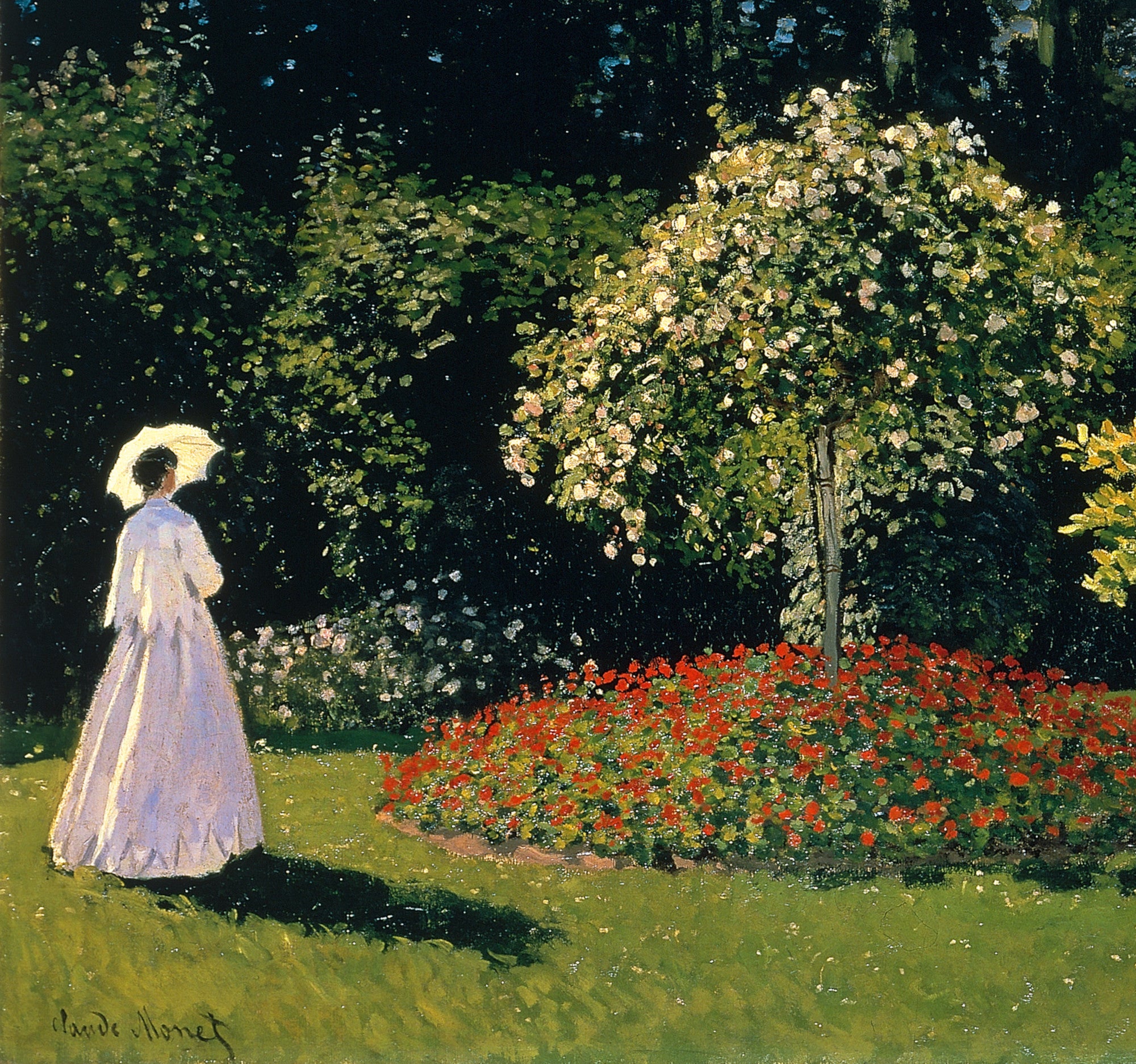

The Impressionism art style was one of the most important and influential developments in Western art in the 19th century. Led by a group of independent artists in Paris, it marked a clear break from traditional artistic concepts of the past.

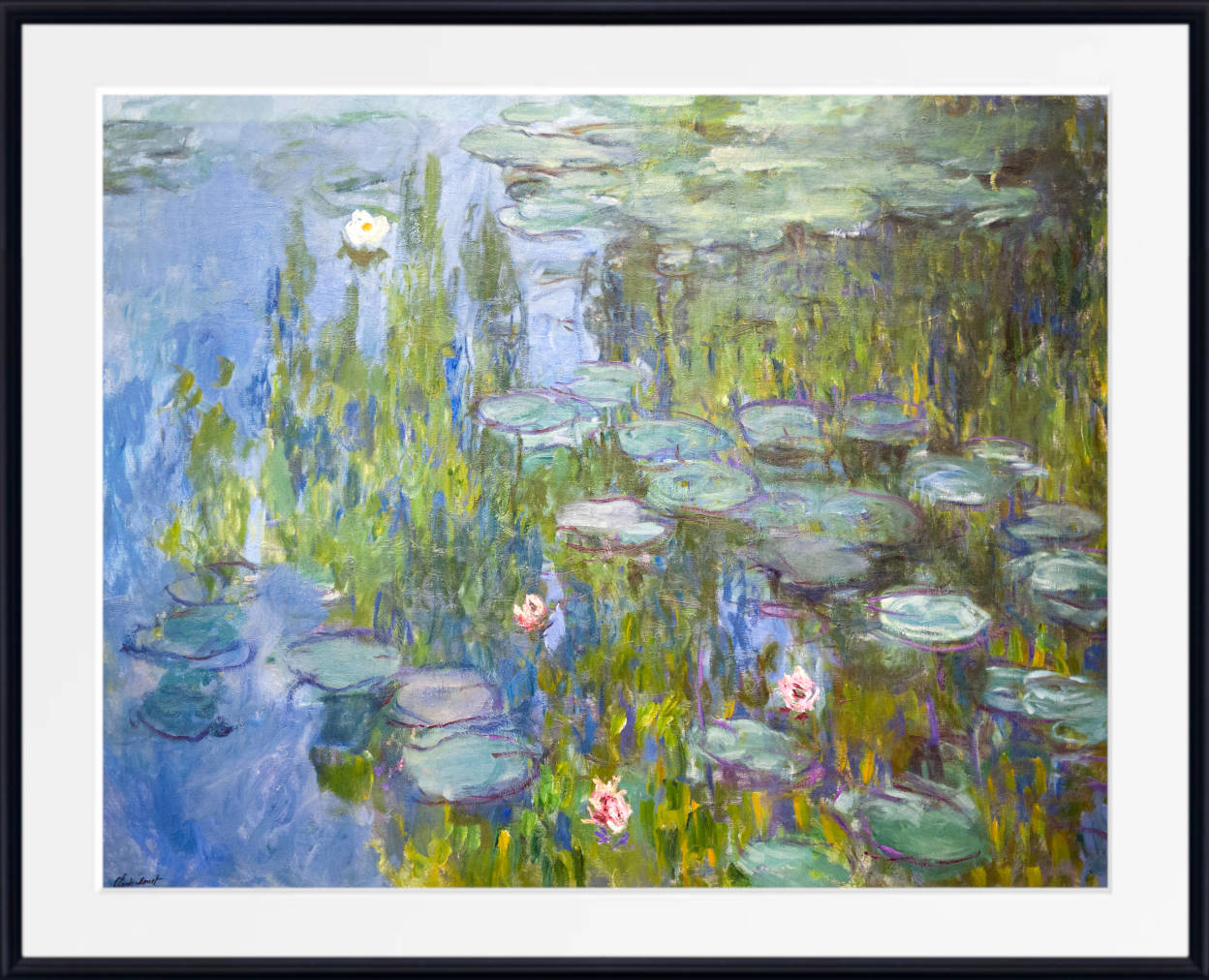

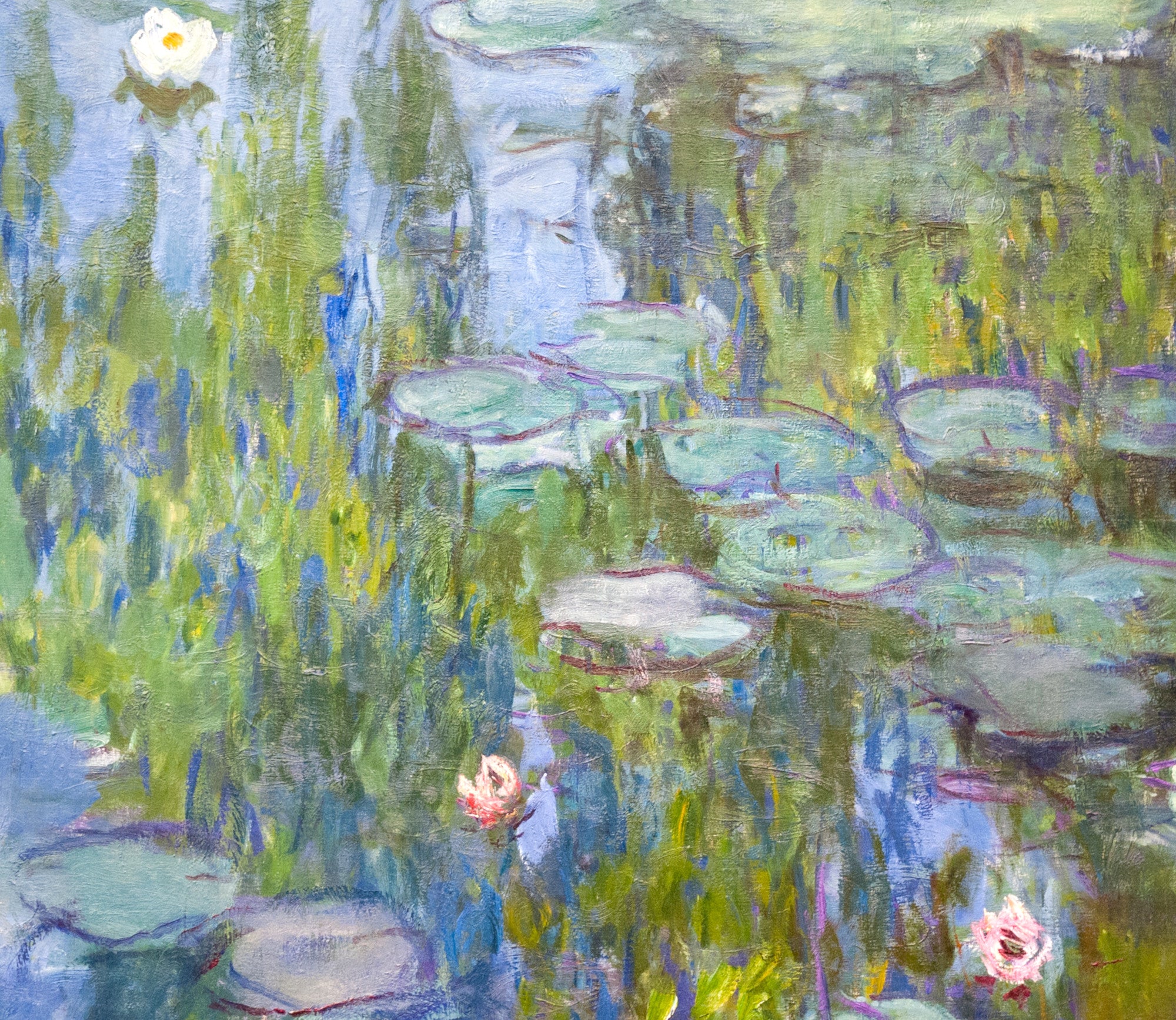

The Impressionists faced harsh opposition from the conventional art community in France. The name of the style derives from the title of a Claude Monet work, Impression, soleil levant (Impression, Sunrise), which provoked the critic Louis Leroy to coin the term in a satirical review published in the Parisian newspaper Le Charivari.

Although it was a revolutionary movement, Impressionism had roots in other styles of painting, such as Realism and Naturalism, that were already challenging conventional notions of artistic beauty and the artist’s relationship with the state. The Realism movement, championed by Gustave Courbet, was the first to confront the official Parisian art establishment, in the middle of the 19th century. Courbet was an anarchist who thought that the art of his time closed its eyes on realities of life. The French were ruled by an oppressive regime and much of the public was in the throes of poverty. Instead of depicting such scenes, the artists of the time concentrated on idealized nudes, classical and mythological narratives, and glorifying depictions of nature. As an act of protest, Courbet financed an exhibition of his work directly opposite the Universal Exposition in Paris of 1855, a bold act that inspired future artists who sought to challenge the status quo. At the same time, the emergence of Naturalism - a movement closely associated with Realism - showed how art could take the natural world for its subject-matter without cloaking it in the contexts of historical or mythological heroism. Since the 1820s, artists such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Jean-François Millet had been travelling to the Barbizon Forest south of Paris to create sketches en plein air of the trees, countryside, and rural laboring classes. The emergence of the Barbizon School signified the start of a global trend in painting towards depicting the natural world in all of its unadorned glory, and celebrating the lives of rural workers. While Naturalism diverges from Impressionism in its frequent emphasis on hyperreal detail - embodied by much of the work of Jules Bastien-Lepage - the Impressionists' celebration of the natural world for its own sake, and use of plein air technique, owes much to the earlier Naturalist ethos.

The Garden of the Tuileries on a Winter Afternoon, Camille Pissarro (1899)

Arrival of the Normandy Train, Gare Saint-Lazare, Claude Monet (1877)

Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, Édouard Manet (1863),

The Salon des Refusés

In 1863, at the official yearly art salon, the all-important event of the French art world, a large number of artists were not allowed to participate, leading to public outcry. The same year, the Salon des Refusés ("Salon of the Refused") was formed in response, to allow the exhibition of works by artists who had previously been refused entrance to the official salon. The exhibited artists included Paul Cézanne, Camille Pissarro, James Whistler, and Édouard Manet. Although it was sanctioned by Emperor Napoleon III to placate the artists involved, the 1863 exhibition was highly controversial with the public, due largely to the unconventional themes and styles of works such as Manet's Le déjeuner sur l'herbe (1863), which featured clothed men and naked women enjoying an afternoon picnic (these women were not classical nudes, but modern women - possibly prostitutes - in a state of undress whose connotations were far more explicitly sexual).

The Card Players, Paul Cezanne (1890-92)

Édouard Manet - Revolution in Painting

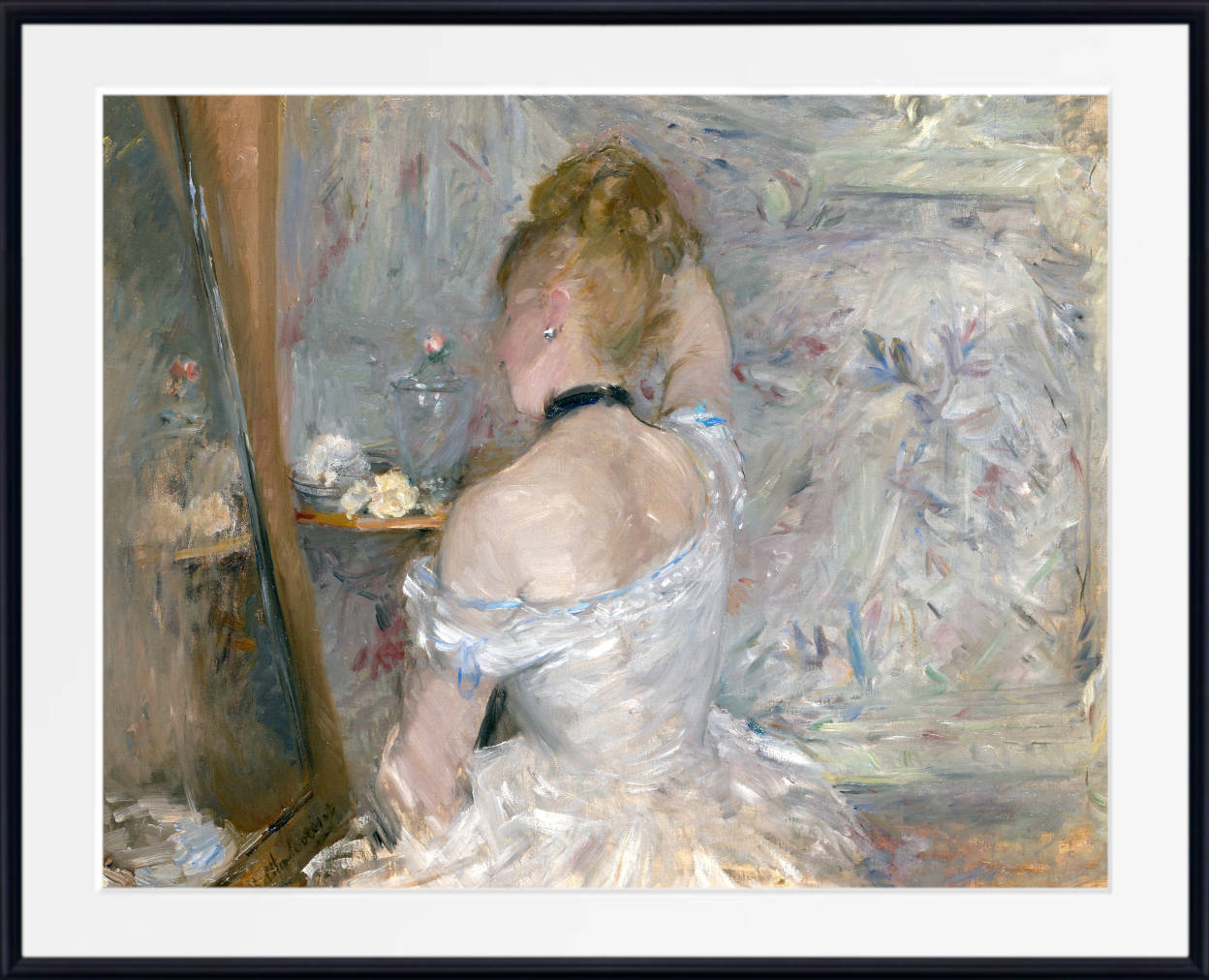

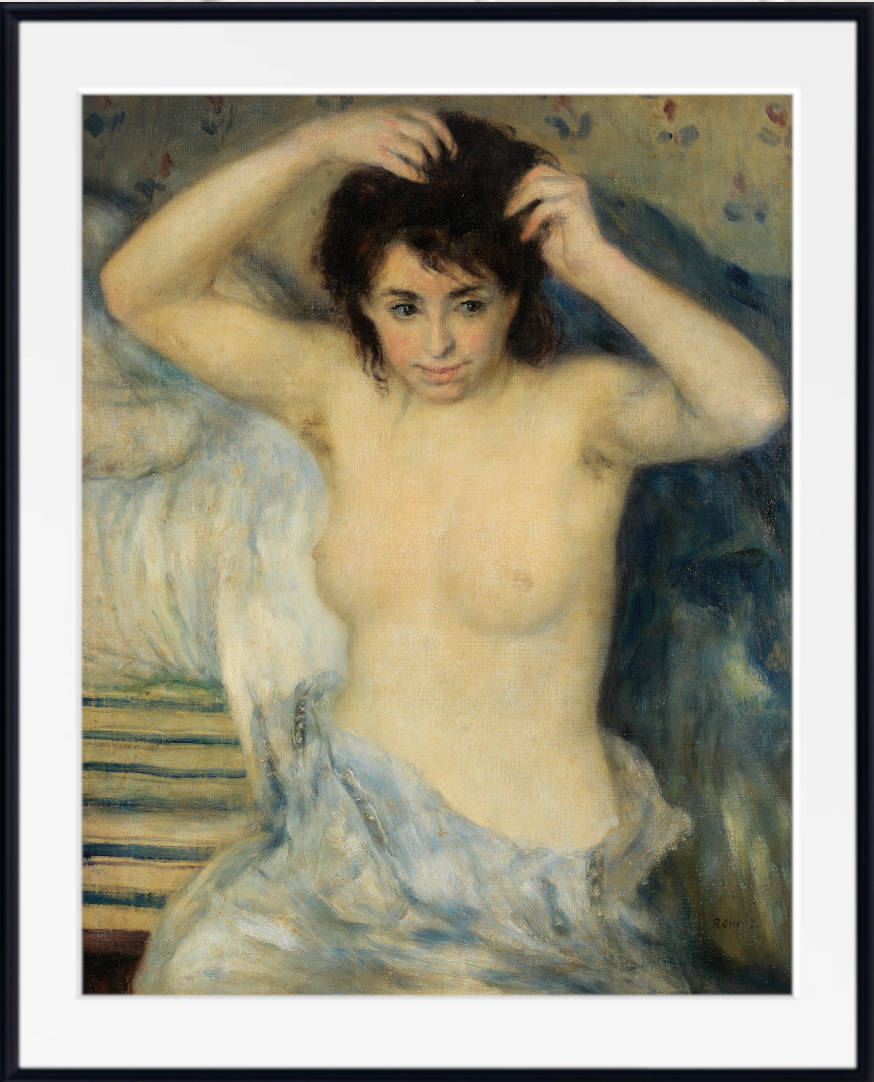

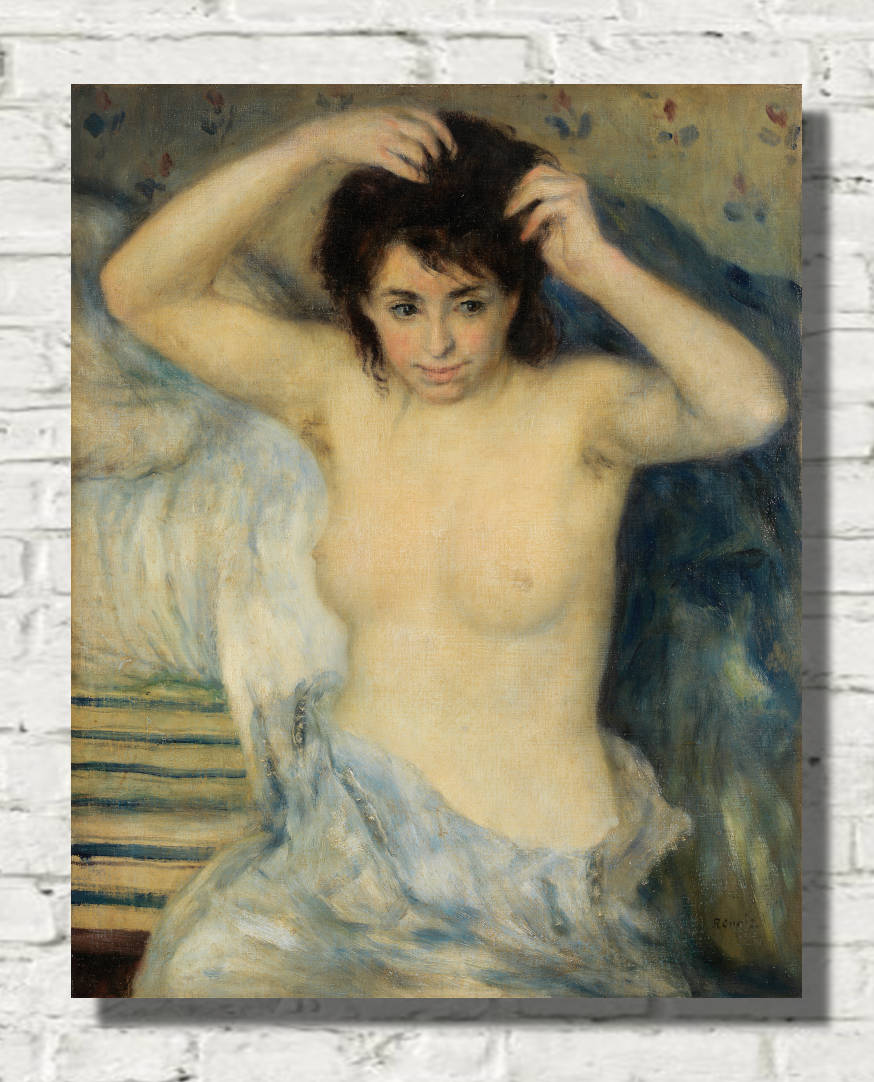

Édouard Manet was among the first and most important innovators to emerge in the public exhibition scene in Paris. Although he grew up in admiration of the Old Masters, he began to incorporate an innovative, looser painting style and brighter palette in the early 1860s. He also started to focus on images of everyday life, such as scenes in cafés, boudoirs, and on streets. His anti-academic style and quintessentially modern subject-matter soon attracted the attention of artists on the fringes and influenced a new type of painting that would diverge from the standards of the time. Works such as Olympia (1863), which, like Le déjeuner sur l'herbe, depicts a modern female nude assertively confronting the viewer, gave the emerging Impressionist group the impetus to depict subjects not previously considered art worthy.

Olympia, Édouard Manet (1863)

The Cafe Artists

Amongst the most popular venues for the painters of the emerging Impressionist movement to meet and talk were Parisian cafés. In particular, Café Guerbois in Montmartre was frequented by Manet from 1866 onwards. Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, and Camille Pissarro all visited the cafe, while Caillebotte and Bazille had studios nearby, and would often join the gatherings. Other personalities were attracted to this group, including writers, critics, and photographers. Part of the interest of the group lay in a dynamic variety of personalities, economic circumstances, and political views. Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro had merchant family or working-class backgrounds, while Berthe Morisot, Gustave Caillebotte, and Degas were from upper-class roots. Mary Cassatt was American (and a woman) and Alfred Sisley was Anglo-French. This diversity of personalities may be the reason so much creativity arose from the group's collective activities.

Bal du moulin de la Galette,Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1876)

The First Impressionist Exhibitions

Though not yet united by any particular style, the group shared a general sense of antipathy toward overbearing academic standards of fine art, and decided to join a commercial cooperative, known as the Anonymous Society of Artists, Painters, Sculptors, Engravers, Etcetera. In general, the painters had very limited financial success, and few of their works were accepted for the salon exhibitions in Paris, so the company was important in establishing their financial solvency and creative independence. In 1874, they held the first of a series of exhibitions in the studio of photographer Felix Nadar. It was not until the third exhibition in 1877 that they began to call themselves The Impressionists. While their first exhibition received limited public attention, and most of the eight exhibitions they held actually cost money rather than earning money for the group, their later shows attracted vast audiences, with attendances running well into the thousands. Despite this attention, most members of the group sold very few works, and some of them remained incredibly poor throughout this period.

In the Dining Room, Berthe Morisot

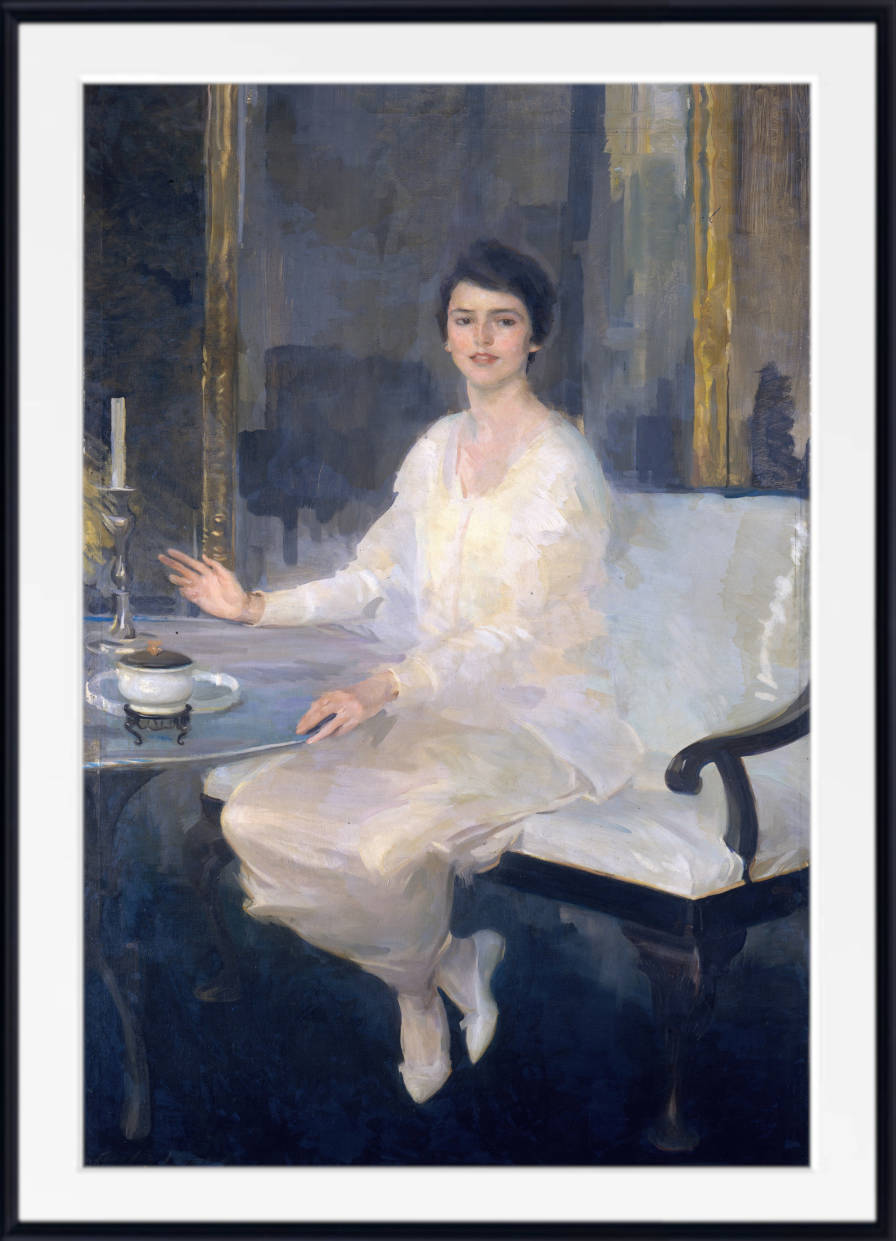

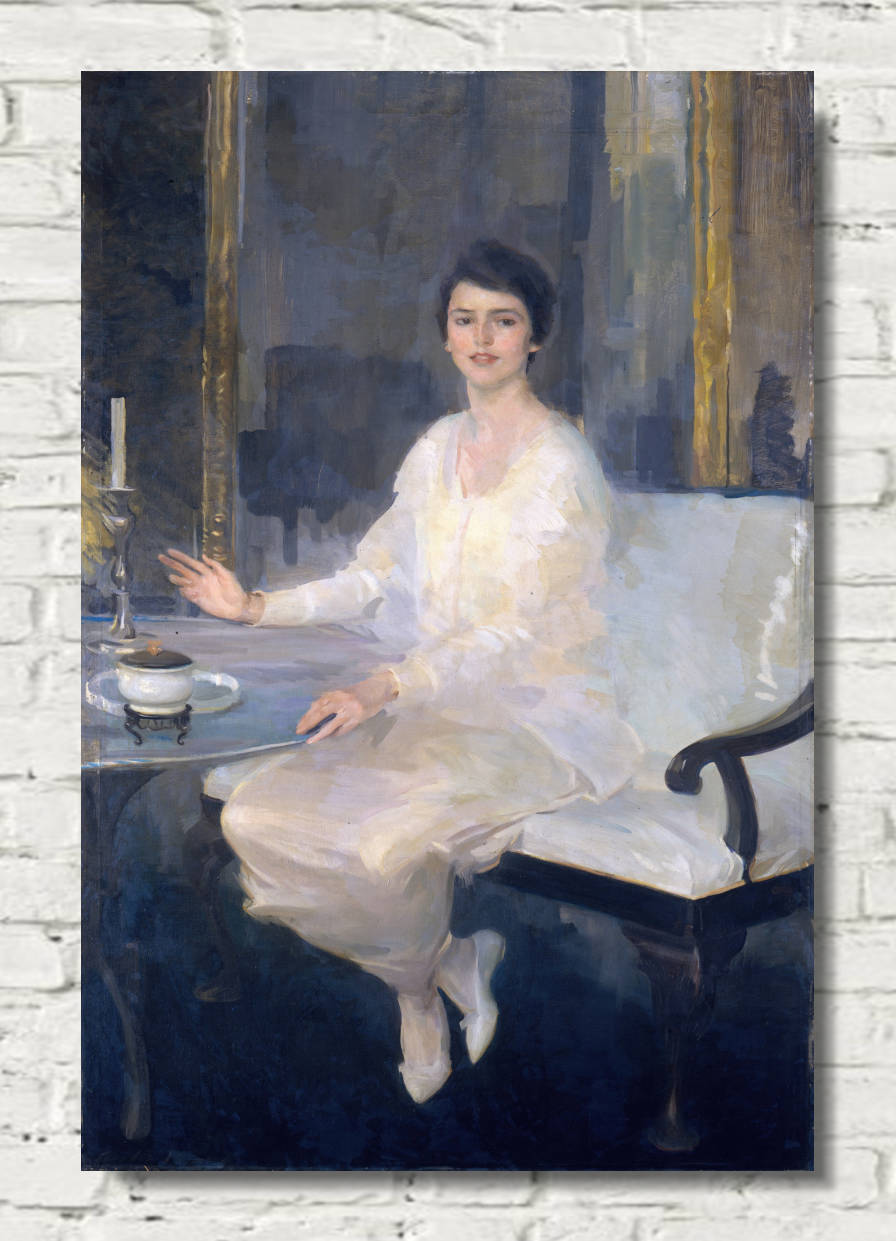

First Women Impressionists

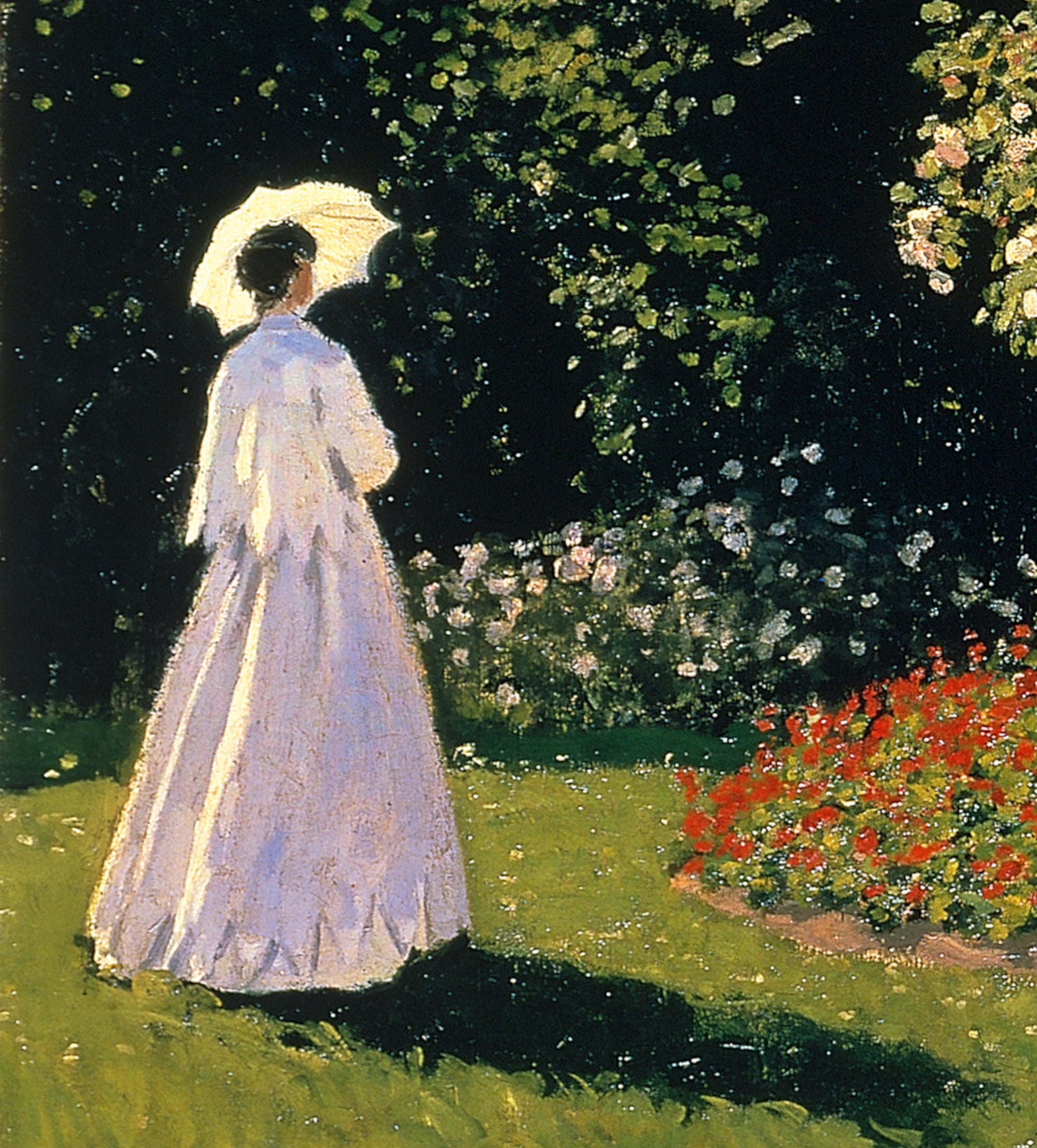

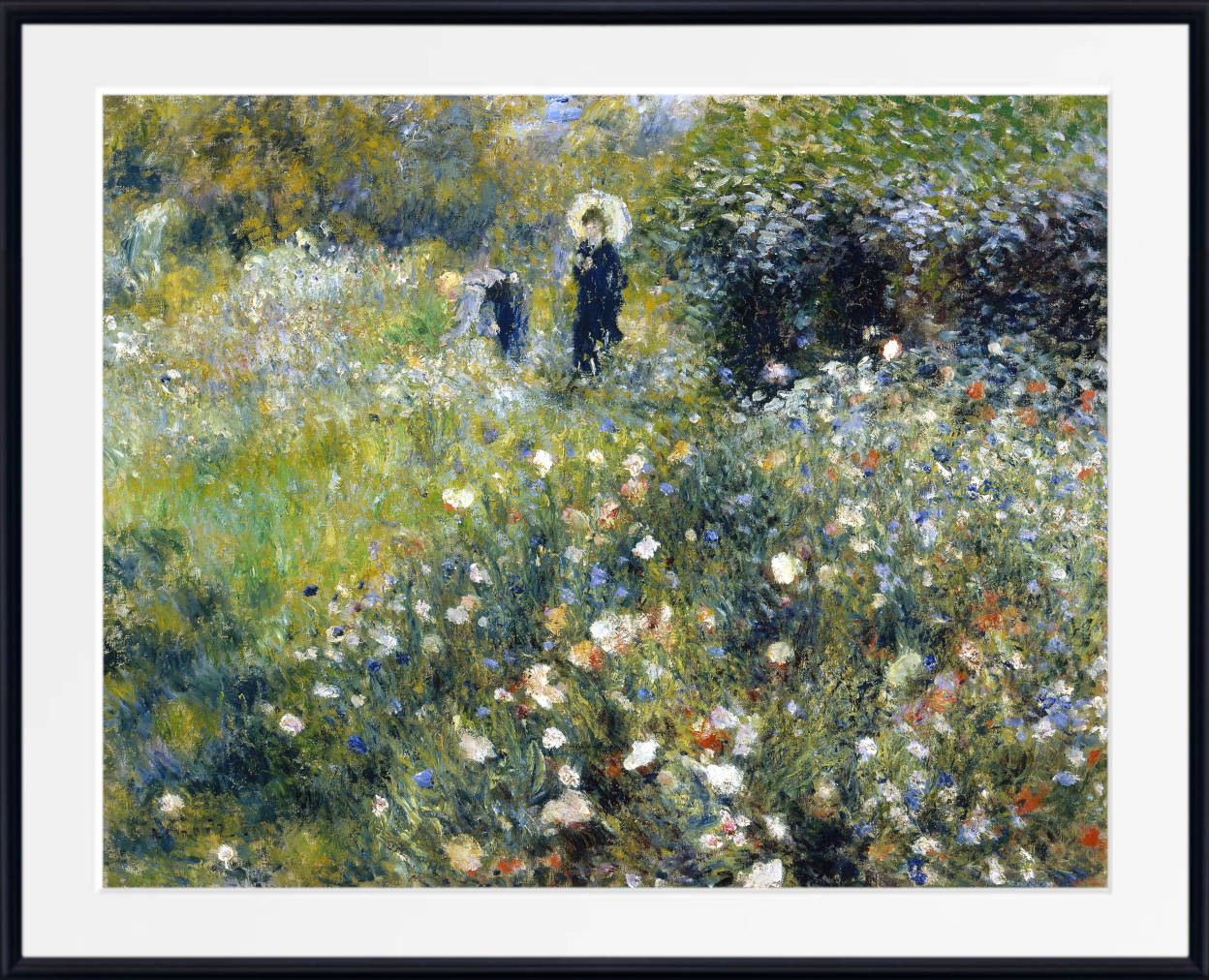

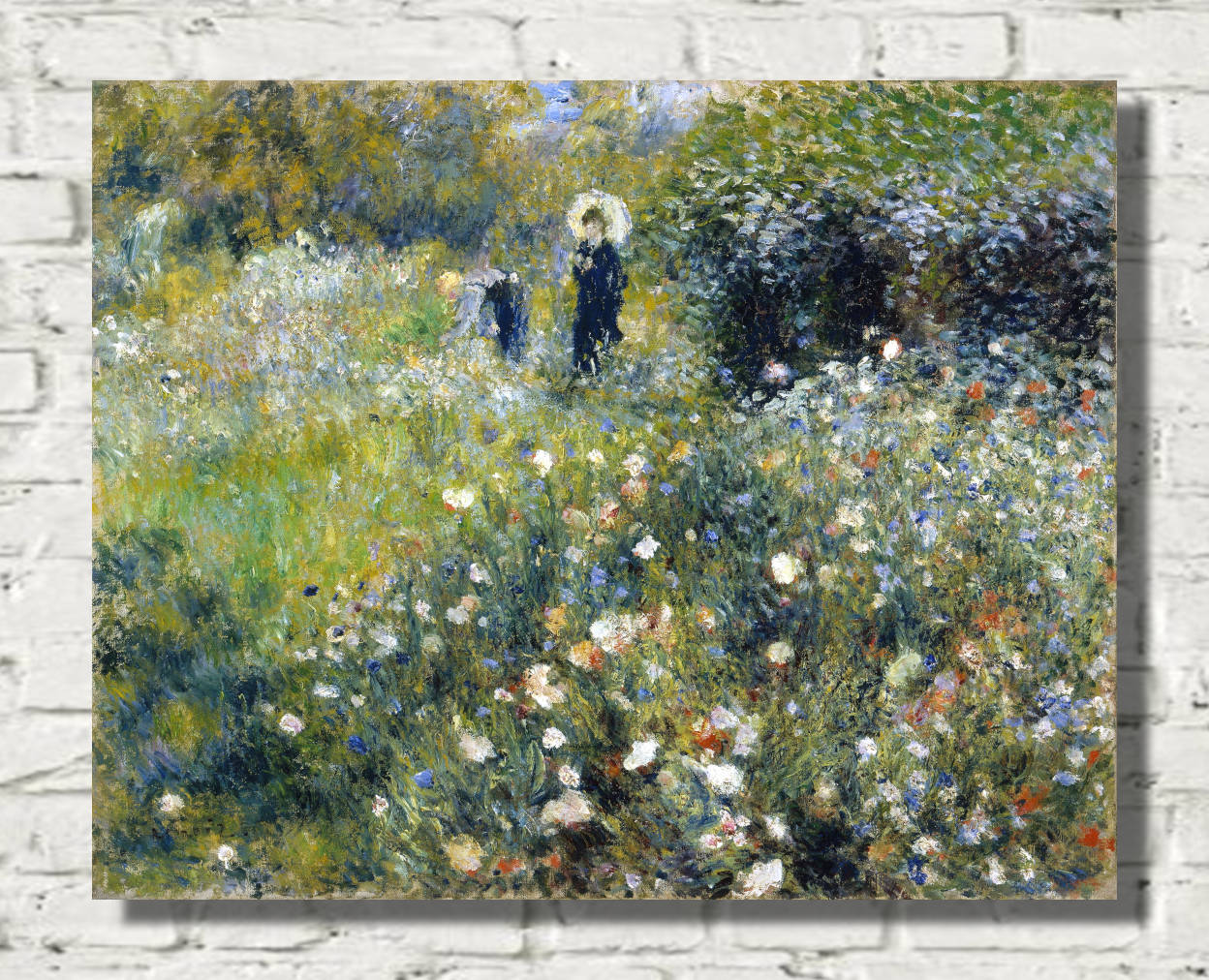

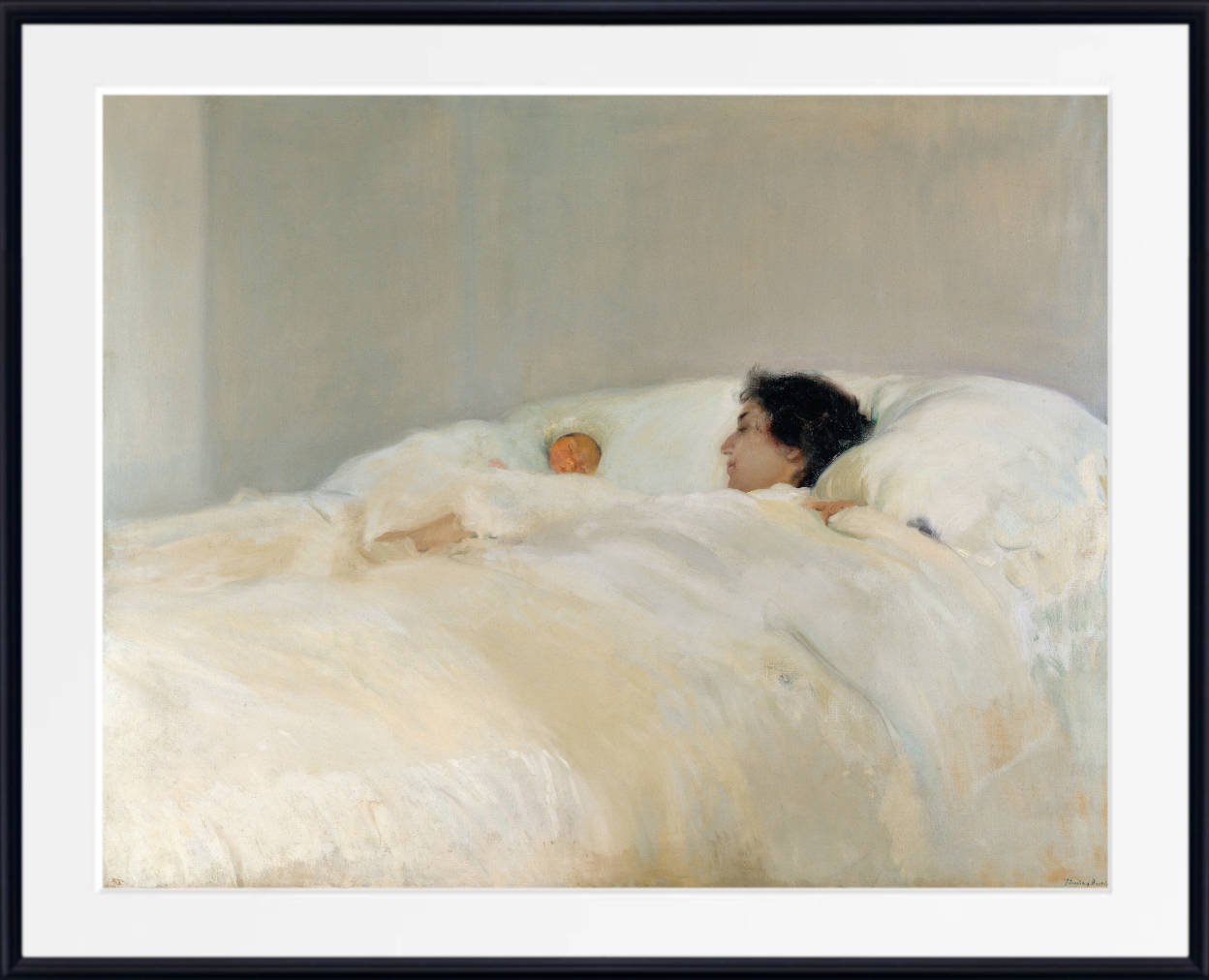

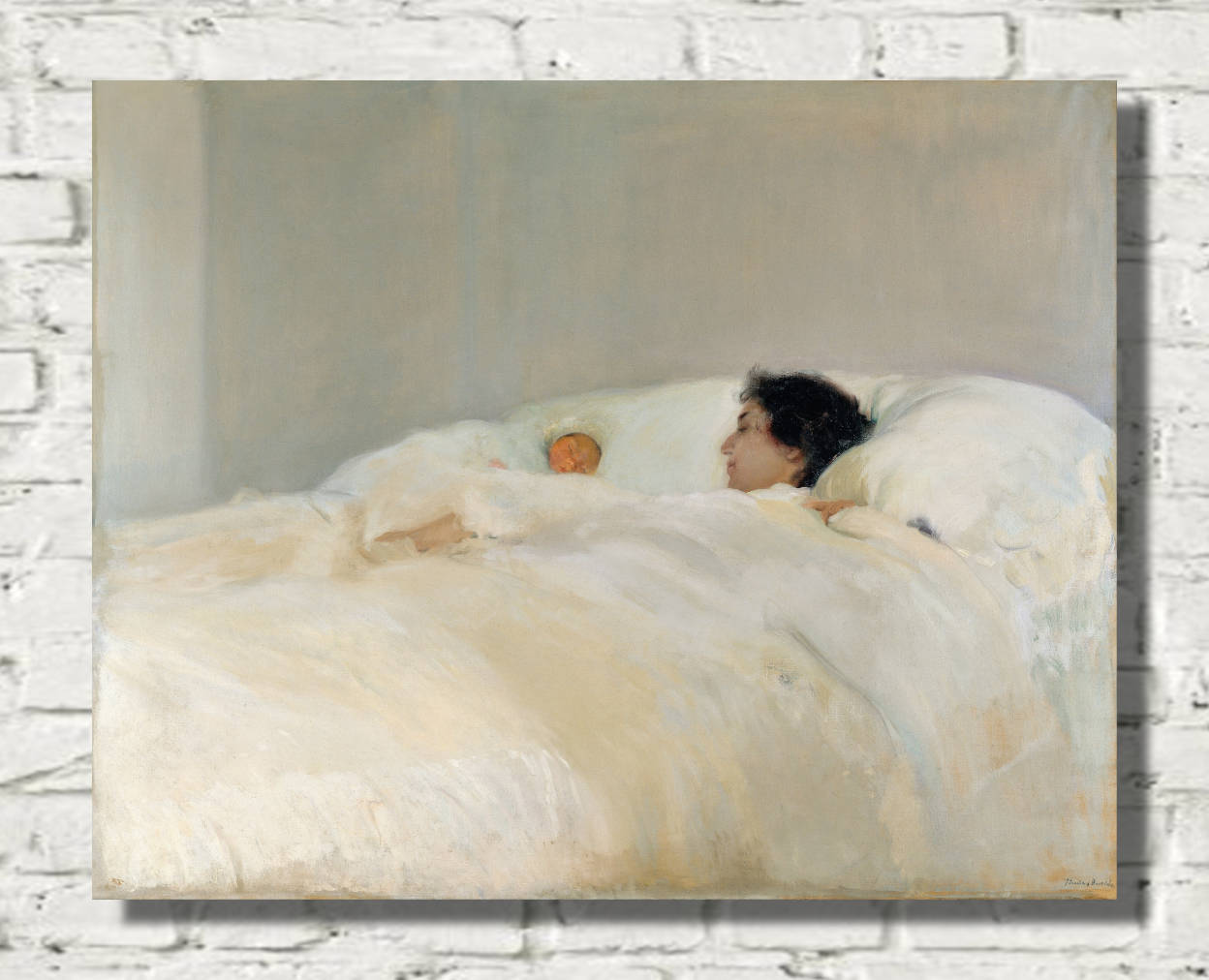

Whereas the male Impressionists painted figures mainly within the public setting of the city, Berthe Morisot concentrated on the private lives of women in late-19th-century society. The first woman to exhibit with the Impressionists, she created rich compositions that highlight the domestic, highly personal sphere of feminine society, often emphasizing the maternal bond between mother and child, as in The Cradle (1872). Together with Mary Cassatt, Eva Gonzalès, and Marie Bracquemond, she is considered one of the four central female figures of the Impressionist movement. Cassatt was an American painter who moved to Paris in 1866 and began exhibiting with the Impressionists in 1879. She depicted the private sphere of the home but also represented woman in the public spaces of the newly modernized city, as in her masterwork At the Opera (1879). Her paintings feature a number of innovations, including the flattening of three-dimensional space and the application of bright, even garish colors in her paintings, both of which heralded later developments in modern art.

Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, Mary Cassatt (1878)

The Spread of Impressionism

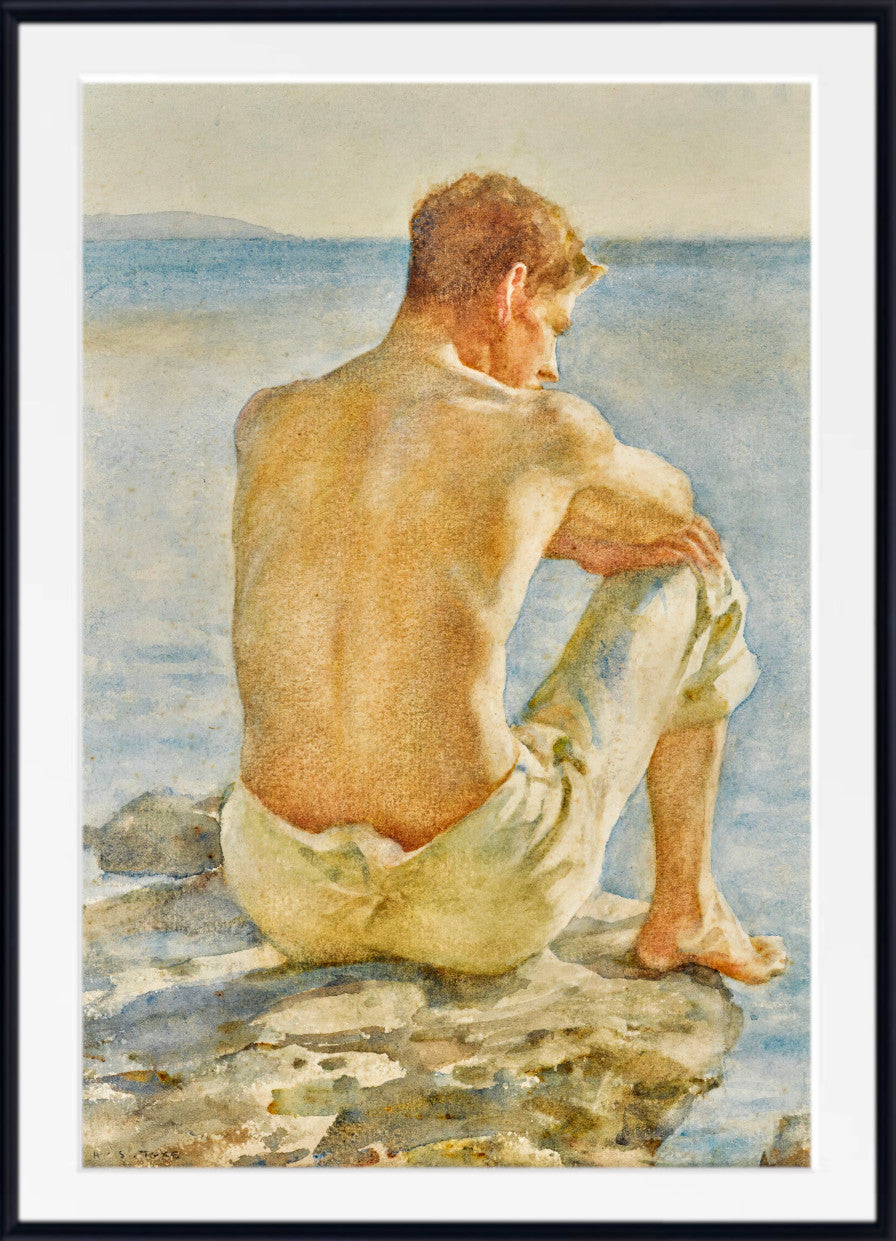

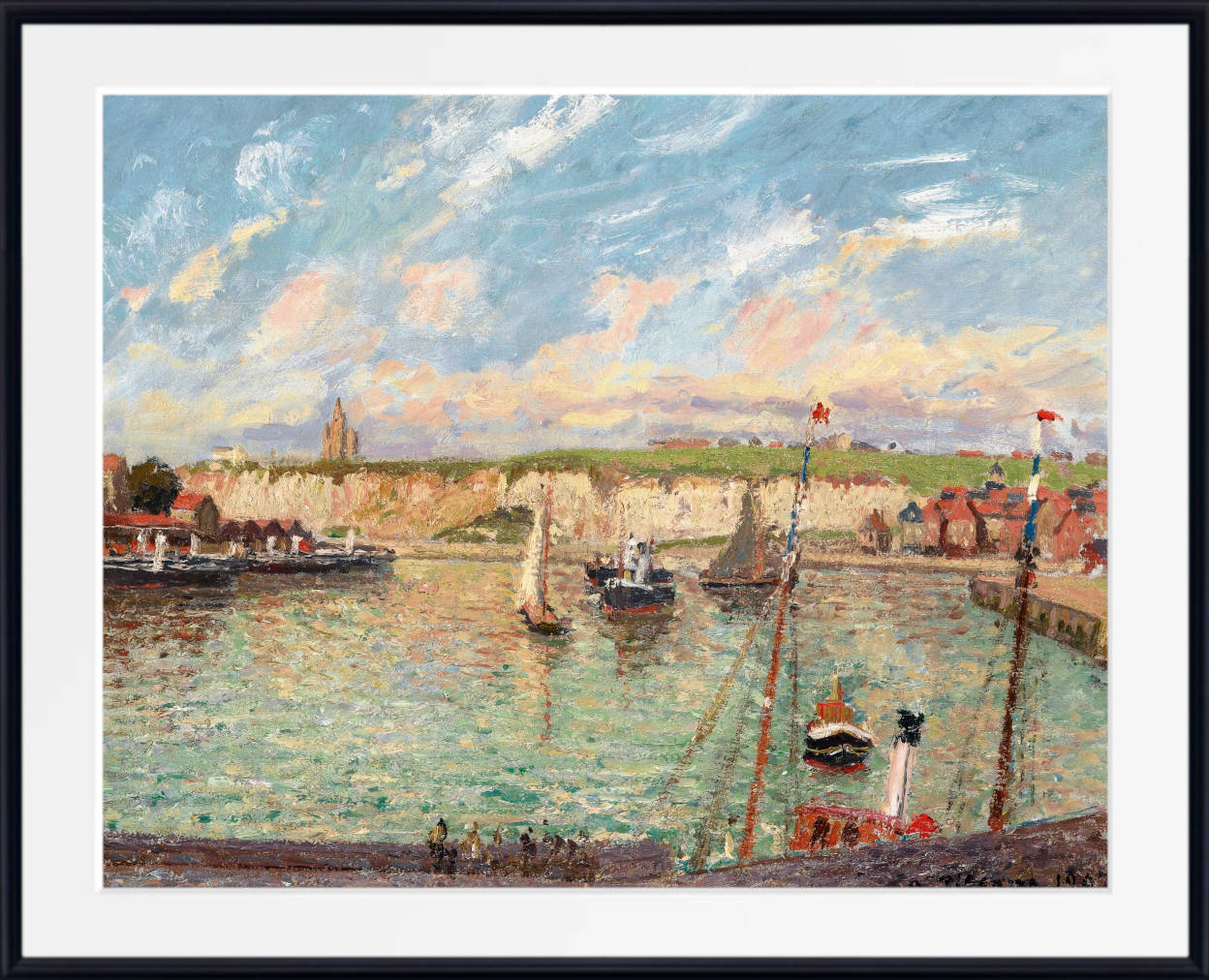

Even as Impressionism in France was being overtaken by the advances of the Post-Impressionists, its legacy was travelling across continents. Amongst the most famous of the international Impressionist groupings was the American Impressionist movement, associated not just with Cassatt but with painters such as William Merritt Chase, who applied Impressionist techniques to the landscapes and bourgeois, cosmopolitan milieu of late-nineteenth-century US society; Childe Hassam, famous for his vivid coastal and city scenes; and Maurice Prendergast, who forged a distinctive North-American Post-Impressionist style. Other notable schools of Impressionism in the Anglophone world include the Australian Impressionist school, associated with the work of Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, amongst others, and with the dusty color palettes of its Antipodean climate and terrain. Particularly significant was the British Impressionist movement of the late-nineteenth century. James Abbott McNeill Whistler, an American expatriate in London, pioneered a loose, liquid style of painting which, in his famous Nocturne series, brilliantly conveyed the gloom and glamor of nightfall on the River Thames. Philip Wilson Steer, meanwhile, became associated with the Impressionist seascape, in particular with works focusing on the landscapes of Cornwall and the South-west of England, while the Scot William McTaggart produced stormier marine scenes, redolent of the wilder coastal landscapes of his home country. Other important Impressionist schools emerged all over Europe, notably in Germany, where Max Liebermann was one of the leading figures of the movement, and also in Holland, Belgium, and Denmark.

Morning at Breakwater, Shinnecock William Merritt Chase (1897)

The White Symphony- Three Girls, James McNeill Whistler

Impressionist Cityscapes

Since the movement was deeply embedded within Parisian society, Impressionism was greatly influenced by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann's renovation of the city in the 1860s. The urban project, also referred to as "Haussmannization," sought to modernize the city and largely centered in the construction of wide boulevards which became hubs of public social activity. This reconstruction of the city also led to the rise of the idea of the flâneur: the idler or lounger who roams the public spaces of the city, observing life while remaining detached from the crowd. In many Impressionist paintings, the detachment of the flâneur is closely associated with modernity and the estrangement of the individual within the metropolis. These themes of urbanity are depicted in the work of Gustave Caillebotte, a later proponent of the Impressionist movement, who focused on panoramic views of the city and the psychology of its citizens. Although more realistic in style than other Impressionists, Caillebotte's images, such as Paris, Rainy Day (1877), express the artist's reaction to the changing nature of society, showing a flaneur in his characteristic black coat and top hat strolling through the open space of the boulevard while gazing at passersby. Other Impressionists depicted the fleeting qualities of movement and light within the metropolis, as in Monet's Boulevard des Capucines (1873) and Pissarro's The Boulevard Montmarte, Afternoon (1897). Similarly, these works emphasize the geometrical arrangement of public space through the careful delineation of buildings, trees, and streets. By applying crude brushstrokes and impressionistic streaks of color, the Impressionists evoked the rapid tempo of modern life as a central facet of late-19th-century urban society.

Halévy Street, View from the Sixth Floor, Gustave Cailllebotte

Boulevard des Capucines, Claude Monet

The Lady With Fans, is a prominent piece of impressionist artist Edouard Manet, illustrating the society of the 19th century. Manet drew a series of painting with the common theme of women displayed upon sofas, showcasing the beautiful femininity each one holds.

A carefully curated collection of the best works of the impressionist artists is available HERE