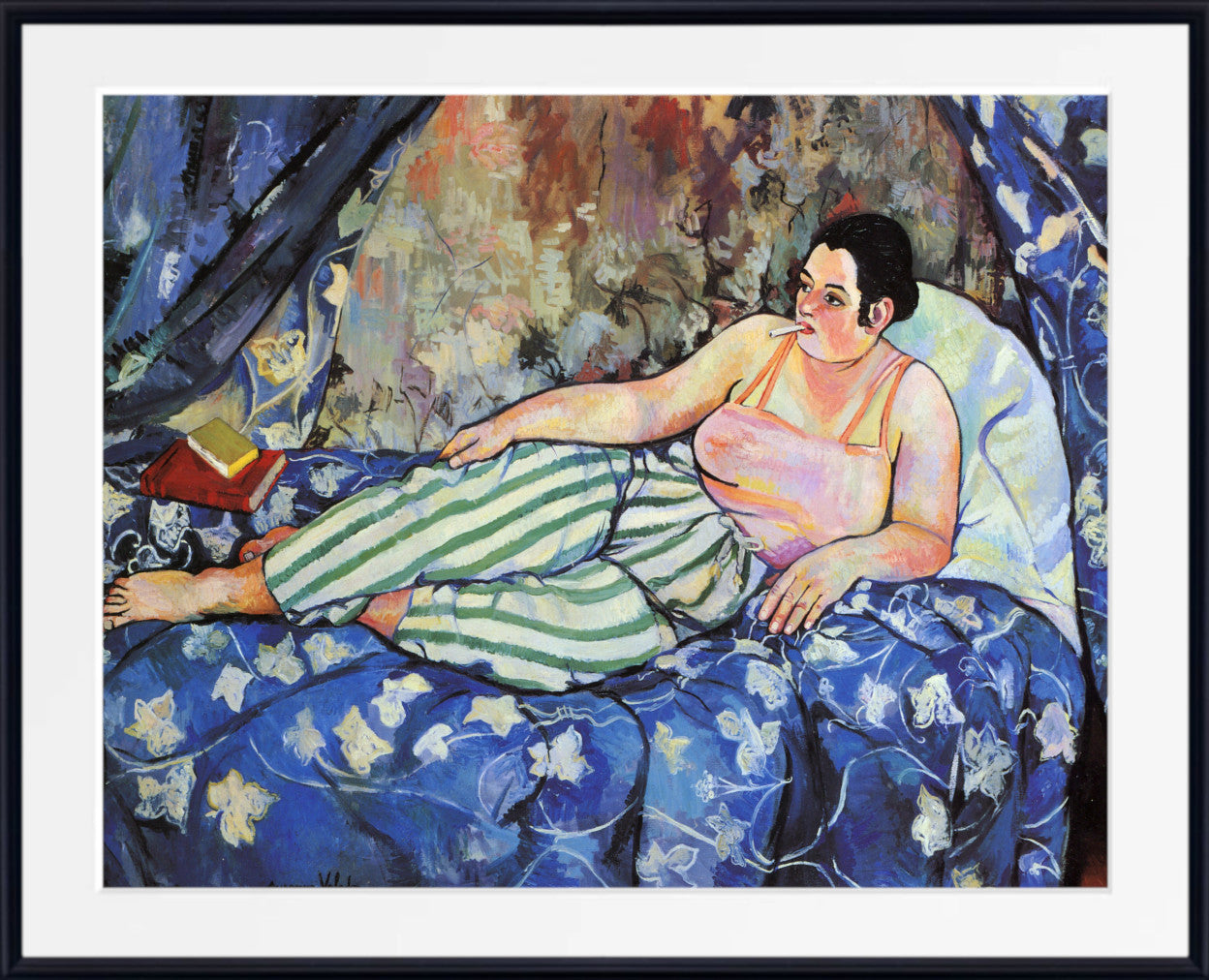

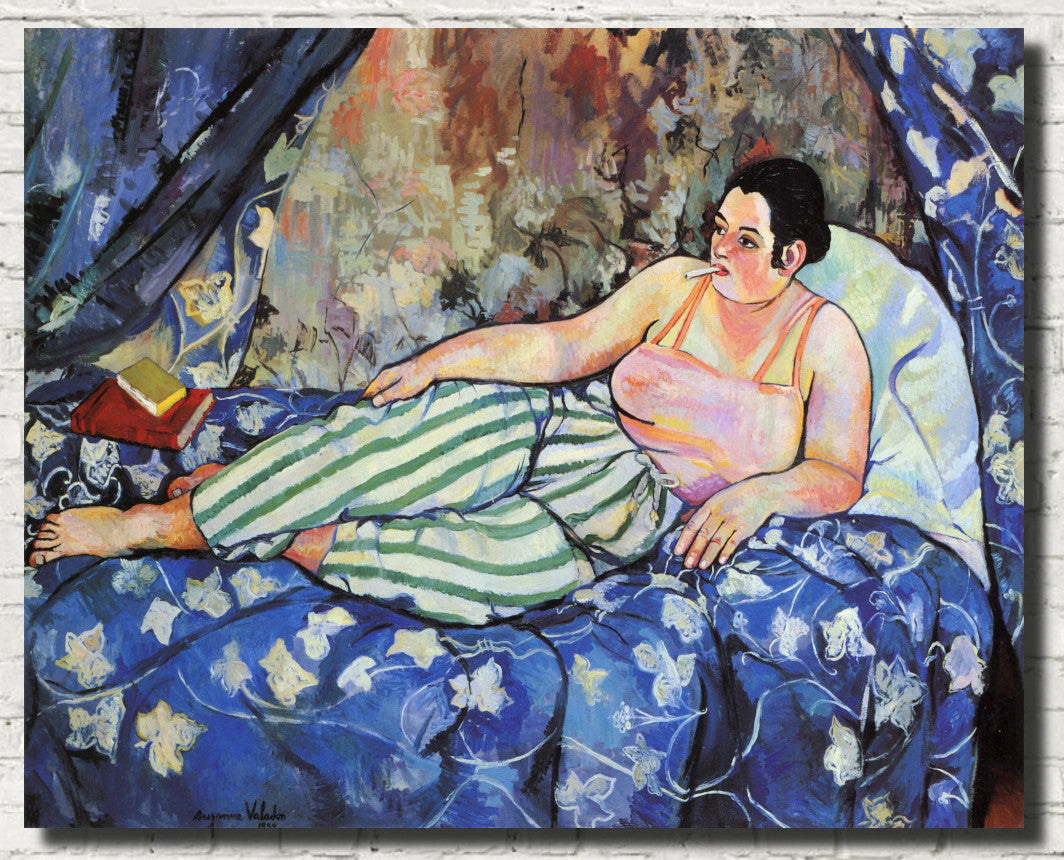

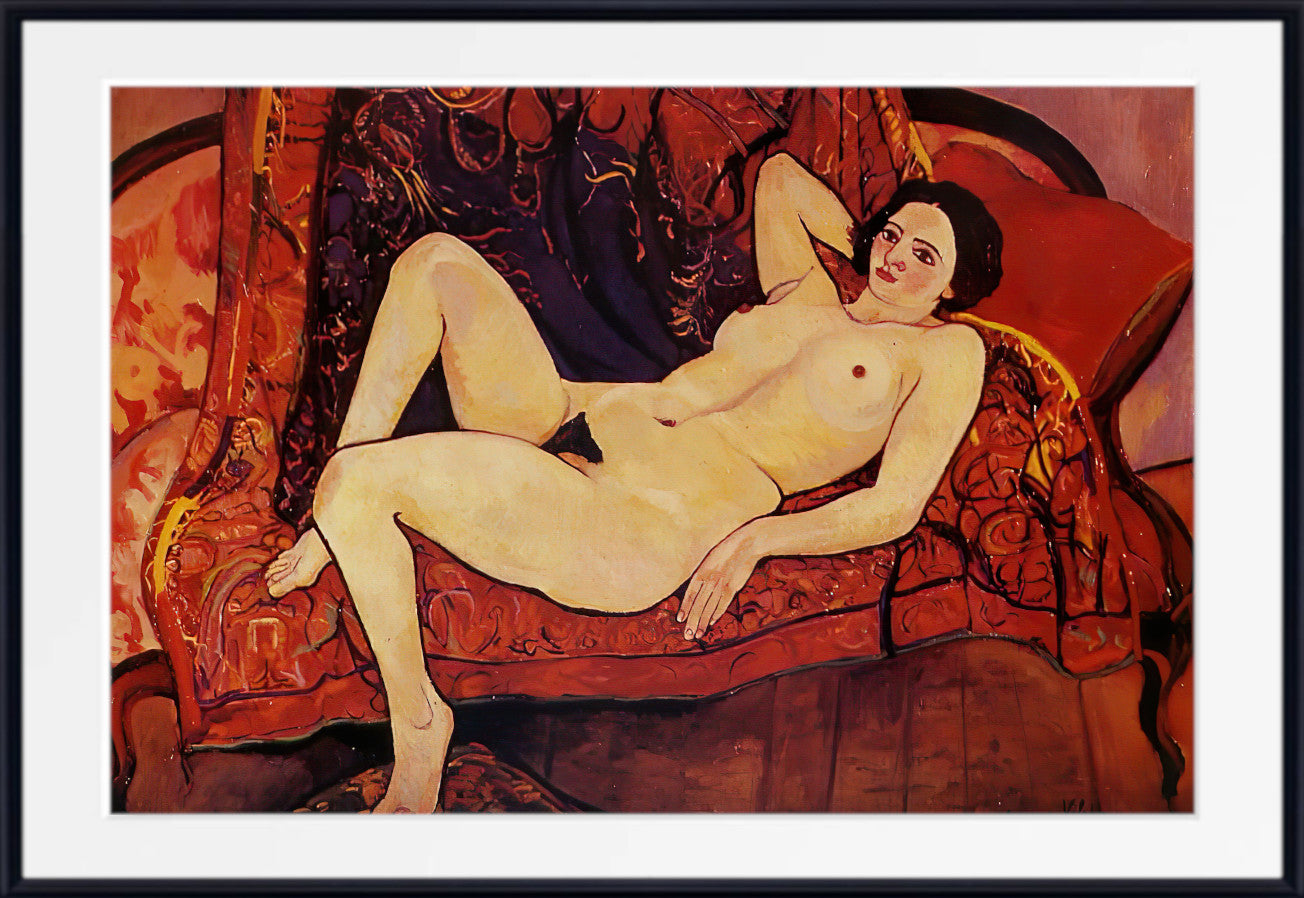

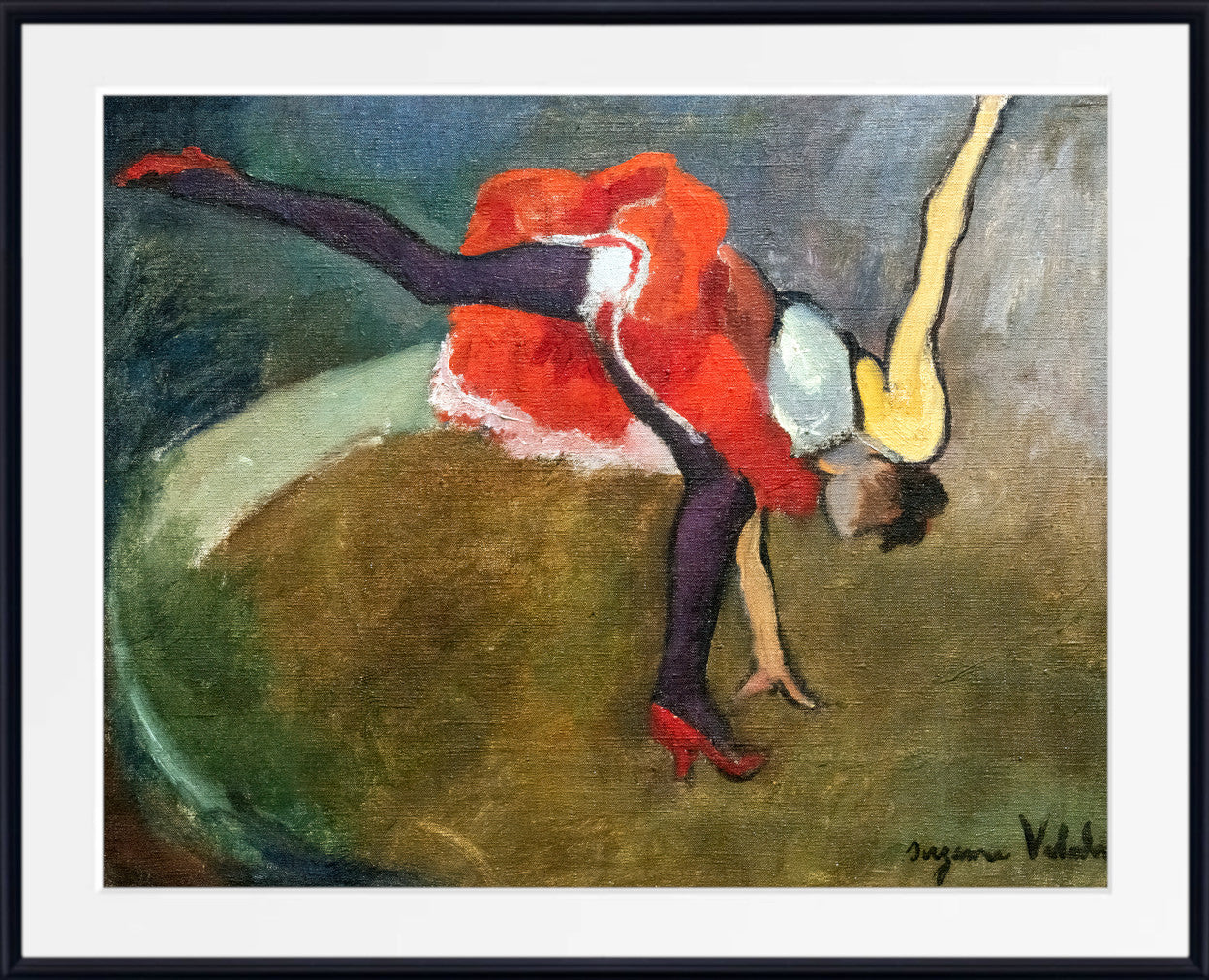

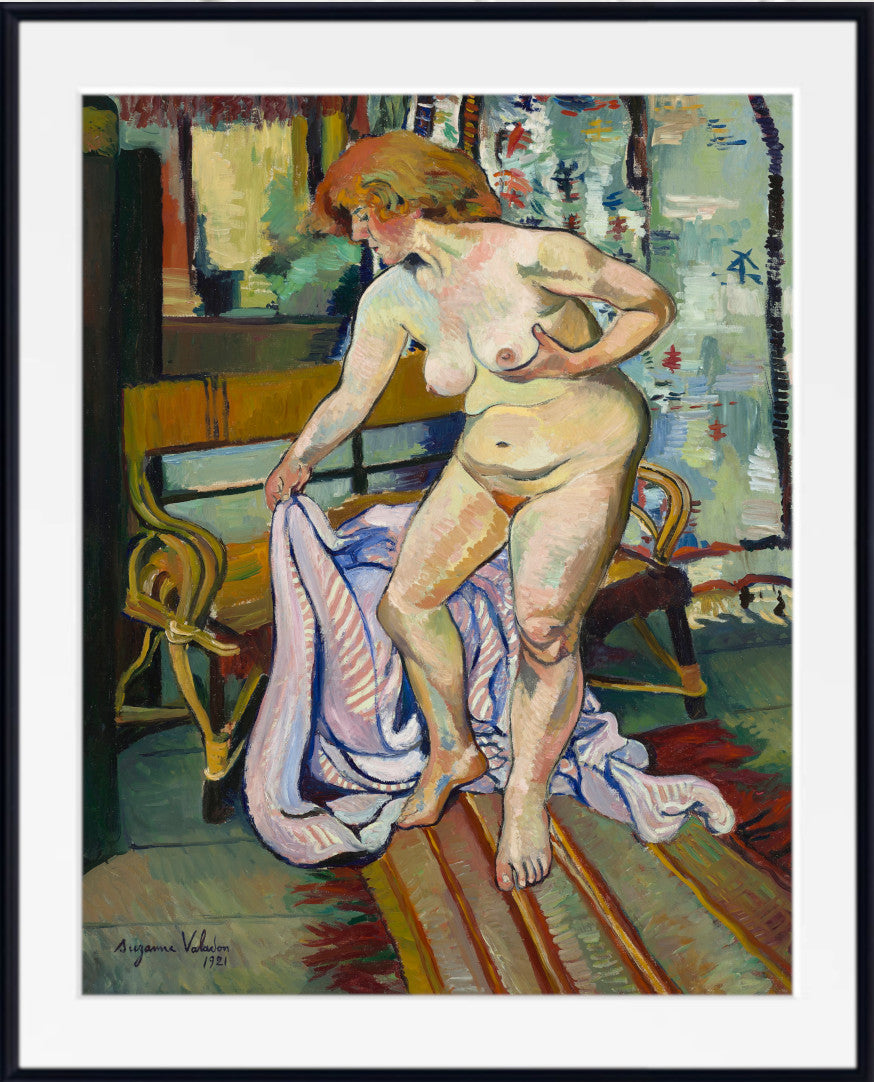

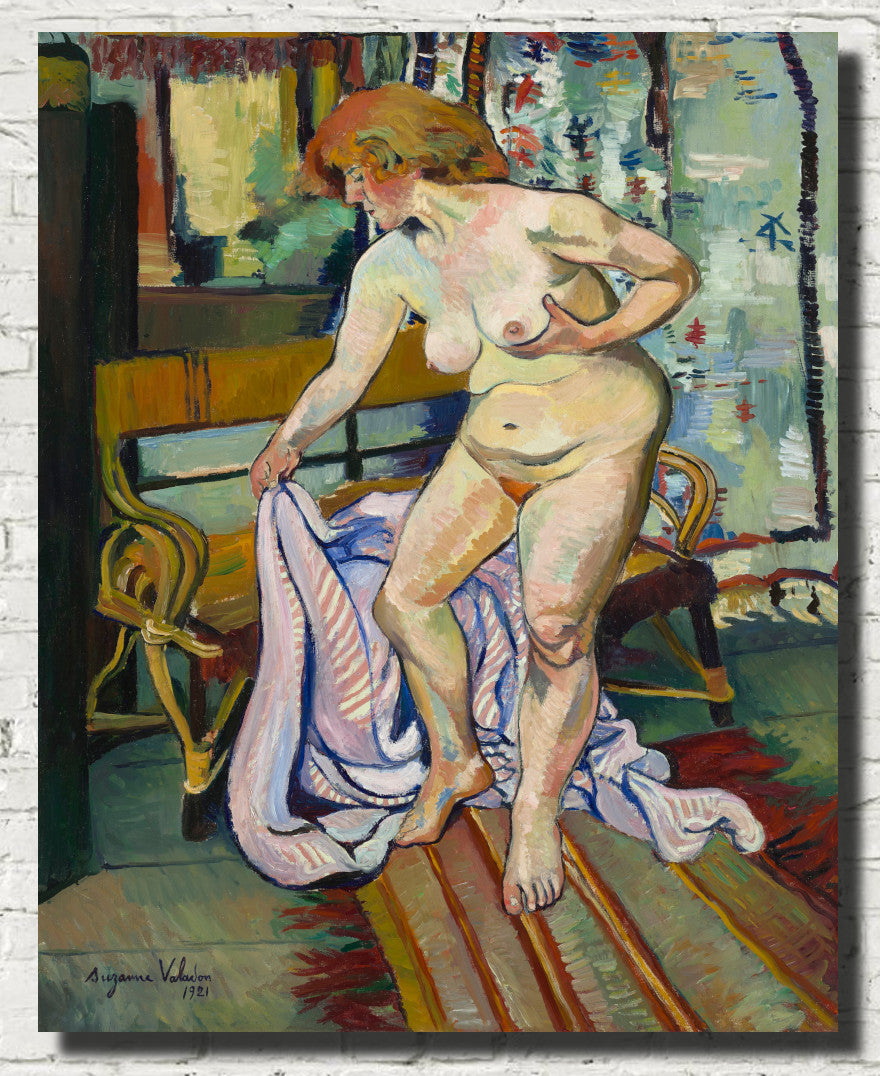

Suzanne Valadon’s The Blue Room (La chambre bleue, 1923) is a bold and subversive work that challenged conventional depictions of women in art. Painted during a pivotal period in her career, this vivid composition offers a striking portrayal of feminine autonomy, modern identity, and post-Impressionist innovation. Today housed in the Centre Pompidou in Paris, The Blue Room continues to resonate with contemporary audiences for its radical subject matter and pioneering vision.

Who Was Suzanne Valadon?

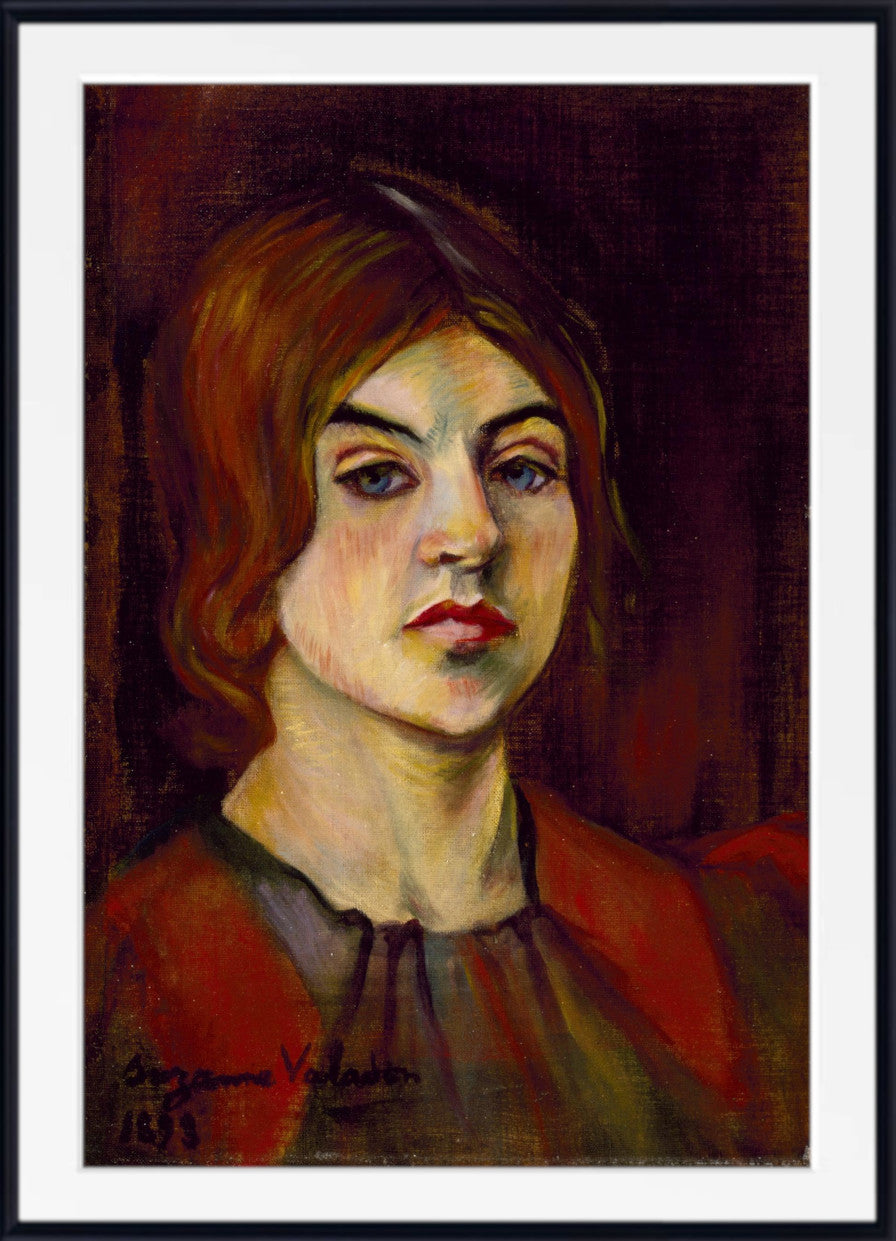

From Artist’s Model to Master Painter

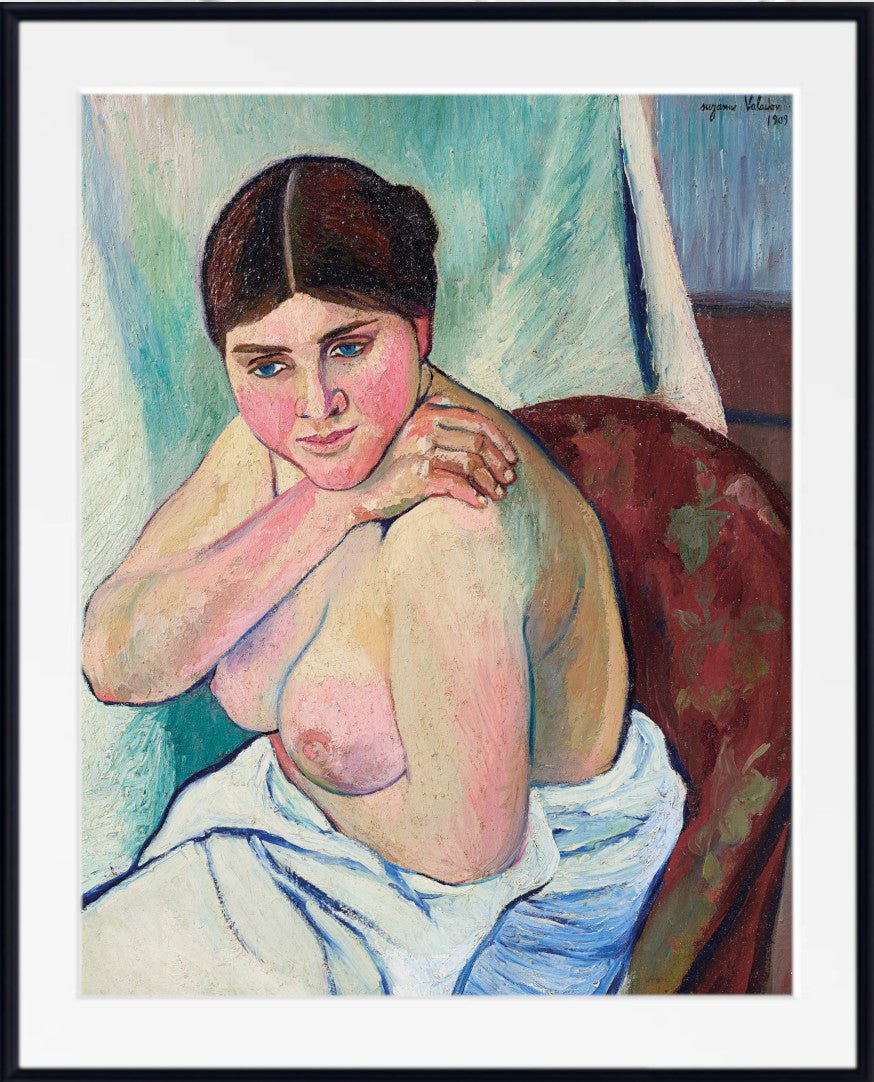

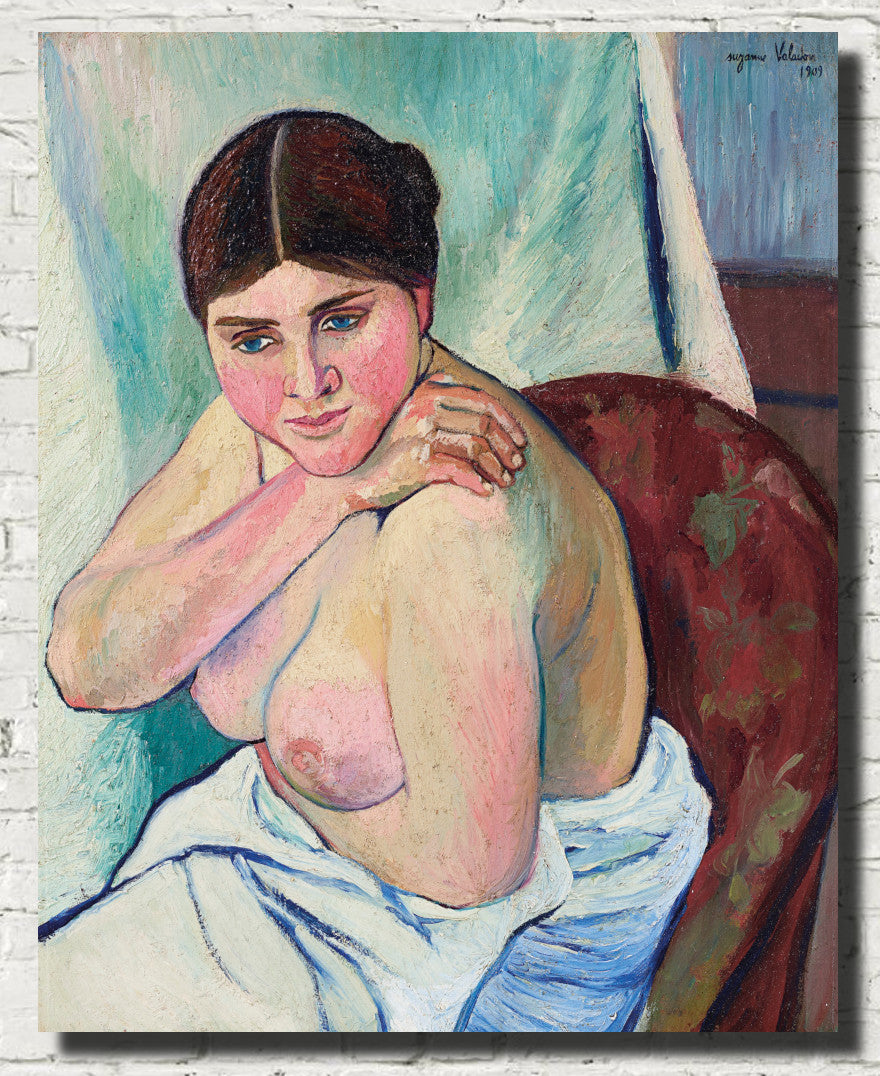

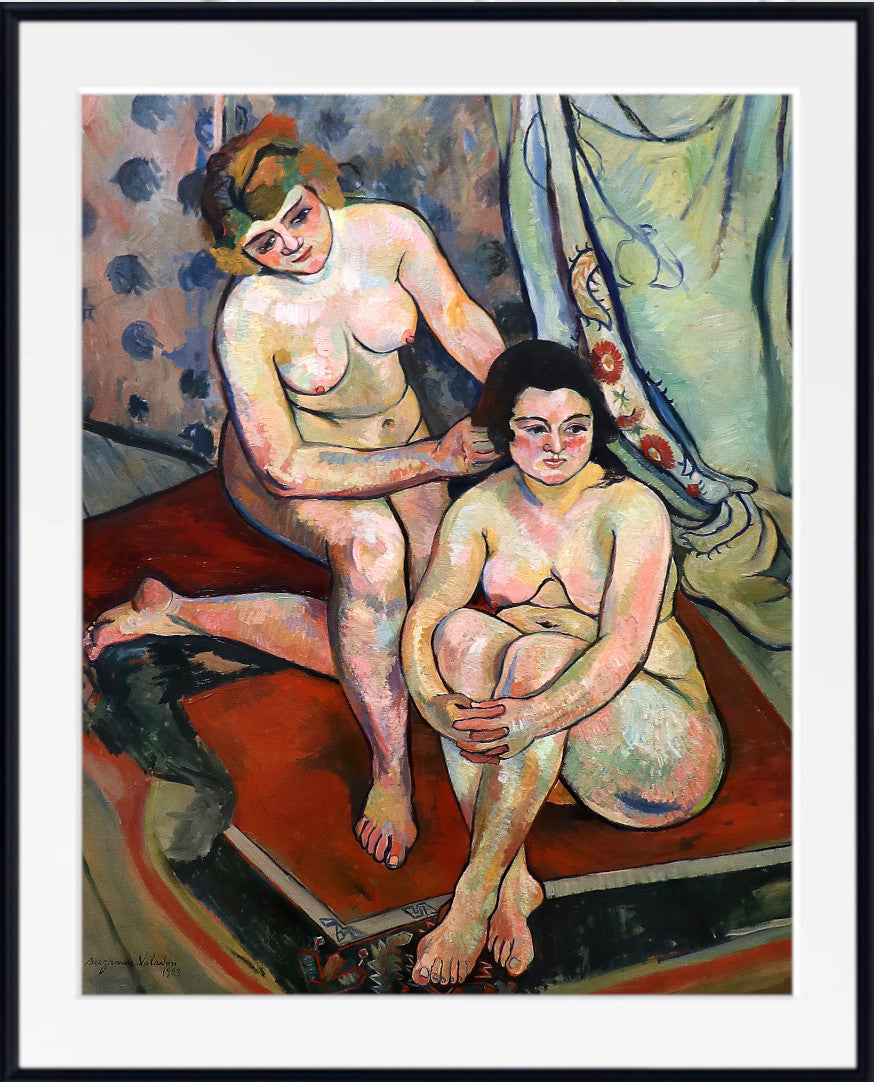

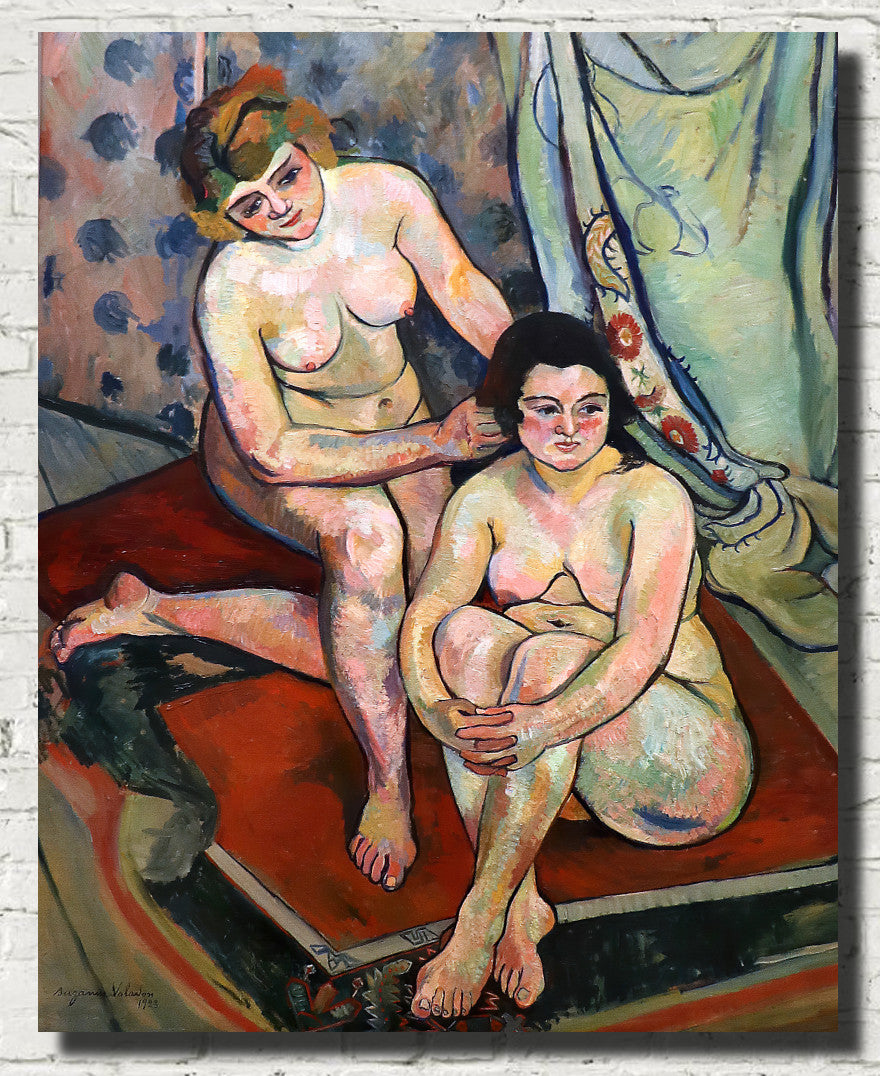

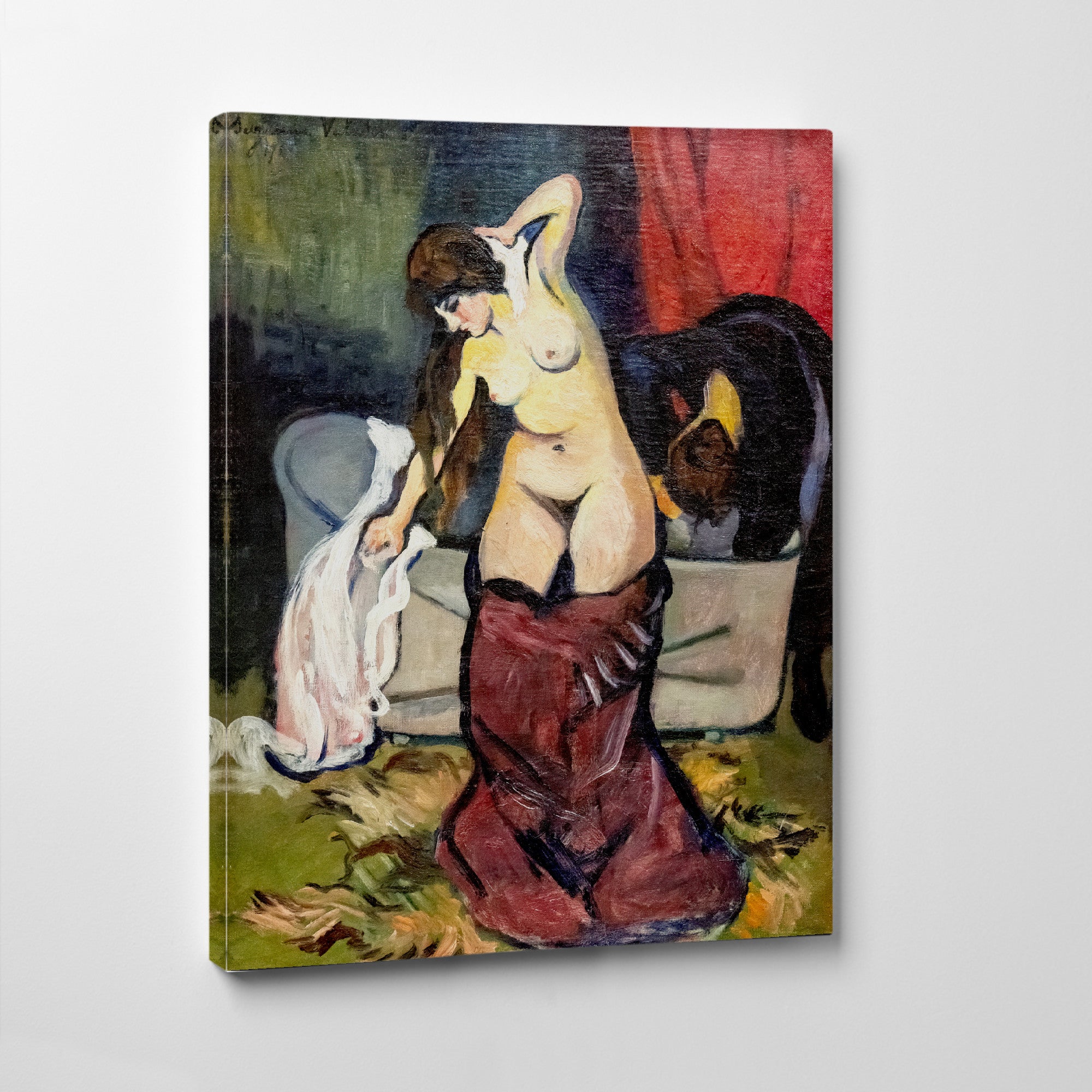

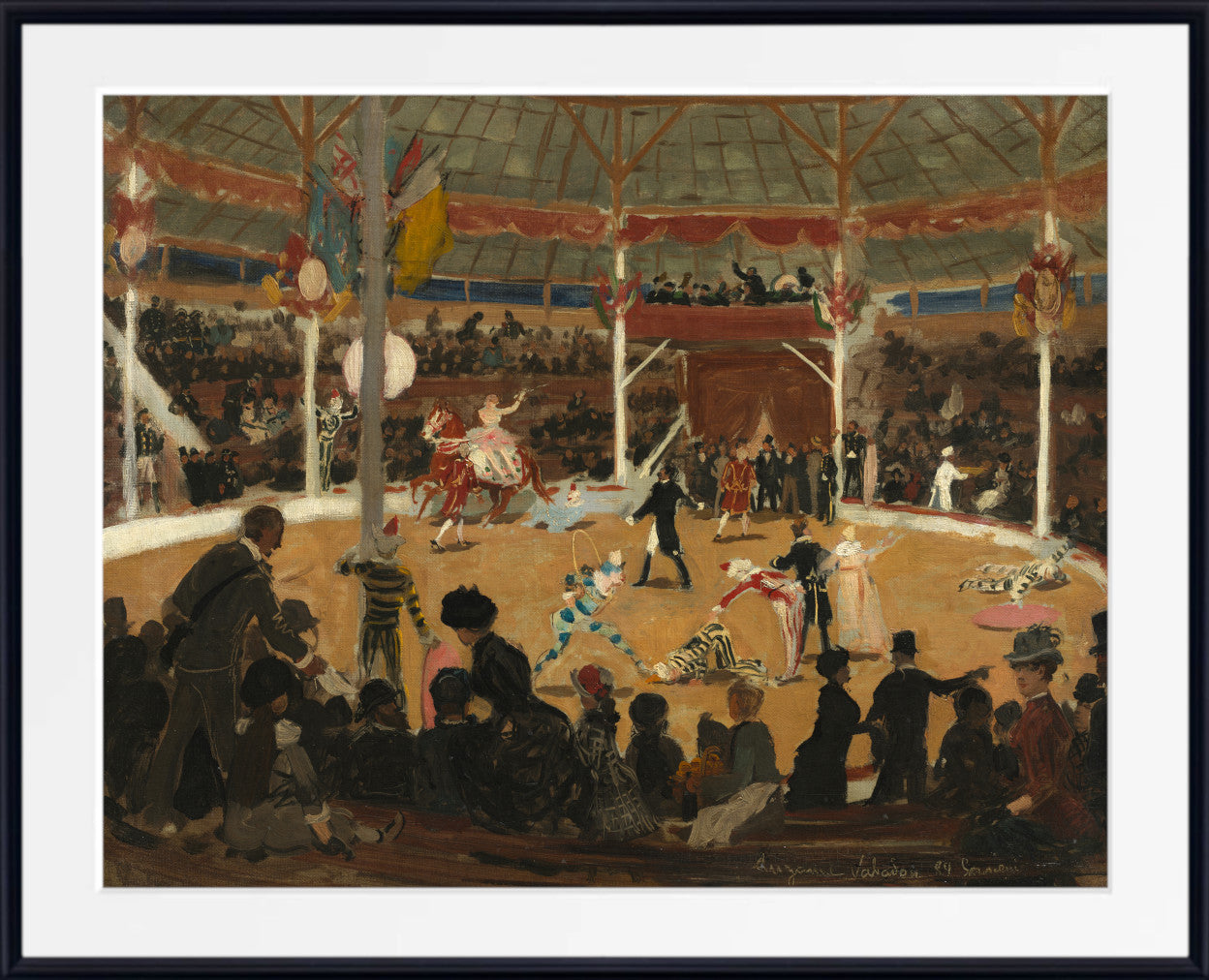

Born in 1865 in Montmartre, Suzanne Valadon began her artistic journey as an artist’s model, posing for some of the most famous names of the late 19th century, including Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Degas. Though she never received formal training, Valadon observed and absorbed techniques from the artists around her. With encouragement from Degas, she turned to painting and drawing, quickly developing her own distinctive style.

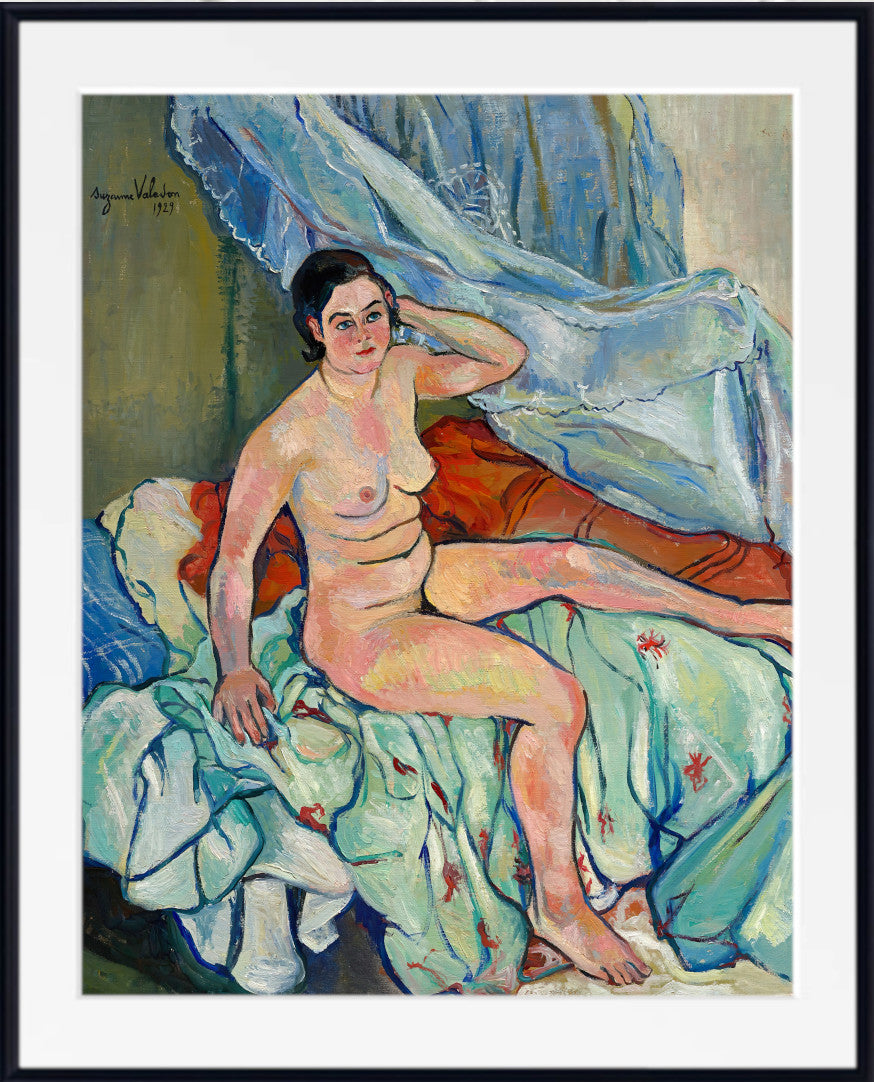

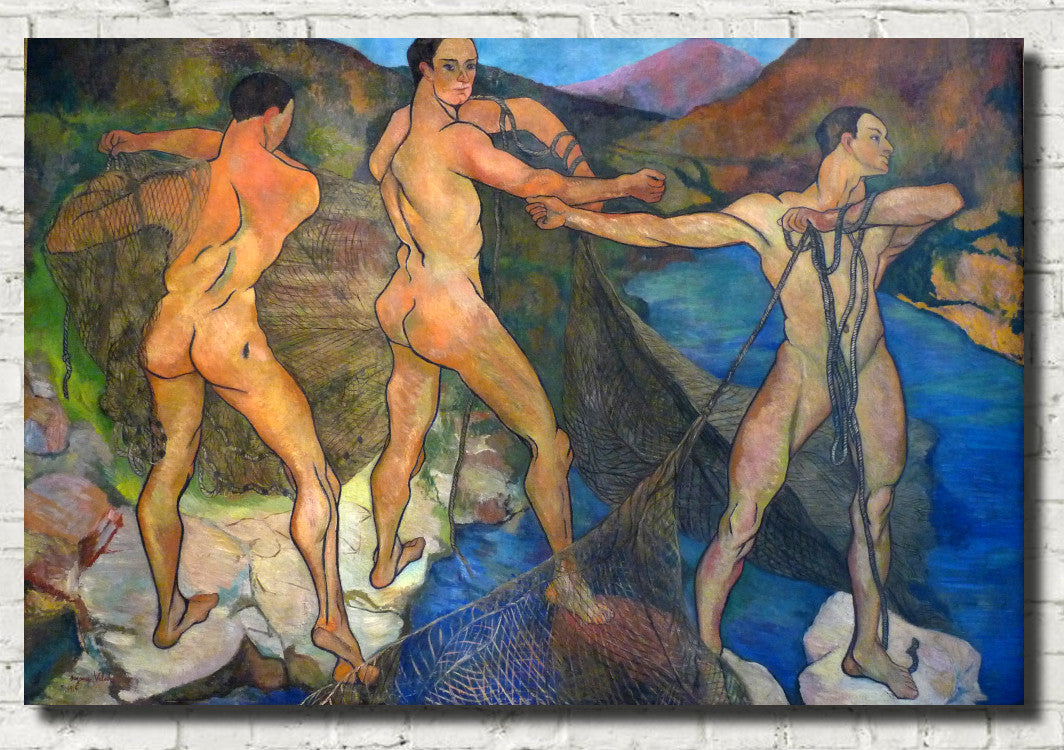

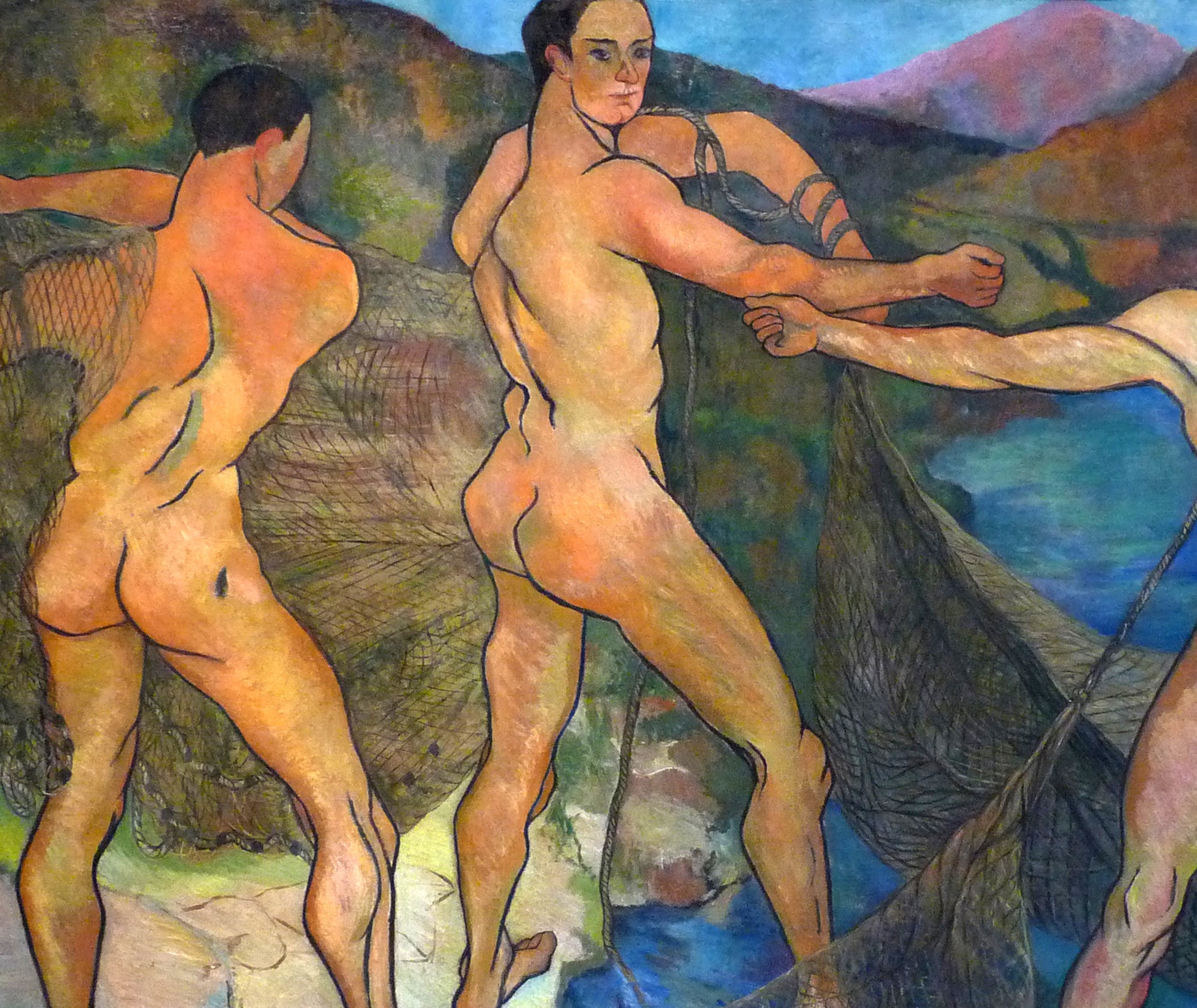

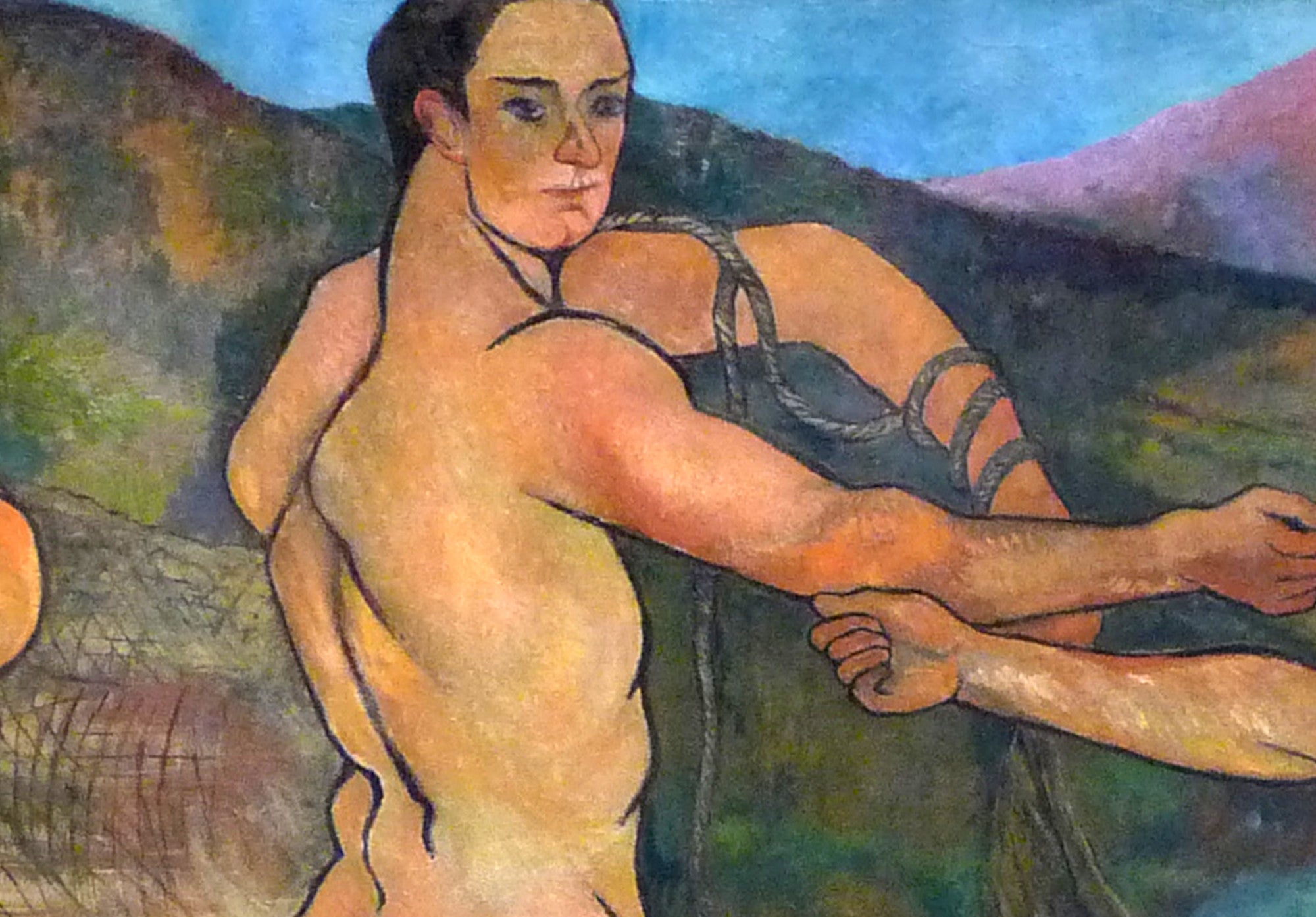

Valadon became the first woman admitted to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1894. Her work—characterised by bold outlines, strong forms, and a fearless commitment to truth—stood apart in a male-dominated art world. Unlike the soft, impressionistic nudes of her contemporaries, her figures were muscular, defiant, and often emotionally intense.

The Blue Room (1923): Overview and Analysis

A Radical Reimagining of the Reclining Female Figure

At the centre of The Blue Room is a reclining woman dressed in floral-patterned trousers and a short-sleeved blouse, her form relaxed as she lies across a daybed with a book in hand and a lit cigarette at her side. She is not a symbol of erotic fantasy but an autonomous individual, fully engaged in her own world.

This scene directly confronts centuries of artistic tradition. From Titian’s Venus of Urbino to Manet’s Olympia, the reclining female nude had long been a staple of Western art—almost always posed for the male gaze. In contrast, Valadon clothes her subject, granting her agency, intellect, and physical presence without objectification.

Symbolism and Subject Identity

While the exact identity of the model remains unknown, she has been interpreted as a representation of the “New Woman” of the 1920s: literate, self-assured, and independent. The cigarette and the book are important modern symbols—markers of leisure, intellect, and rebellion against societal norms that traditionally confined women to domestic roles.

The room itself—cluttered with textiles, vibrant patterns, and rich color—enhances the psychological atmosphere. Unlike the sparse, neutral settings of many classical nudes, this is a lived-in, personal space, full of texture and personality. It is a celebration of female subjectivity rather than a stage for male fantasy.

Artistic Style and Technique

Use of Color and Pattern

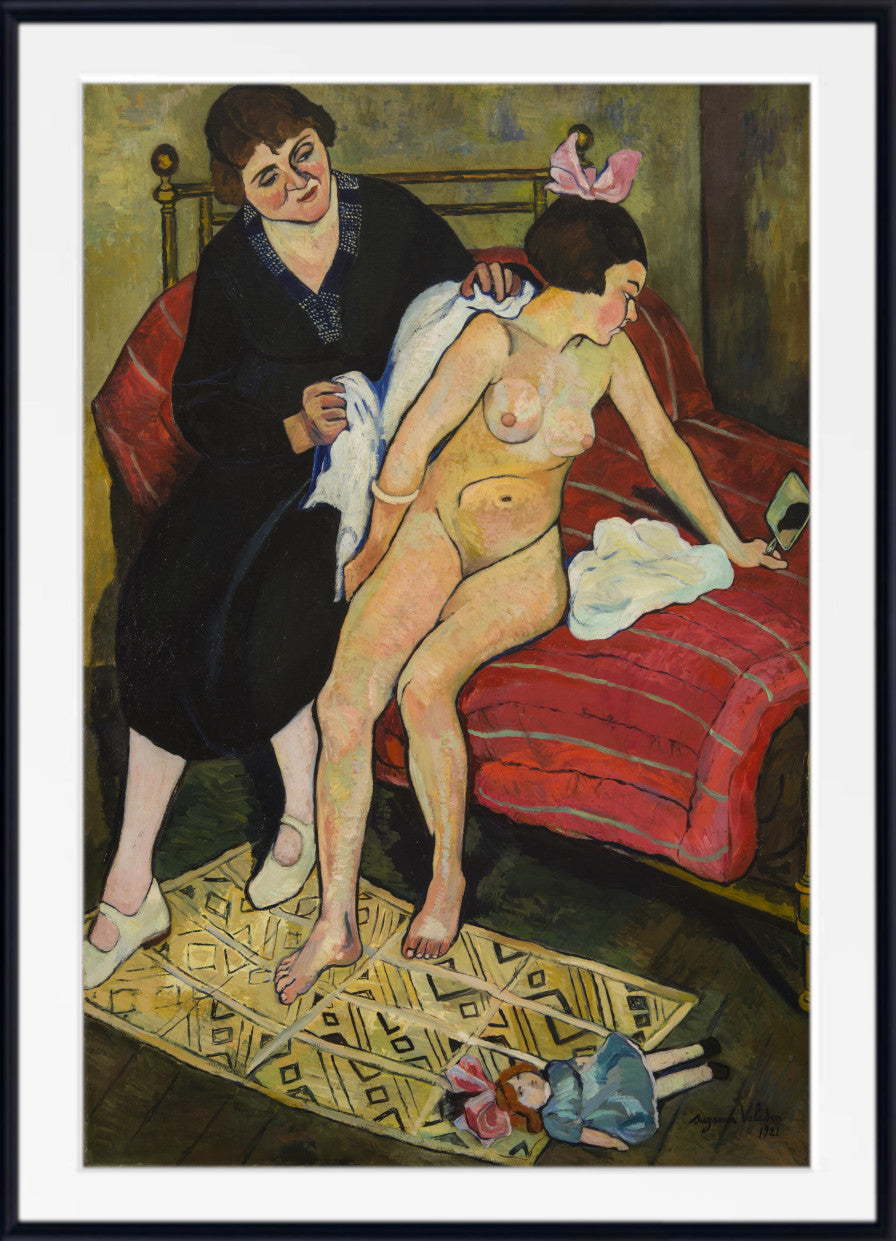

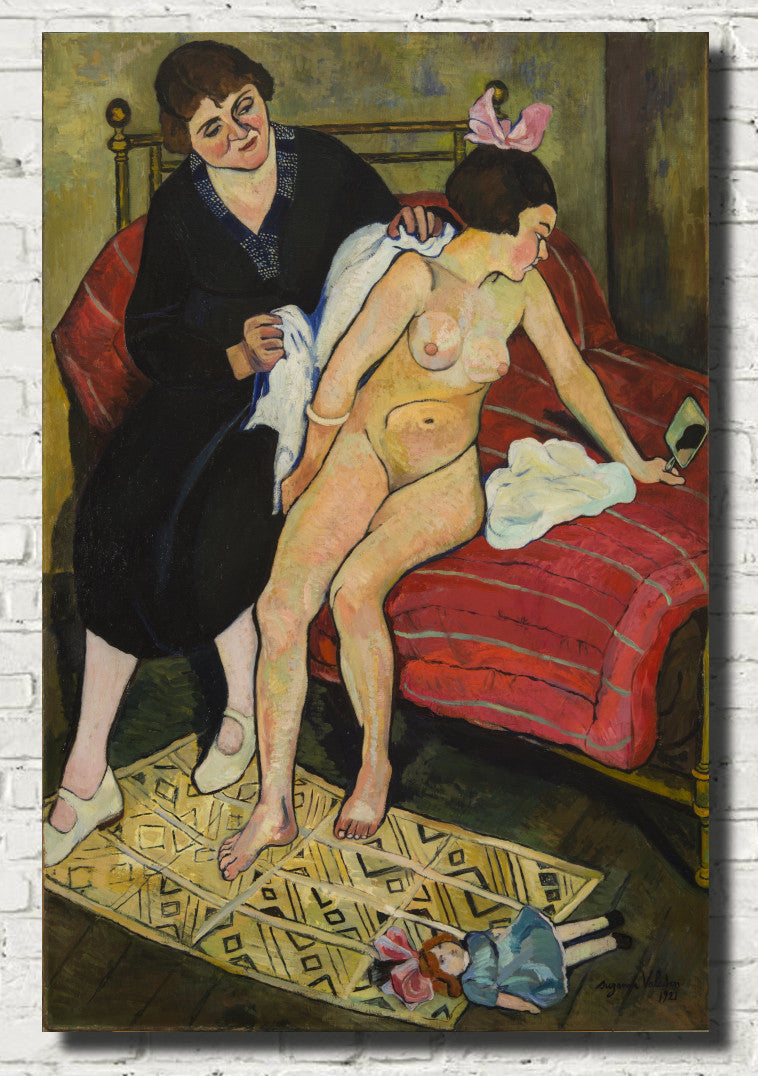

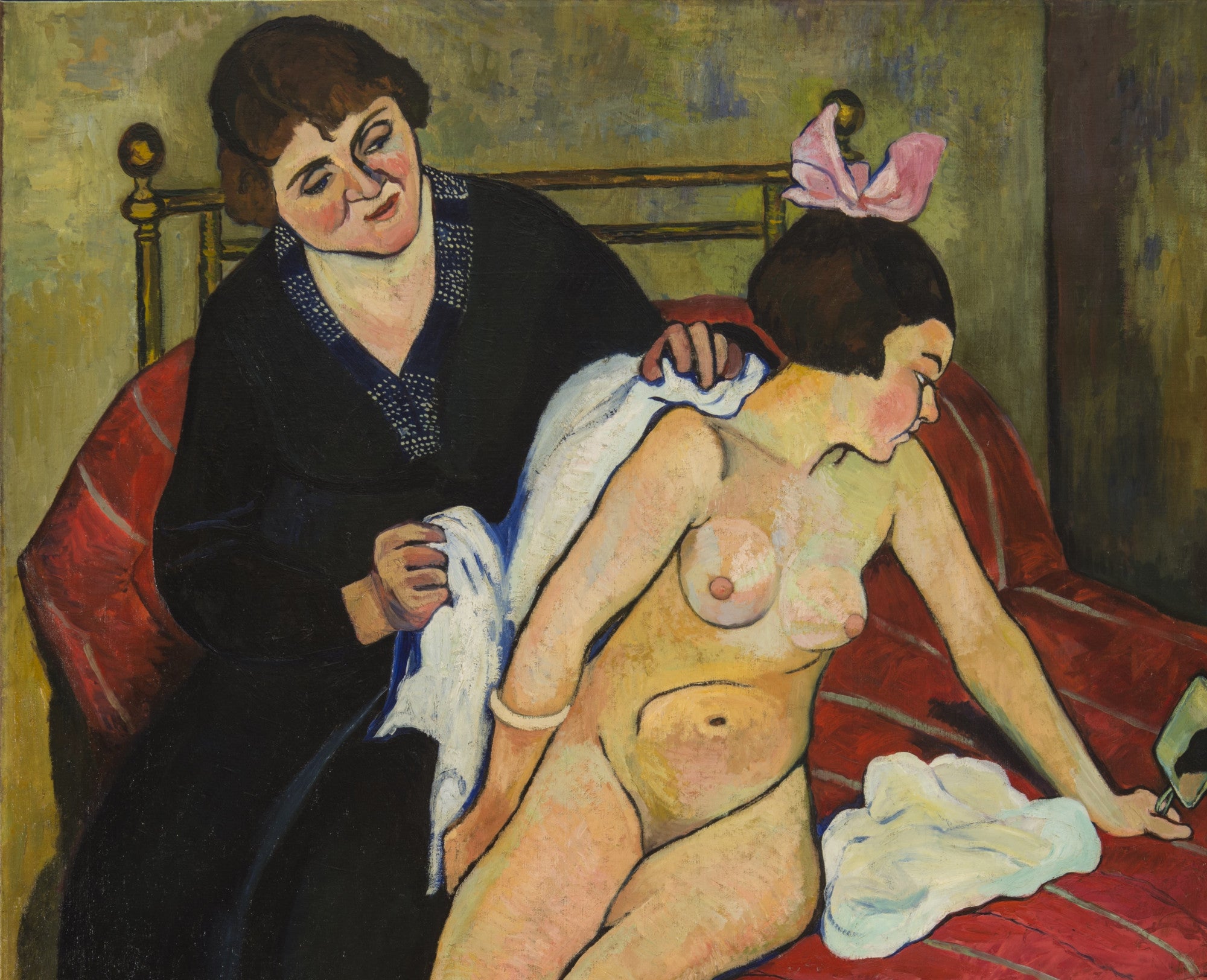

The Blue Room exemplifies Valadon’s post-Impressionist style. The composition is flat and decorative, with bold, saturated hues dominating the canvas. Deep teal walls contrast with the warm yellows and reds of the cushions and bedding. The floral fabrics are almost Fauvist in their intensity, reflecting Valadon’s interest in modern decorative arts and textile design.

Her use of contour lines, often black or darkly toned, gives the painting a graphic quality that anchors the forms amidst the color. This technique, reminiscent of Gauguin and the Nabis, contributes to the painting’s emotional force and compositional clarity.

Compositional Balance

Though seemingly casual, the scene is carefully composed. The reclining figure is diagonally positioned, leading the viewer’s eye from her head to her feet. The surrounding decorative elements echo and balance this line, from the upward tilt of the book to the vertical rhythm of the pillows and floral prints. Valadon’s confidence with spatial organization enhances the intimacy and immediacy of the scene.

Reception and Legacy

Contemporary Significance

When The Blue Room was first exhibited, it stood in sharp contrast to the idealised nudes that dominated the Salon walls. Valadon offered something entirely different: a celebration of feminine independence, bodily confidence, and everyday beauty. Critics and fellow artists alike recognised the power of her work, though her gender often limited the attention she received during her lifetime.

Today, The Blue Room is widely considered a feminist icon. It is frequently cited in discussions of early 20th-century female artists who reclaimed the female body as a site of personal and political meaning. In museum exhibitions, academic scholarship, and feminist art histories, this painting remains a touchstone for discussions on gender, gaze, and agency in visual art.

Influence on Future Generations

Valadon’s work, particularly The Blue Room, paved the way for future generations of female artists who sought to challenge patriarchal visual conventions. From Frida Kahlo to Alice Neel, echoes of Valadon’s insistence on psychological depth, bodily realism, and female empowerment can be found throughout modern and contemporary art.

Where to See The Blue Room Today

The Blue Room is part of the permanent collection at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, France. As one of Suzanne Valadon’s most celebrated works, it is frequently on display and often featured in exhibitions focusing on women artists and modernist innovation. Visitors to the museum can see the painting firsthand and explore its dynamic color palette, powerful form, and revolutionary subject.

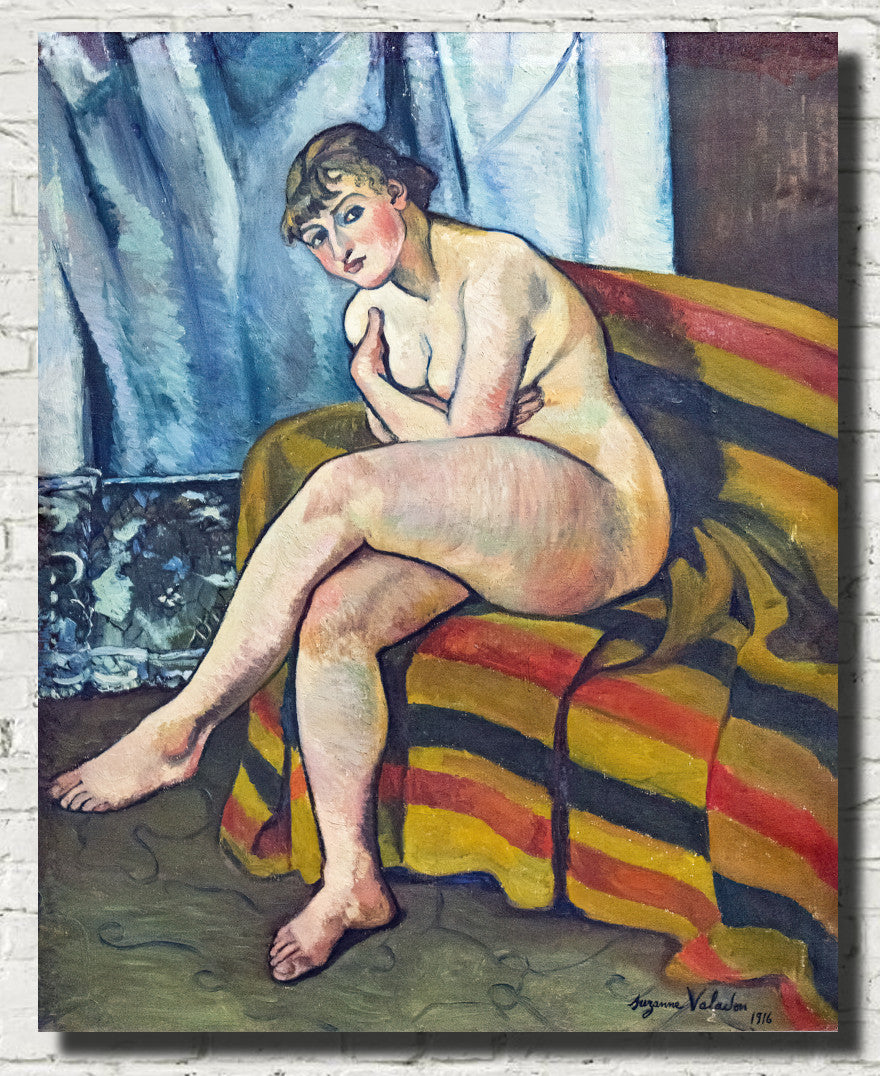

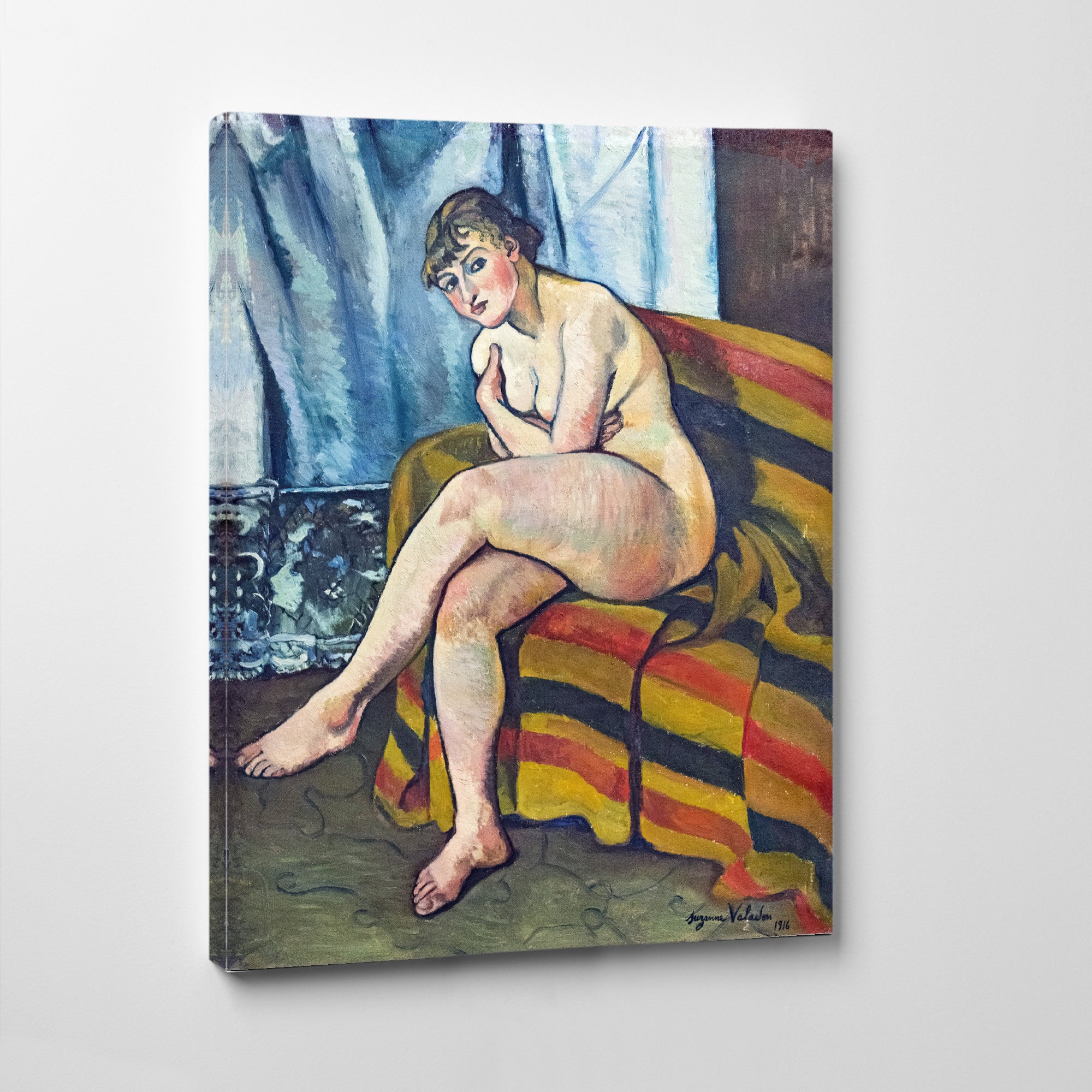

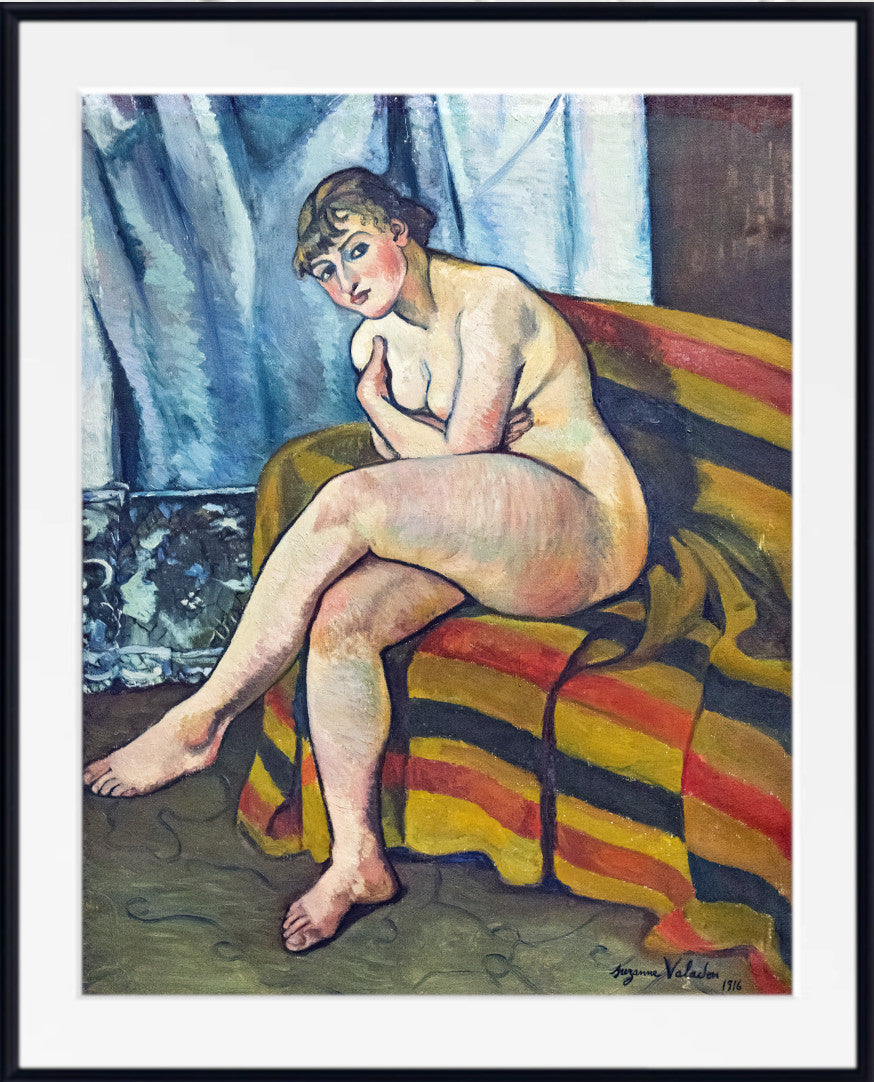

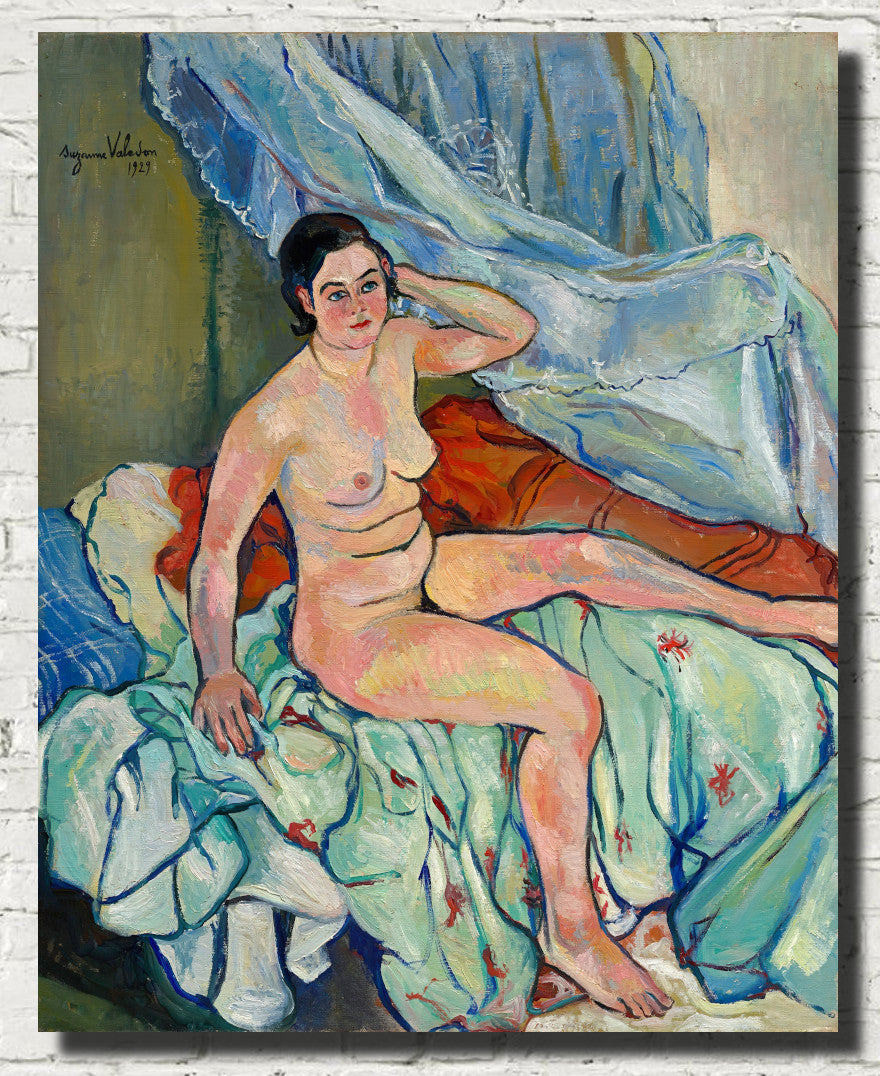

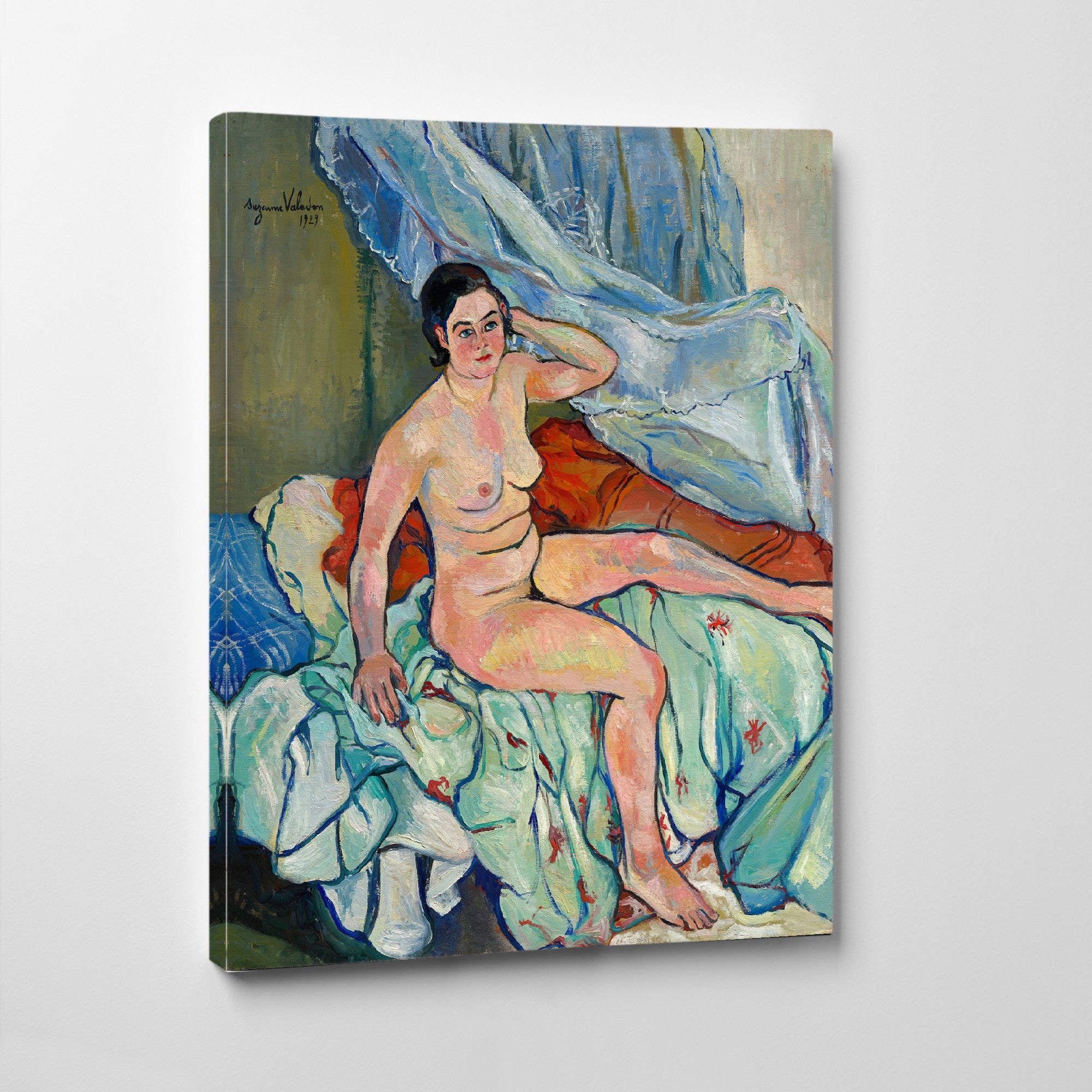

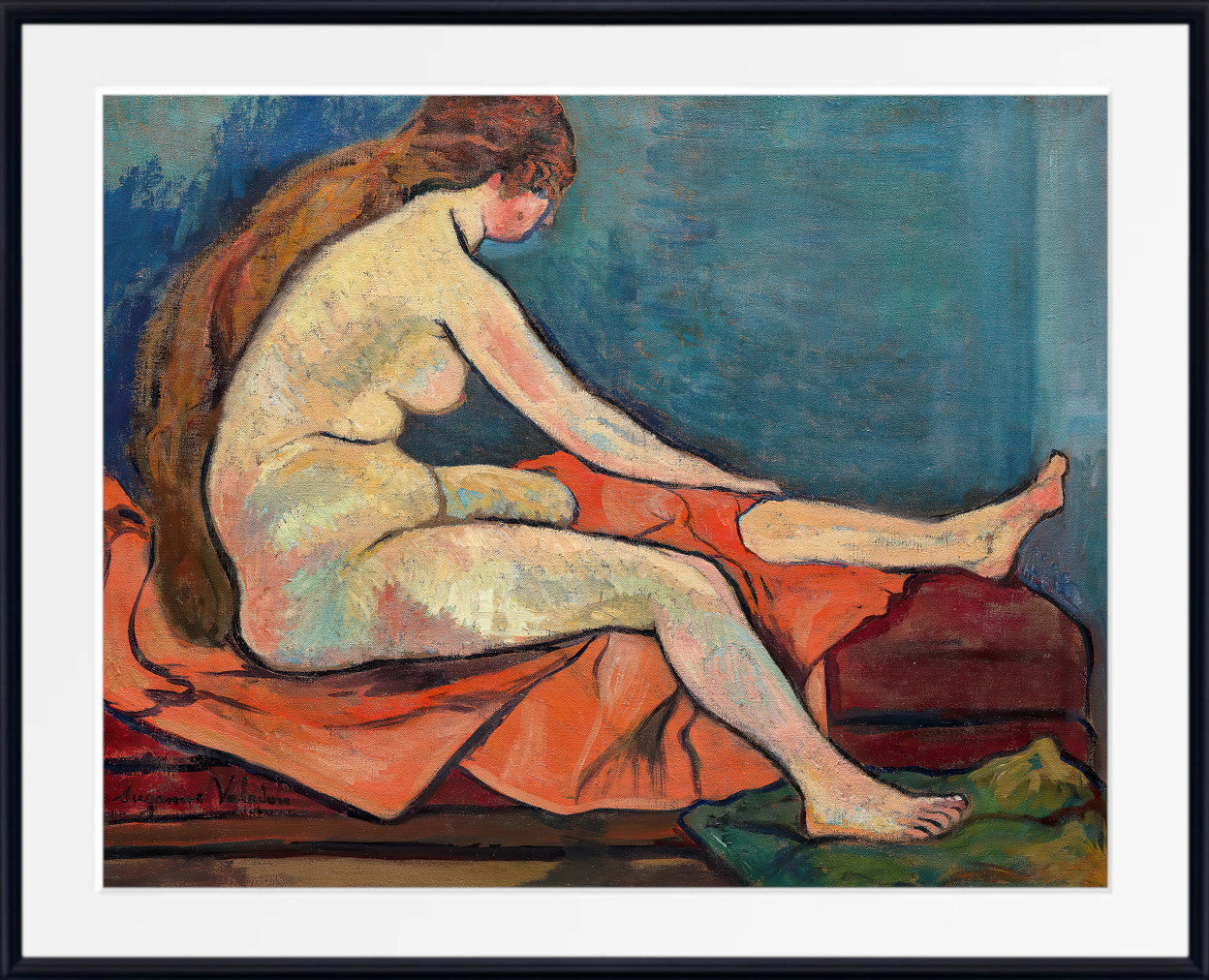

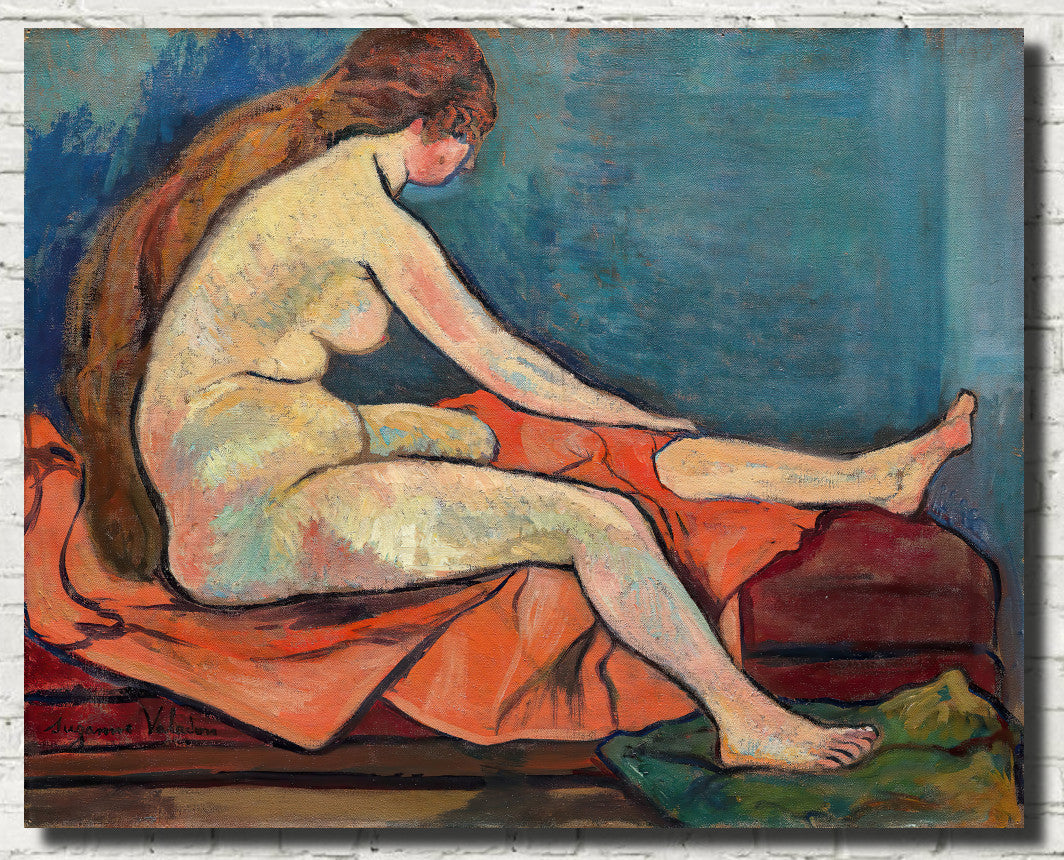

Prints and Canvas Panels

Conclusion

Suzanne Valadon’s The Blue Room (1923) is more than just a portrait of a woman in a domestic setting—it is a manifesto in paint. With bold color, psychological depth, and unwavering commitment to truth, Valadon rejected centuries of artistic convention and gave viewers a new vision of femininity: modern, autonomous, and fully human. Nearly a century after it was painted, The Blue Room continues to captivate and challenge, solidifying Valadon’s rightful place in the canon of modern art.

Summary

Suzanne Valadon’s The Blue Room (1923) is a groundbreaking modernist painting that redefines the female nude through bold color, confident brushwork, and a feminist lens. A celebration of feminine autonomy, it remains one of the most significant and enduring artworks of the 20th century.