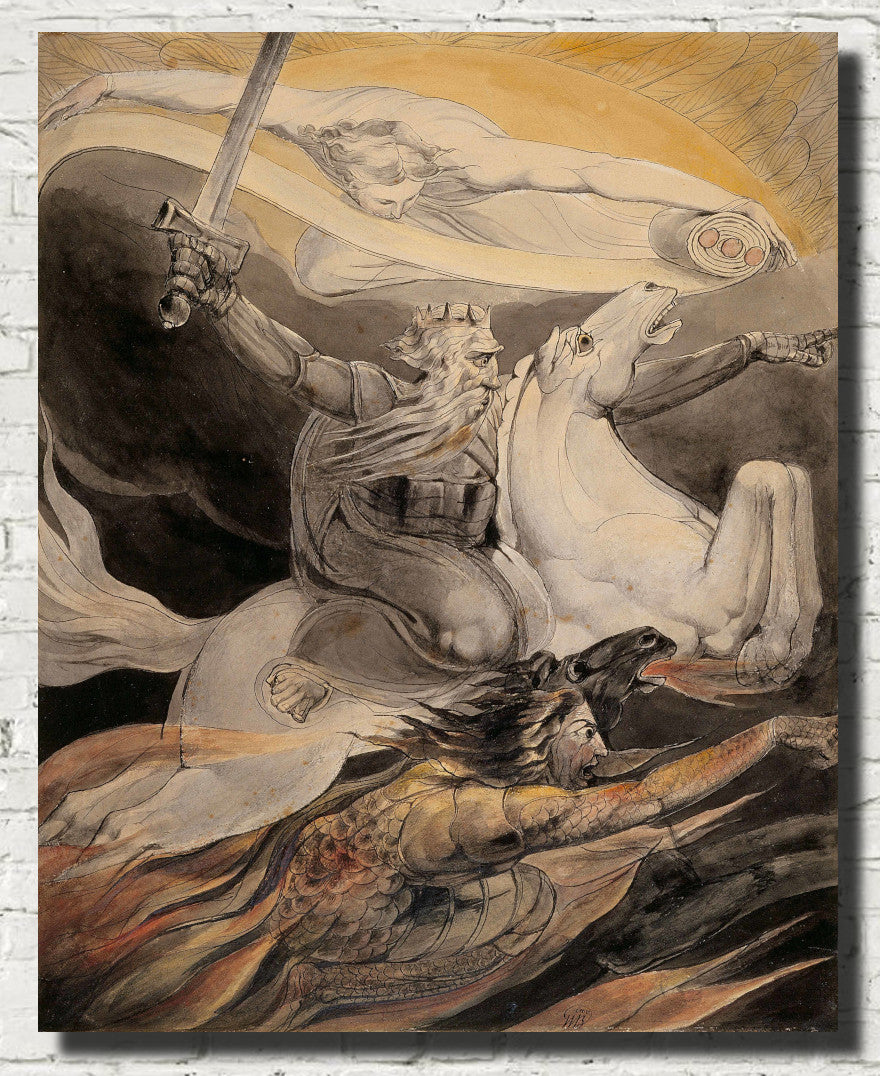

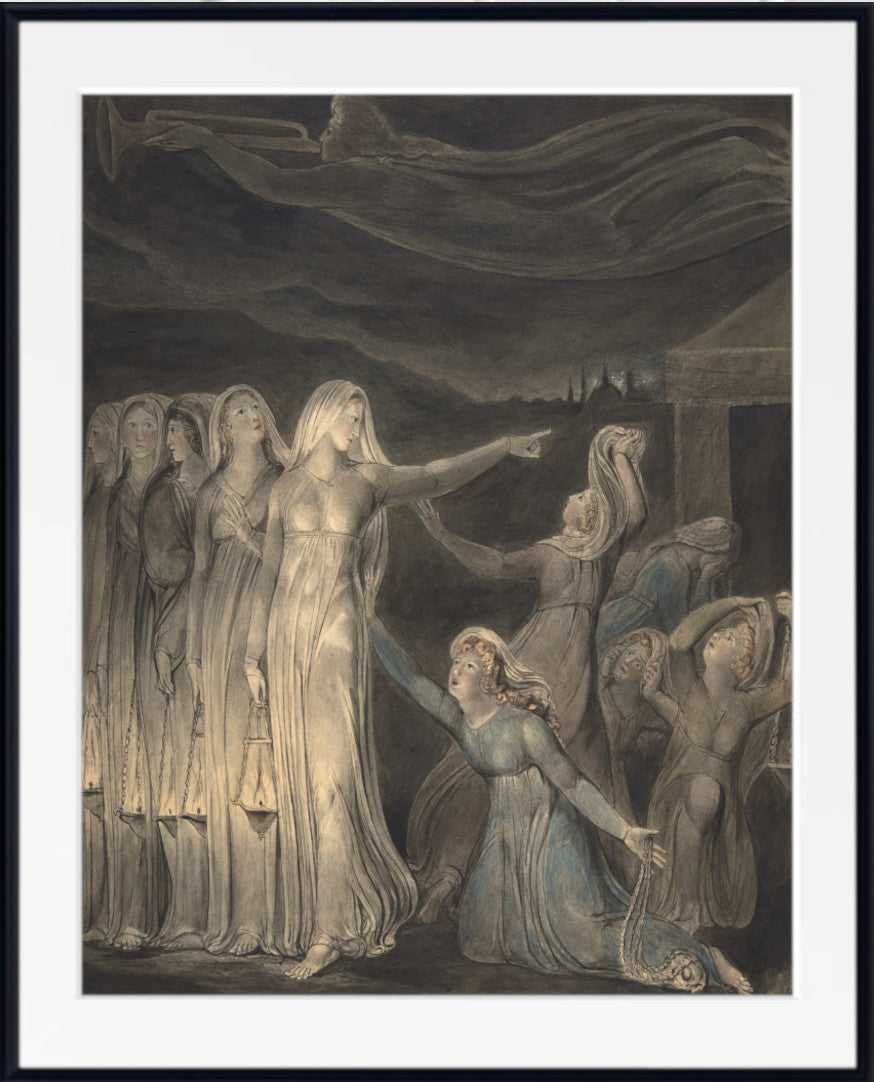

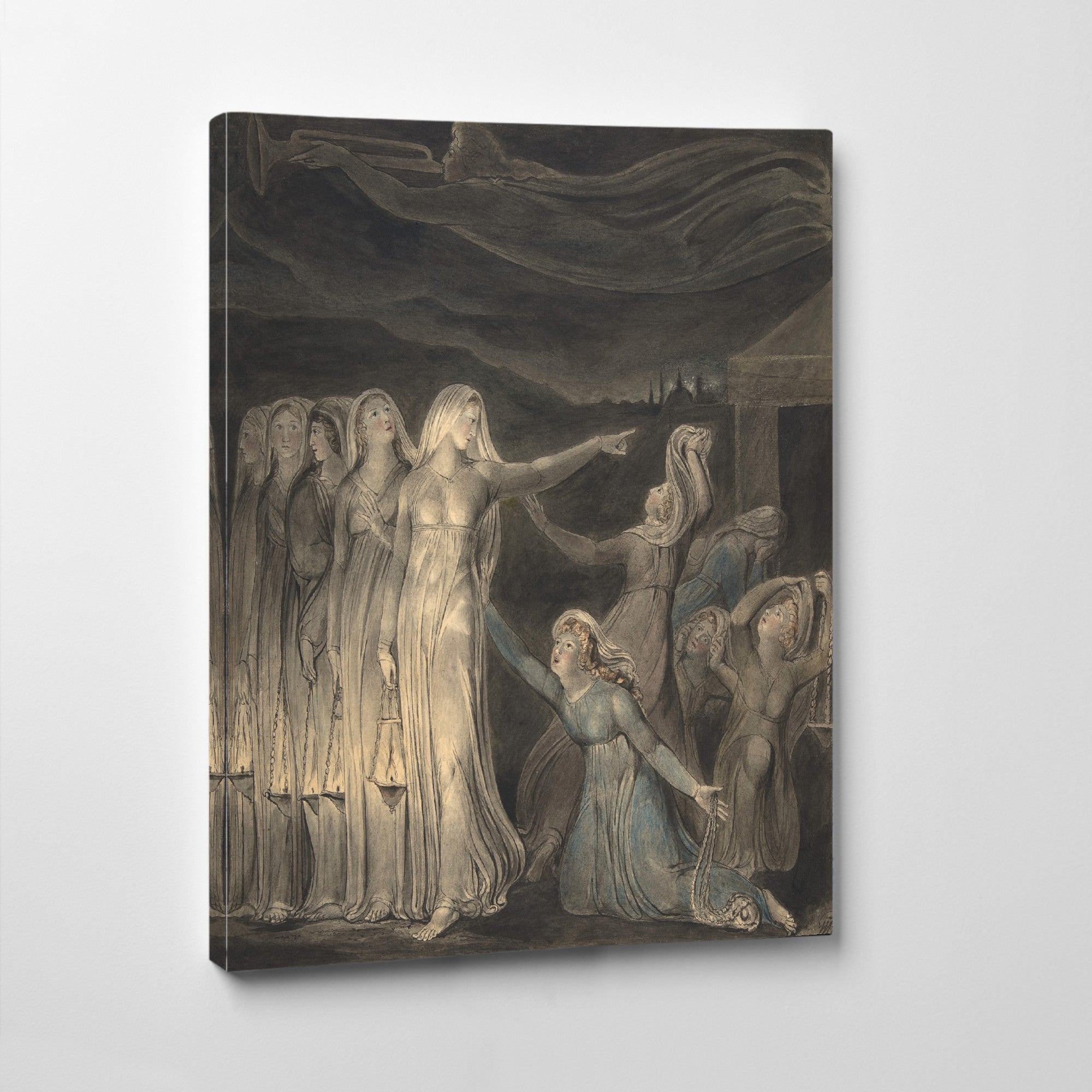

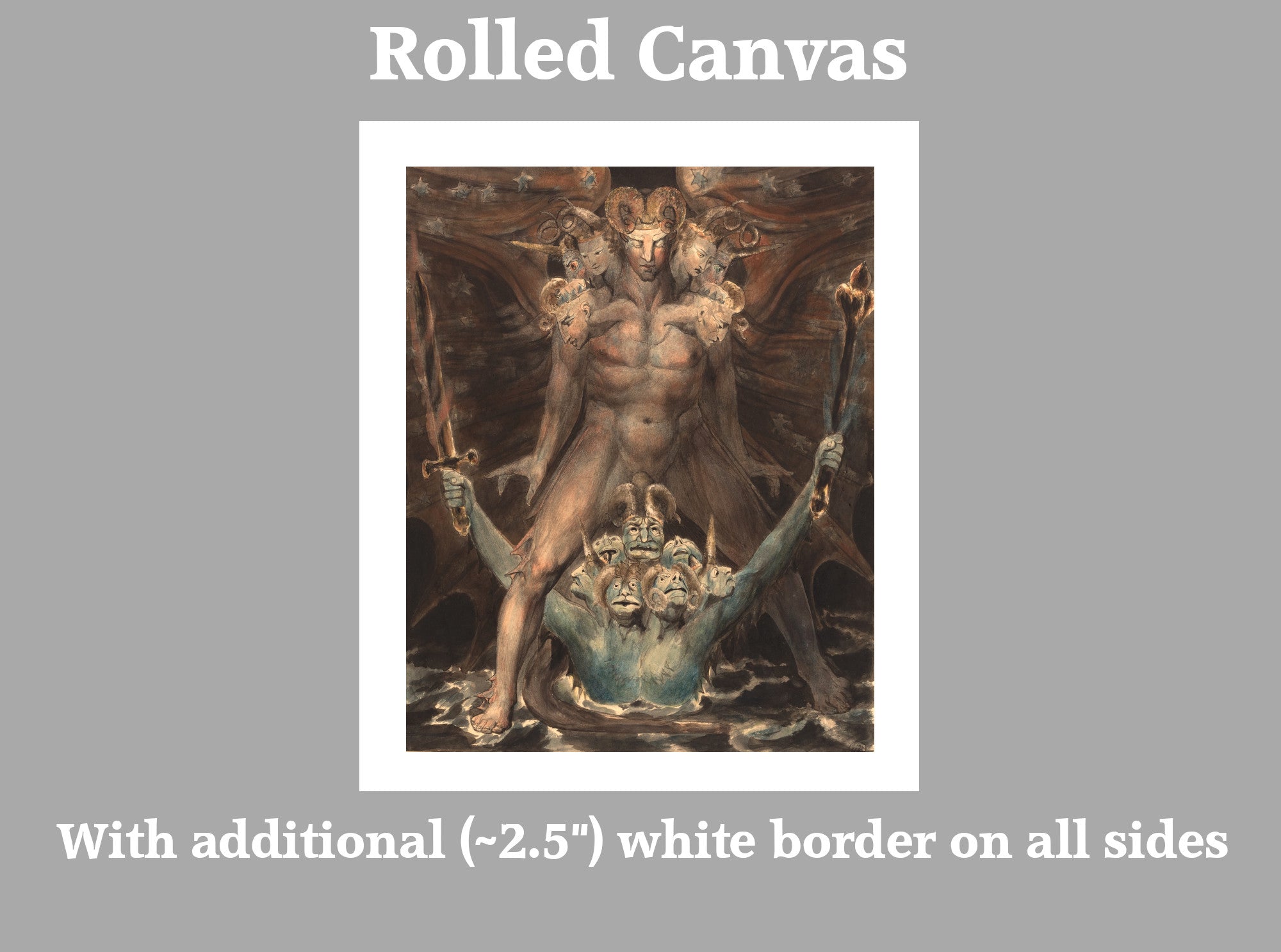

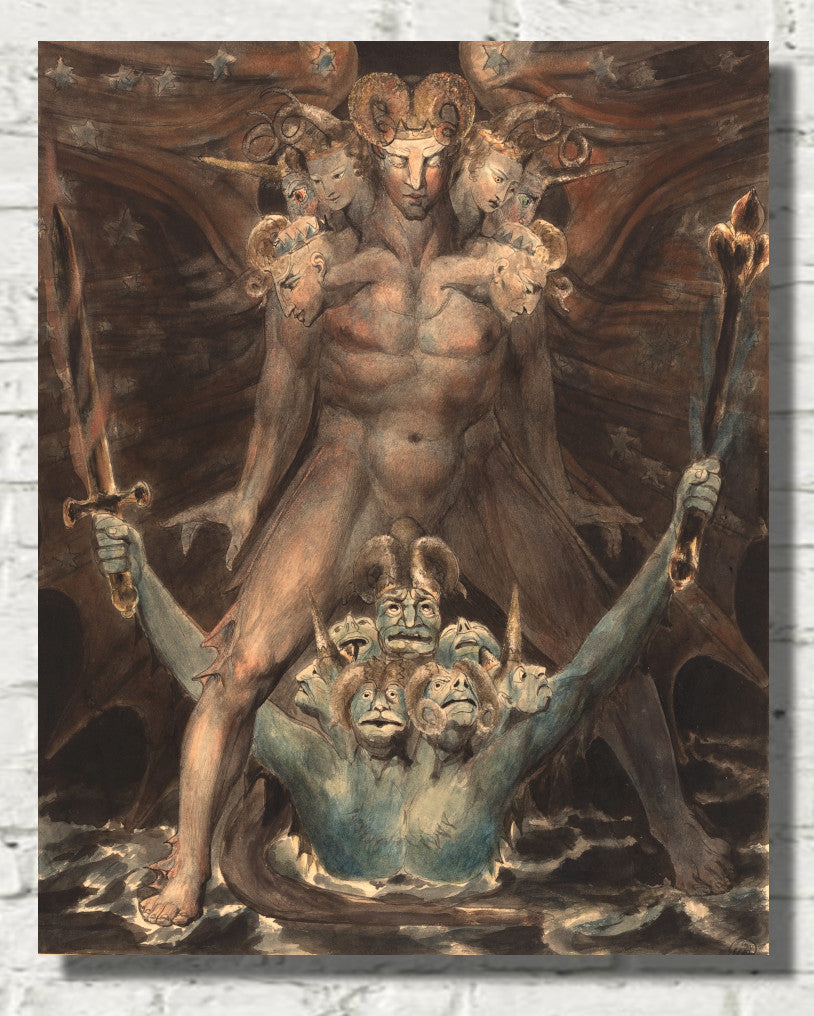

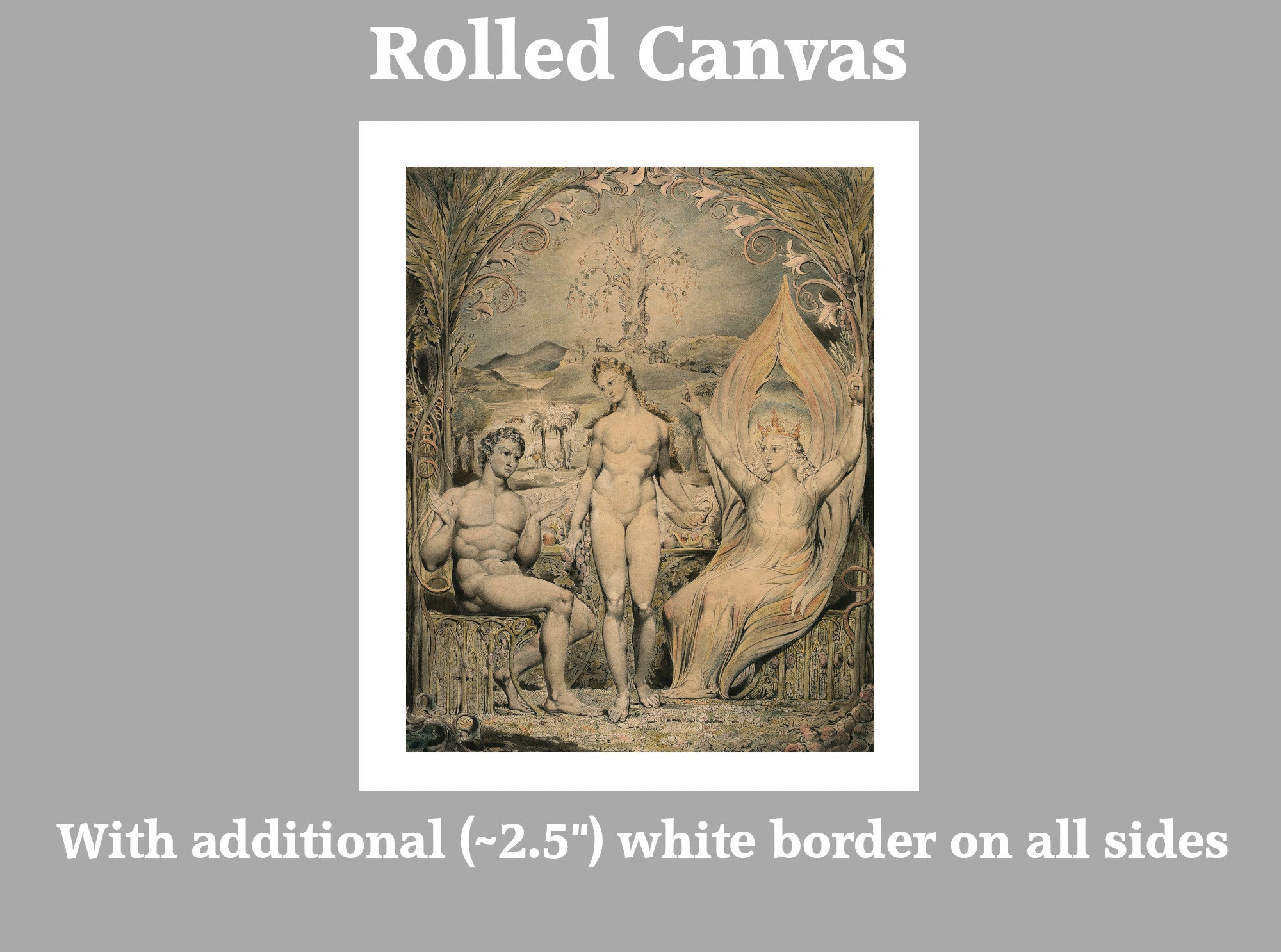

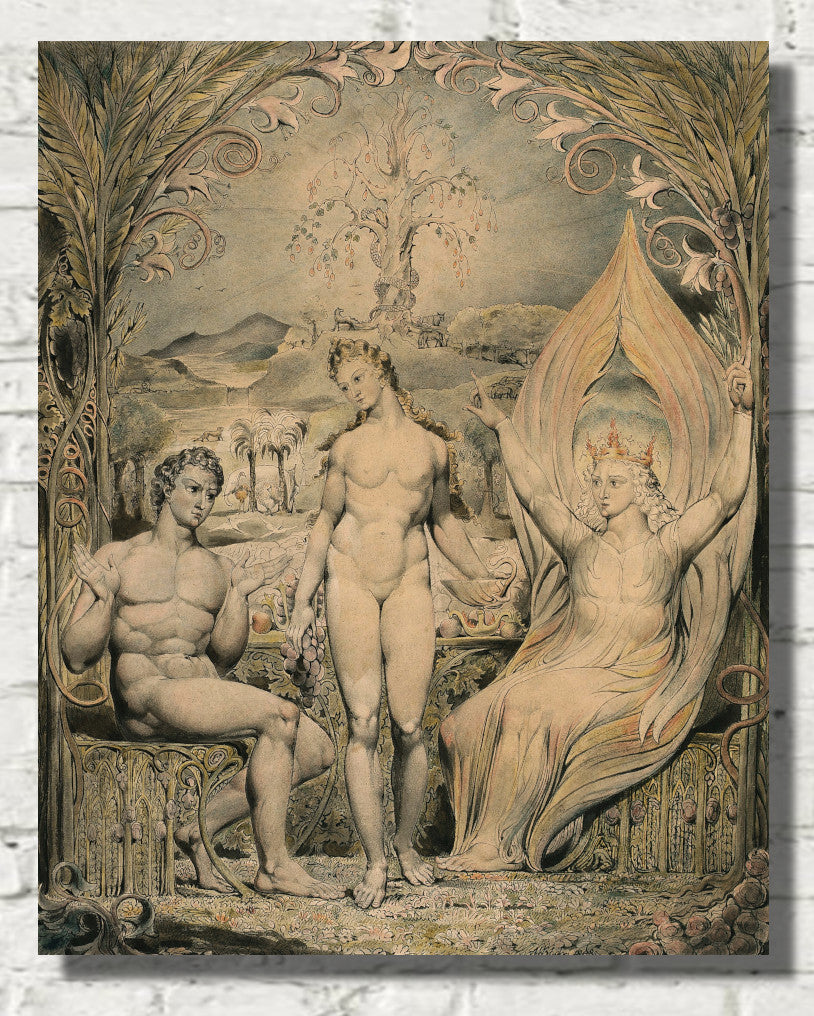

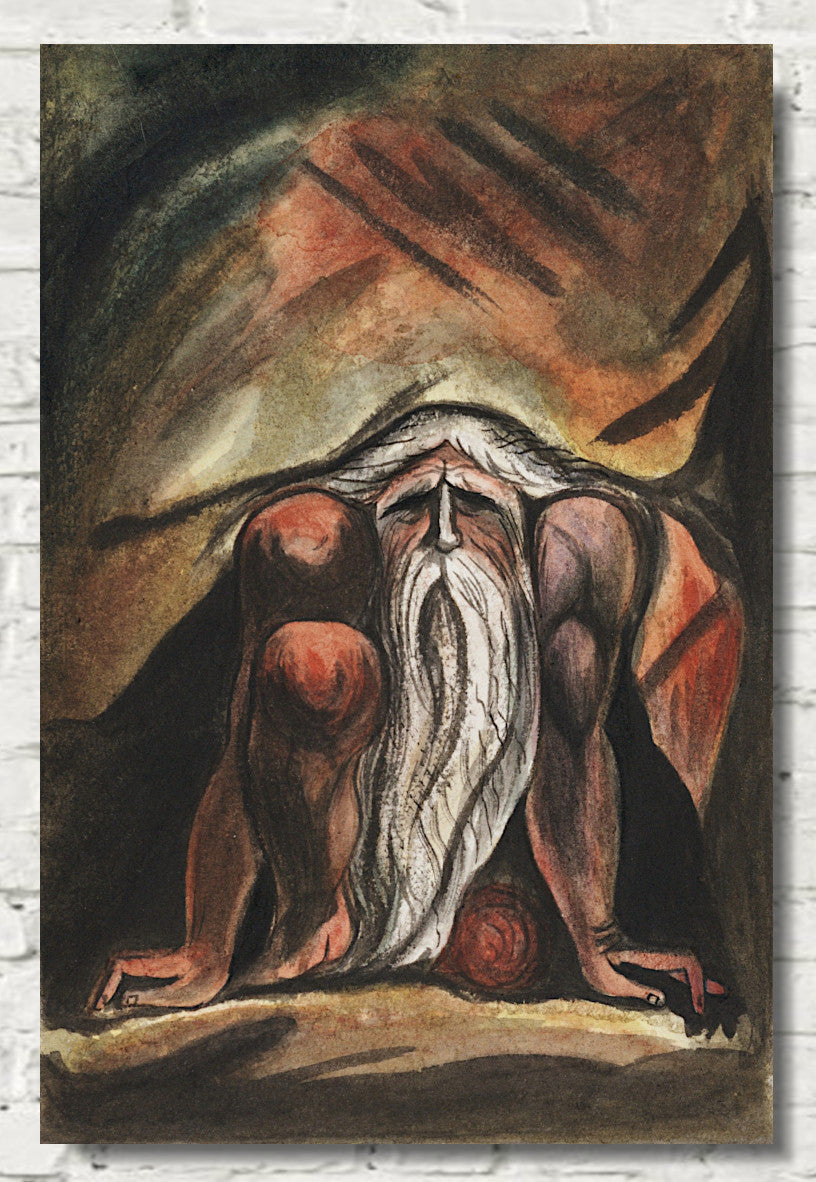

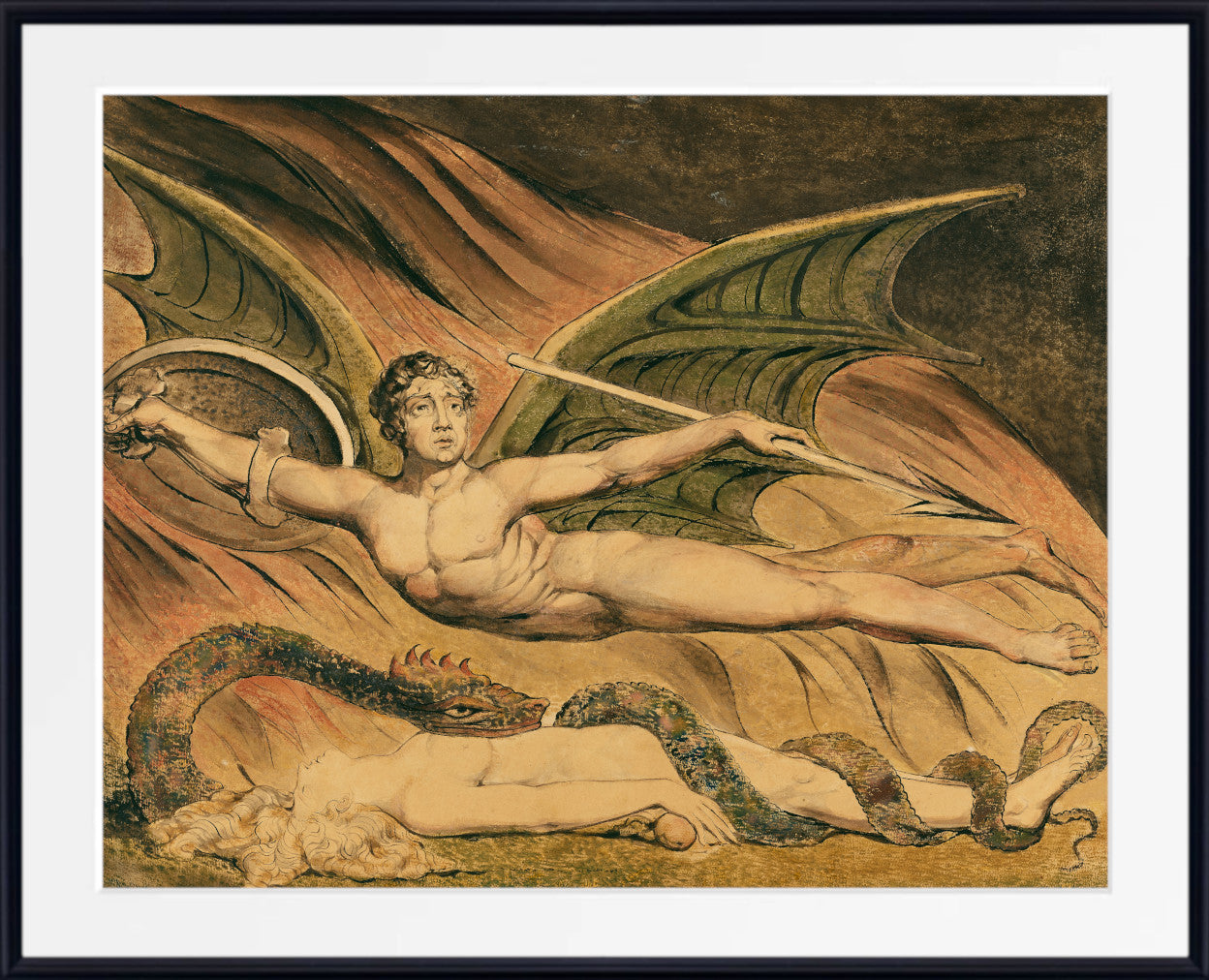

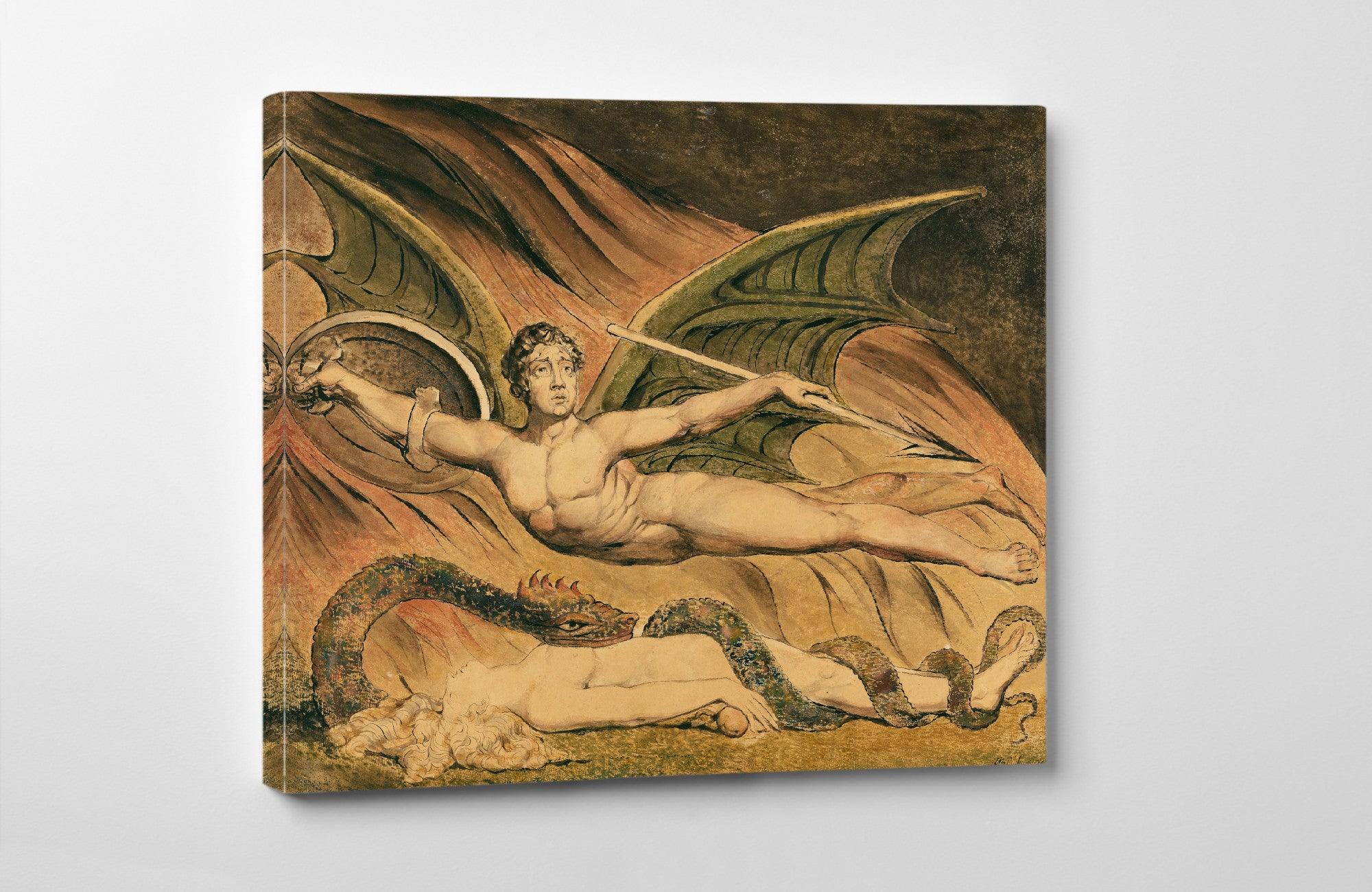

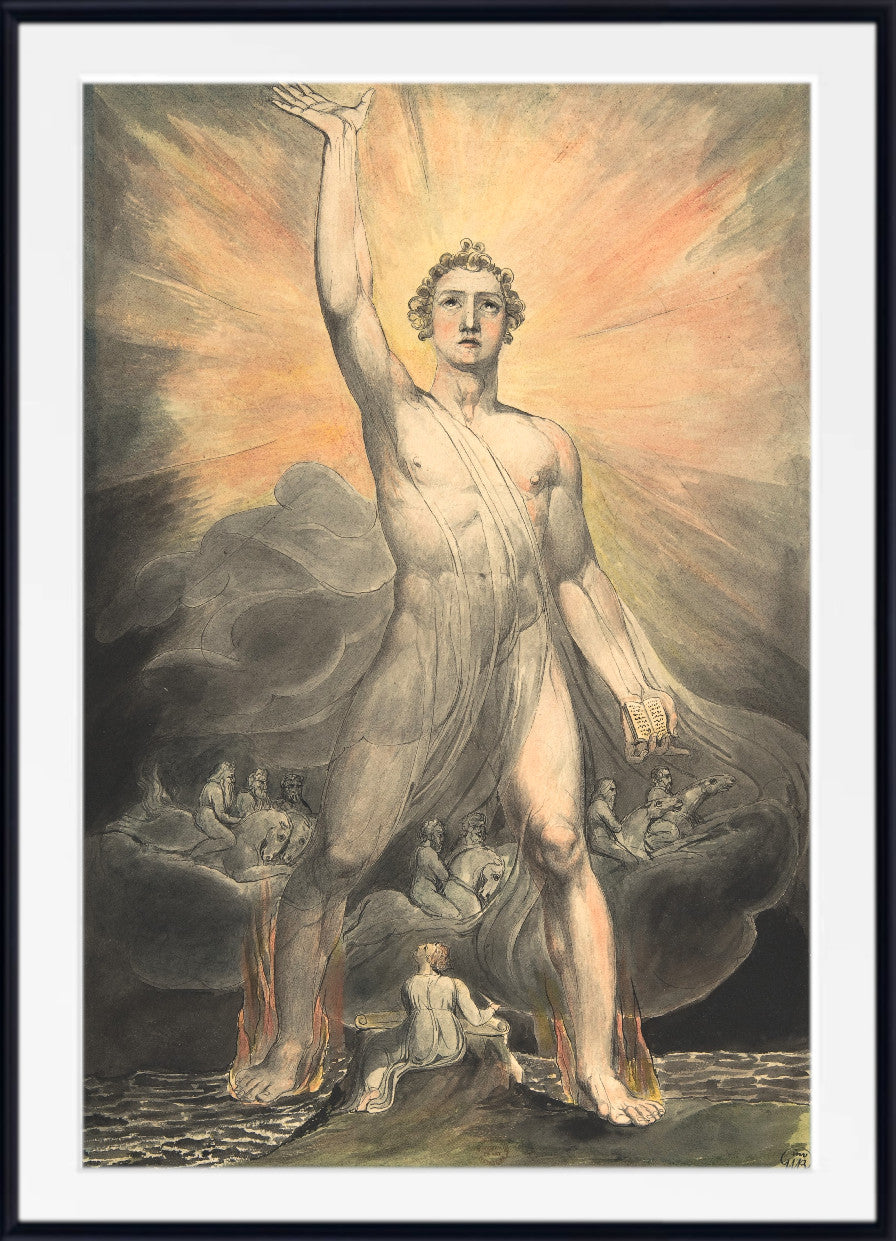

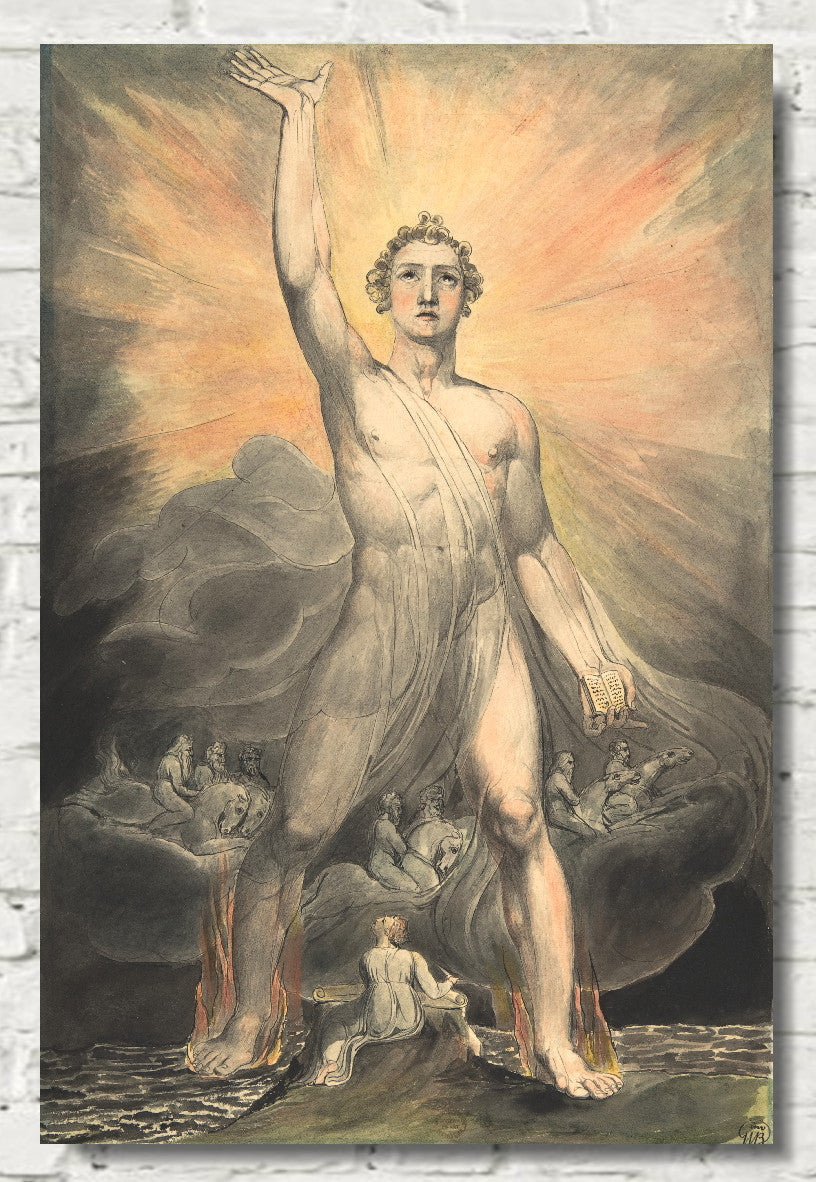

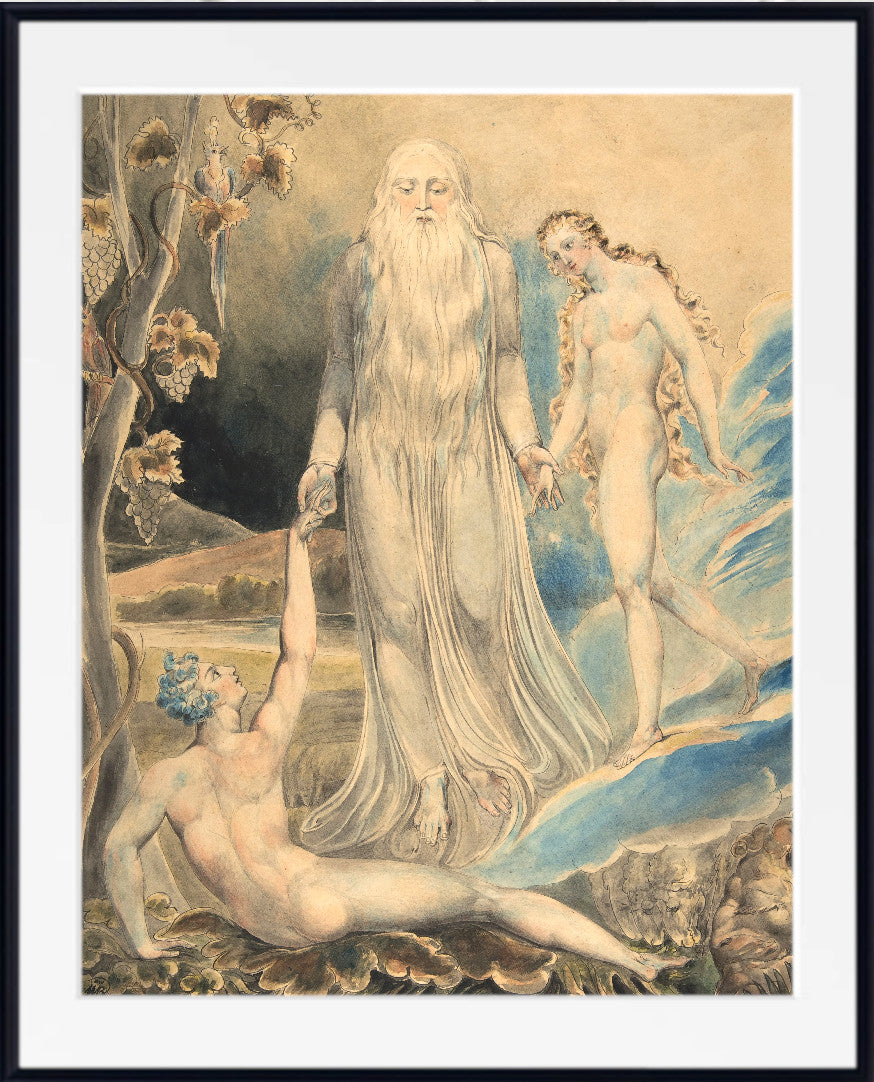

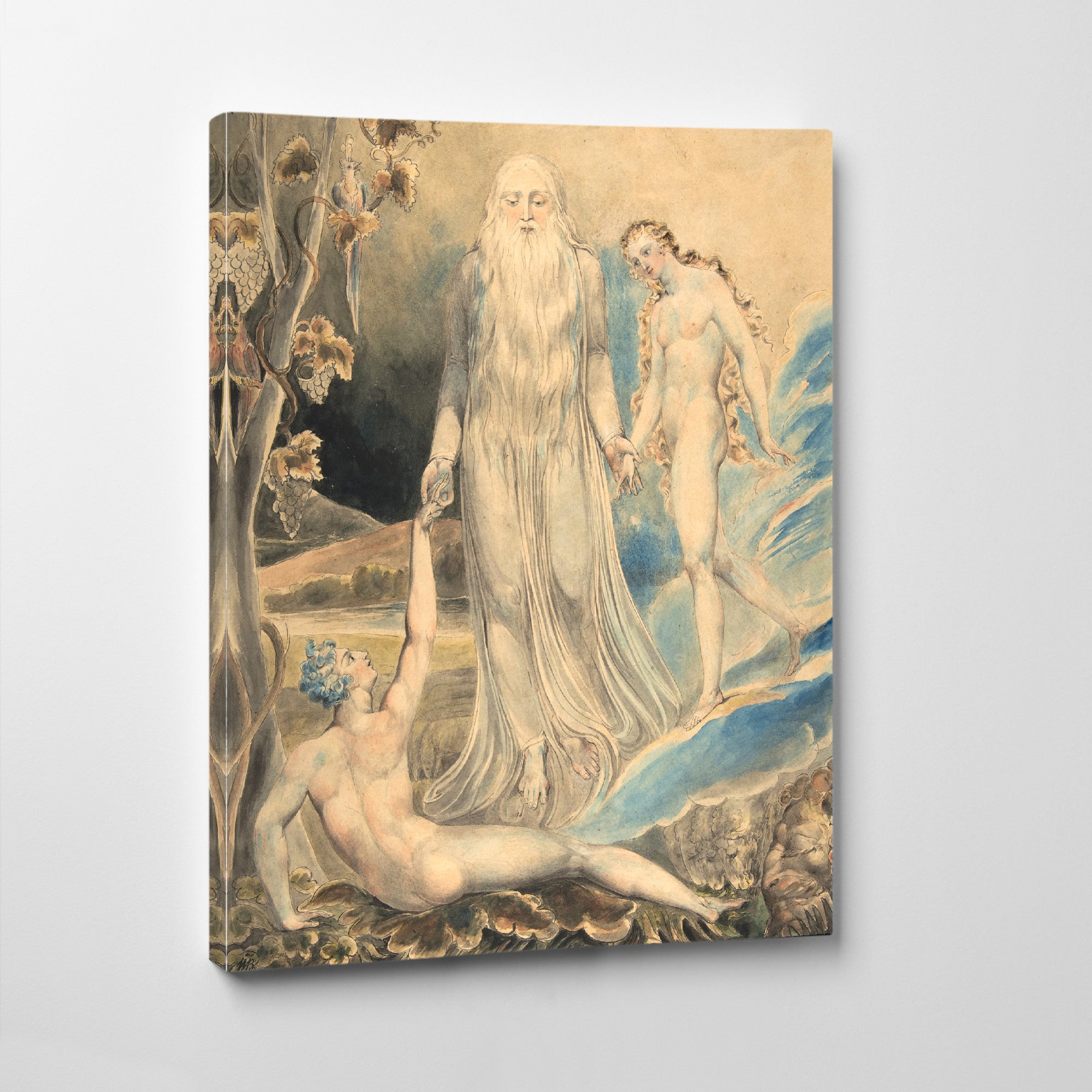

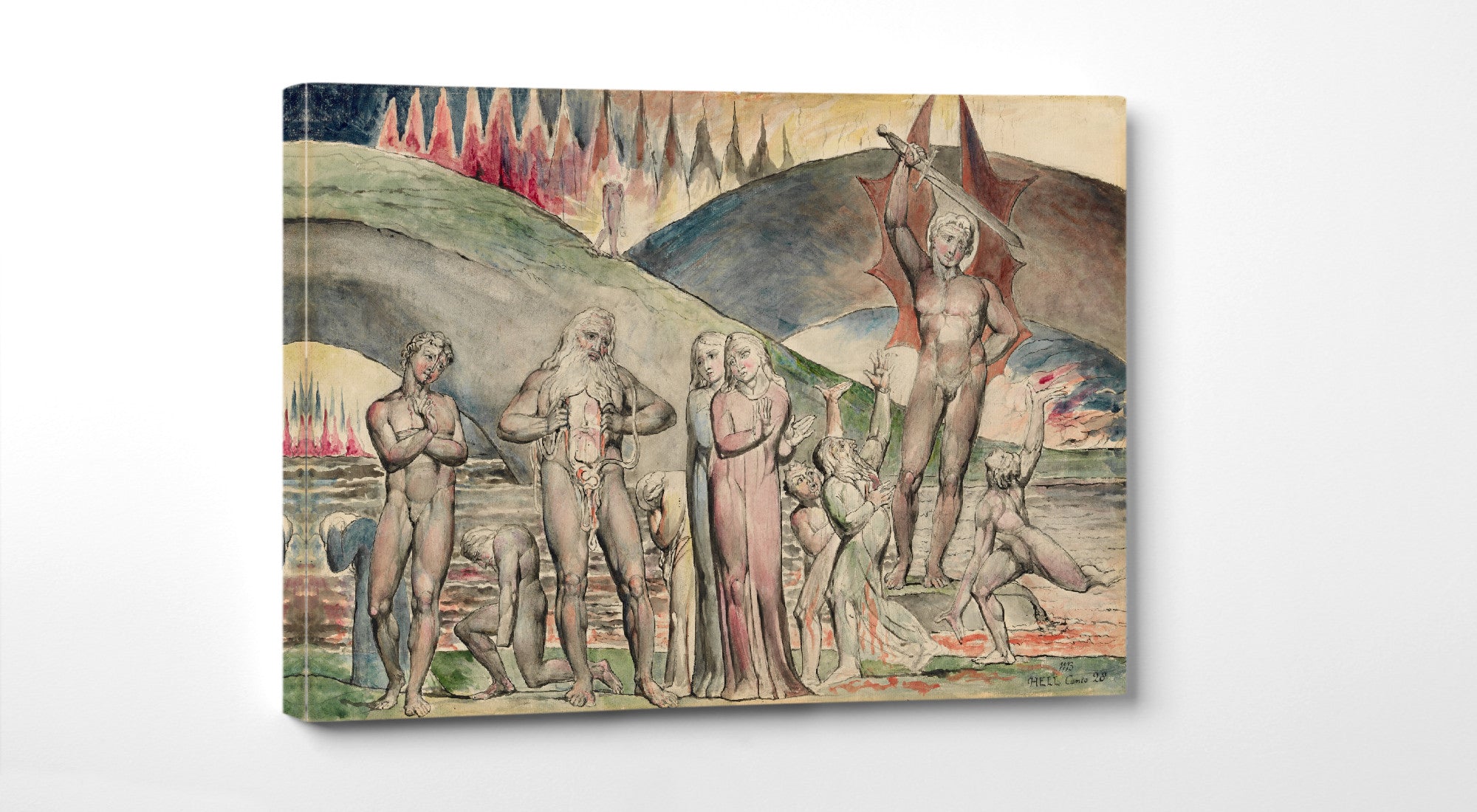

Satan Exulting over Eve, William Blake

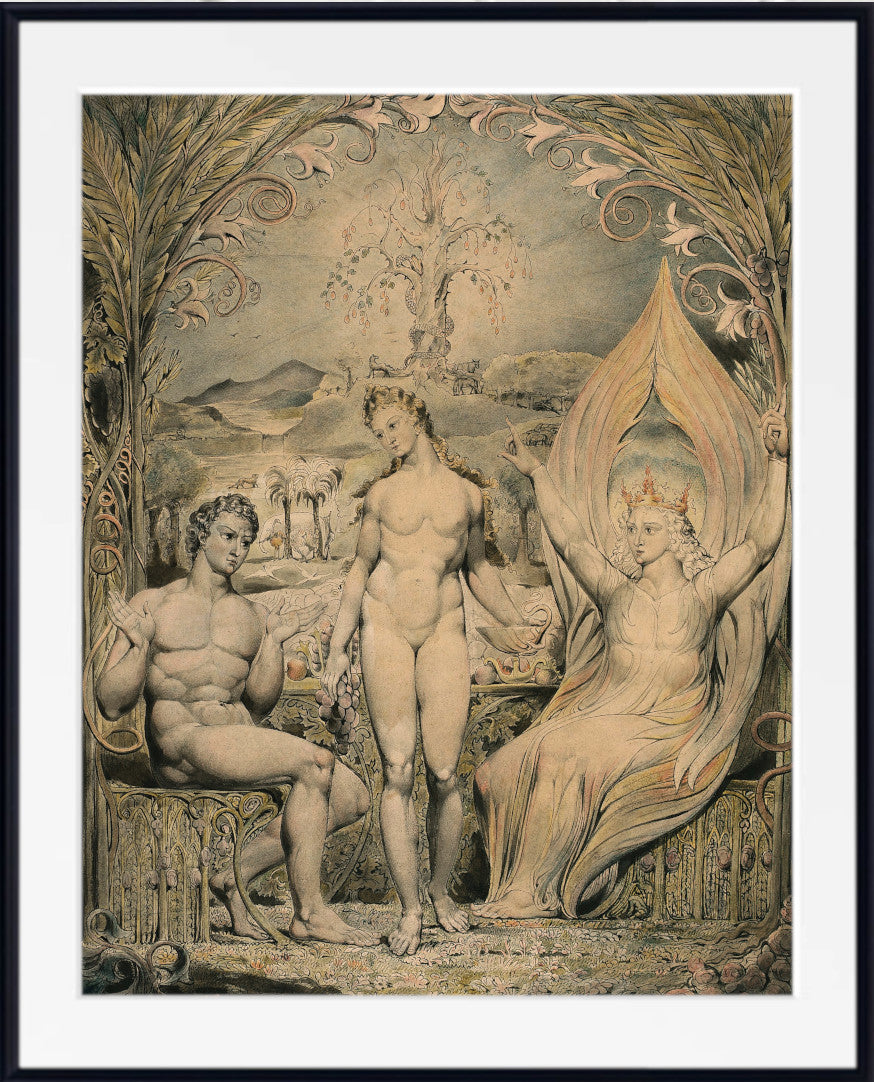

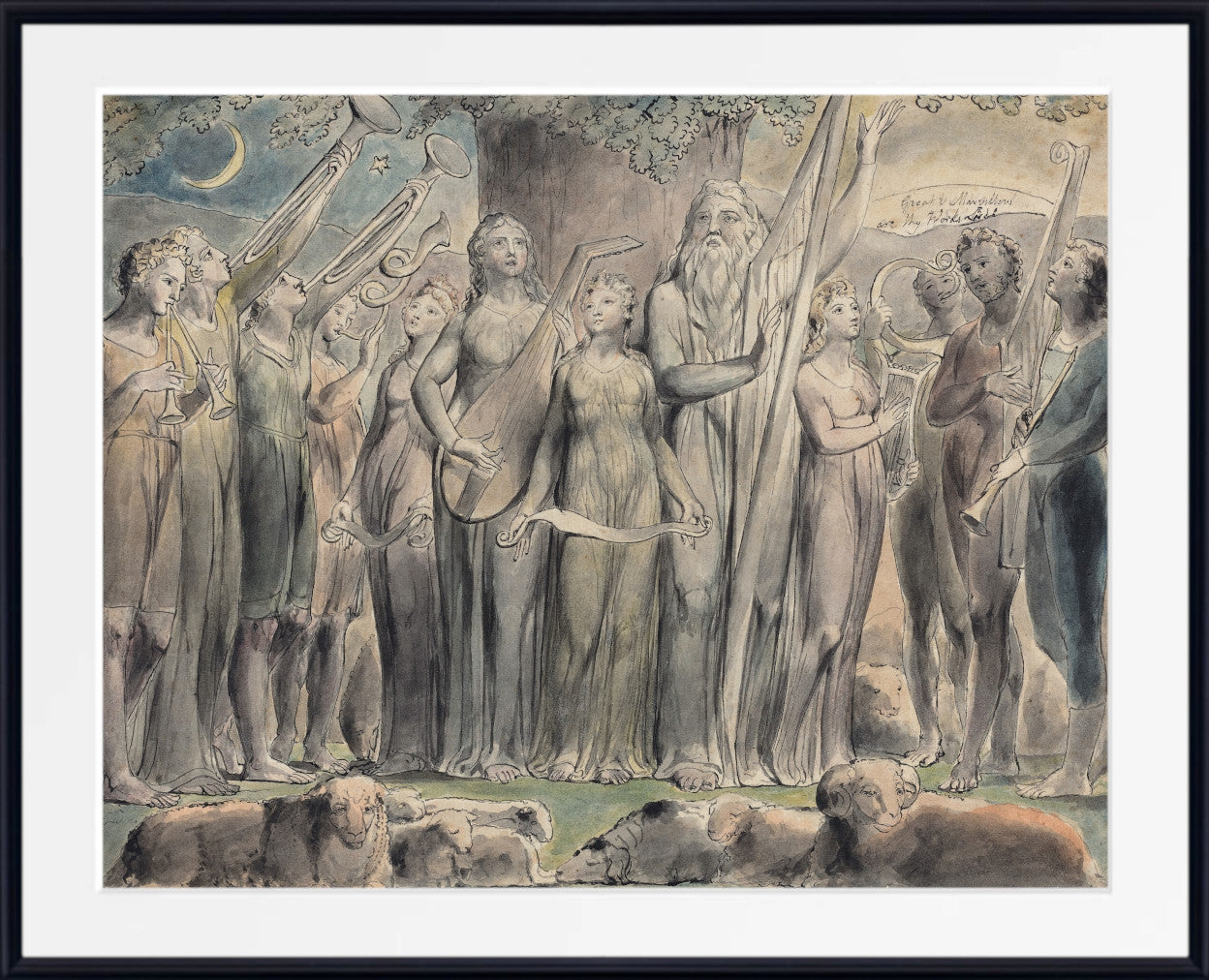

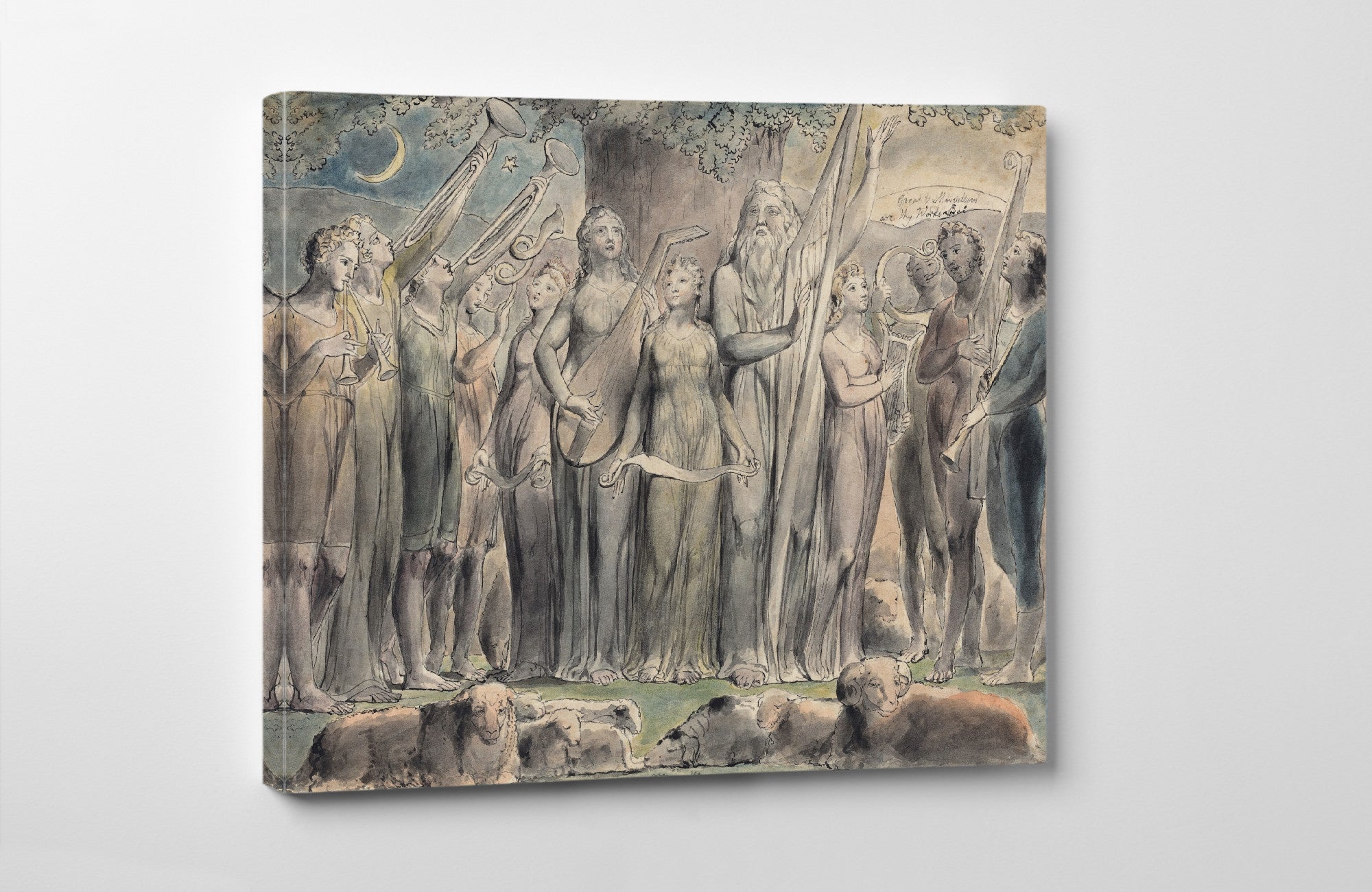

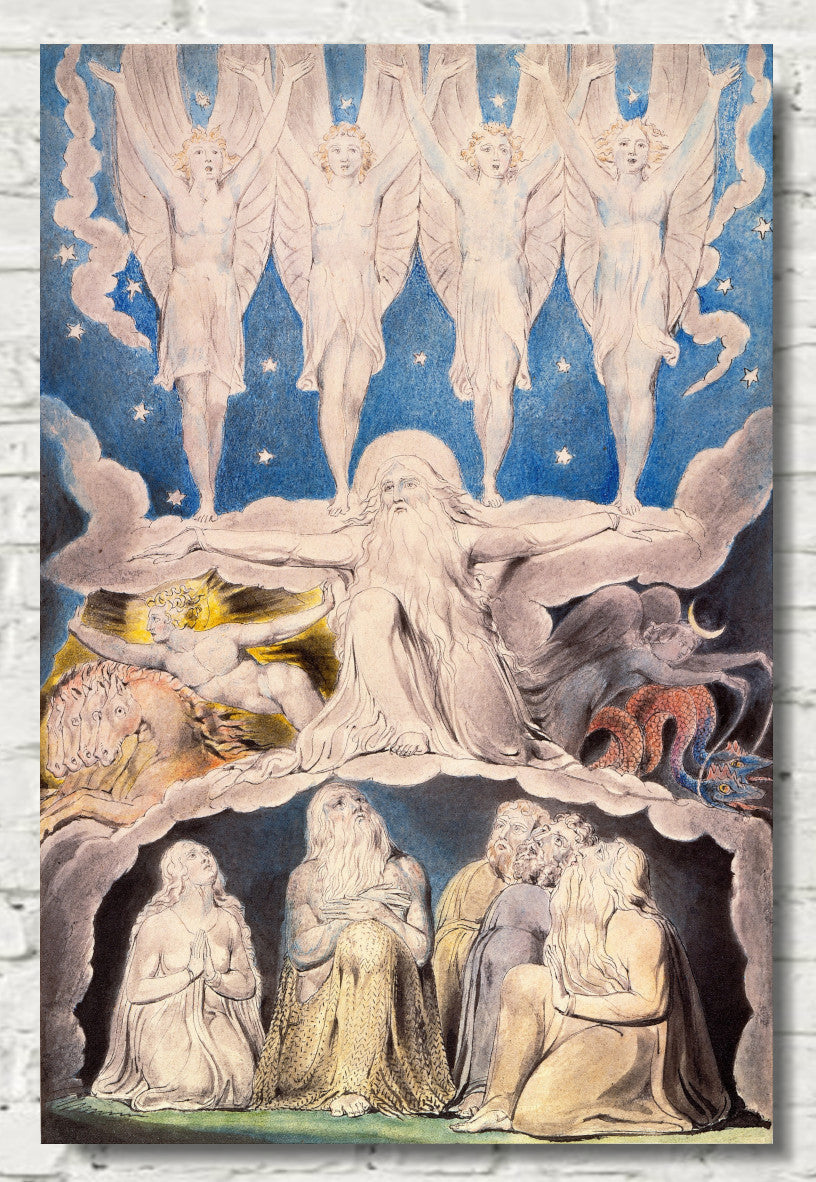

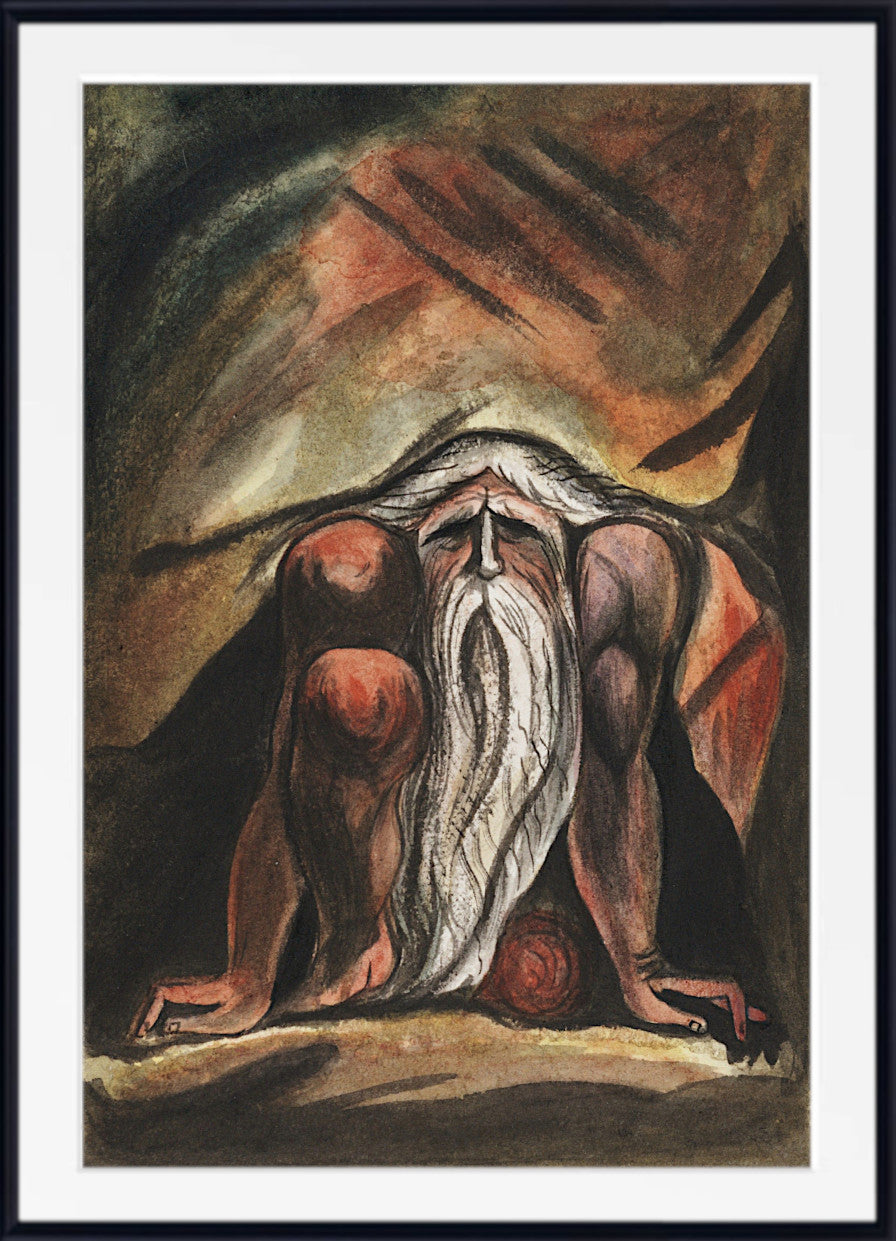

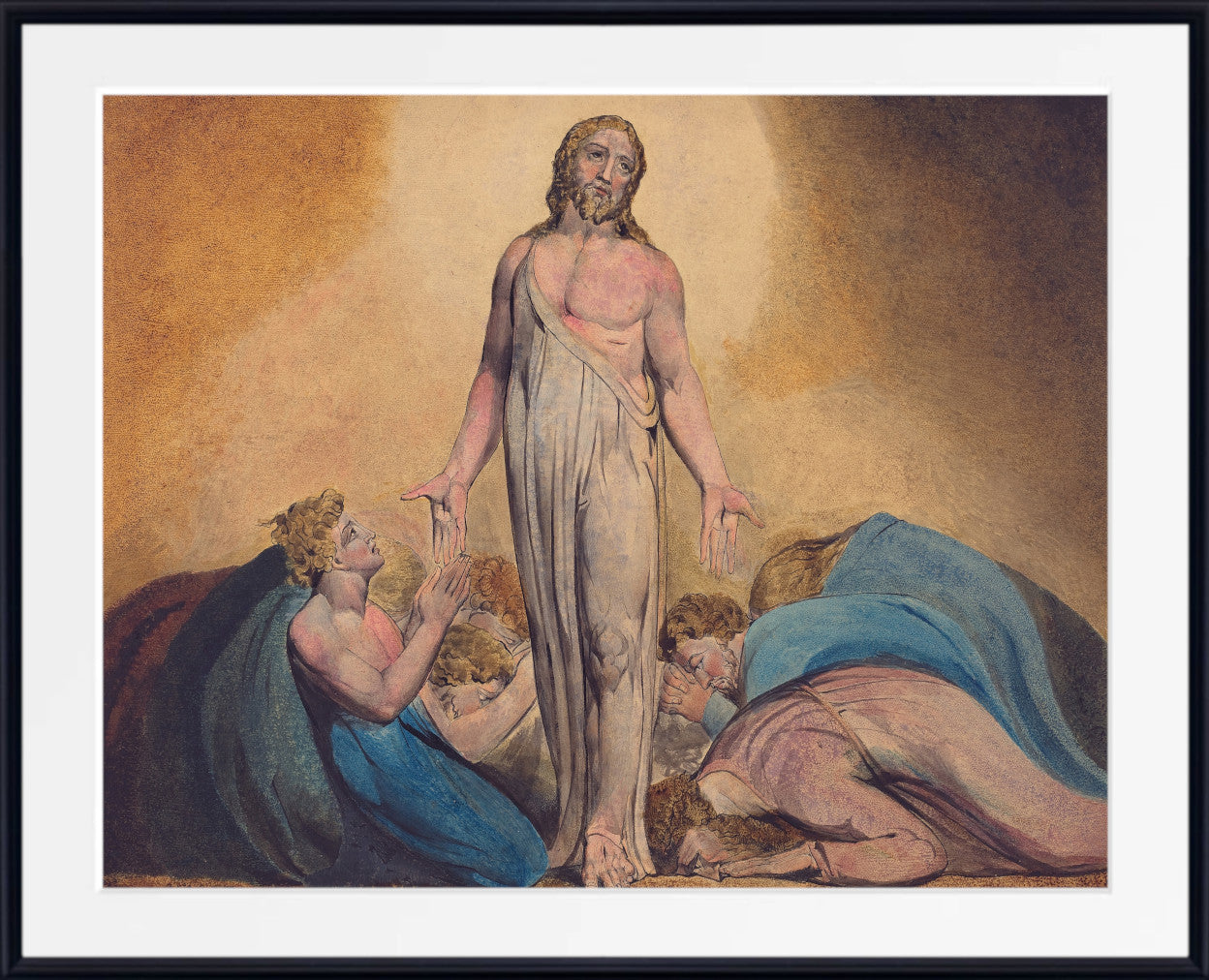

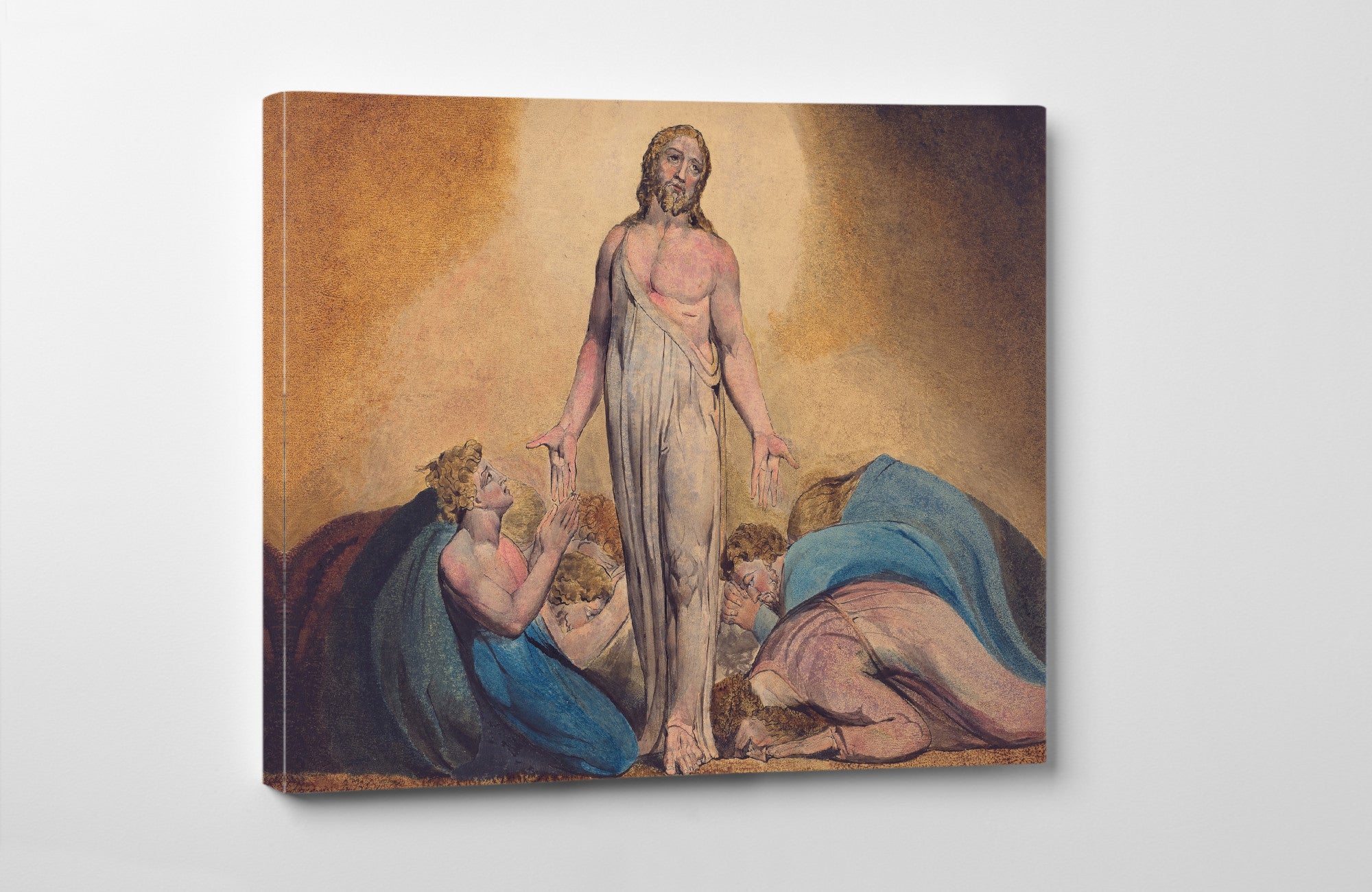

Even though he is probably still more well-known as a poet than as an artist, William Blake's life and work serve as a model for how we think of contemporary artists today. His work was supported by a small, zealous group of supporters despite being overlooked by his peers and marginalized by the academic institutions of his time. Blake lived a life of relative poverty as a result of his lack of commercial success, enslaved to a highly individual, sometimes iconoclastic, imaginative vision. Blake created a mythical universe through his prints, paintings, and poems that matched the complexity and depth of Dante's Divine Comedy but also reflected contemporary culture and politics, like Dante's. Blake was poor and somewhat unknown when he died in a small London house in 1827; He is now recognized as a model for the avant-garde artists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, whose creative spirit is in opposition to the culture's predominant mood.

William Blake's portrait in profile, by John Linnell

William Blake was born into a respectable working-class family in London's Soho neighborhood. James Hermitage made a living as a stocking and glove salesman, and Catherine Hermitage cared for the couple's seven children, two of whom perished in infancy. William was a strong-willed boy who was an obvious genius from a young age. He frequently skipped school to wander the London streets or copied drawings of Greek antiquities; Moreover, he developed an early fascination with poetry after being influenced by Raphael and Michelangelo's works. William had a happy childhood, but when he was eight, he started having visions. He said he saw angels on trees or wings that looked like stars. Blake's parents encouraged his artistic ambitions by enrolling him in the Henry Par drawing academy, a prestigious preparatory school for young artists at the time, when he was ten, despite being troubled by his stories.

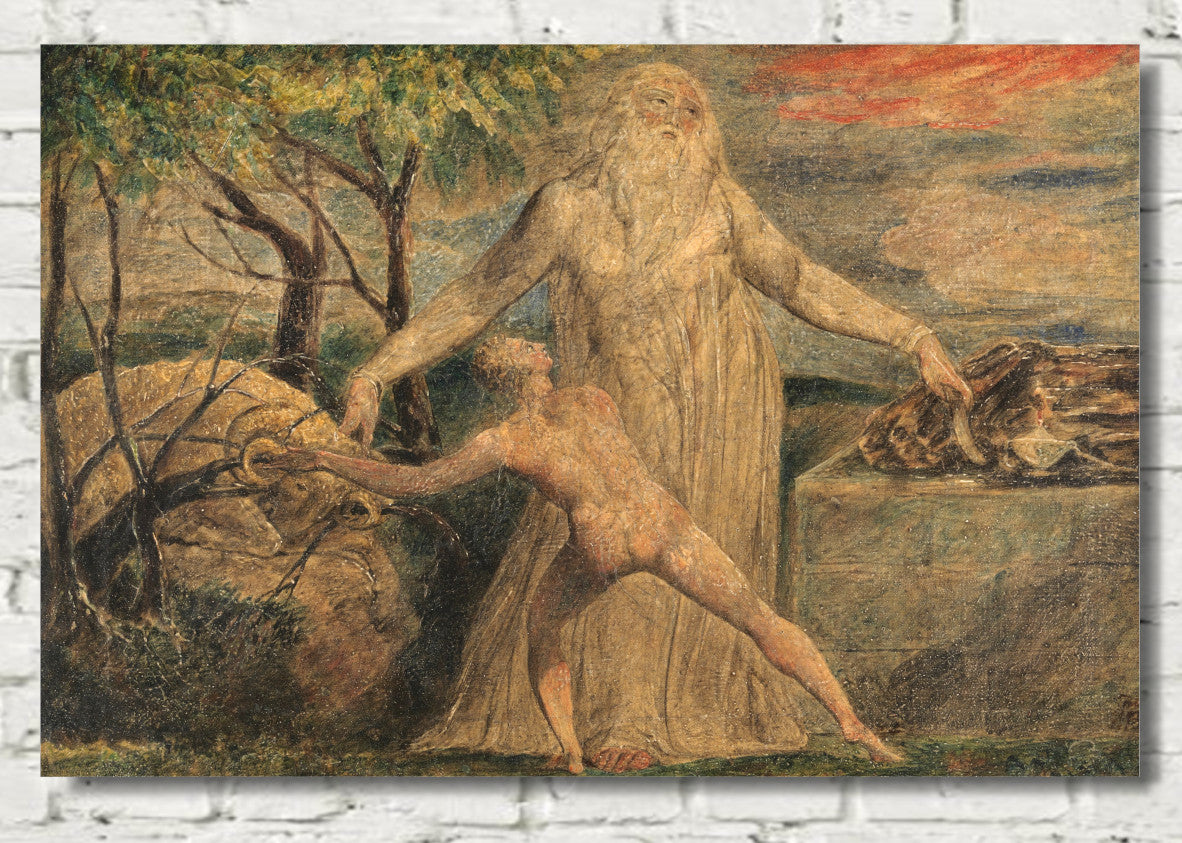

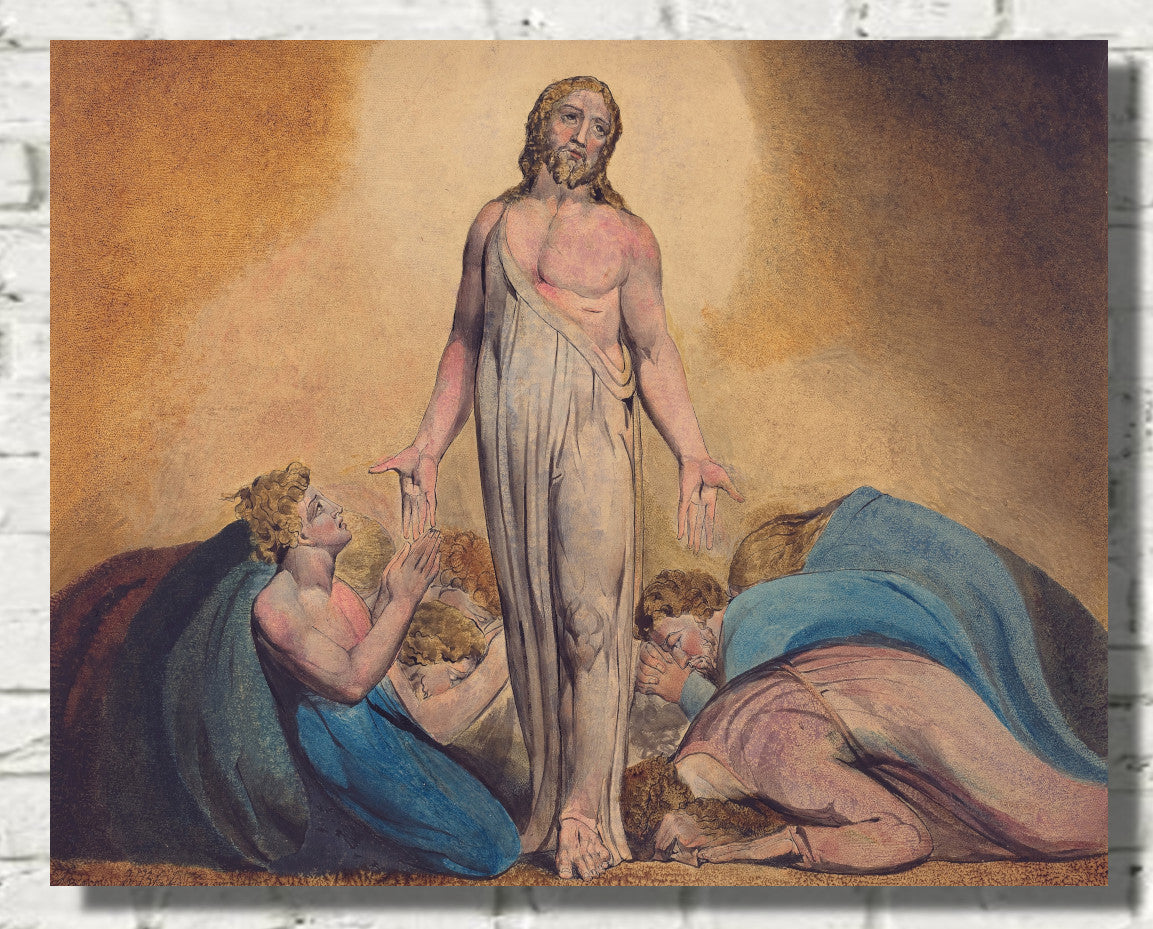

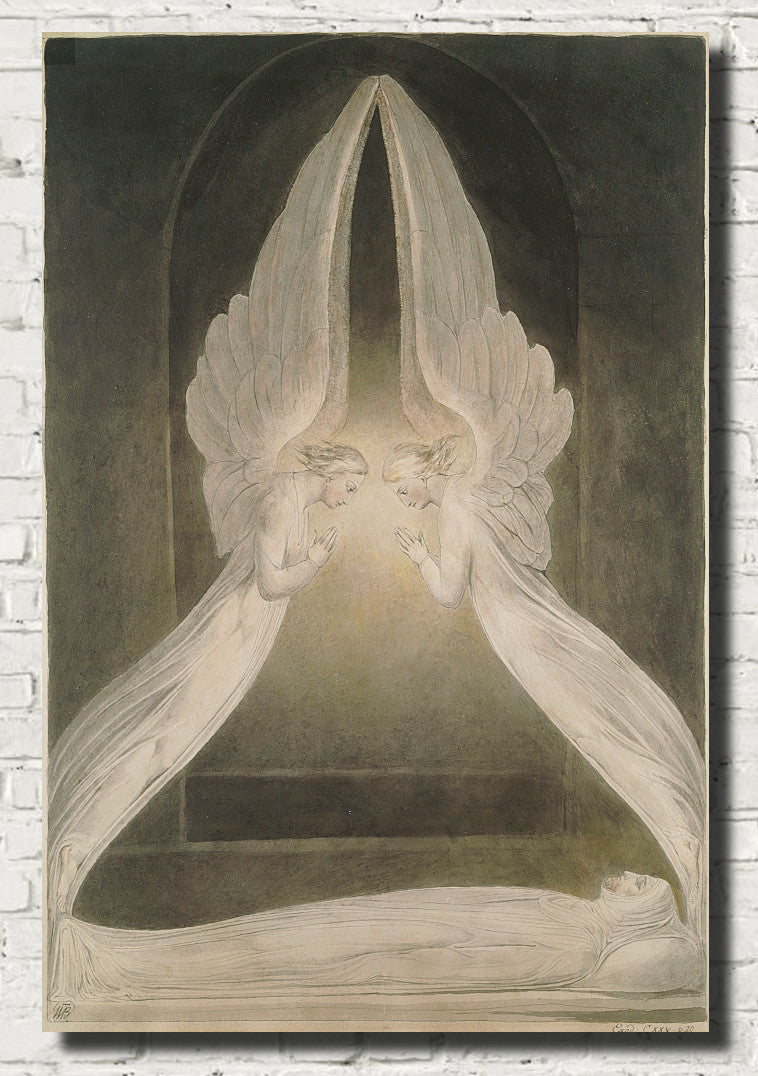

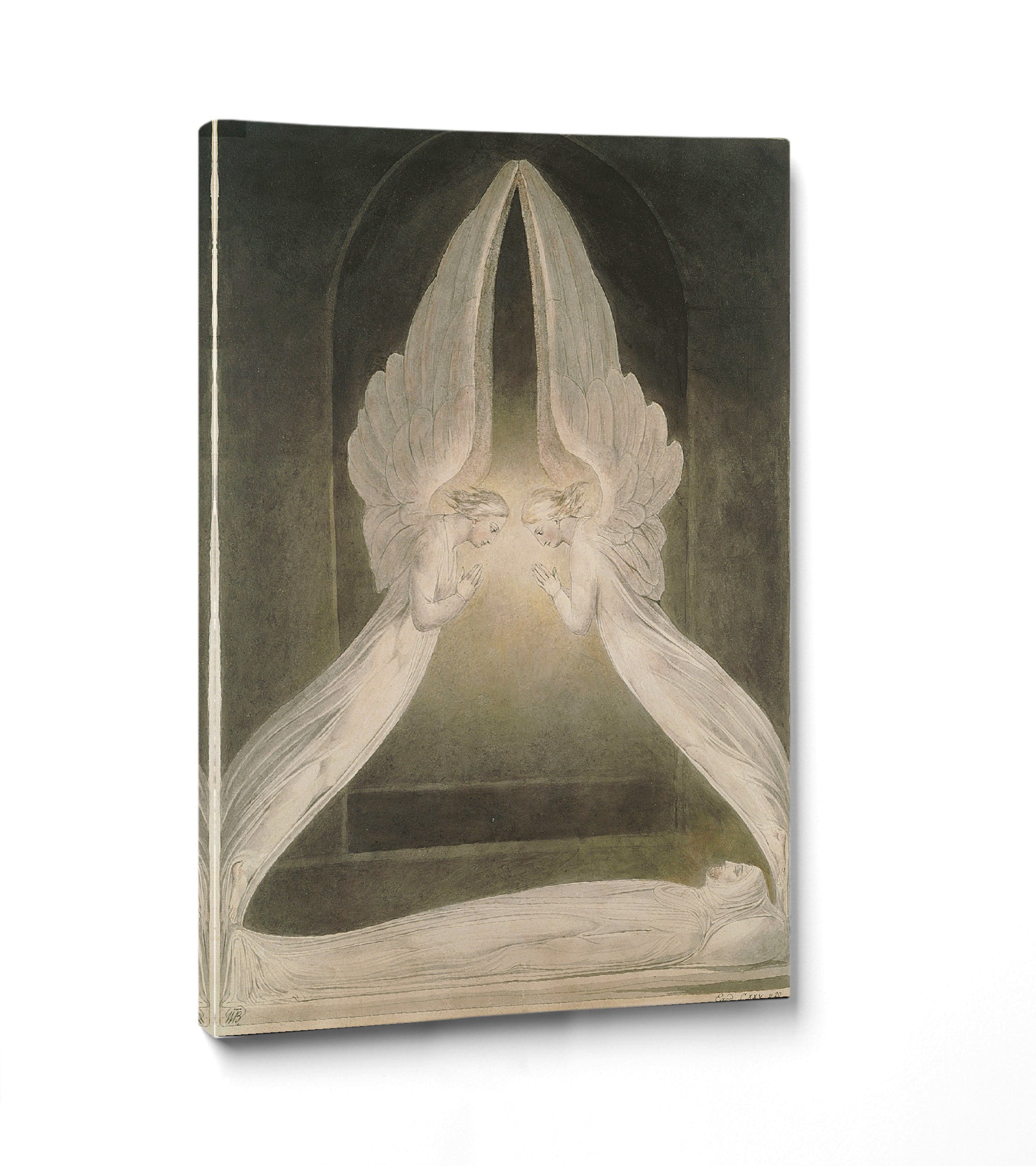

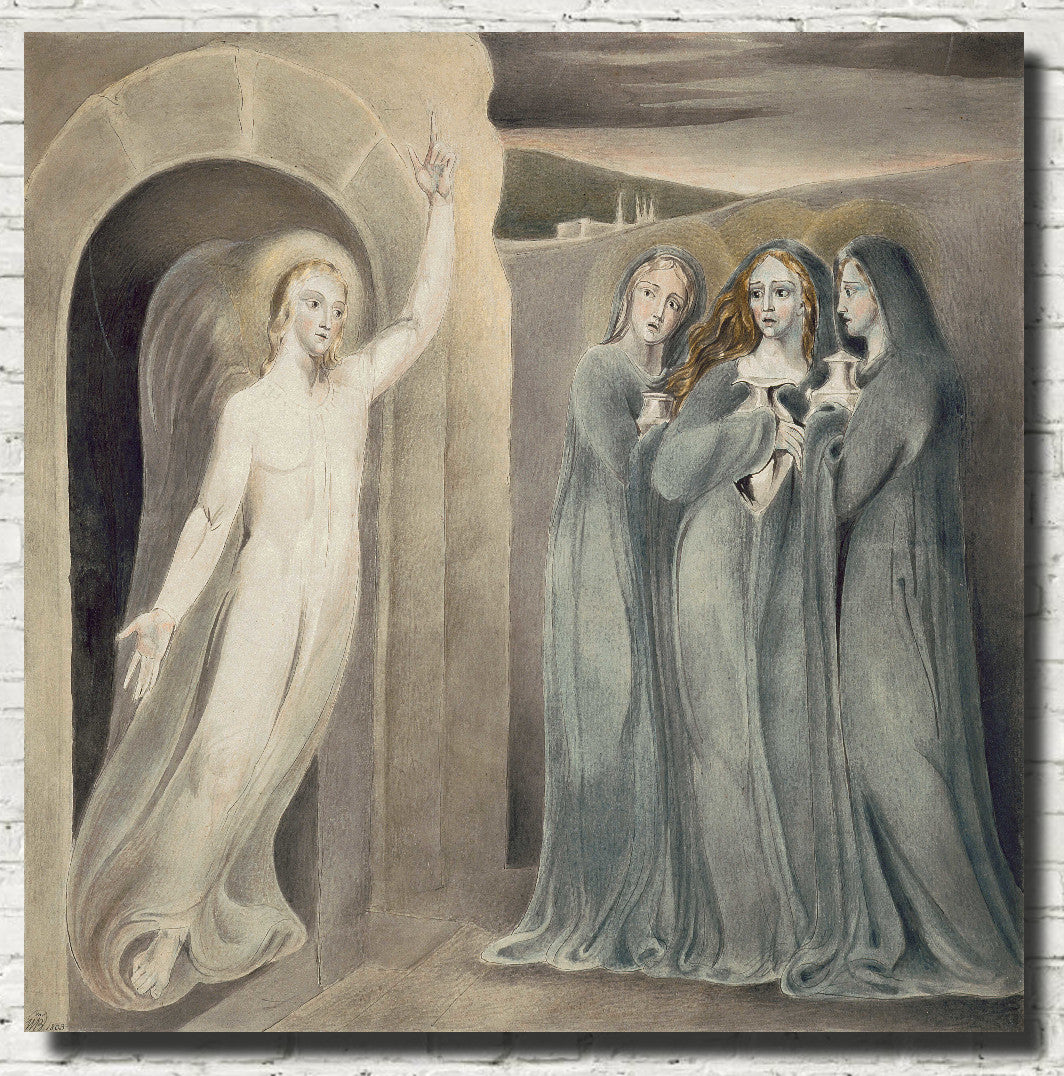

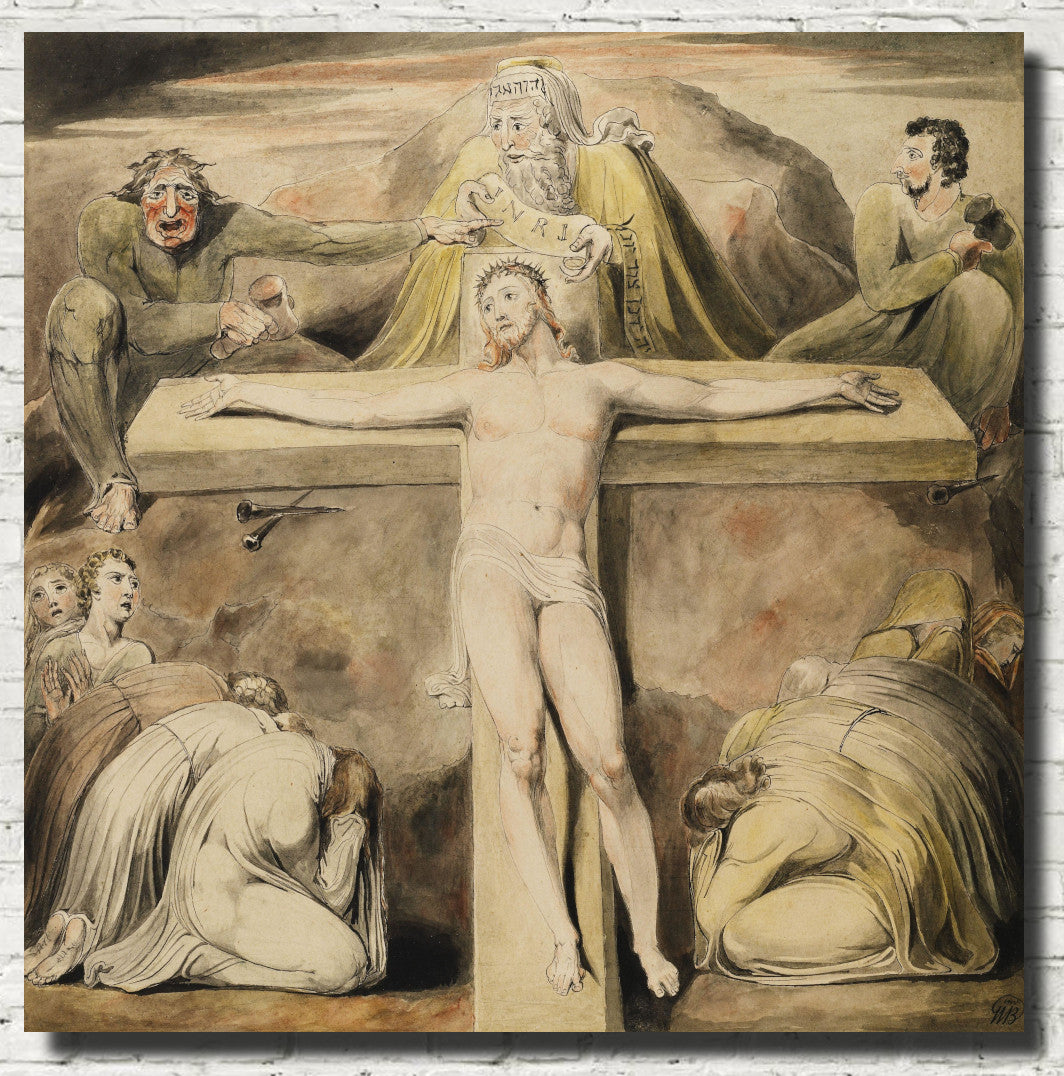

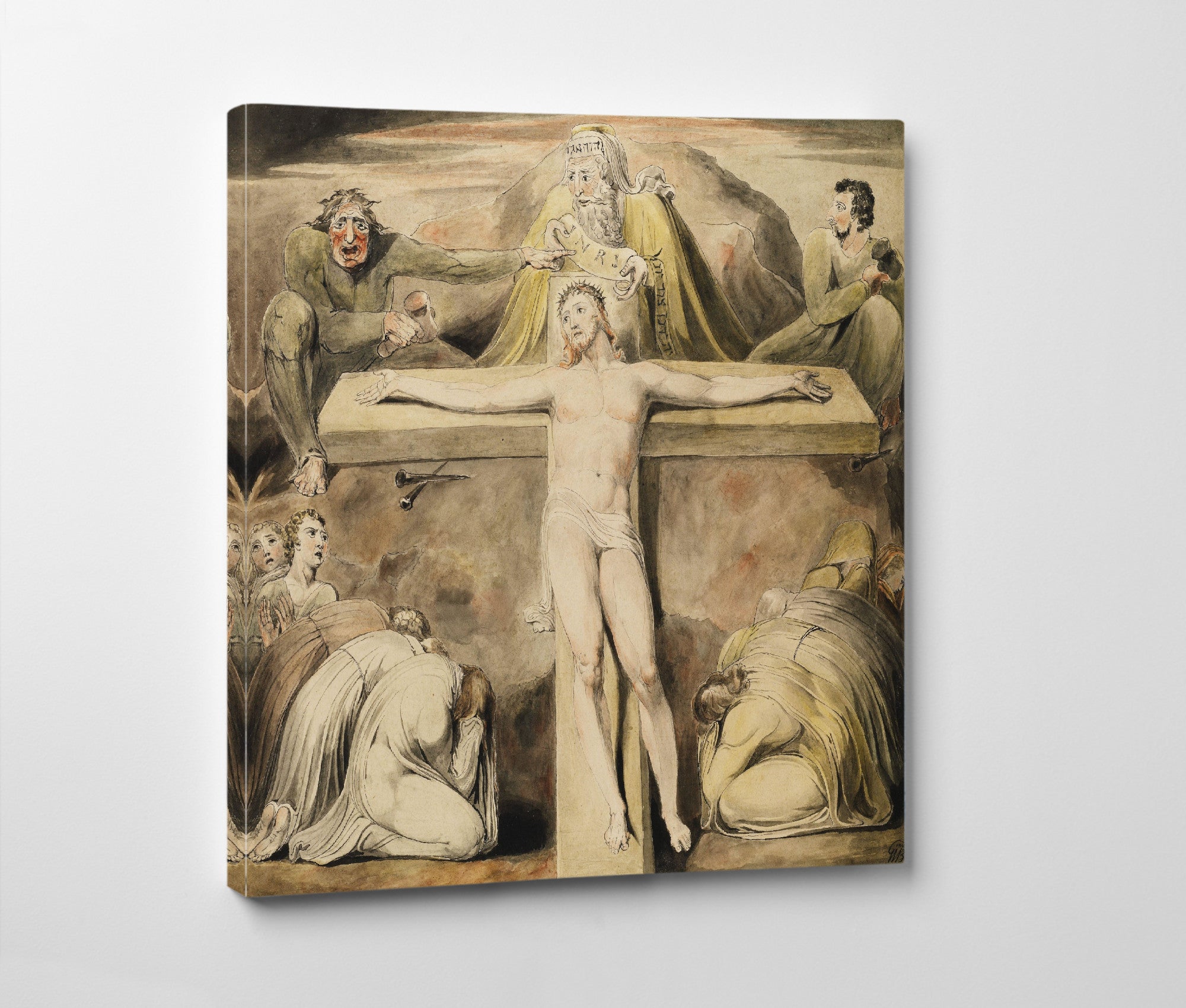

Christ Nailed to the Cross, William Blake

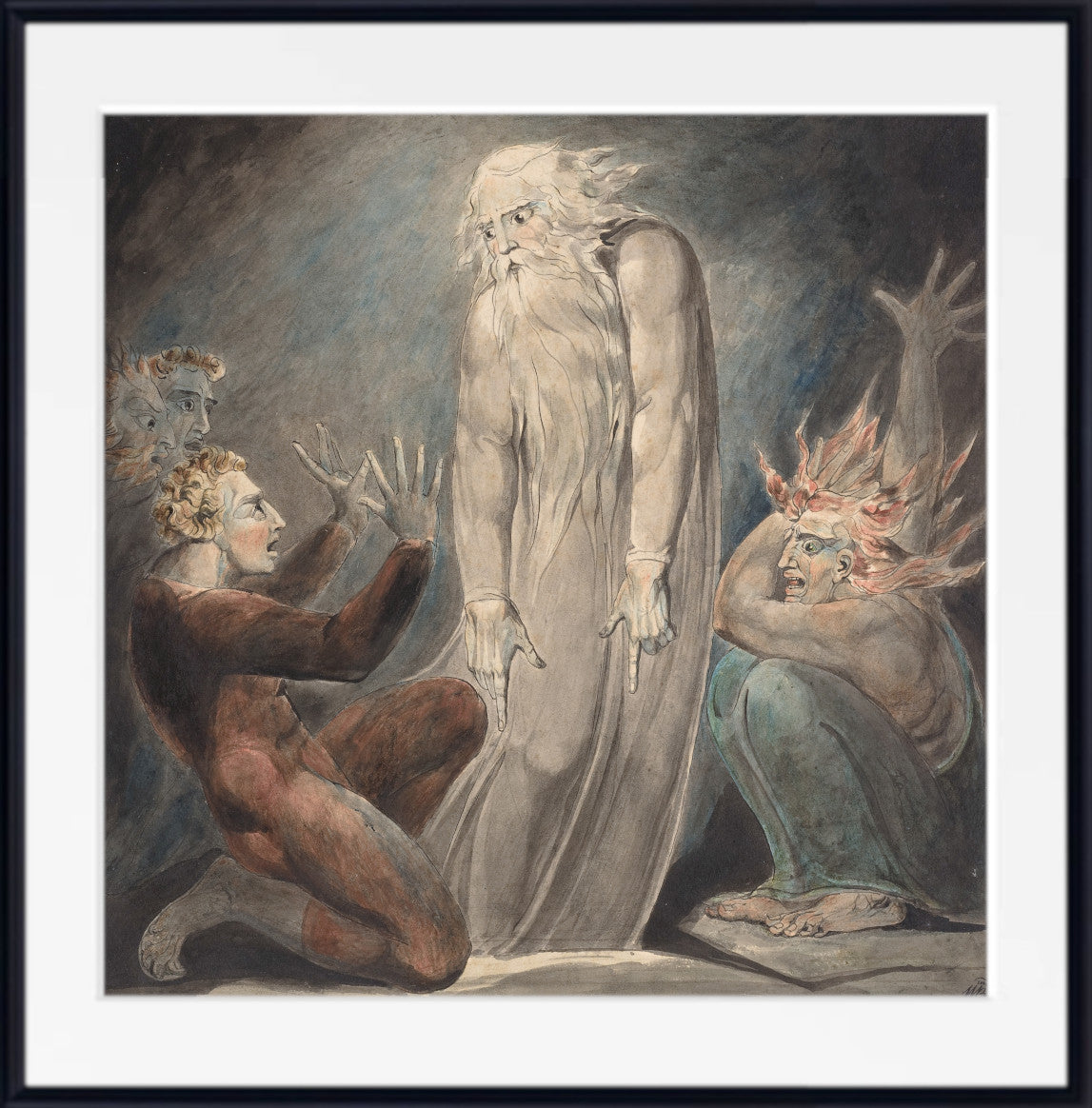

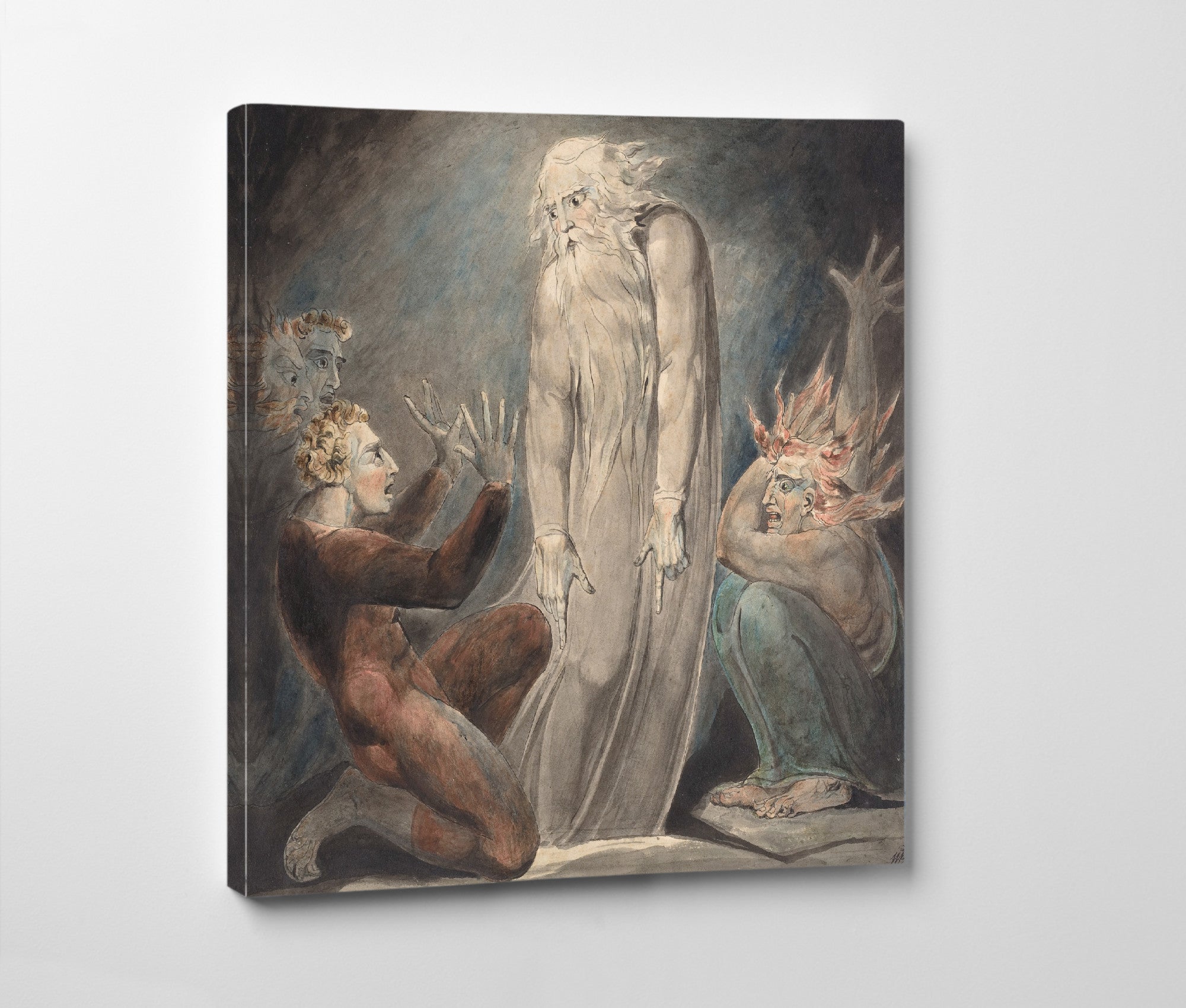

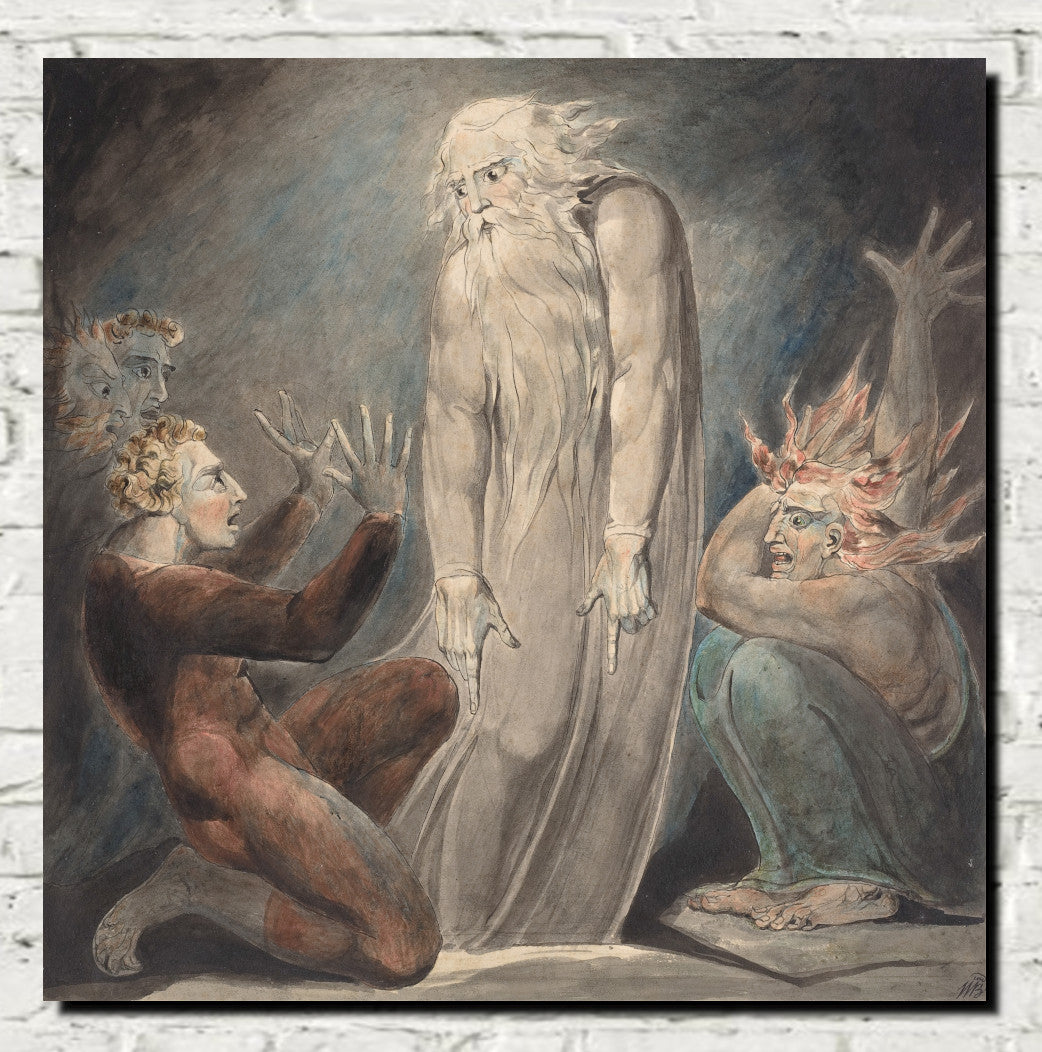

The Ghost of Samuel Appearing to Saul, William Blake

William Blake - Early Career

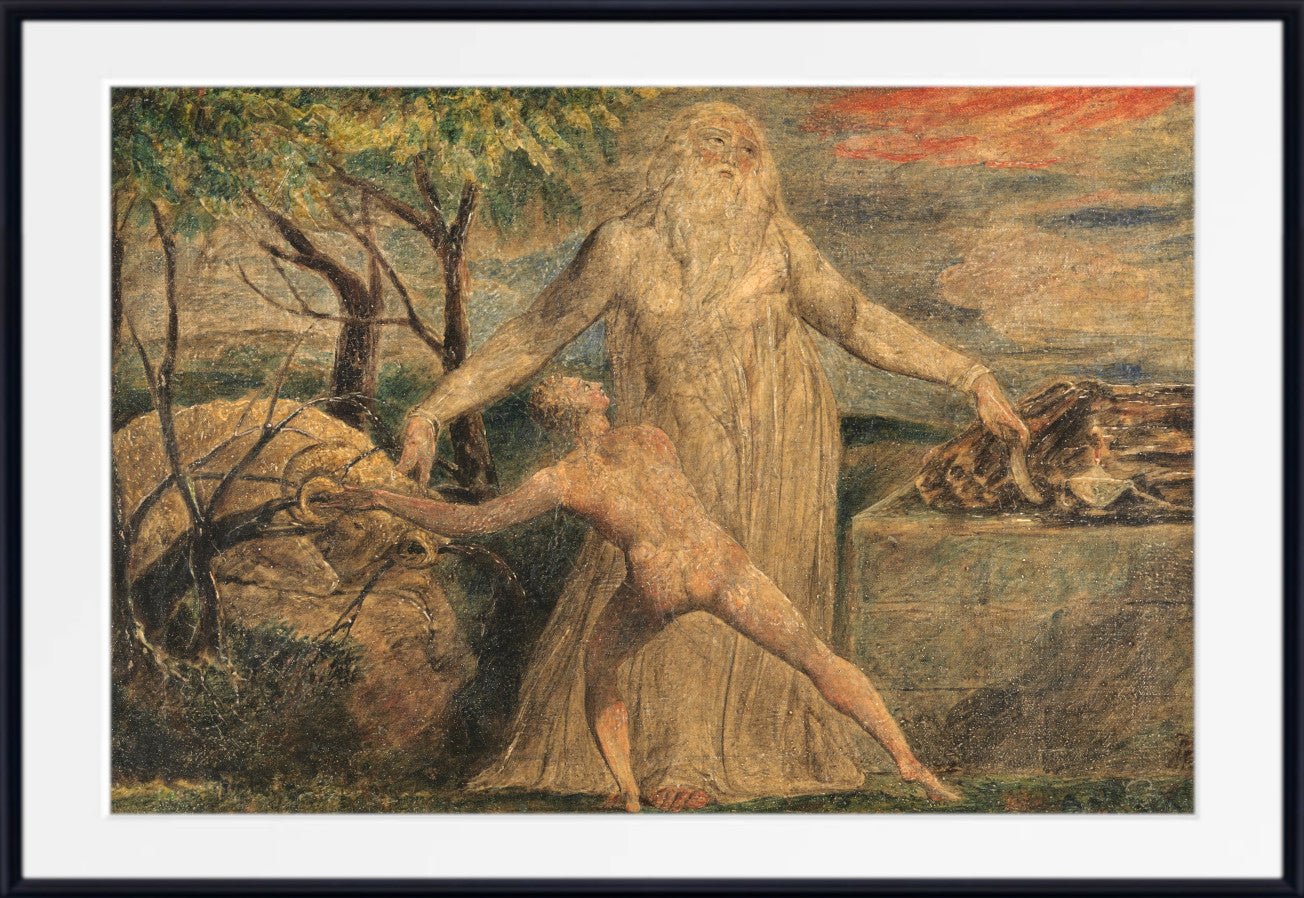

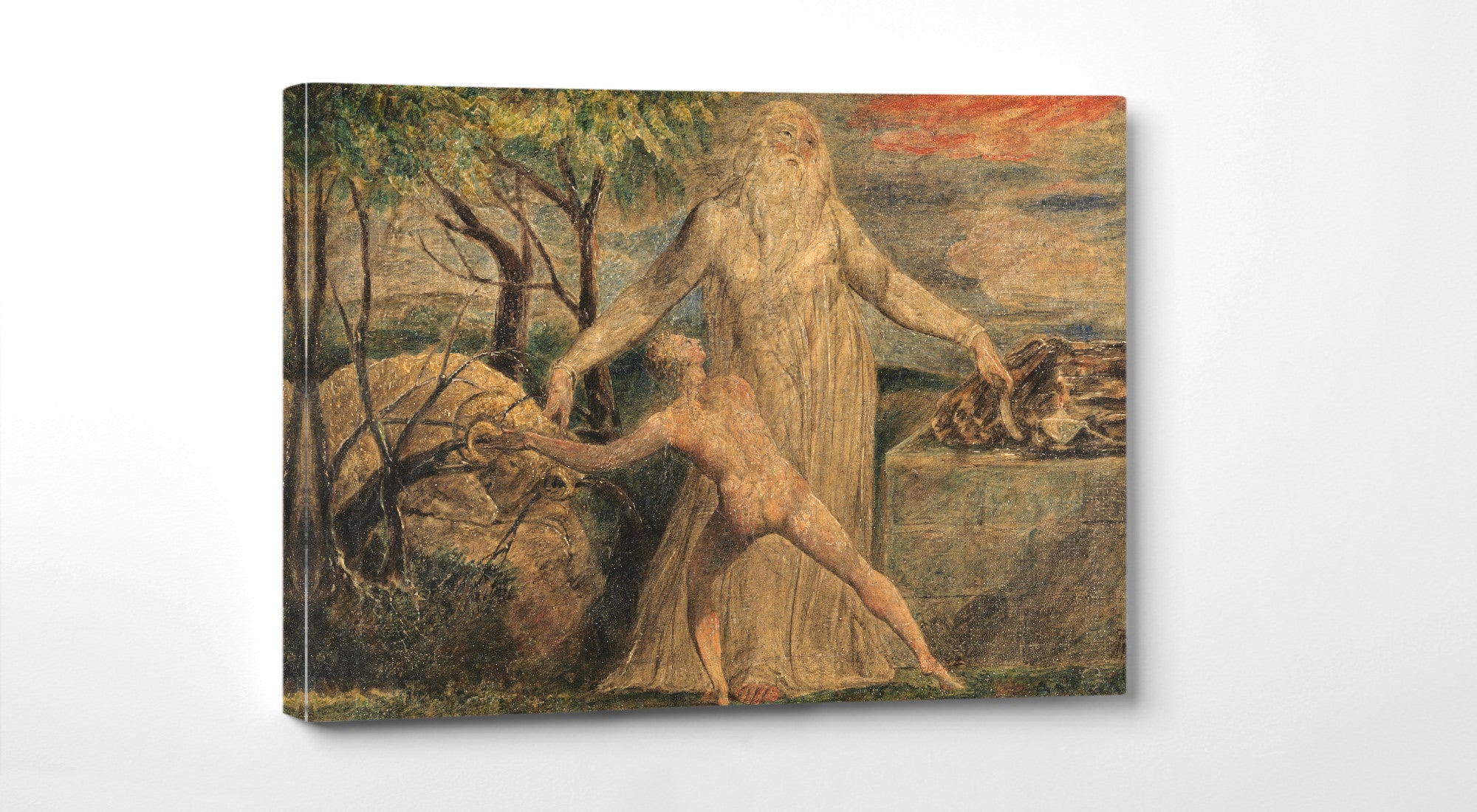

Blake was forced to leave the drawing academy after four years because it was too expensive. He was supposed to work as an apprentice for a master engraver, but the story goes that when his father took him to meet William Ryland, who was his potential employer, the young Blake said, "It looks as if he will live to be hanged!" a prediction that, oddly, came true years later. William was eventually given a five-year apprenticeship by Society of Antiquaries engraver James Basire. Blake valued his training with Basire, which influenced his work greatly: particularly his numerous drawings of Gothic structures made on-site. The young engraver studied art in his spare time, particularly Raphael, Michelangelo, and Dürer. According to art historian Elizabeth E. Barker, Blake believed that Dürer had created "timeless, 'Gothic' art, infused with Christian spirituality and created with poetic genius." Blake left his apprenticeship when he was 21 and enrolled at the Royal Academy. His time there was brief, in any case, supposedly in light of the fact that he scrutinized the tasteful precepts of the president Sir Joshua Reynolds, depicting the Foundation as a 'squeezed creative climate'. Blake started out working as a commercial engraver for a variety of publications, including well-known titles like Don Quixote. "That his 'Genius or Angel' was guiding his inspiration to the fulfillment of the'purpose for which alone I live, which is [...] to renew the lost Art of the Greeks," Blake wrote to his friend George Cumberland, one of the founders of the National Gallery, in 1799, according to poet and Blake scholar Kathleen Raine. Such a statement already demonstrates Blake's admiration for Greek art and his understanding of the connection between art and spirituality. However, it is important to note that the spiritual guides he claimed guided his artistic vision never led him into organized religion: He had never been to church. Blake met, courted, and married Catherine Boucher, the daughter of a local grocer, in August 1782, when he was 25 years old. Blake spent a lot of time teaching Catherine how to read, write, and draw, partly because the couple didn't have kids. Meanwhile, Catherine helped Blake design things. Poetical Sketches, Blake's first collection of poetry, was published in 1783. The Blakes' finances were stable despite poor sales because William's popularity as an engraver was growing. Blake and his friend James Parker opened a store with the money his father had given them. In the small pamphlet "There is No Natural Religion," which was published in 1788 and contained his illustrated poetic and religious credo, he used his method of "illuminated printing" for the first time. Robert, Blake's brother, passed away around this time, probably from tuberculosis, after a long and difficult illness. Blake's belief that Robert's spirit inhabited him and inspired him through visions and apparitions grew as a result of his death.

William Blake - Mature Period

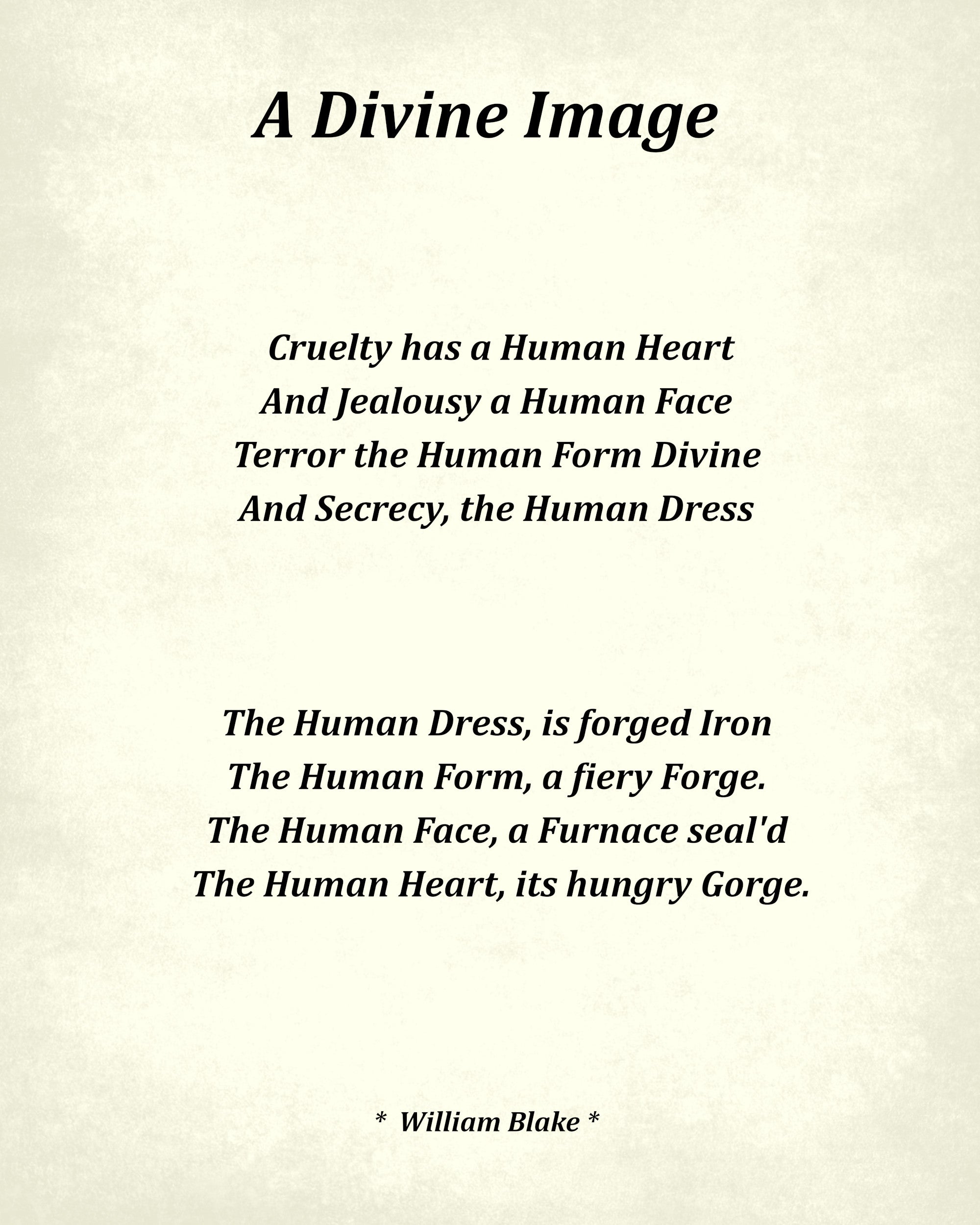

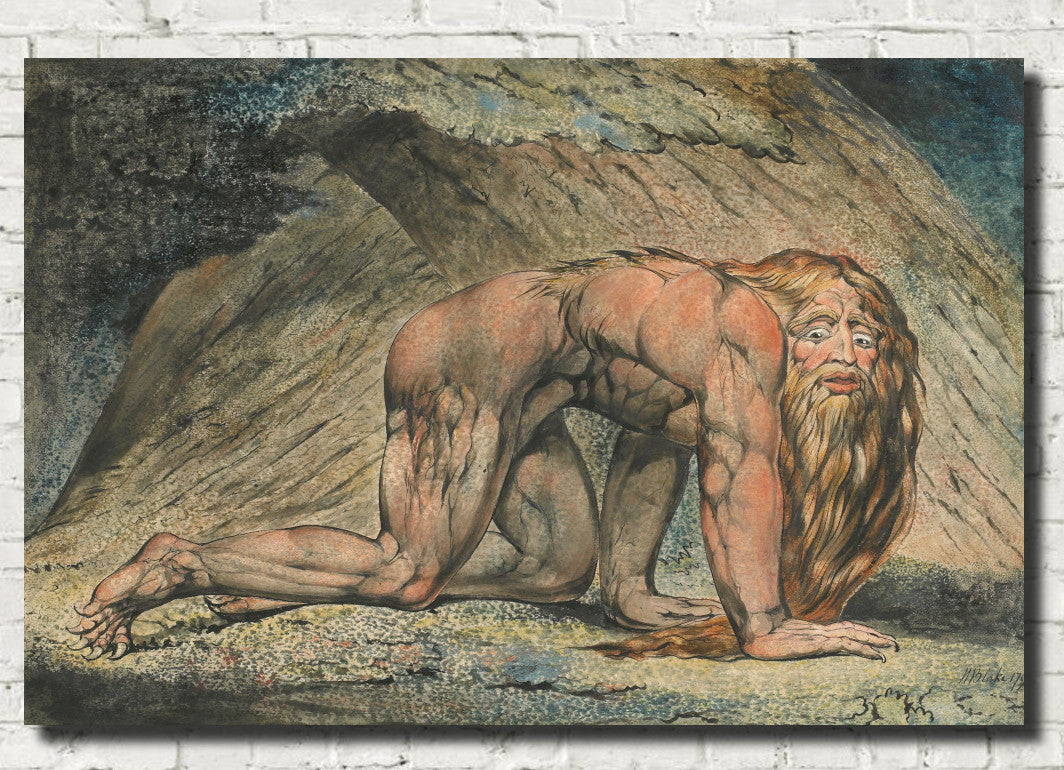

Blake started a series he called "Large Color Prints" in 1795 that depicted themes from Shakespeare, Milton, and the Bible. However Blake was never a disengaged figure - he mingled generally, and appended himself to different social circles in London, through companions like Henry Fuseli and James Barry - Raine takes note of that he was not an "simple man socially", being "glad, factious and viciously went against to current style, in his specialty and his thoughtful and strict thoughts the same". Blake, without a doubt, held radical political and religious views and was opposed to social conformity. He was a kind of Platonist who thought that the scientific view of the universe that was promoted by the Enlightenment was the "enemy of life." However, the journalist Peter Blake says that he was also an "artist with public ambitions," so he wasn't a hermit like he was later. Blake met Thomas Butts the year he started working on the Large Color Prints. Butts would become Blake's main patron for several years and commission many of his works. "Promising," as Raine puts it, "only to buy from him whatever he should paint," Butts left Blake to pursue his private visions and impulses. Blake wrote at the time, " I think I see things that are better than anything I've ever seen. My work is appreciated by my employer, and I have a one-guinea order for fifty small pictures, which is better than just copying another artist's work." Blake was also supported for a time by the poet William Haley, who hired him to complete a project in 1800. However, Blake quickly lost interest in the project and fell into a depression while residing at Haley's country estate in Felpham because he couldn't "sacrifice his integrity as an artist for profit." The two poets' relationship came to an abrupt end, and Haley referred to Blake as his "spiritual enemy." Around this time, Blake found it increasingly challenging to earn a living. Despite his connections to the London art scene and his ongoing commissions from Butts, engraving work ceased. Blake was not a member of the art "establishment," unlike his friends Barry and Fuseli, who held positions at the Royal Academy. As a result, he was never given the opportunity to carry out large-scale public works. He wrote in "The Invention of a Portable Fresco," a catalogue for his one and only public exhibition, in 1809 that creating portable frescoes might be a good way to convince "visionless" patrons of the quality of his work. He lamented his lack of public commissions in England. Blake's problems got worse when he started having more and more nightmares and hallucinations, which made people think he was insane: He is known to have made the public claim, perhaps with some justification, that he revised the works of Dürer and Michelangelo on the advice of the artists after communicating with them in visions. Blake's mysticism drew him into ever more solitary patterns of existence because of his proud behavior and strongly held beliefs. He was never humble about his work, and he once wrote to Butts, "The works I have done for you are equal to Carrache or Rafael." Despite this, he continued to produce a huge body of work, fueled by his attention to what he called "miracles" and a firm belief in the power of imagination. Once, Blake said: I am aware that this world is one of vision and imagination. I paint everything I see in this world, but no two people see things the same way. Throughout his mature years, he frequently claimed to be in contact with historical and mythical figures like the Virgin Mary or to be supported in his work by Archangels. "The bitterest irony in the story of Blake's failures and humiliations is that he was never unknown," according to Kathleen Raine. On the other hand, he knew all of the most well-known engravers and artists of his time and lived in the center of London's art scene. Nevertheless, he failed where they succeeded, being overrun by men of lesser abilities and overlooked by friends for life.

William Blake - Later Years

Blake spent almost all of his life in the neighborhood of his birth, Soho, and traveled very little. However, despite his lack of worldliness, he turned into a highly educated man by collecting a large number of classical art prints, for instance. Yet again following quite a while of destitution, he had to sell his print assortment, however in 1818 Blake's monetary fortunes turned when he met John Linnell, the one who might turn into his second extraordinary supporter. Through his commissions and purchases, Linnell provided Blake with financial security in his later years. He also introduced Blake to a group of artists known as The Ancients, or The Shoreham Ancients, who had come together because they were all impressed by Blake's work. Like Blake, this gathering rejected 'present day' ways to deal with craftsmanship and style, and had a comprehensively Non-romantic perspective of the universe. Blake suddenly became regarded as a "teacher" and leader as he neared the end of his life. In fact, Samuel Palmer, one of the Ancients with the most talent, is generally thought to have inherited Blake's vision and technique. Blake moved into a house close to the Strand around 1820 and spent his days engraving in a small bedroom. He accepted a commission from Linnell in 1821 to illustrate The Book of Job at the age of 65. Samuel Palmer wrote that Blake was "moving apart, in a sphere above the attraction of worldly honors" when he wrote about him around this time. Palmer continued, "but confer it, not accept it." By his conversation and the influence of his genius, he elevated poverty and made two small Fountain Court rooms more appealing than the princes' threshold." Another friend from this time, diarist Henry Crabb Robinson, wrote in an 1826 letter that anyone who met Blake saw him as "at once the Maker, the Inventor; one of very few in any age group: a perfect companion for Dante." Despite Blake's age and relative poverty, Robinson described him as embodying "energy" himself and releasing an atmosphere "full of the ideal" all around him. William Blake, 70, passed away in August 1827. He was working on a set of illustrations for Dante's Divine Comedy at the time of his death, which are now regarded as some of his best work. It is expressed that upon the arrival of his demise, as he worked quickly on these pictures, he declared to his significant other: " Stay! Stay where you are! You have always been my angel: I'll sketch you!" After a few hours, he died: The drawings have vanished. Richard Holmes, a critic of art, says that when Blake died, "he was already a forgotten man." Over the course of 30 years, sales of his engravings and painted poems barely reached 20 copies. Blake, on the other hand, "died like a saint...singing of the things he saw in heaven," according to George Richmond, an artist associated with The Ancients.

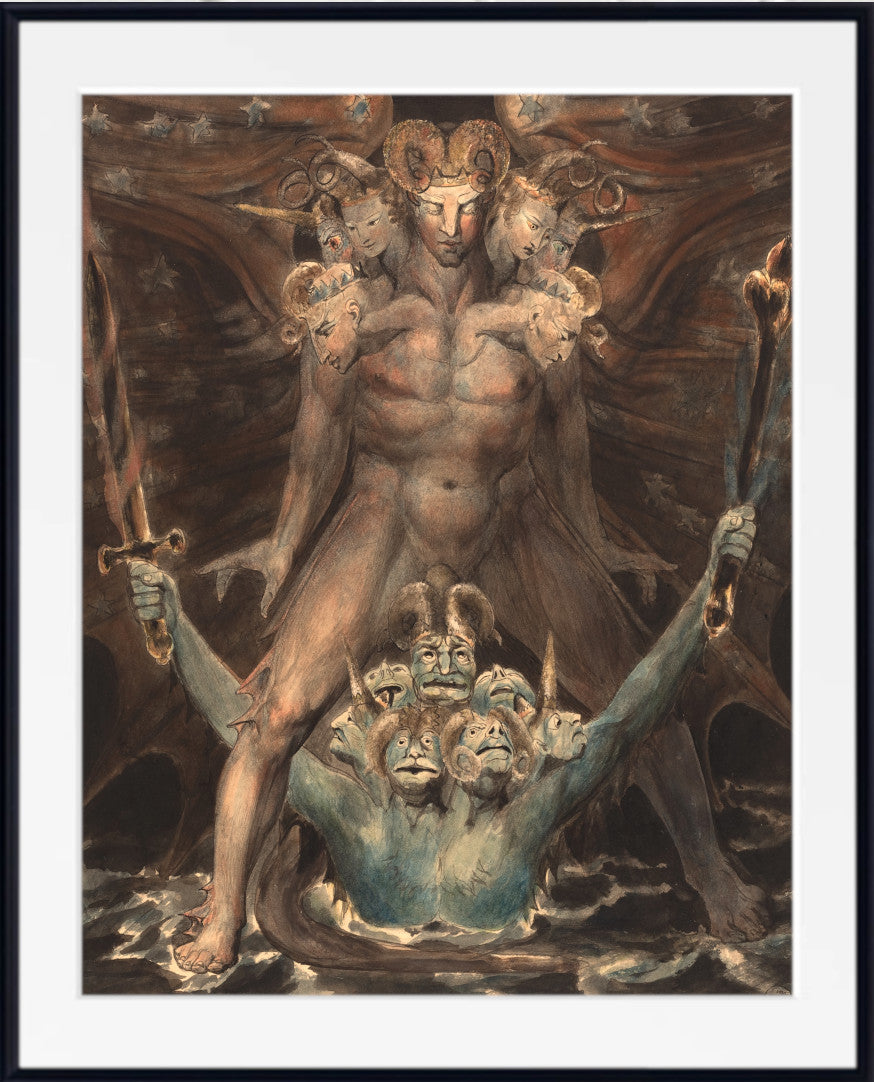

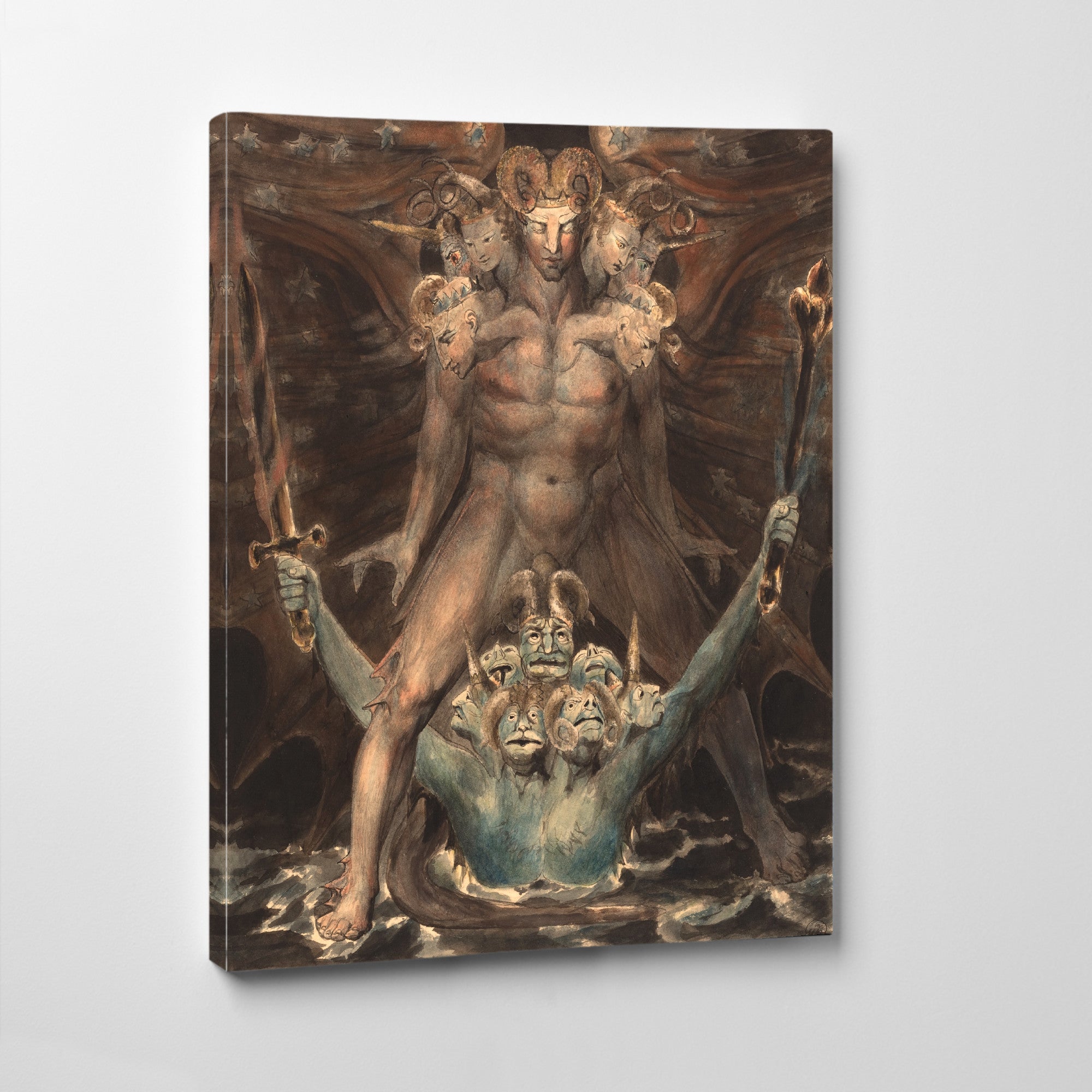

The Great Red Dragon and the Beast from the Sea, William Blake

The schismatics and sowers of discord- Mahomet, William Blake

Blake - The Legacy

William Blake is generally regarded as one of the great artistic polymaths. He is not only one of the best English language poets but also one of the most revolutionary visual artists in Britain: He is called "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced" by critic Jonathan Jones. Blake's work is also remembered for its intricate and one-of-a-kind philosophical and religious schemas: Blake, in contrast to his Romantic contemporaries like John Constable and J.M.W. Turner, turned inside out and created an imaginative world based on the Bible and other religious and literary texts, taking his audience on what Elizabeth E. Barker refers to as "journeys of the mind." According to Kathleen Raine, Blake himself saw the works as "portions of eternity" in imaginative vision. "Fragments of worlds whose bounds extend beyond any of those portions their work embodied," she says, comparing him to Renaissance masters like Michelangelo, Dürer, Dante, and Fra Angelico—Blake's favorite artist—in his capacity to create all-enveloping imaginative realms that appear ex nihilo. Therefore, it is ironic that Blake was ignored by literary and artistic society during his lifetime. He was generally regarded as eccentric or insane because it was common knowledge that he claimed to work from visions; The full scope and significance of Blake's visions were only realized when the art critic Alexander Gilchrist, who was born a year after Blake's death, began the concerted study of his art and legacy, which led to the publication of The Life of William Blake in 1863. Gilchrist said that Blake's hallucinations were the result of a "special faculty" of imagination, and that his avowed connection to the spiritual world was evidence not of madness but of a kind of "mysticism." At the same time that Pre-Raphaelite artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti were responding to the clarion call of Blake's spiritual intensity, Gilchrist's writing provided a new context for the study of Blake's practice. In general, Blake's mystical and visionary works had a significant impact not only on the later stages of Romanticism in art but also on Pre-Raphaelitism, Symbolism, and even modernism. Blake has had a significant impact on literature as well: Blakean visions also had an afterlife in the abstract and psychedelic pop lyrics of the 1960s, particularly in Bob Dylan's post-beat dream sequences. Among the poets who were profoundly influenced by him were Walt Whitman, W. B. Yeats, and Allen Ginsberg. Blake's legacy can be found in all areas of high and popular culture today, including film, literature, music, and art. For instance, it is believed that his imagery served as inspiration for the illustrations in Lord of the Rings and other films about mythology.

Hecate, William Blake

William Blake Quotes

- It is easier to forgive an enemy than to forgive a friend

- If a thing loves, it is infinite.

- If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.

- Tyger! Tyger! burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry? - Those who restrain desire do so because theirs is weak enough to be restrained.

- The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing that stands in the way. Some see nature all ridicule and deformity… and some scarce see nature at all. But to the eyes of the man of imagination, nature is imagination itself.

- What is now proved was once only imagined.

- The imagination is not a state: it is the human existence itself.

- I must create a system, or be enslaved by another man’s. I will not reason and compare: my business is to create.

- The man who never alters his opinion is like standing water, and breeds reptiles of the mind.

- To generalize is to be an idiot.

- The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.

- In the universe, there are things that are known, and things that are unknown, and in between, there are doors.

- You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough.

- Eternity is in love with the productions of time.

- Love seeketh not itself to please, nor for itself hath any care, but for another gives its ease, and builds a Heaven in Hell’s despair.

- I was walking among the fires of Hell, delighted with the enjoyments of Genius; which to Angels look like torment and insanity.

- Truth can never be told so as to be understood and not be believed.

- He who kisses joy as it flies by will live in eternity’s sunrise.

- Throughout all eternity, I forgive you and you forgive me.

- Without contraries is no progression. Attraction and repulsion, reason and energy, love and hate, are necessary to human existence.

- He whose face gives no light, shall never become a star.

- My mother groaned, my father wept, into the dangerous world I leapt.

- Excessive sorrow laughs. Excessive joy weeps.