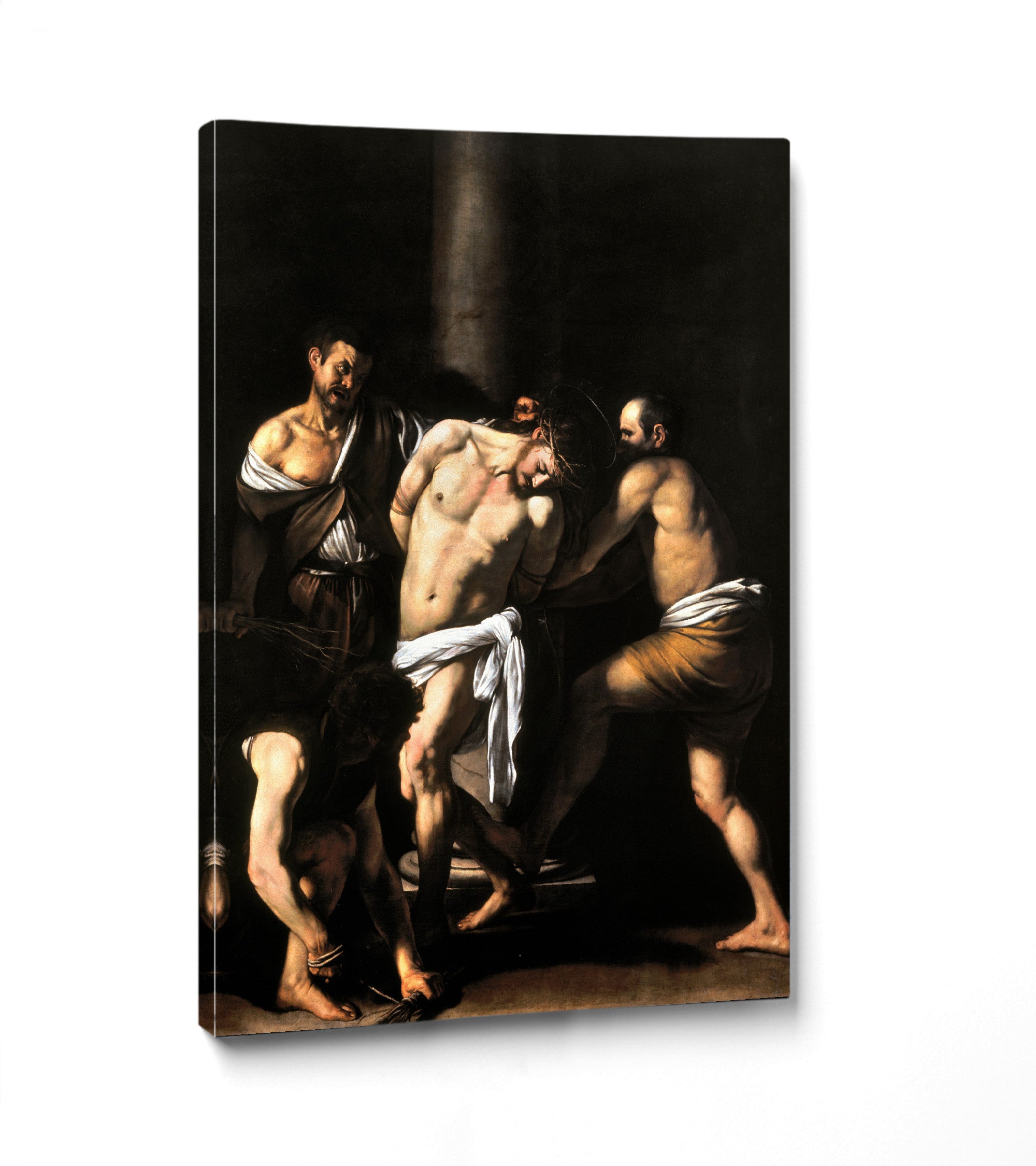

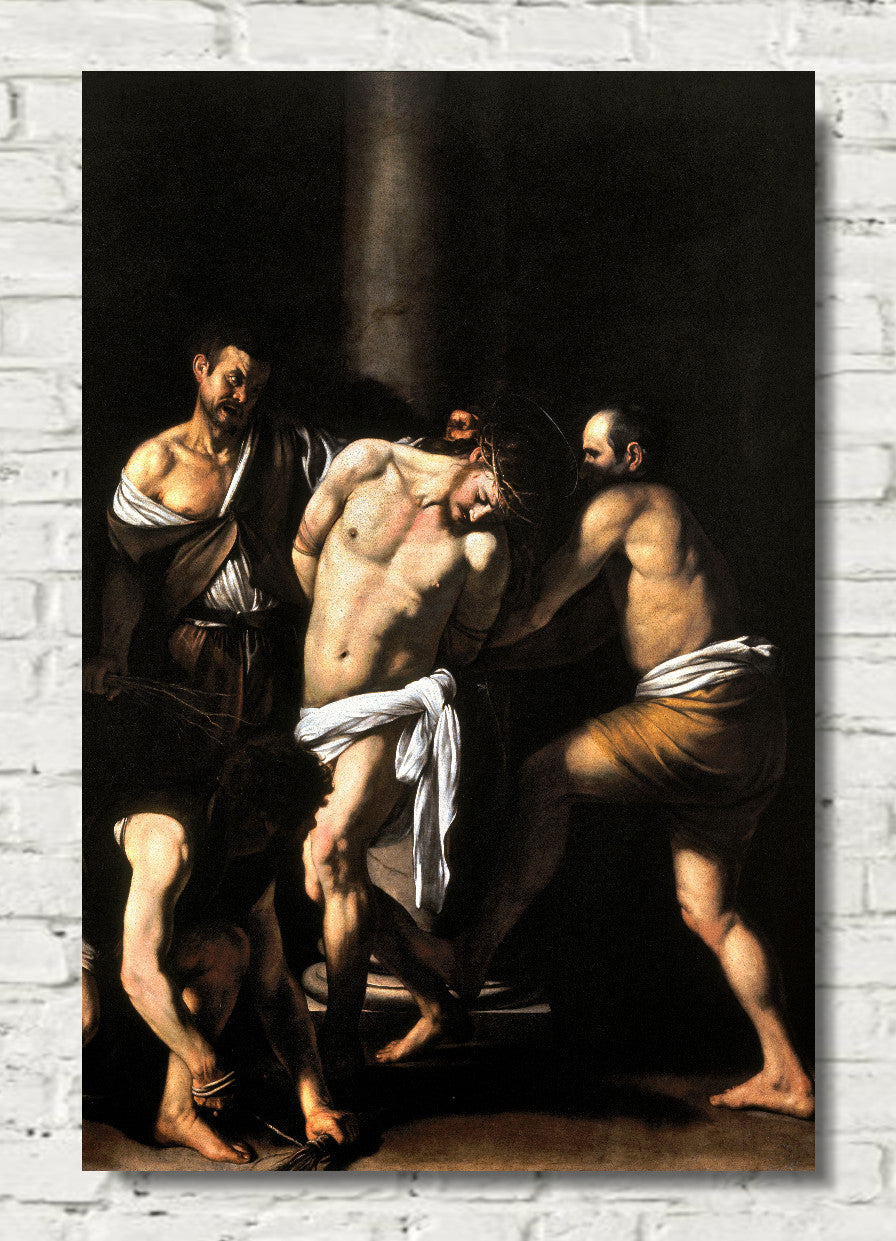

Christ at the Column, Caravaggio

David with the Head of Goliath, Caravaggio

Incredulity of Saint Thomas, Caravaggio

Judith Beheading Holofernes, Caravaggio

Jupiter, Neptune and Pluto, Caravaggio

Madonna of the Rosary, Caravaggio

Caravaggio - Success in Rome

In 1599, presumably through the influence of Del Monte, Caravaggio was contracted to decorate the Contarelli Chapel in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi. The two works making up the commission, The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew and The Calling of Saint Matthew, delivered in 1600, were an immediate sensation. Thereafter he never lacked commissions or patrons.

Caravaggio's tenebrism (a heightened chiaroscuro) brought high drama to his subjects, while his acutely observed realism brought a new level of emotional intensity. Opinion among his artist peers was polarised. Some denounced him for various perceived failings, notably his insistence on painting from life, without drawings, but for the most part, he was hailed as a great artistic visionary: "The painters then in Rome were greatly taken by this novelty, and the young ones particularly gathered around him, praised him as the unique imitator of nature, and looked on his work as miracles." Caravaggio went on to secure a string of prestigious commissions for religious works featuring violent struggles, grotesque decapitations, torture and death. Most notable and technically masterful among them were The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (circa 1601) and The Taking of Christ (circa 1602) for the Mattei family, which were only rediscovered in the 1990s in Trieste and in Dublin after remaining unrecognised for two centuries. For the most part, each new painting increased his fame, but a few were rejected by the various bodies for whom they were intended, at least in their original forms, and had to be re-painted or found new buyers. The essence of the problem was that while Caravaggio's dramatic intensity was appreciated, his realism was seen by some as unacceptably vulgar.

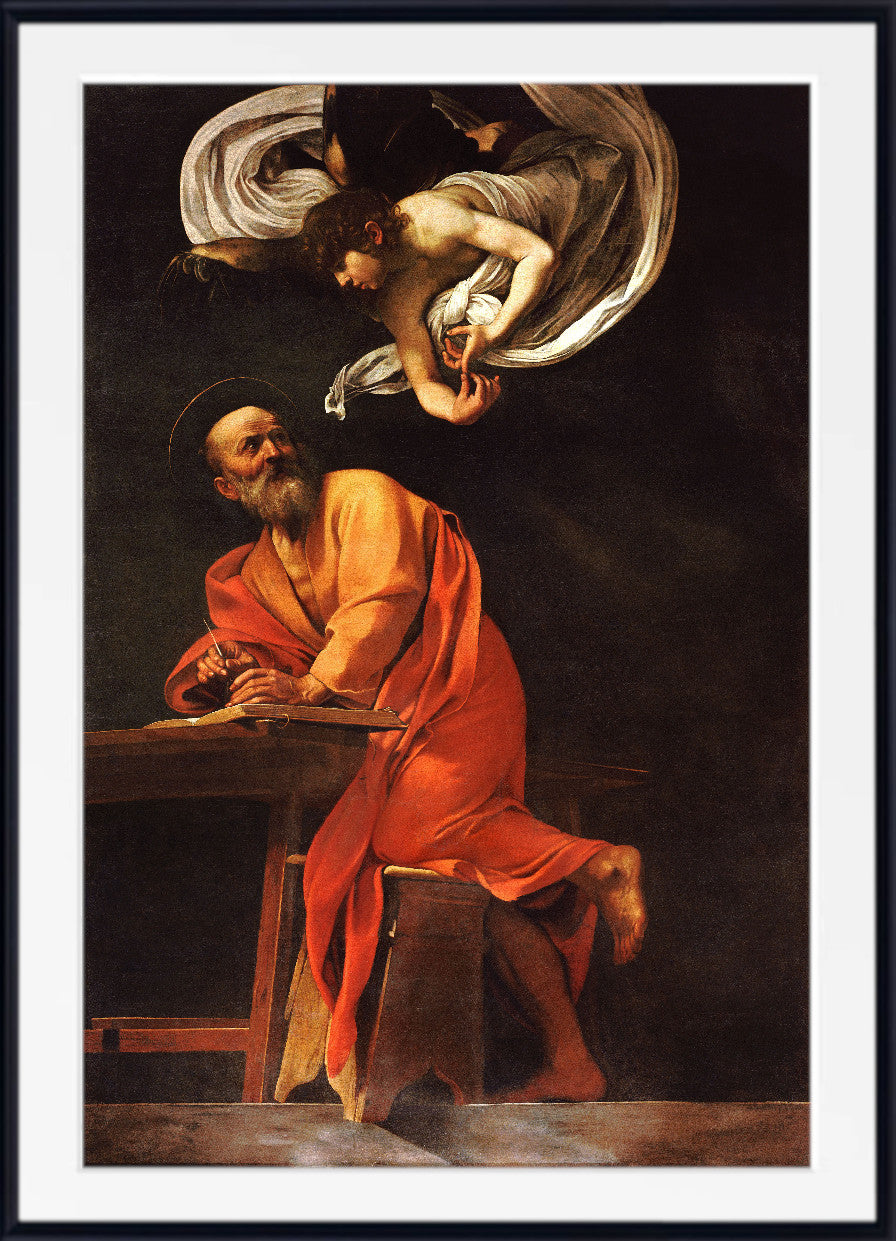

His first version of Saint Matthew and the Angel, featuring the saint as a bald peasant with dirty legs attended by a lightly clad over-familiar boy-angel, was rejected and a second version had to be painted as The Inspiration of Saint Matthew. Similarly, The Conversion of Saint Paul was rejected, and while another version of the same subject, the Conversion on the Way to Damascus, was accepted, it featured the saint's horse's haunches far more prominently than the saint himself, prompting this exchange between the artist and an exasperated official of Santa Maria del Popolo: "Why have you put a horse in the middle, and Saint Paul on the ground?" "Because!" "Is the horse God?" "No, but he stands in God's light!" The aristocratic collector Ciriaco Mattei, brother of Cardinal Girolamo Mattei, who was friends with Cardinal Francesco Maria Bourbon Del Monte, gave The Supper at Emmaus for the city palace he shared with his brother, 1601 (National Gallery, London), The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, c. 1601, "Ecclesiastical Version" (Private Collection, Florence), The Incredulity of Saint Thomas c. 1601, 1601 "Secular Version" (Sanssouci Palace, Potsdam), John the Baptist with the Ram, 1602 (Capitoline Museums, Rome) and The Taking of Christ, 1602 (National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin) Caravaggio commissioned. The second version of The Taking of Christ, which was looted from the Odessa Museum in 2008 and recovered in 2010, is believed by some experts to be a contemporary copy.

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas is one of the most famous paintings by the italian baroque master Caravaggio, circa 1601-1602. There are two autograph versions of Caravaggio's „The Incredulity of Saint Thomas“, an ecclesiastical "Trieste" version for Girolamo Mattei now in a private collection and a secular "Potsdam" version for Vincenzo Giustiniani (Pietro Bellori) and later entered the Prussian Royal Collection and survived the Second World War unscathed and can be admired in the Palais in Sanssouci, Potsdam. It depicts the episode that led to the term "Doubting Thomas", officially known as "The Incredulity of Saint Thomas", which has been frequently depicted and used to make various theological statements in Christian art since at least the 5th century. According to the Gospel of John, Thomas the Apostle missed one of Jesus' appearances to the apostles after his resurrection and said, "Unless I see the marks of the nails in his hands, and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe it." A week later, Jesus appeared and told Thomas to touch him and stop doubting. Then Jesus said, "Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed." The two pictures show in a demonstrative gesture how the doubting apostle puts his finger into christ's side wound, the latter guiding his hand. The unbeliever is depicted like a peasant, dressed in a robe torn at the shoulder and with dirt under his fingernails. The composition of the picture is designed in such a way that the viewer is directly involved in the event and feels the intensity of the event as it were. It should also be noted that in the ecclesiastical version of the unbelieving Thomas, Christ's thigh is shown to be covered, whereas in the secular version of the painting, Christ's thigh is visible.

The Death of the Virgin, commissioned in 1601 by a wealthy jurist for his private chapel in the new Carmelite church of Santa Maria della Scala, was rejected by the Carmelites in 1606. Caravaggio's contemporary Giulio Mancini records that it was rejected because Caravaggio had used a well-known prostitute as his model for the Virgin. Giovanni Baglione, another contemporary, tells that it was due to Mary's bare legs—a matter of decorum in either case. Caravaggio scholar John Gash suggests that the problem for the Carmelites may have been theological rather than aesthetic, in that Caravaggio's version fails to assert the doctrine of the Assumption of Mary, the idea that the Mother of God did not die in any ordinary sense but was assumed into Heaven. The replacement altarpiece commissioned (from one of Caravaggio's most able followers, Carlo Saraceni), showed the Virgin not dead, as Caravaggio had painted her, but seated and dying; and even this was rejected, and replaced with a work showing the Virgin not dying, but ascending into Heaven with choirs of angels. In any case, the rejection did not mean that Caravaggio or his paintings were out of favour. The Death of the Virgin was no sooner taken out of the church than it was purchased by the Duke of Mantua, on the advice of Rubens, and later acquired by Charles I of England before entering the French royal collection in 1671. One secular piece from these years is Amor Vincit Omnia, in English also called Amor Victorious, painted in 1602 for Vincenzo Giustiniani, a member of Del Monte's circle. The model was named in a memoir of the early 17th century as "Cecco", the diminutive for Francesco. He is possibly Francesco Boneri, identified with an artist active in the period 1610–1625 and known as Cecco del Caravaggio ('Caravaggio's Cecco'), carrying a bow and arrows and trampling symbols of the warlike and peaceful arts and sciences underfoot. He is unclothed, and it is difficult to accept this grinning urchin as the Roman god Cupid—as difficult as it was to accept Caravaggio's other semi-clad adolescents as the various angels he painted in his canvases, wearing much the same stage-prop wings. The point, however, is the intense yet ambiguous reality of the work: it is simultaneously Cupid and Cecco, as Caravaggio's Virgins were simultaneously the Mother of Christ and the Roman courtesans who modeled for them.

Caravaggio - Murder in Rome

Caravaggio led a tumultuous life. He was notorious for brawling, even in a time and place when such behavior was commonplace, and the transcripts of his police records and trial proceedings fill many pages. Bellori claims that around 1590–1592, Caravaggio, already well known for brawling with gangs of young men, committed a murder which forced him to flee from Milan, first to Venice and then to Rome. On 28 November 1600, while living at the Palazzo Madama with his patron Cardinal Del Monte, Caravaggio beat nobleman Girolamo Stampa da Montepulciano, a guest of the cardinal, with a club, resulting in an official complaint to the police. Episodes of brawling, violence, and tumult grew more and more frequent. Caravaggio was often arrested and jailed at Tor di Nona. After his release from jail in 1601, Caravaggio returned to paint first The Taking of Christ and then Amor Vincit Omnia. In 1603, he was arrested again, this time for the defamation of another painter, Giovanni Baglione, who sued Caravaggio and his followers Orazio Gentileschi and Onorio Longhi for writing offensive poems about him. The French ambassador intervened, and Caravaggio was transferred to house arrest after a month in jail in Tor di Nona. Between May and October 1604, Caravaggio was arrested several times for possession of illegal weapons and for insulting the city guards. He was also sued by a tavern waiter for having thrown a plate of artichokes in his face. An early published notice on Caravaggio, dating from 1604 and describing his lifestyle three years previously, recounts that "after a fortnight's work he will swagger about for a month or two with a sword at his side and a servant following him, from one ball-court to the next, ever ready to engage in a fight or an argument, so that it is most awkward to get along with him." In 1605, Caravaggio was forced to flee to Genoa for three weeks after seriously injuring Mariano Pasqualone di Accumoli, a notary, in a dispute over Lena, Caravaggio's model and lover. The notary reported having been attacked on 29 July with a sword, causing a severe head injury. Caravaggio's patrons intervened and managed to cover up the incident. Upon his return to Rome, Caravaggio was sued by his landlady Prudenzia Bruni for not having paid his rent. Out of spite, Caravaggio threw rocks through her window at night and was sued again. In November, Caravaggio was hospitalized for an injury which he claimed he had caused himself by falling on his own sword. On 29 May 1606, Caravaggio killed a young man, possibly unintentionally, resulting in him fleeing Rome with a death sentence hanging over him. Ranuccio Tommasoni was a gangster from a wealthy family. The two had argued many times, often ending in blows. The circumstances are unclear, whether a brawl or a duel with swords at Campo Marzio, but the killing may have been unintentional. Many rumors circulated at the time as to the cause of the fight. Several contemporary avvisi referred to a quarrel over a gambling debt and a pallacorda game, a sort of tennis, and this explanation has become established in the popular imagination. Other rumors, however, claimed that the duel stemmed from jealousy over Fillide Melandroni, a well-known Roman prostitute who had modeled for him in several important paintings; Tommasoni was her pimp. According to such rumors, Caravaggio castrated Tommasoni with his sword before deliberately killing him, with other versions claiming that Tommasoni's death was caused accidentally during the castration. The duel may have had a political dimension, as Tommasoni's family was notoriously pro-Spanish, while Caravaggio was a client of the French ambassador. Caravaggio's patrons had hitherto been able to shield him from any serious consequences of his frequent duels and brawling, but Tommasoni's wealthy family was outraged by his death and demanded justice. Caravaggio's patrons were unable to protect him. Caravaggio was sentenced to beheading for murder, and an open bounty was decreed, enabling anyone who recognized him to legally carry the sentence out. Caravaggio's paintings began to obsessively depict severed heads, often his own, at this time. Good modern accounts are to be found in Peter Robb's M and Helen Langdon's Caravaggio: A Life. A theory relating the death to Renaissance notions of honour and symbolic wounding has been advanced by art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon. Whatever the details, it was a serious matter.

Caravaggio was forced to flee Rome. He moved just south of the city, then to Naples, Malta, and Sicily.

Sacrifice of Isaac, Caravaggio

Caravaggio - Naples

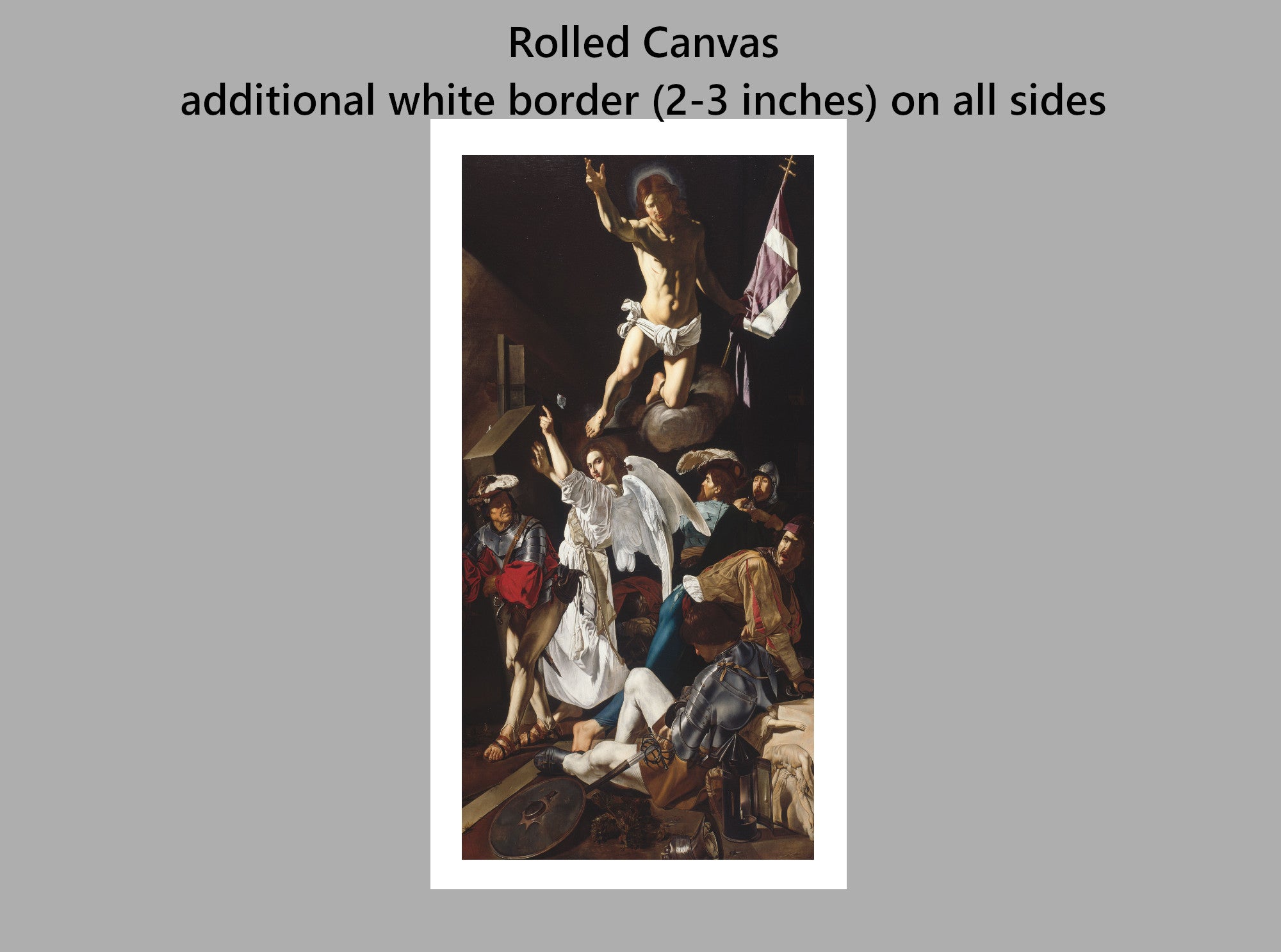

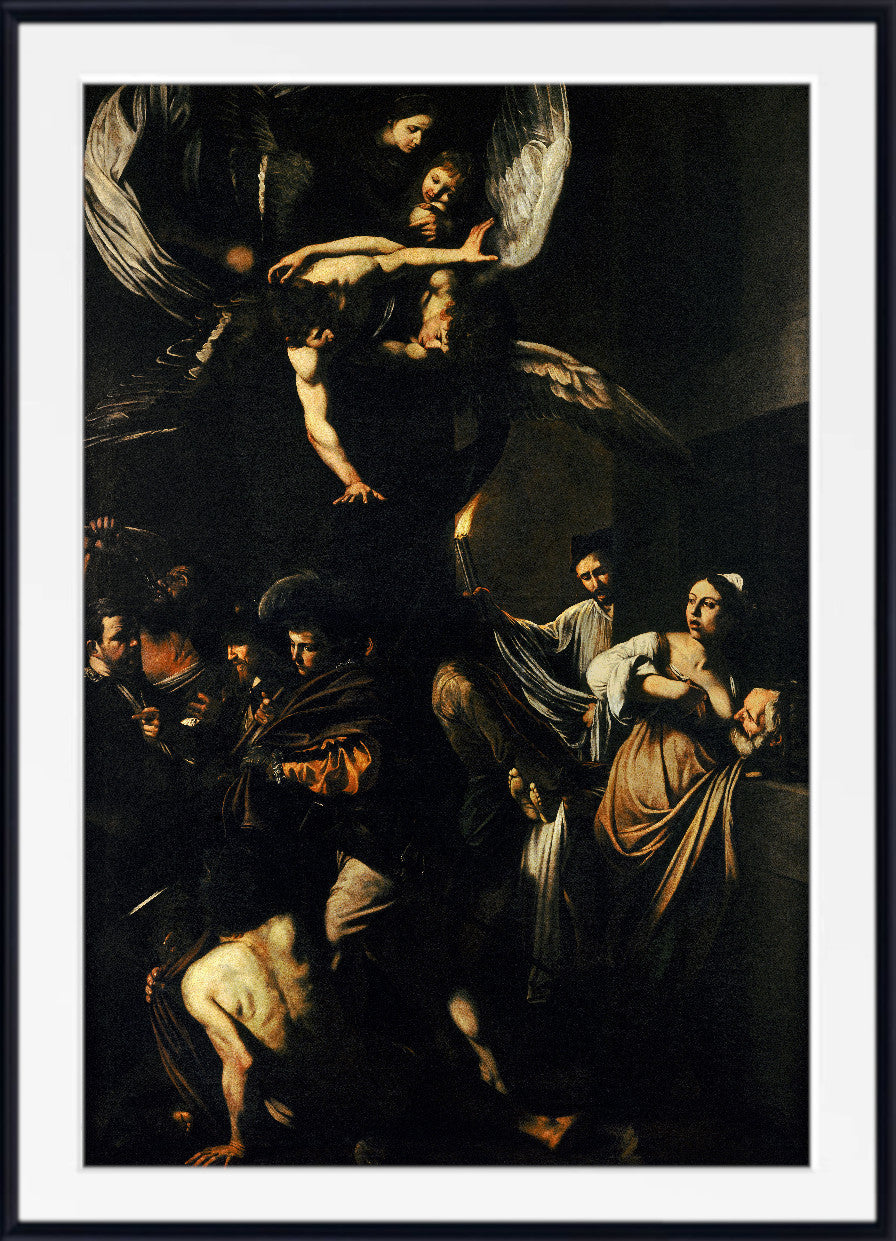

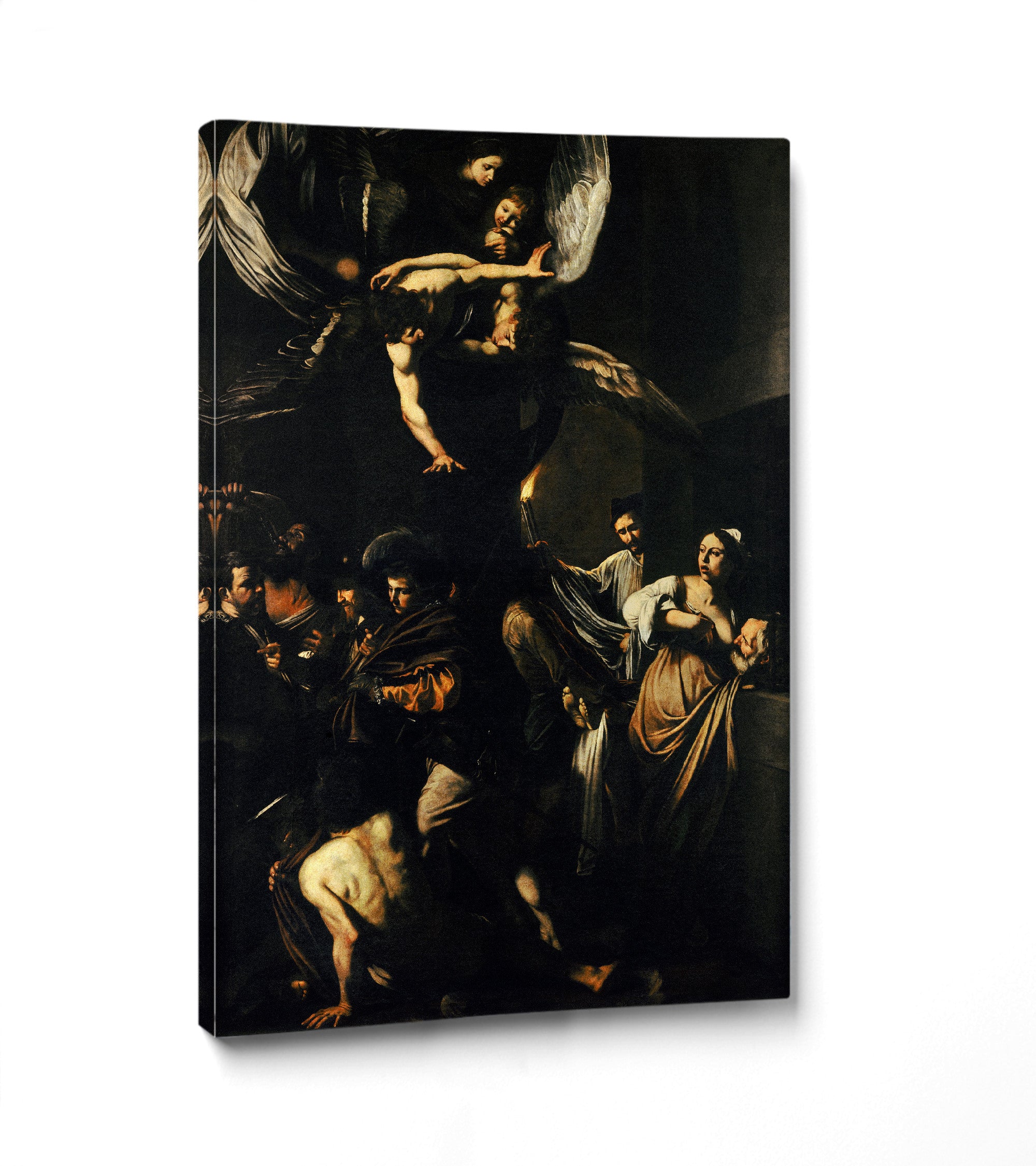

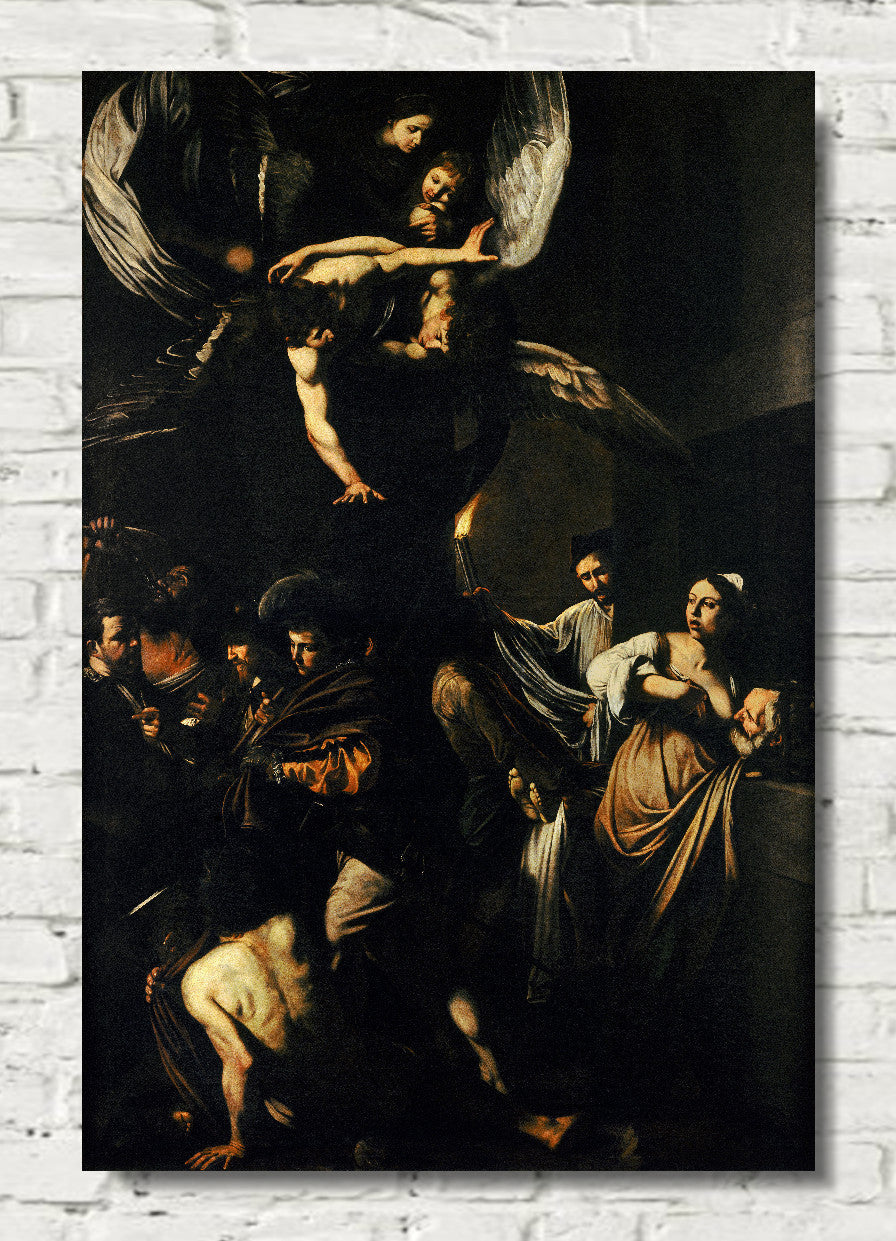

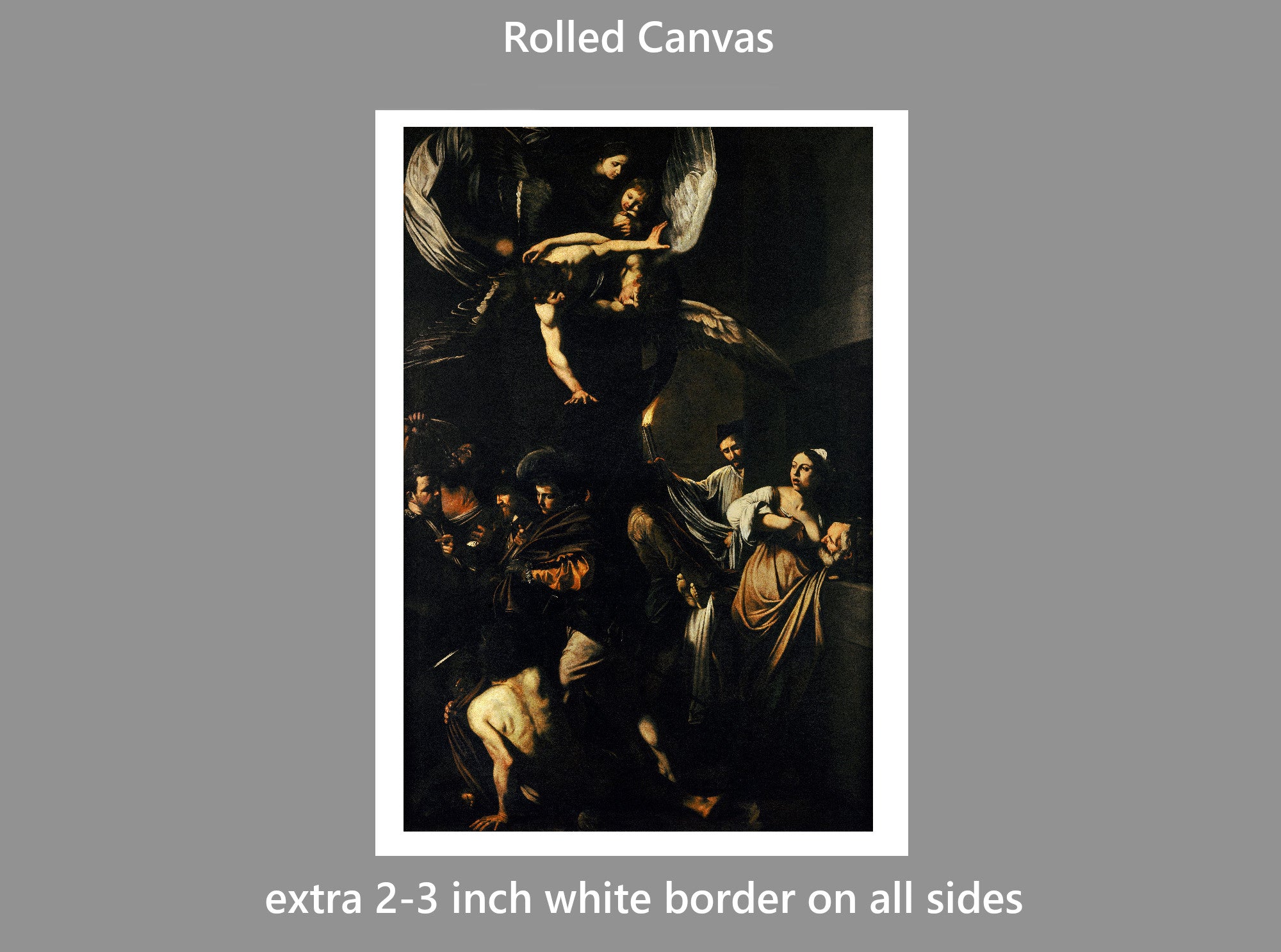

Following the death of Tomassoni, Caravaggio fled first to the estates of the Colonna family south of Rome, then on to Naples, where Costanza Colonna Sforza, widow of Francesco Sforza, in whose husband's household Caravaggio's father had held a position, maintained a palace. In Naples, outside the jurisdiction of the Roman authorities and protected by the Colonna family, the most famous painter in Rome became the most famous in Naples. The Seven Works of Mercy, 1606–1607, Pio Monte della Misericordia, Naples His connections with the Colonnas led to a stream of important church commissions, including the Madonna of the Rosary, and The Seven Works of Mercy. The Seven Works of Mercy depicts the seven corporal works of mercy as a set of compassionate acts concerning the material needs of others. The painting was made for and is still housed in the church of Pio Monte della Misericordia in Naples. Caravaggio combined all seven works of mercy in one composition, which became the church's altarpiece. Alessandro Giardino has also established the connection between the iconography of "The Seven Works of Mercy" and the cultural, scientific and philosophical circles of the painting's commissioners.

Caravaggio - Malta

Despite his success in Naples, after only a few months in the city Caravaggio left for Malta, the headquarters of the Knights of Malta. Fabrizio Sforza Colonna, Costanza's son, was a Knight of Malta and general of the Order's galleys. He appears to have facilitated Caravaggio's arrival on the island in 1607 (and his escape the next year). Caravaggio presumably hoped that the patronage of Alof de Wignacourt, Grand Master of the Knights of Saint John, could help him secure a pardon for Tomassoni's death. Wignacourt was so impressed at having the famous artist as official painter to the Order that he inducted him as a Knight, and the early biographer Bellori records that the artist was well pleased with his success.

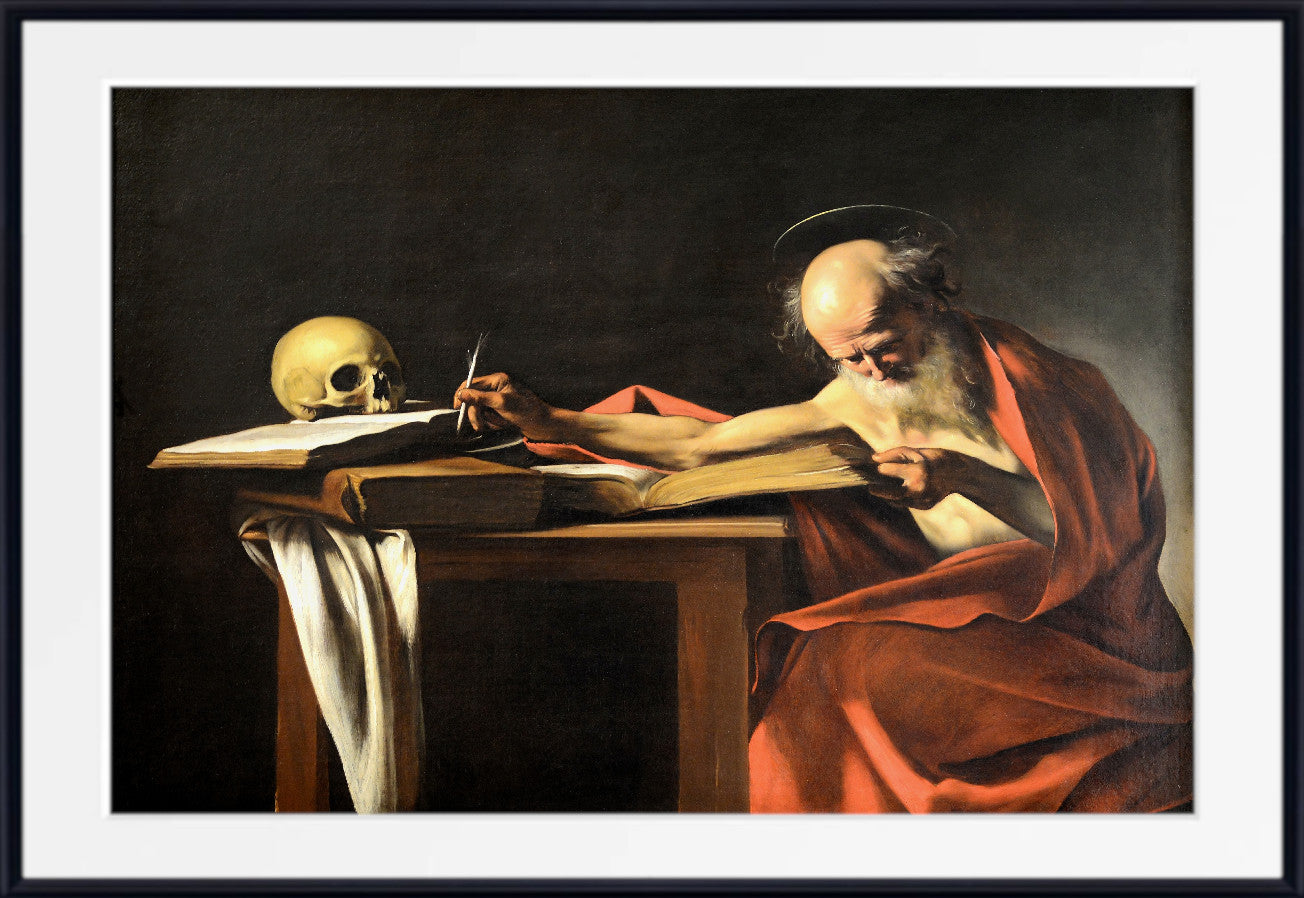

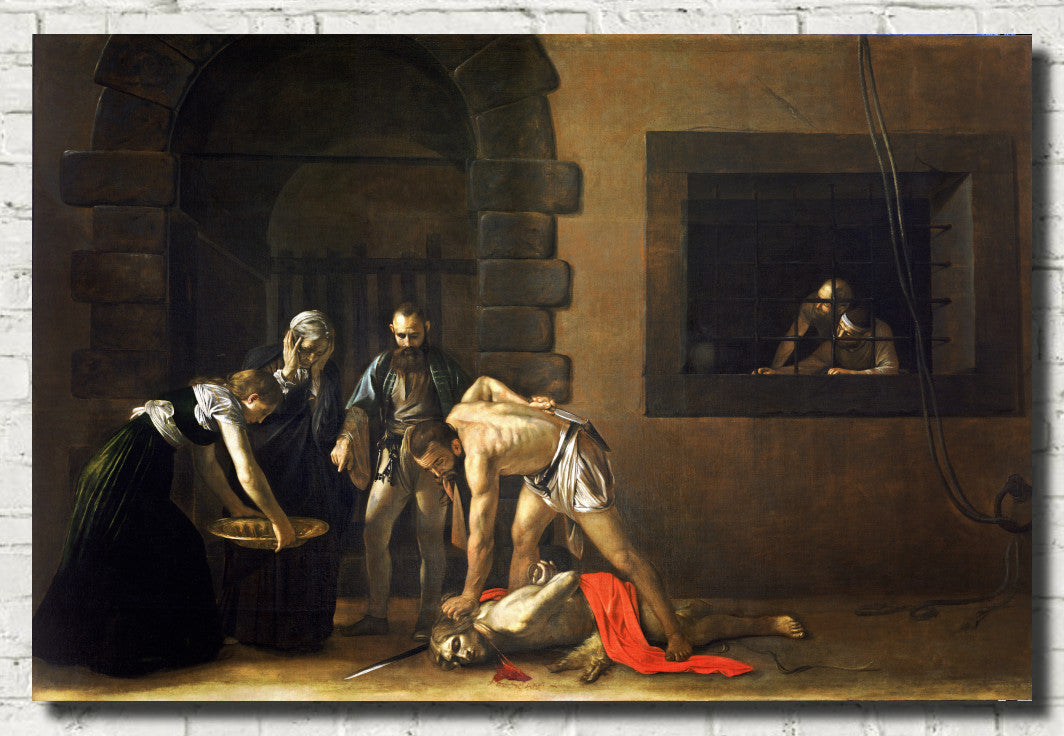

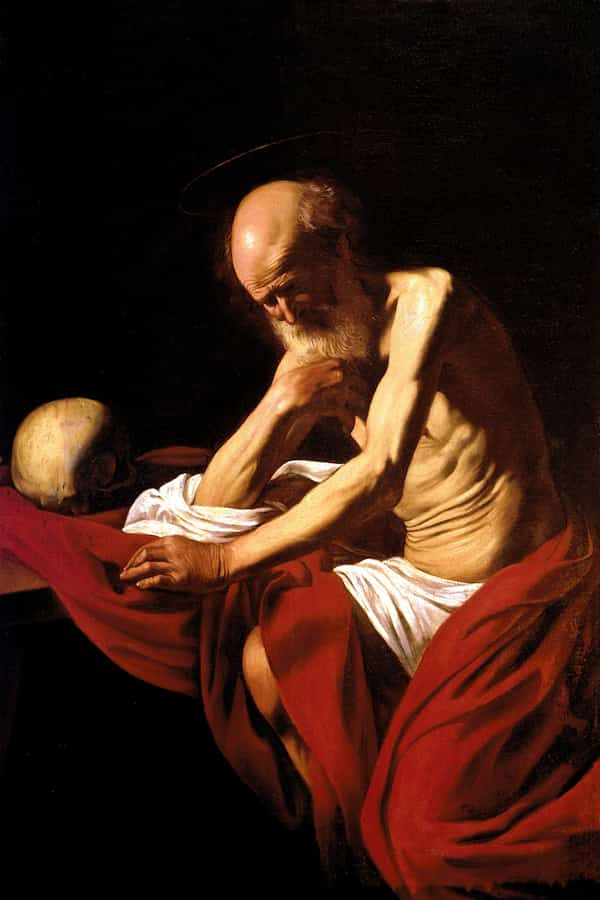

Major works from his Malta period include the Beheading of Saint John the Baptist, his largest ever work, and the only painting to which he put his signature, Saint Jerome Writing (both housed in Saint John's Co-Cathedral, Valletta, Malta) and a Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt and his Page, as well as portraits of other leading Knights. According to Andrea Pomella, The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist is widely considered "one of the most important works in Western painting." Completed in 1608, the painting had been commissioned by the Knights of Malta as an altarpiece and measuring 370 by 520 centimetres (150 in × 200 in) was the largest altarpiece Caravaggio painted. It still hangs in St. John's Co-Cathedral, for which it was commissioned and where Caravaggio himself was inducted and briefly served as a knight. Yet, by late August 1608, he was arrested and imprisoned, likely the result of yet another brawl, this time with an aristocratic knight, during which the door of a house was battered down and the knight seriously wounded. Caravaggio was imprisoned by the Knights at Valletta, but he managed to escape. By December, he had been expelled from the Order "as a foul and rotten member", a formal phrase used in all such cases.

Saint Jerome, Penitent, Caravaggio

Caravaggio - Sicily

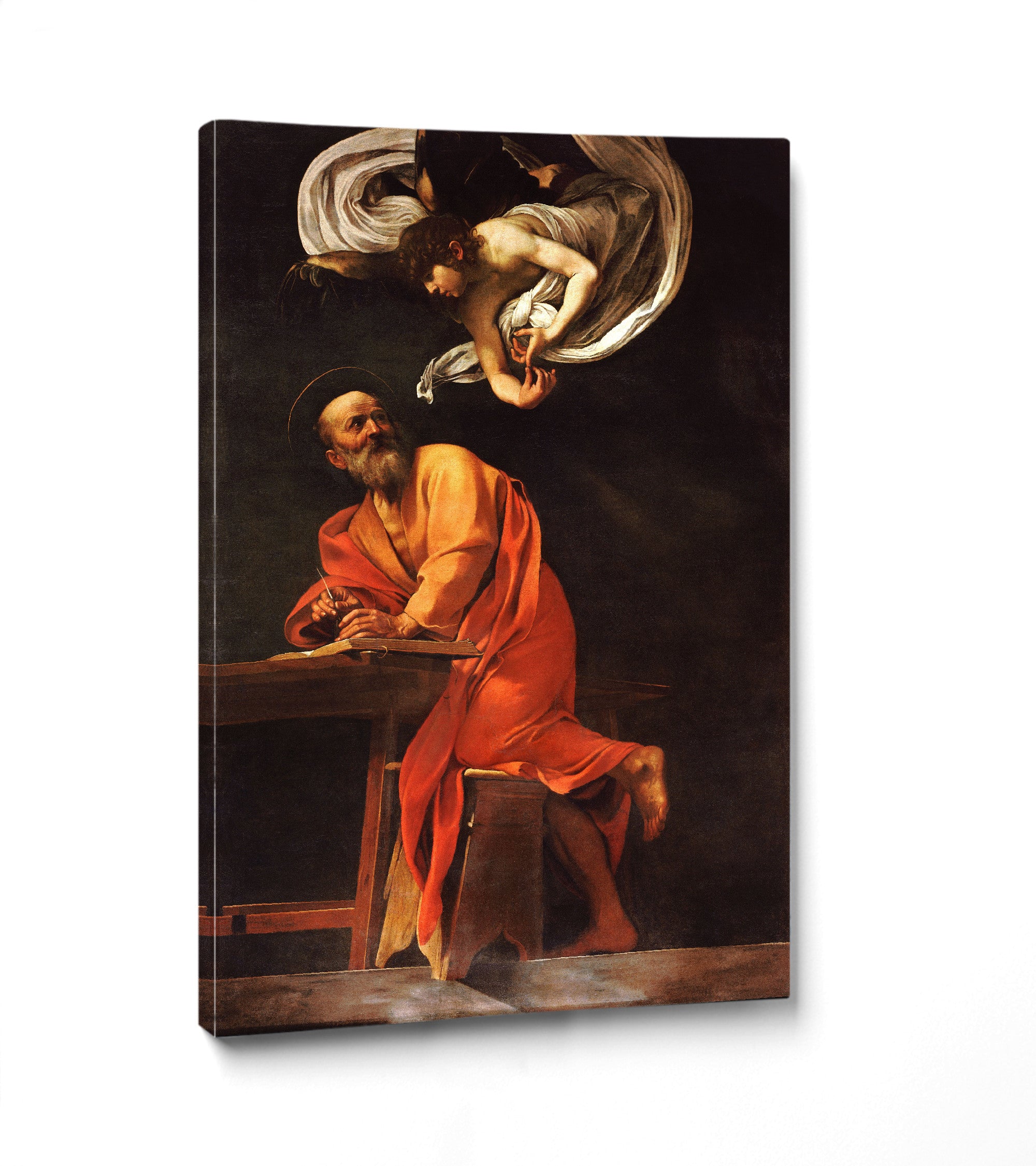

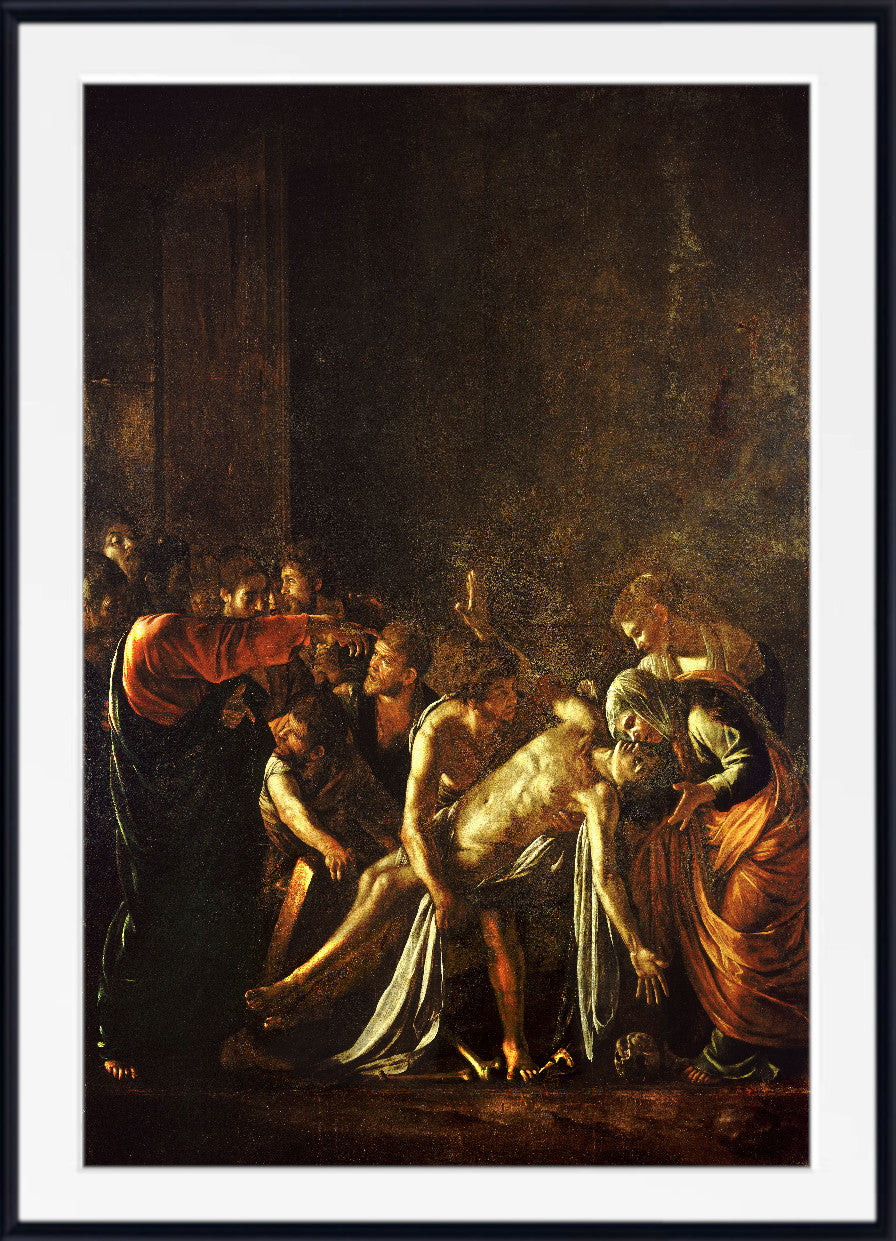

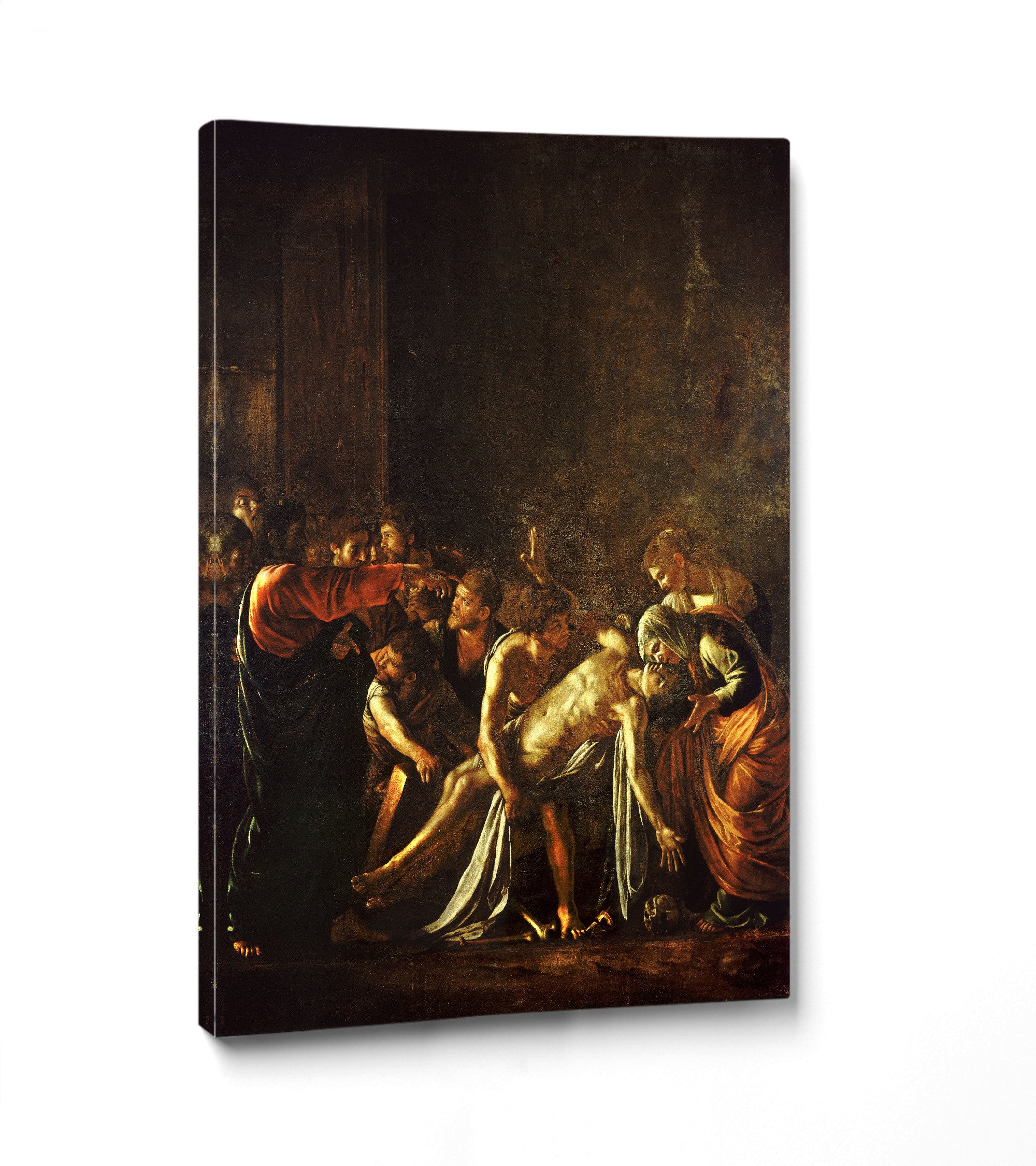

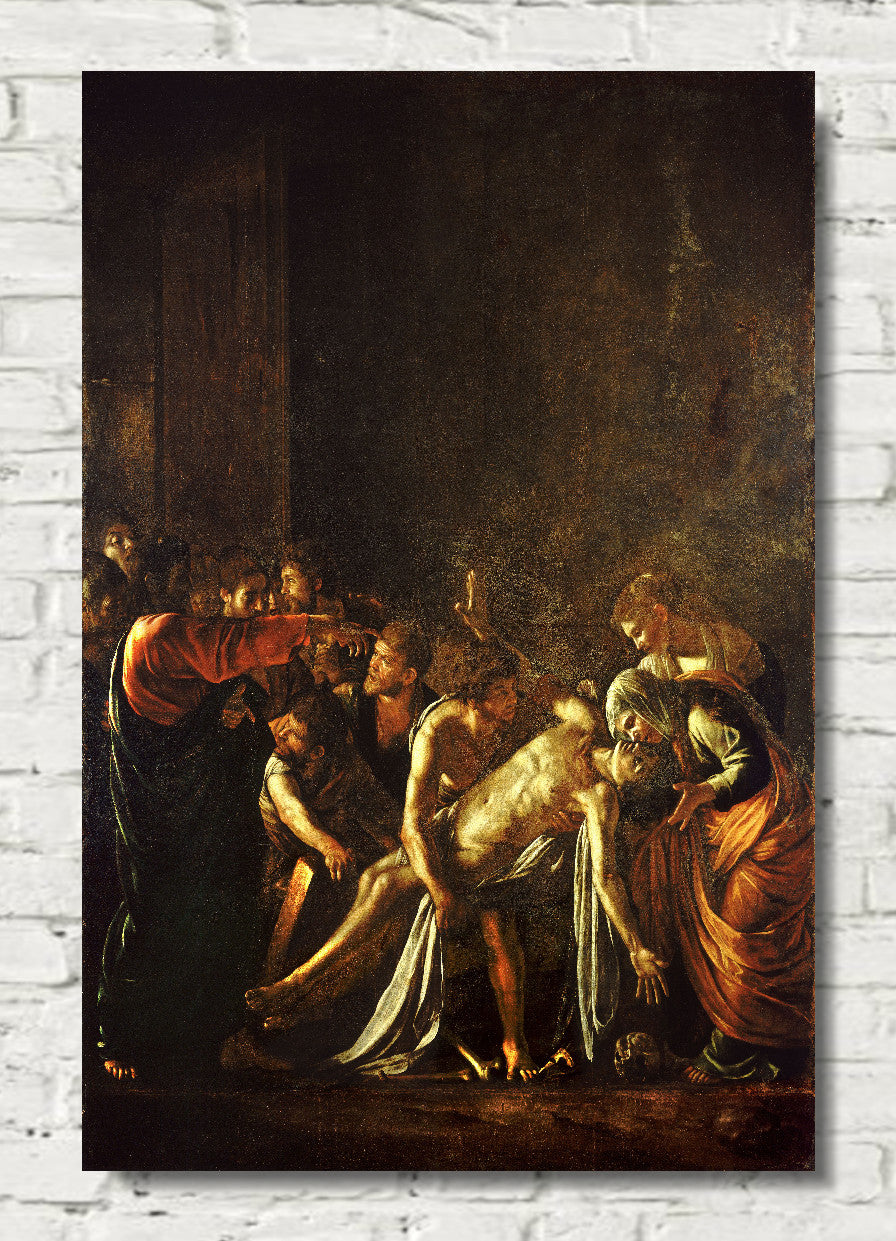

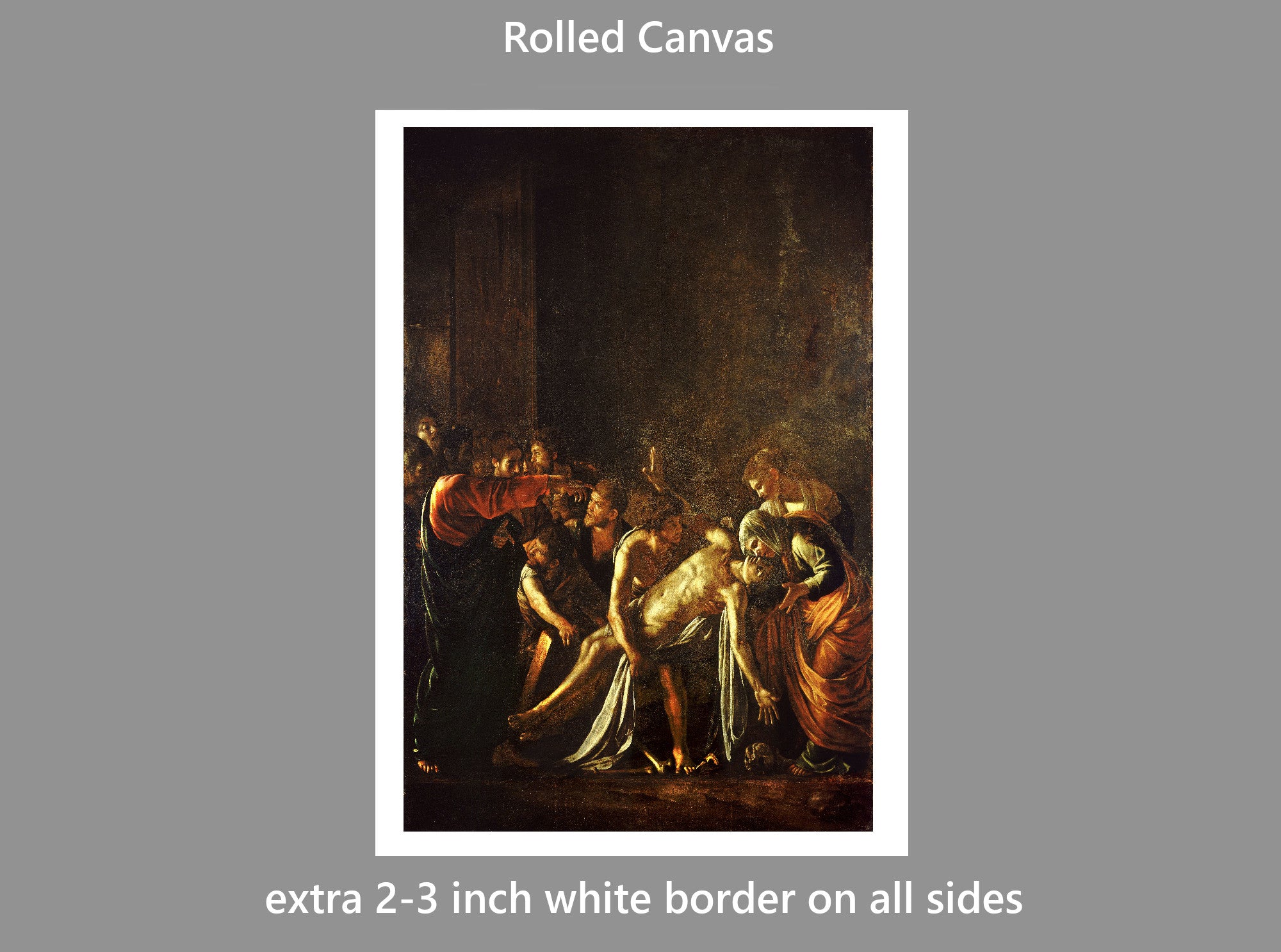

Caravaggio made his way to Sicily where he met his old friend Mario Minniti, who was now married and living in Syracuse. Together they set off on what amounted to a triumphal tour from Syracuse to Messina and, maybe, on to the island capital, Palermo. In Syracuse and Messina Caravaggio continued to win prestigious and well-paid commissions. Among other works from this period are Burial of St. Lucy, The Raising of Lazarus, and Adoration of the Shepherds. His style continued to evolve, showing now friezes of figures isolated against vast empty backgrounds. "His great Sicilian altarpieces isolate their shadowy, pitifully poor figures in vast areas of darkness; they suggest the desperate fears and frailty of man, and at the same time convey, with a new yet desolate tenderness, the beauty of humility and of the meek, who shall inherit the earth." Contemporary reports depict a man whose behaviour was becoming increasingly bizarre, which included sleeping fully armed and in his clothes, ripping up a painting at a slight word of criticism, and mocking local painters. Caravaggio displayed bizarre behaviour from very early in his career. Mancini describes him as "extremely crazy", a letter from Del Monte notes his strangeness, and Minniti's 1724 biographer says that Mario left Caravaggio because of his behaviour. The strangeness seems to have increased after Malta. Susinno's early-18th-century Le vite de' pittori Messinesi ("Lives of the Painters of Messina") provides several colourful anecdotes of Caravaggio's erratic behaviour in Sicily, and these are reproduced in modern full-length biographies such as Langdon and Robb. Bellori writes of Caravaggio's "fear" driving him from city to city across the island and finally, "feeling that it was no longer safe to remain", back to Naples. Baglione says Caravaggio was being "chased by his enemy", but like Bellori does not say who this enemy was.

The Conversion on the Way to Damascus, Caravaggio

Caravaggio - Legacy

Caravaggio's work has been widely influential in late-20th-century American gay culture, with frequent references to male sexual imagery in paintings such as The Musicians and Amor Victorious. British filmmaker Derek Jarman made a critically applauded biopic entitled Caravaggio in 1986. Several poems written by Thom Gunn were responses to specific Caravaggio paintings. In 2013, a touring Caravaggio exhibition called "Burst of Light: Caravaggio and His Legacy" opened in the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut. The show included five paintings by the master artist that included Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness (1604–1605) and Martha and Mary Magdalene (1589). The whole travelled to France and also to Los Angeles, California. Other Baroque artists like Georges de La Tour, Orazio Gentileschi, and the Spanish trio of Diego Velazquez, Francisco de Zurbaran, and Carlo Saraceni were also included in the exhibitions.

Caravaggio - The Complete Works

| Title | Date Painted | Current location |

|---|---|---|

| Boy Peeling Fruit | 1592-3 | Florence, Fondazione Roberto Longhi |

| Boy Peeling Fruit | 1592-3 | London, Picture Gallery, Buckingham Palace – The Royal Collection |

| Boy Peeling Fruit | 1592-3 | Switzerland, Private collection (formerly Ishizuka Collection, Tokyo) |

| Boy Peeling Fruit | 1592-3 | London, The Dickinson Group |

| Portrait of a Prelate | 1592-9 | Italy, Private Collection |

| Young Sick Bacchus | 1593 | Rome, Borghese |

| Boy with a Basket of Fruit | 1593 | Rome, Borghese |

| Fortune Teller | 1594 | Rome, Capitoline Museums |

| Cardsharps | 1594 | Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum |

| Musicians | 1595 | New York City, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

| Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy | 1595 | Hartford, Connecticut, Wadsworth Atheneum |

| Boy Bitten by a Lizard | 1596 | London, National Gallery |

| Lute Player | 1596 | St. Petersburg, Hermitage Museum |

| Lute Player | 1596 | New York City, Metropolitan Museum of Art (on loan) |

| Basket of Fruit | 1596 | Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana |

| Bacchus | 1596 | Florence, Uffizi |

| Penitent Magdalene | 1597 | Rome, Doria Pamphilj Gallery |

| Rest on the Flight into Egypt | 1597 | Rome, Doria Pamphilj Gallery |

| Medusa | 1597 | Florence, Uffizi |

| Portrait of a Courtesan | 1597 | Berlin, Kaiser Friedrich Museum |

| Jupiter, Neptune and Pluto | 1597 | Rome, Casino di Villa Boncompagni Ludovisi |

| Fortune Teller | 1597 | Paris, Musée du Louvre |

| Saint Catherine of Alexandria | 1598 | Madrid, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum |

| Sacrifice of Isaac | 1598 | Princeton, Barbara Piasecka-Johnson Collection |

| John the Baptist | 1598 | Toledo, Cathedral Museum |

| Martha and Mary Magdalene | 1598 | Detroit, Detroit Institute of Arts |

| Portrait of Maffeo Barberini | 1598 | Florence, Private Collection |

| Judith Beheading Holofernes | 1598 | Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini |

| David and Goliath | 1599 | Madrid, Prado |

| Narcissus | 1599 | Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini |

| Boy Bitten by a Lizard | 1600 | Florence, Fondazione Roberto Longhi |

| John the Baptist | 1600 | Basel, Öffentliche Kunstsammlung |

| Calling of Saint Matthew | 1600 | Rome, Contarelli Chapel |

| Martyrdom of Saint Matthew | 1600 | Rome, Contarelli Chapel |

| Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence | 1600-9 | Palermo, Church of San Lorenzo |

| Conversion of Saint Paul | 1600 | Rome, Odescalchi Balbi Collection |

| Crucifixion of Saint Peter | 1601 | Rome, Cerasi Chapel |

| Conversion of Saint Paul on the Road to Damascus | 1601 | Rome, Cerasi Chapel |

| Still Life with Flowers and Fruit | 1601 | Rome, Borghese |

| The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (Ecclesiastical Version) | 1601 | Florence, Private Collection |

| Supper at Emmaus | 1602 | London, National Gallery |

| Amor Victorious | 1602 | Berlin, Gemäldegalerie |

| Saint Matthew and the Angel | 1602 | Berlin, Kaiser Friedrich Museum |

| Inspiration of Saint Matthew | 1602 | Rome, Contarelli Chapel |

| John the Baptist | 1602 | Rome, Capitoline Museums |

| John the Baptist | 1602 | Rome, Doria Pamphilj Gallery |

| Incredulity of Saint Thomas (Secular version) | 1602 | Potsdam, Sanssouci |

| Taking of Christ | 1602 | Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland |

| Sacrifice of Isaac | 1603 | Florence, Uffizi |

| Holy Family with St. John the Baptist | 1603 | New York City, Metropolitan Museum of Art (on loan) |

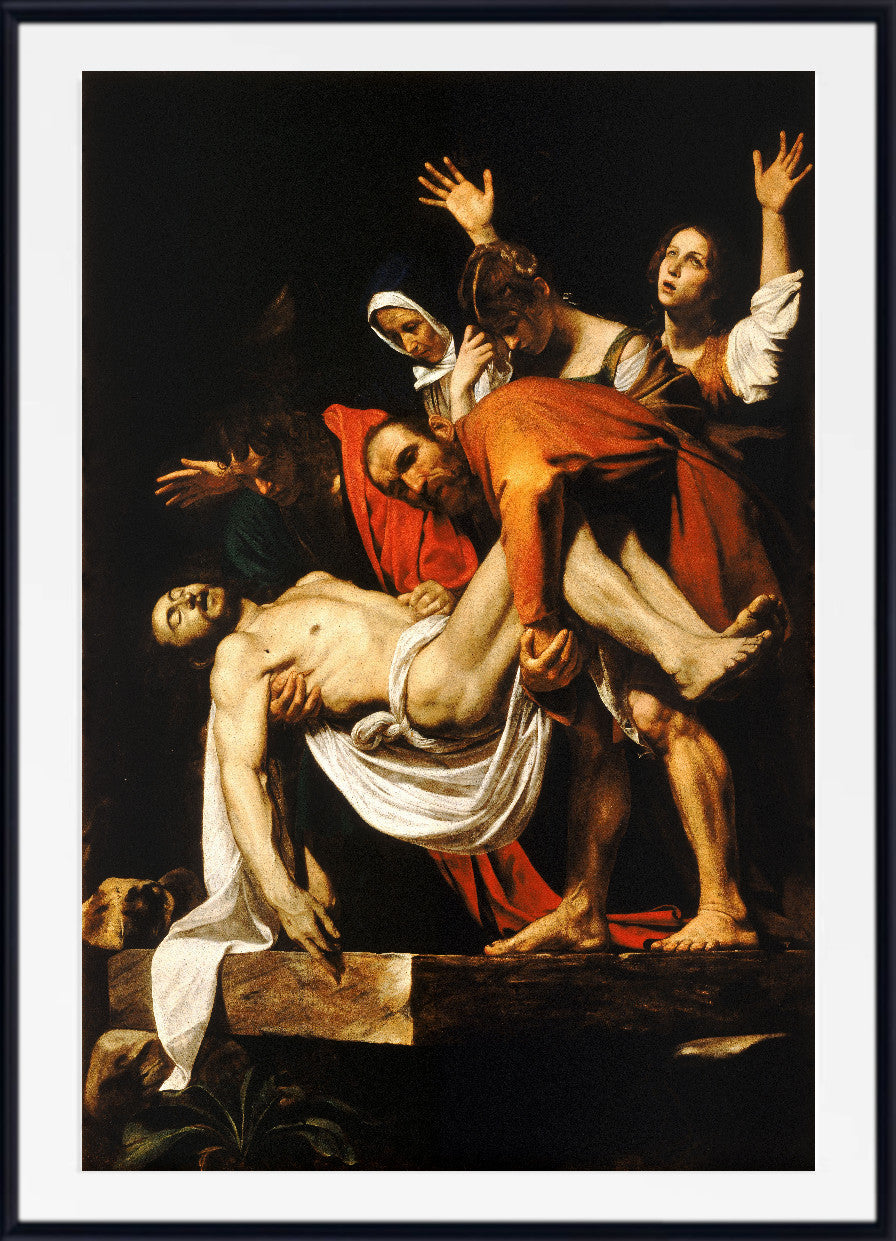

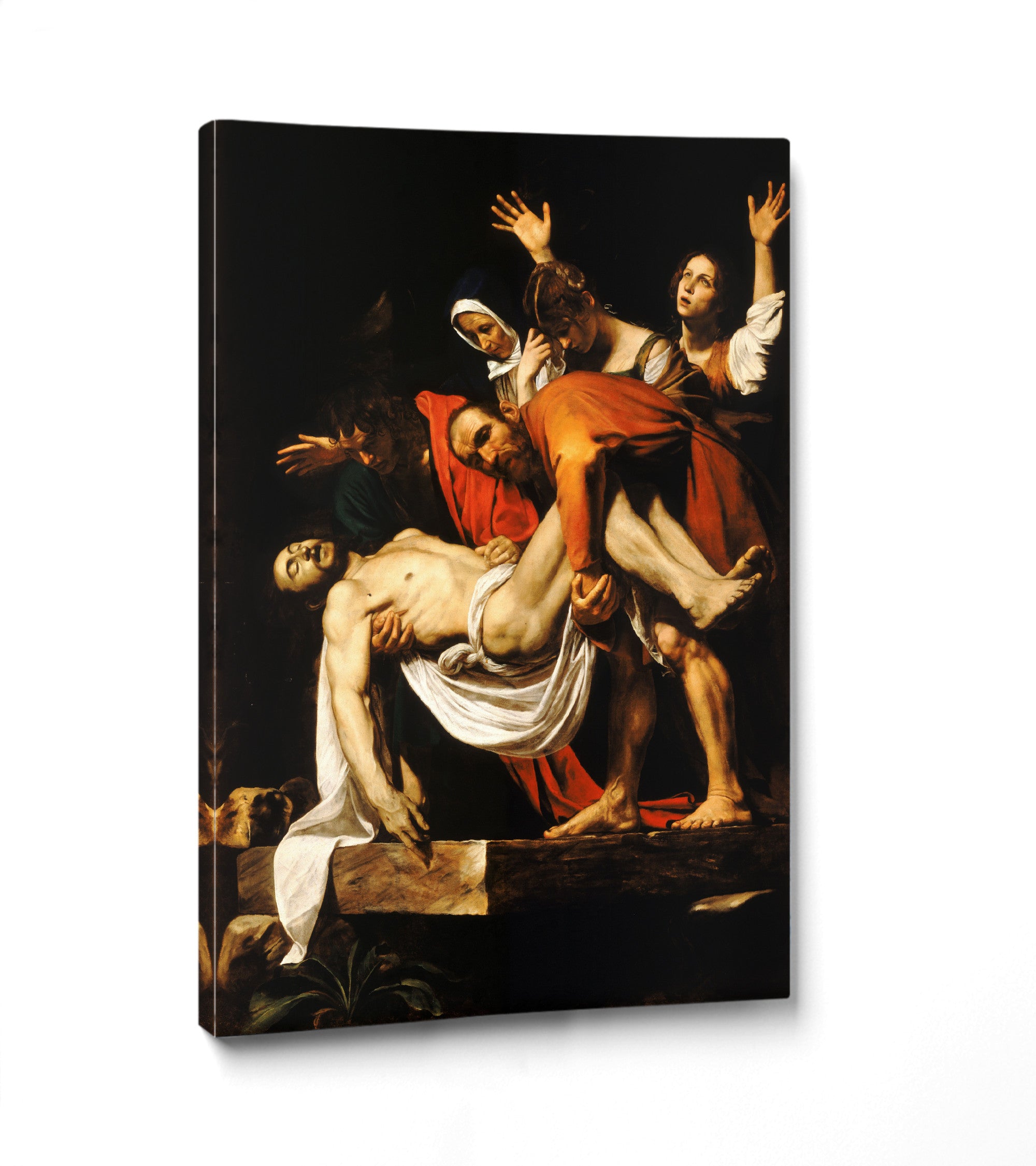

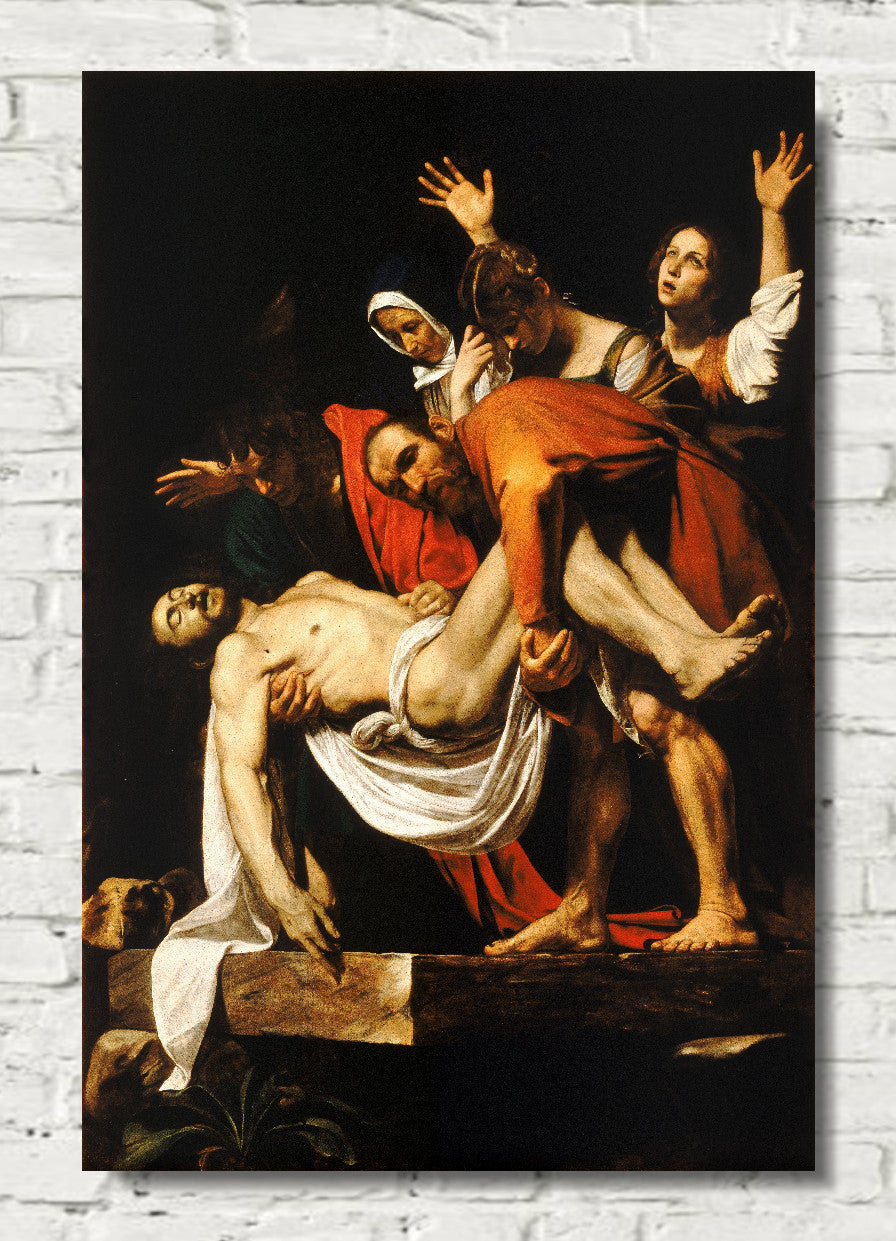

| Entombment | 1603 | Vatican City, Vatican Museums |

| Crowning with Thorns | 1603 | Prato, Cariprato Bank |

| Madonna of Loreto | 1604 | Rome, Sant'Agostino |

| John the Baptist | 1604 | Kansas City, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art |

| John the Baptist | 1604 | Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Corsini |

| The Calling of Saints Peter and Andrew | 1604 | London, Hampton Court Palace – The Royal Collection |

| Christ on the Mount of Olives | 1605 | Berlin, Kaiser Friedrich Museum |

| Ecce Homo | 1605 | Genoa, Palazzo Bianco |

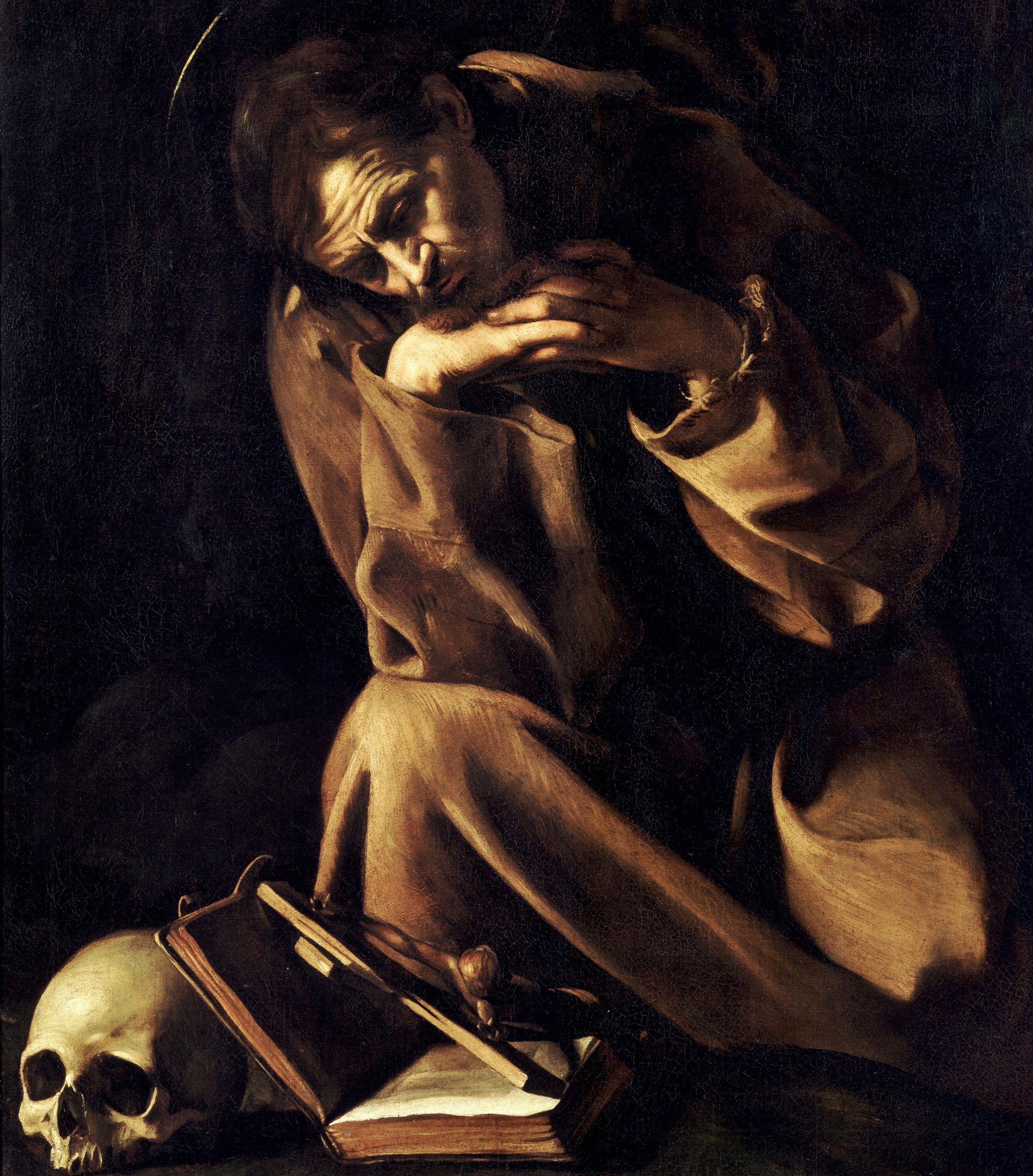

| Saint Jerome in Meditation | 1605 | Montserrat, Museum of Montserrat |

| Saint Jerome Writing | 1605 | Rome, Borghese |

| Portrait of Pope Paul V | 1605 | Rome, Private Collection of the Prince Borghese |

| Still Life with Fruit on a Stone Ledge | 1605 | Rome, Borghese |

| Madonna and Child with St. Anne (Dei Palafrenieri) | 1606 | Rome, Borghese |

| Death of the Virgin | 1606 | Paris, Musée du Louvre |

| Magdalene grieving | 1606 | Rome, Private Collection |

| Mary Magdalen in Ecstasy | 1606 | Rome, Private collection |

| Saint Francis in Meditation | 1606 | Cremona, Museo Civico Ala Ponzone |

| Supper at Emmaus | 1606 | Milan, Brera Fine Arts Academy |

| Judith Beheading Holofernes | 1607 | New York, J. Tomilson Hill collection |

| Seven Works of Mercy | 1607 | Naples, Pio Monte della Misericordia |

| Crucifixion of Saint Andrew | 1607 | Cleveland, Cleveland Museum of Art |

| David with the Head of Goliath | 1607 | Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

| Madonna of the Rosary (Madonna del Rosario) | 1607 | Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

| Crowning with Thorns | 1607 | Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

| Flagellation of Christ | 1607 | Naples, Museo di Capodimonte |

| Christ at the Column | 1607 | Rouen, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

| Salome with the Head of John the Baptist | 1607 | London, National Gallery |

| Saint Jerome Writing | 1607 | Valletta, St. John's Co-Cathedral |

| Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt and his Page | 1608 | Paris, Musée du Louvre |

| Portrait of Fra Antonio Martelli | 1608 | Florence, Pitti Palace |

| Beheading of Saint John the Baptist | 1608 | Valletta, St. John's Co-Cathedral |

| Sleeping Cupid | 1608 | Florence, Pitti Palace |

| John the Baptist | 1608 | Valletta, MUZA, The Malta National Community Art Museum |

| Annunciation | 1608 | Nancy, Musée des Beaux-Arts |

| Burial of Saint Lucy | 1608 | Syracuse, Santuario di Santa Lucia al Sepolcro |

| Raising of Lazarus | 1609 | Messina, Museo Regionale |

| Adoration of the Shepherds | 1609 | Messina, Museo Regionale |

| Salome with the Head of John the Baptist | 1609 | Madrid, Royal Palace of Madrid |

| Tooth Puller | 1609 | Florence, Pitti Palace |

| Denial of Saint Peter | 1610 | New York City, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

| Saint Francis in Prayer | 1610 | Rome, Church of San Pietro in Carpineto Romano |

| John the Baptist | 1610 | Rome, Borghese |

| David with the Head of Goliath | 1610 | Rome, Borghese |

| John the Baptist | 1610 | Munich, Private collection |

| Martyrdom of Saint Ursula | 1610 | Naples, Galleria di Palazzo Zevallos Stigliano |