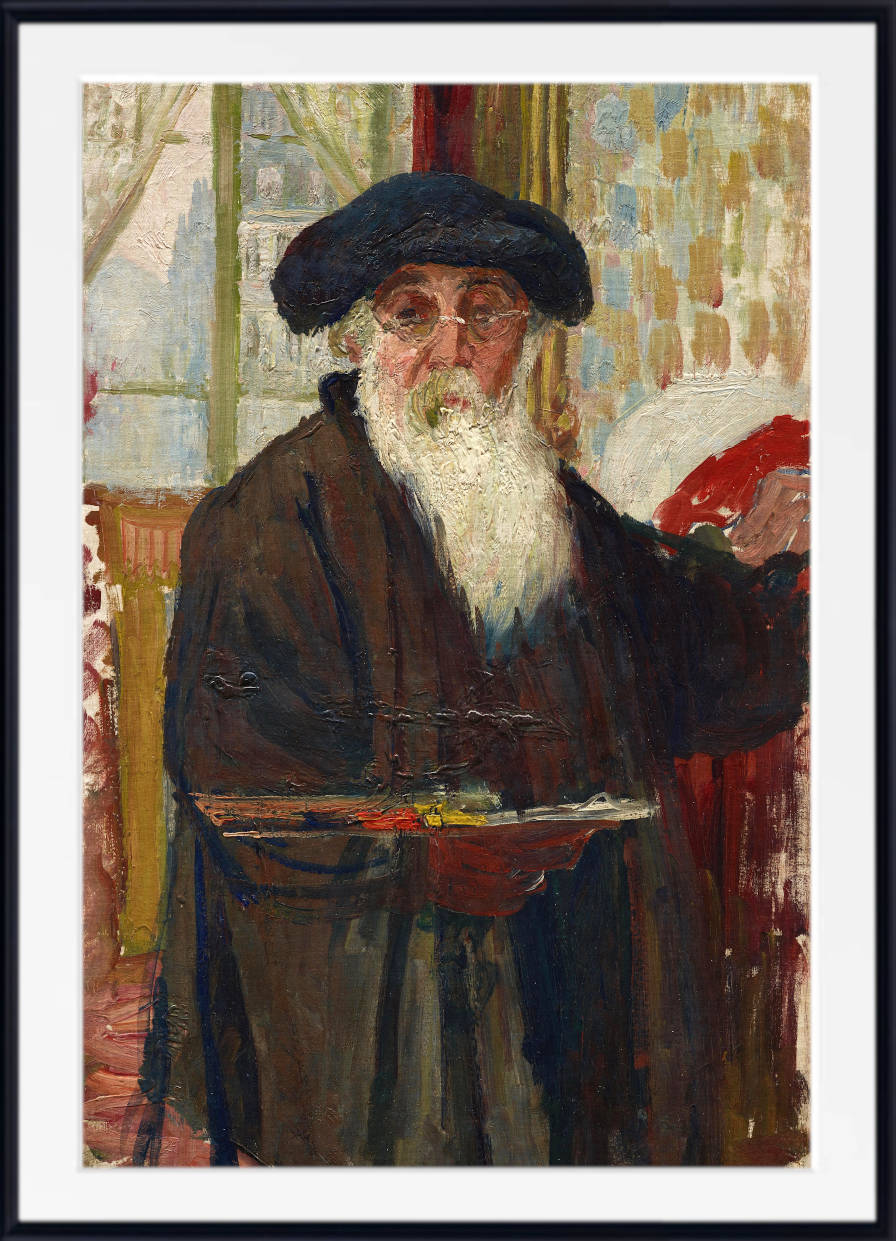

Théodule Ribot

Théodule-Augustin Ribot (August 8, 1823 – September 11, 1891) was a French realist painter and printmaker.

He was born in Saint-Nicolas-d'Attez, and studied at the École des Arts et Métiers de Châlons before moving to Paris in 1845. There he found work decorating gilded frames for a mirror manufacturer. Although he received a measure of artistic training while working as an assistant to Auguste-Barthélémy Glaize, Ribot was mostly self-taught as a painter. After a trip to Algeria around 1848, he returned in 1851 to Paris, where he continued to make his living as an artisan. In the late 1850s, working at night by lamplight, he began to paint seriously, depicting everyday subjects in a realistic style.

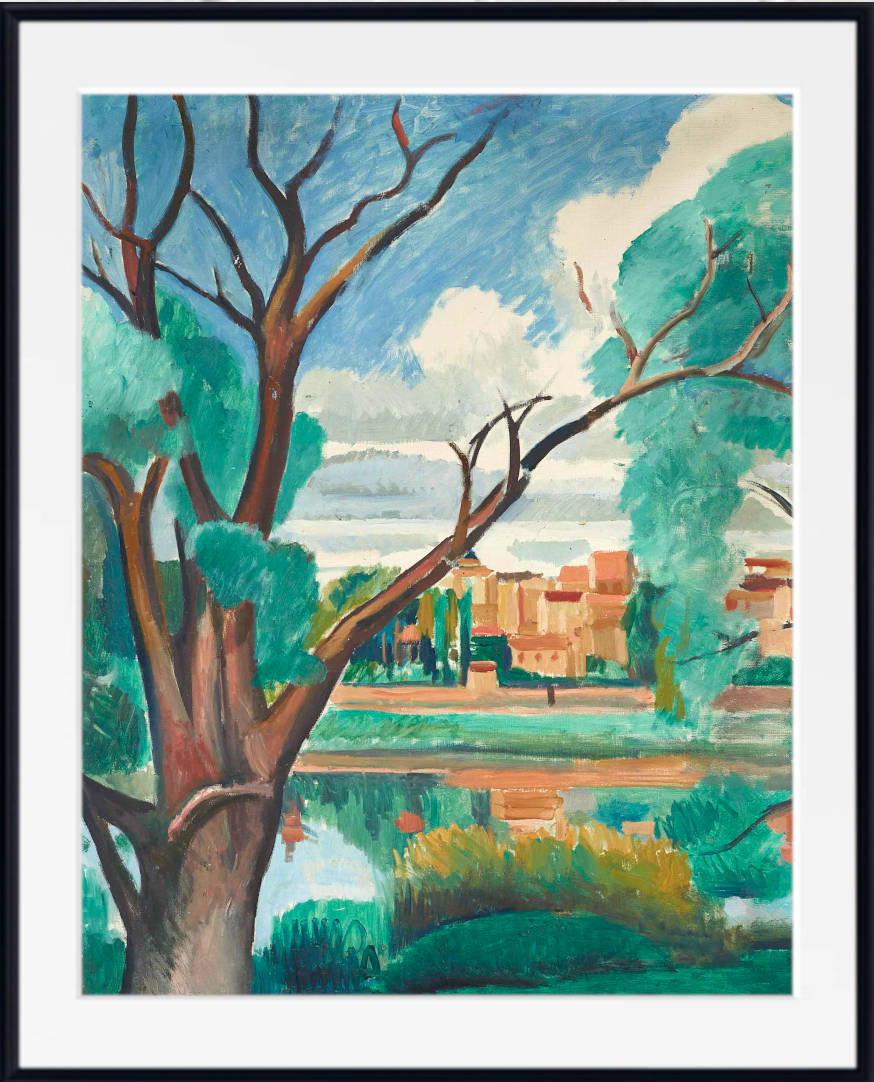

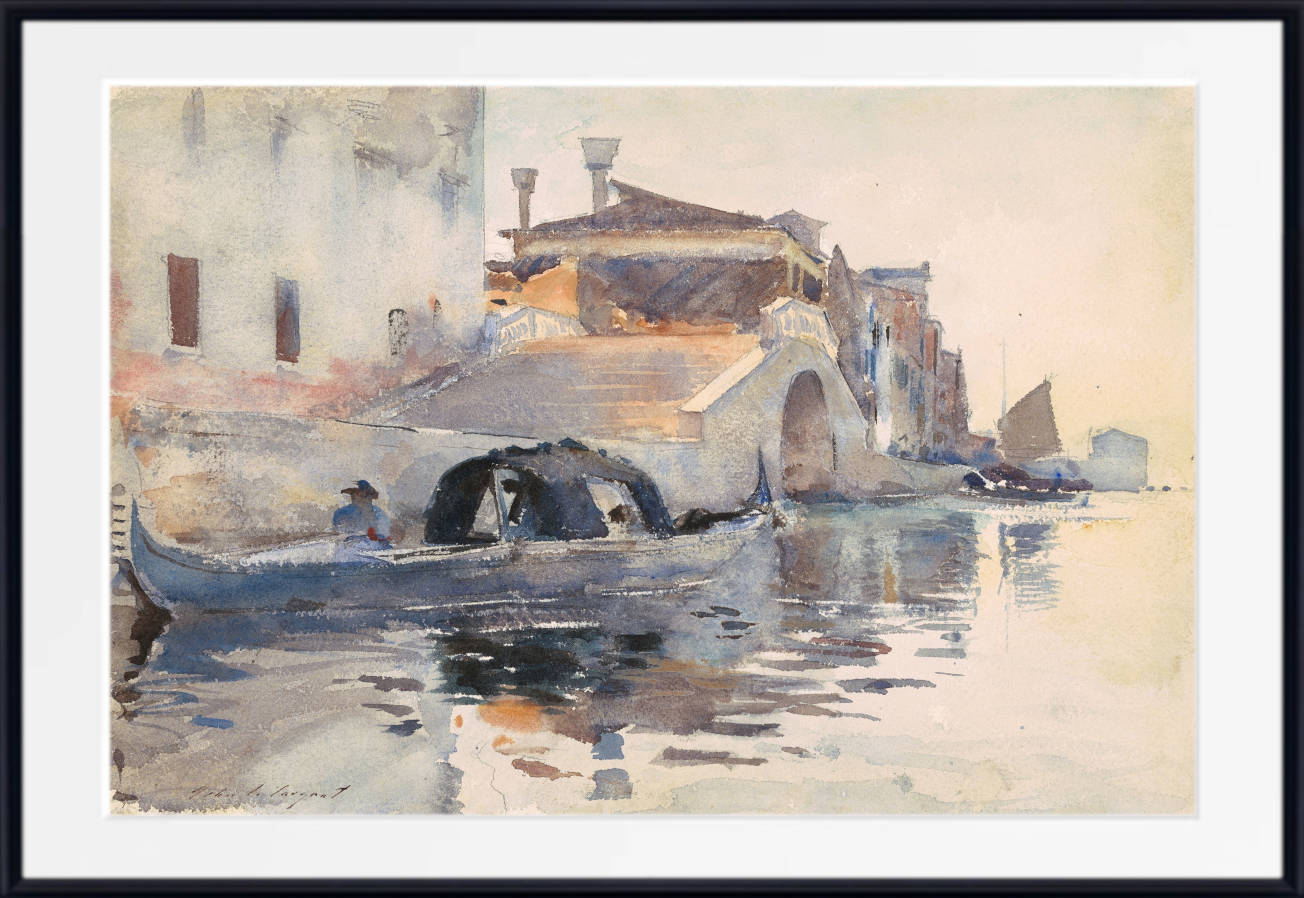

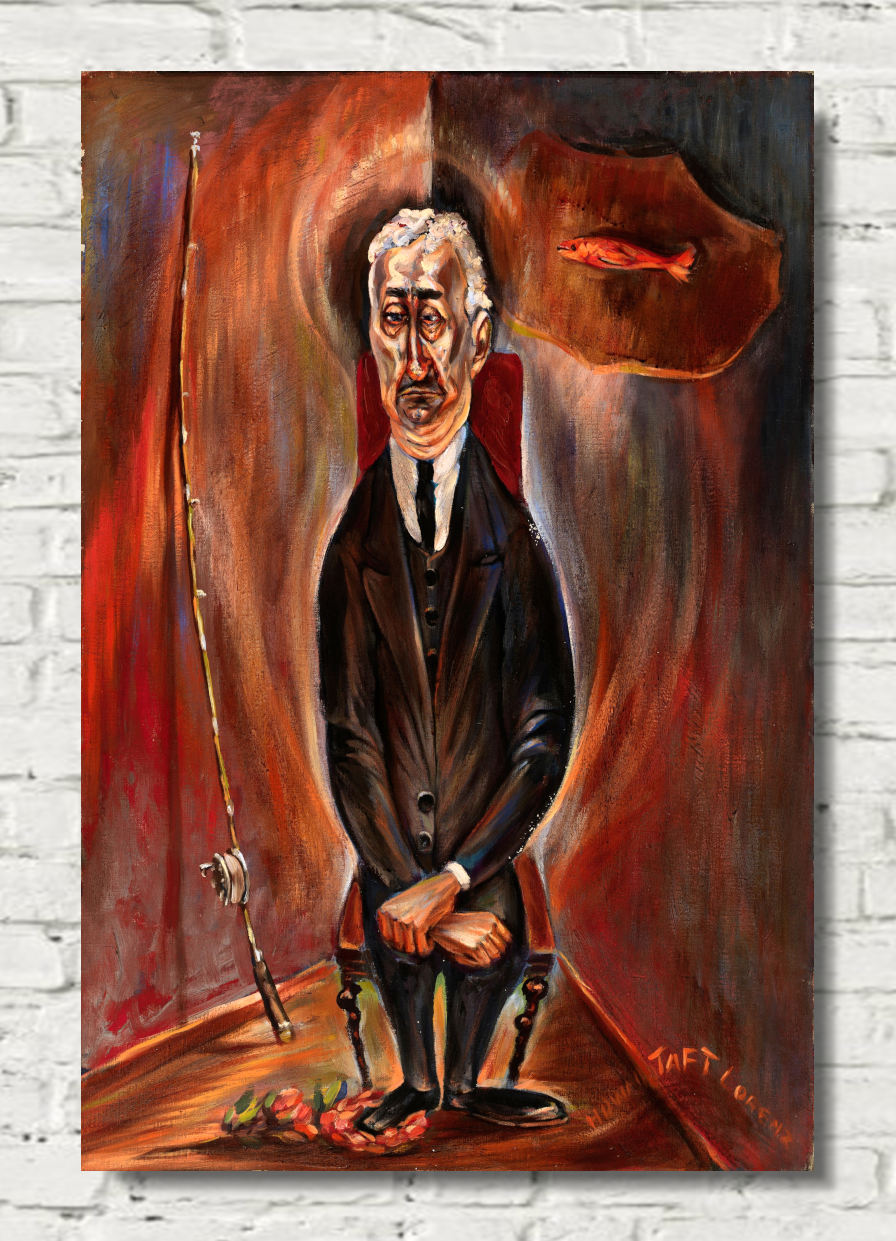

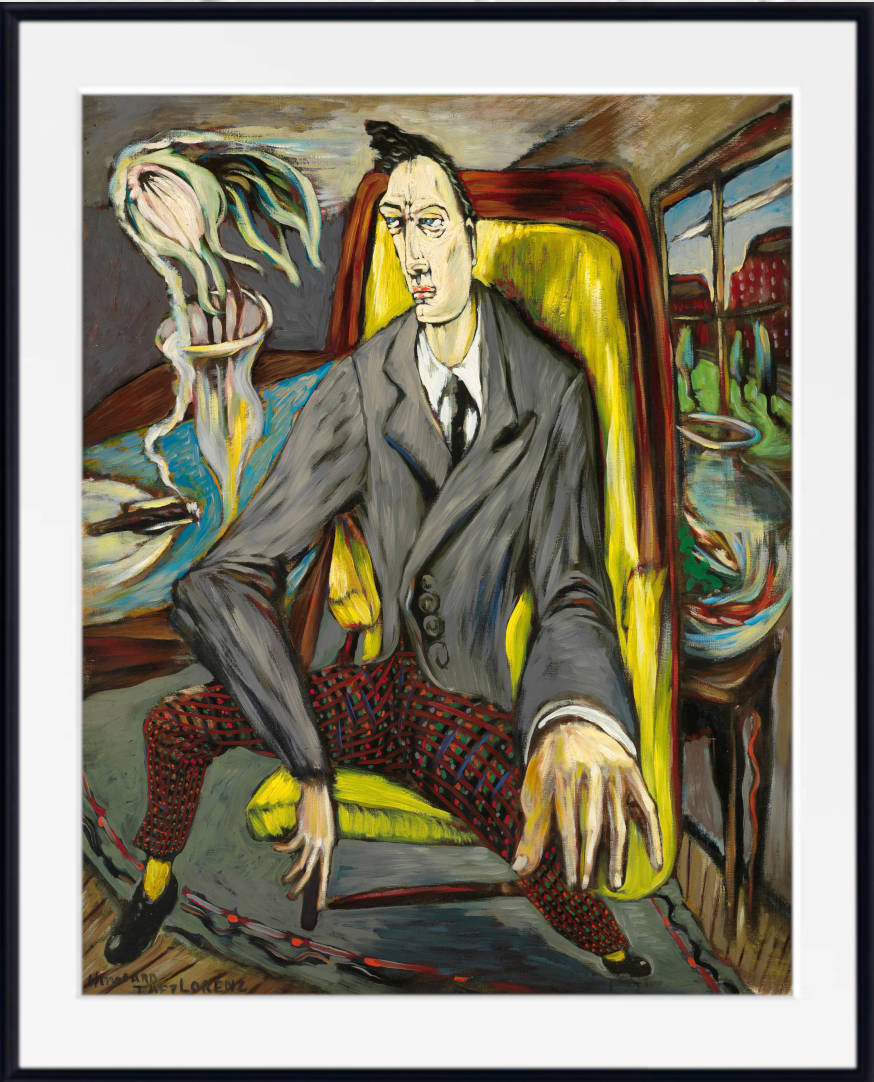

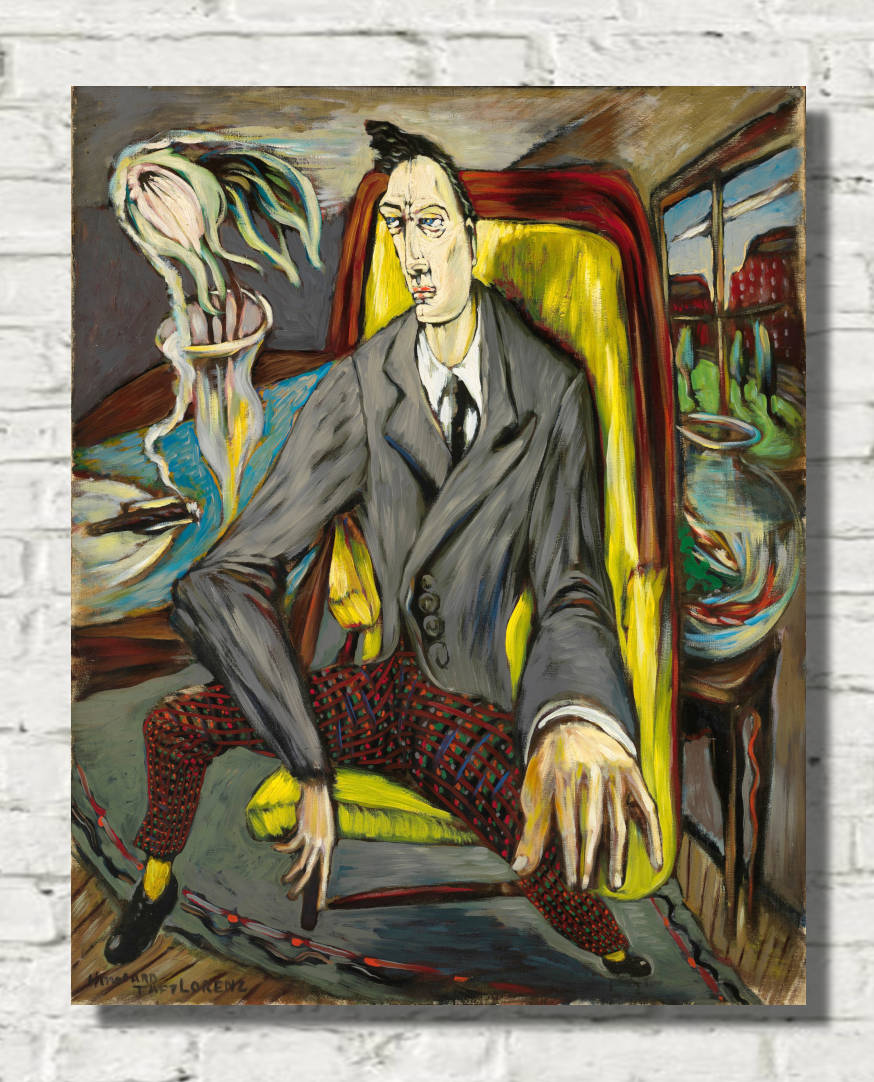

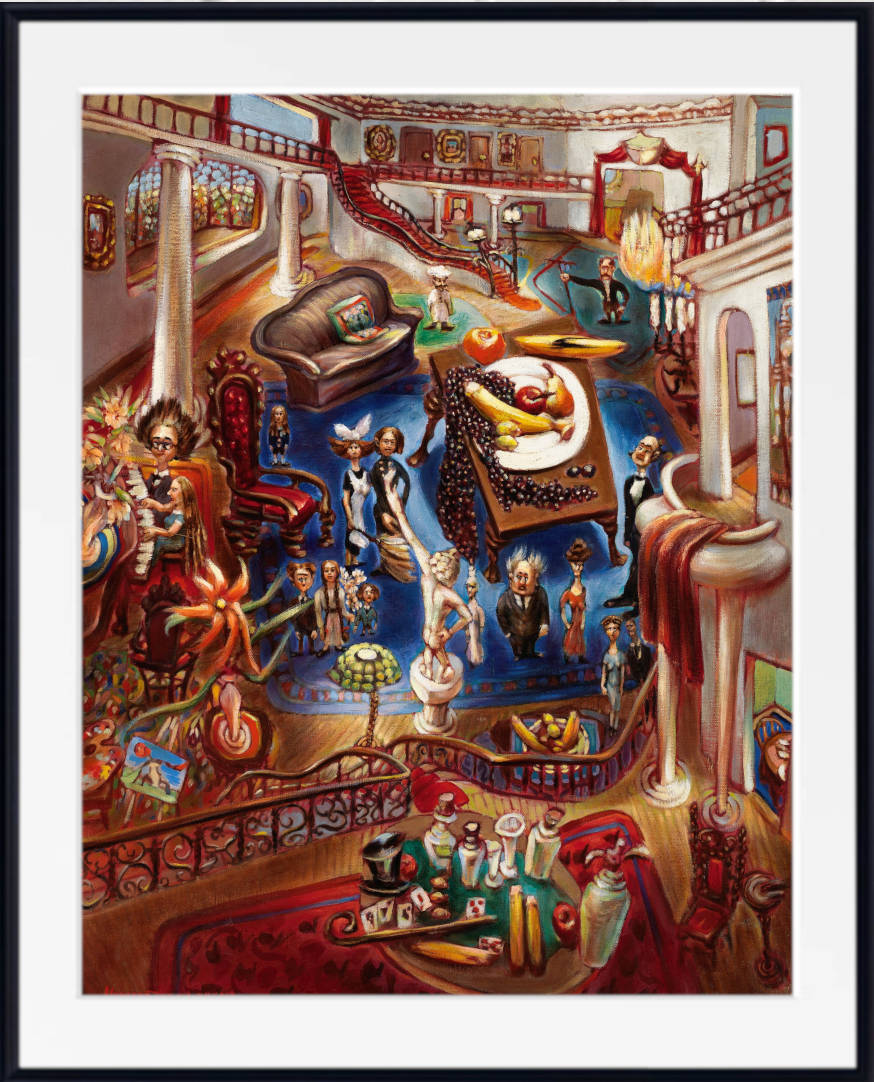

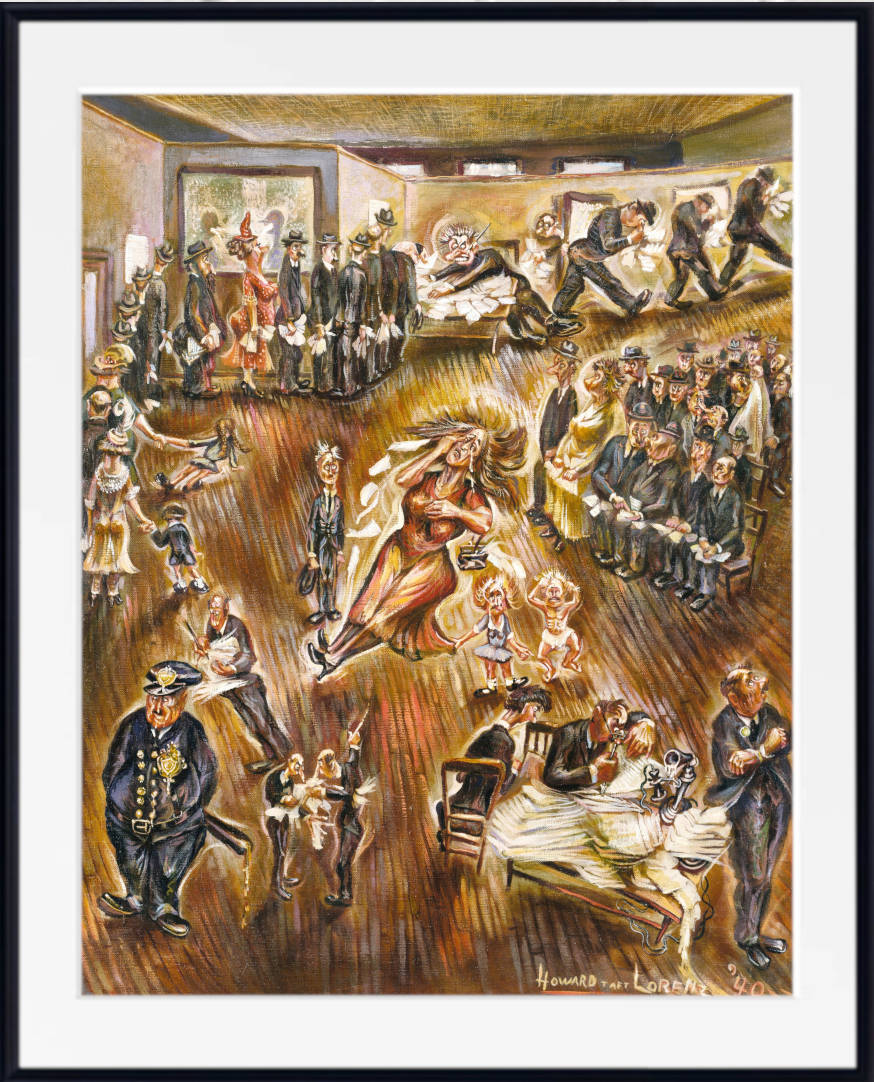

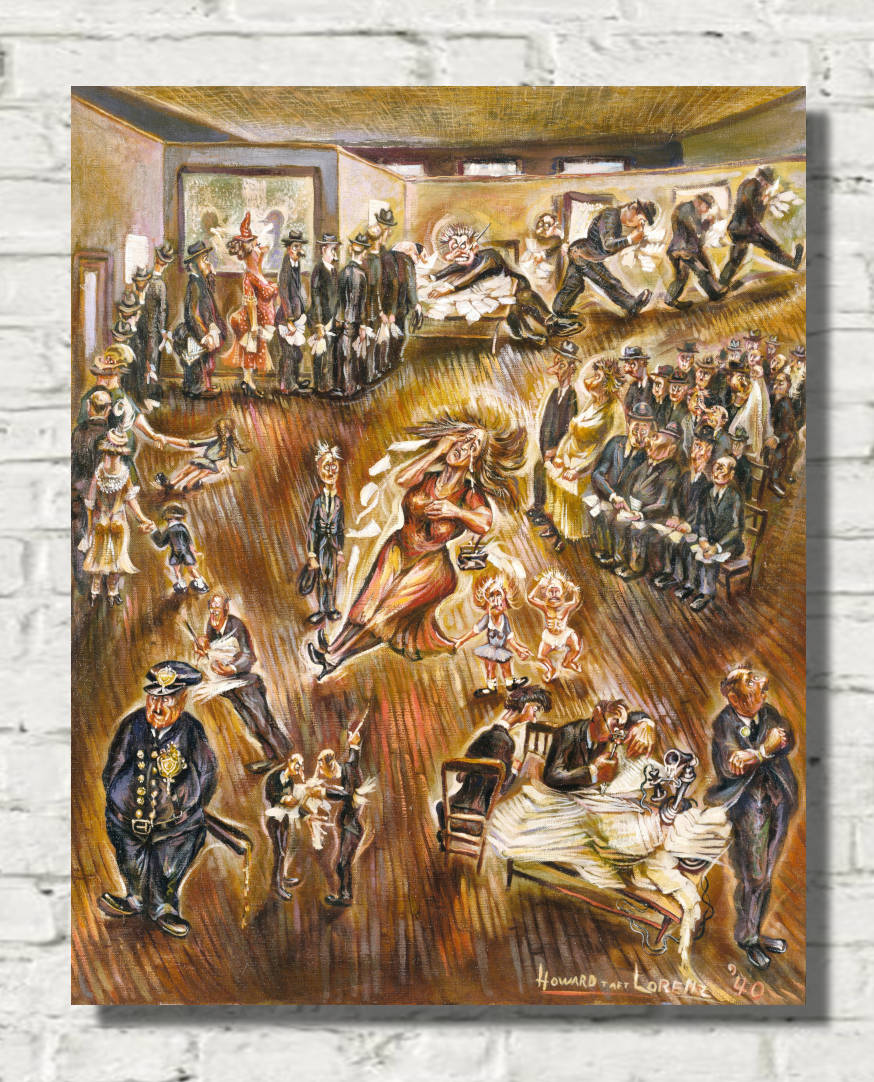

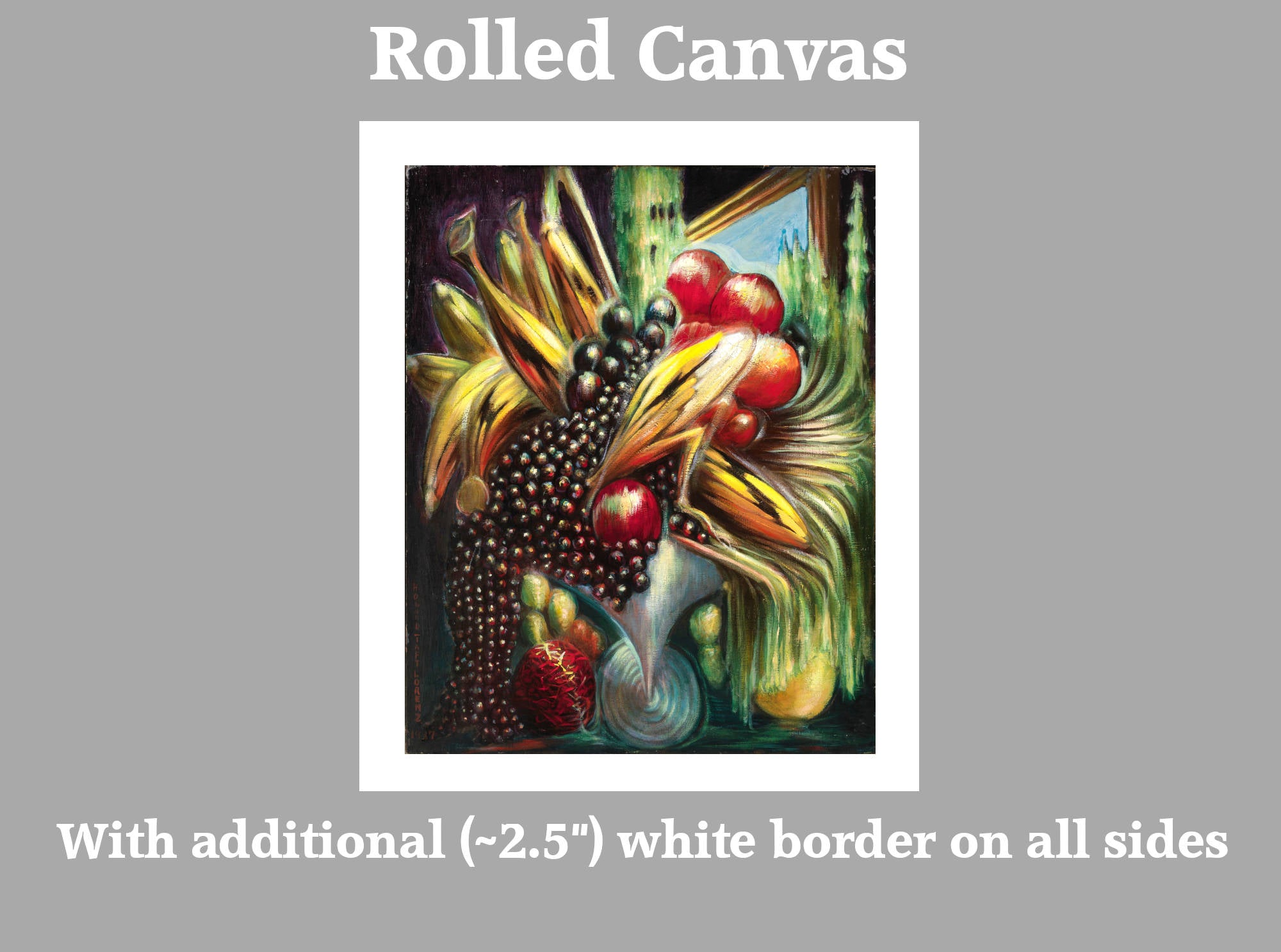

Ribot worked in at least three mediums, oil paint, pencil or crayon draughtsmanship and etching. Some drawings were complete works, others fragmentary but powerful preparations for painted canvases. The etchings, of which there are only about a couple of dozen, are of the middle period of his practice; they show a diversity of method as well as of theme.

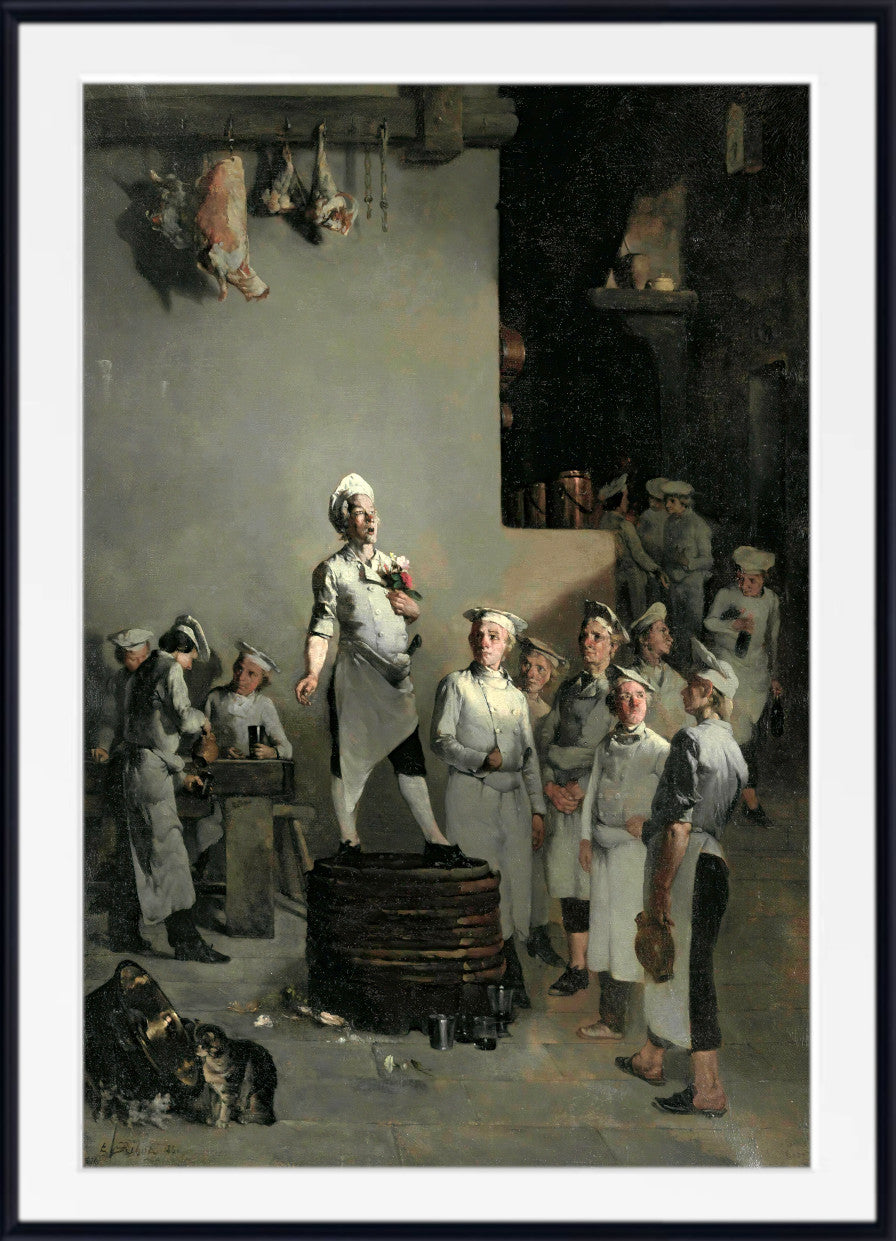

He made his Salon debut in 1861 with four paintings of kitchen subjects.[2] Collectors purchased the works, and his paintings in the Salons of 1864 and 1865 were awarded medals.

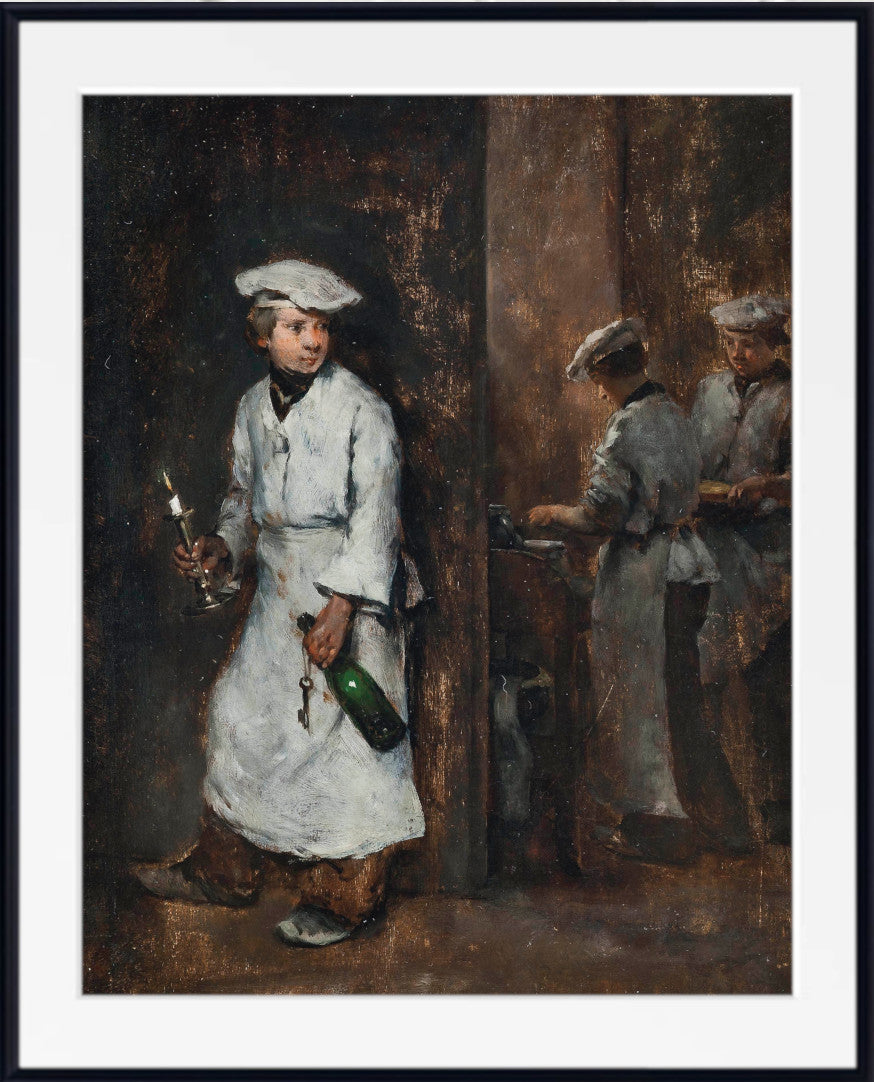

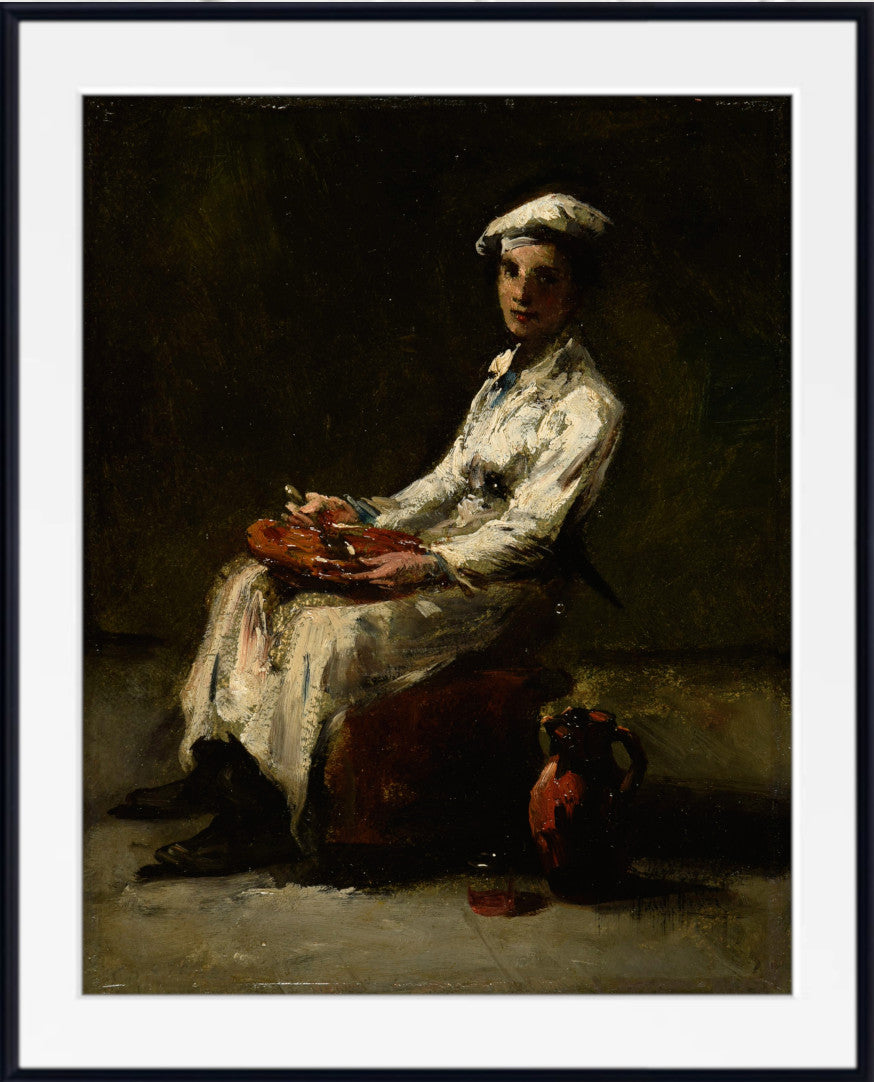

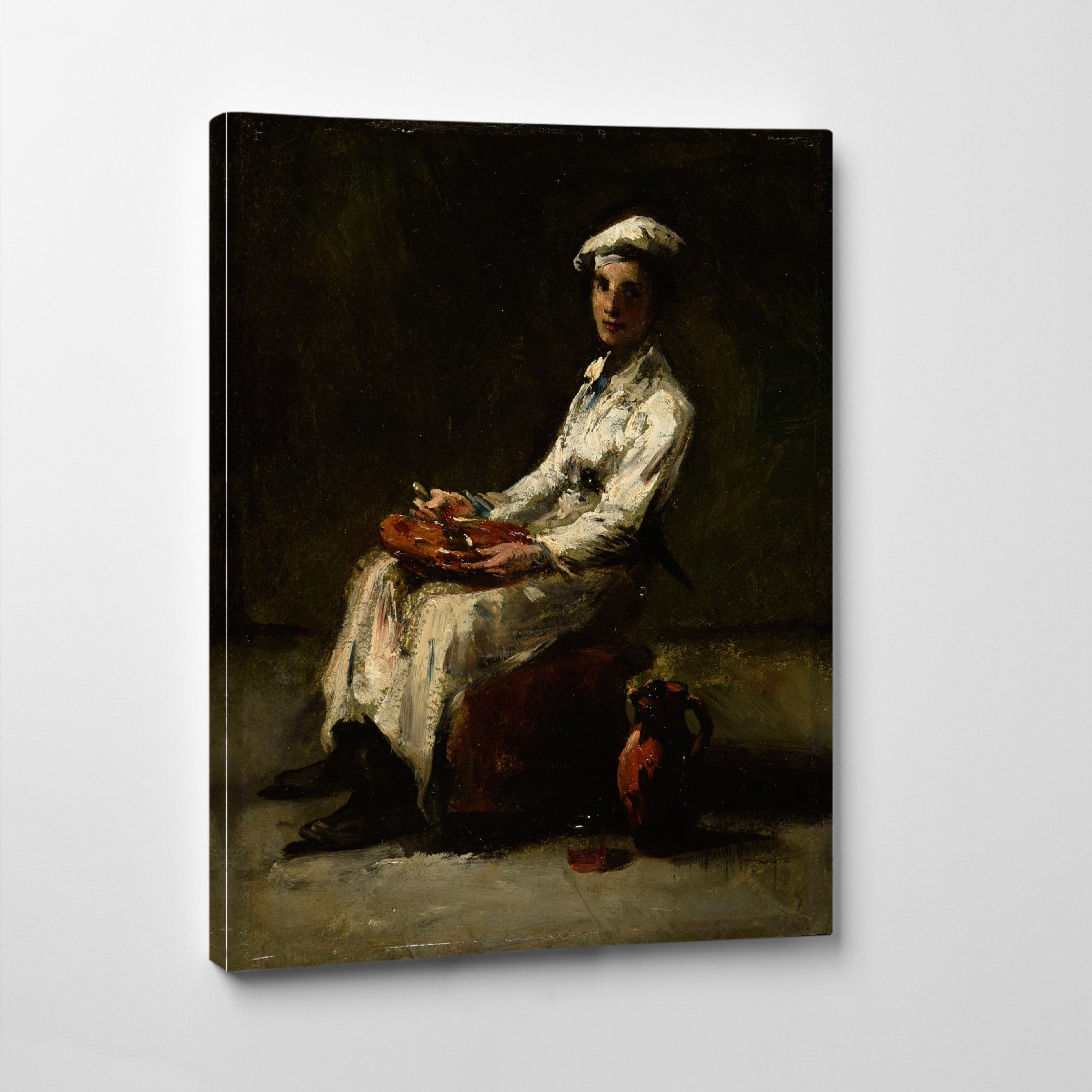

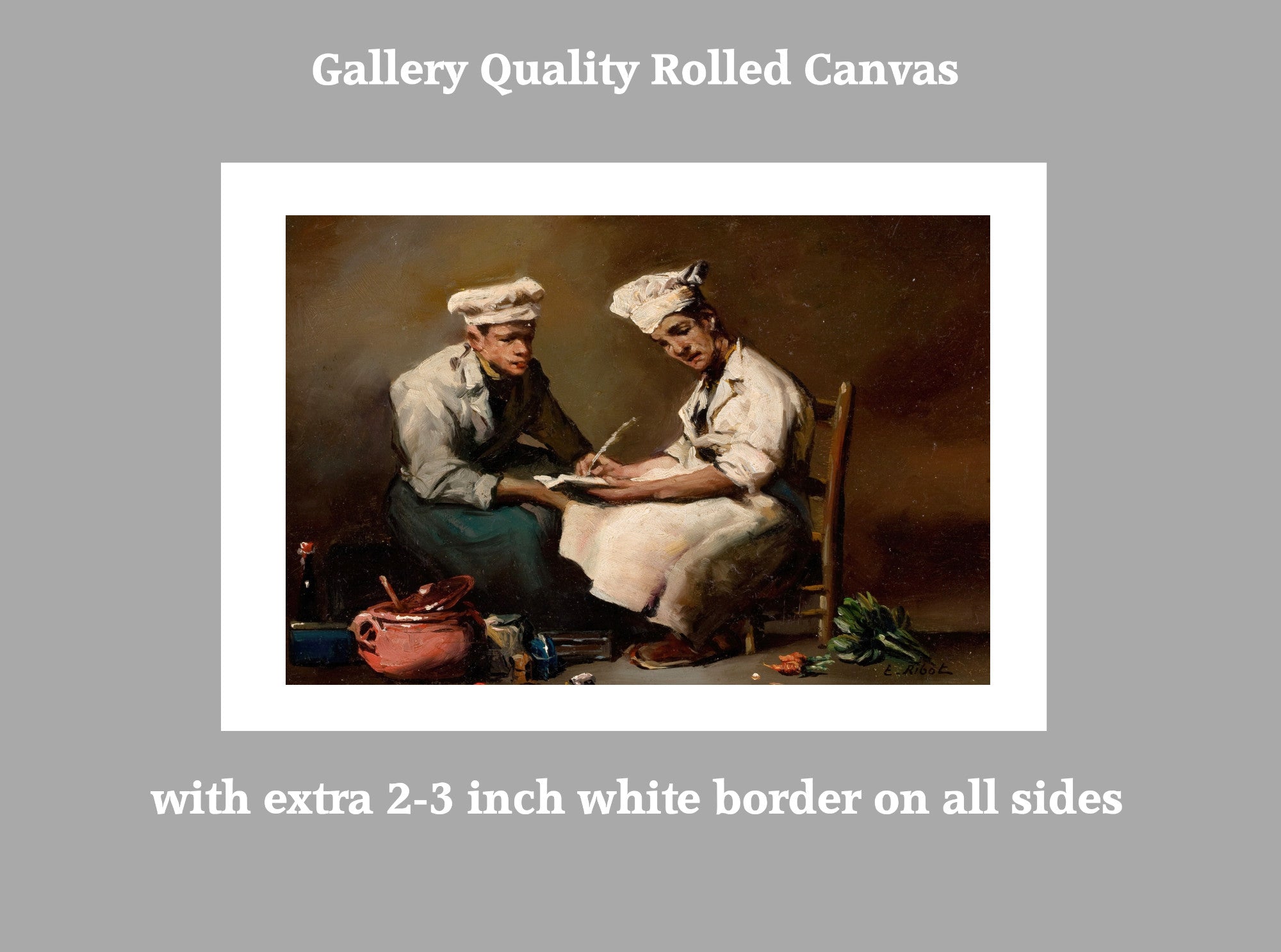

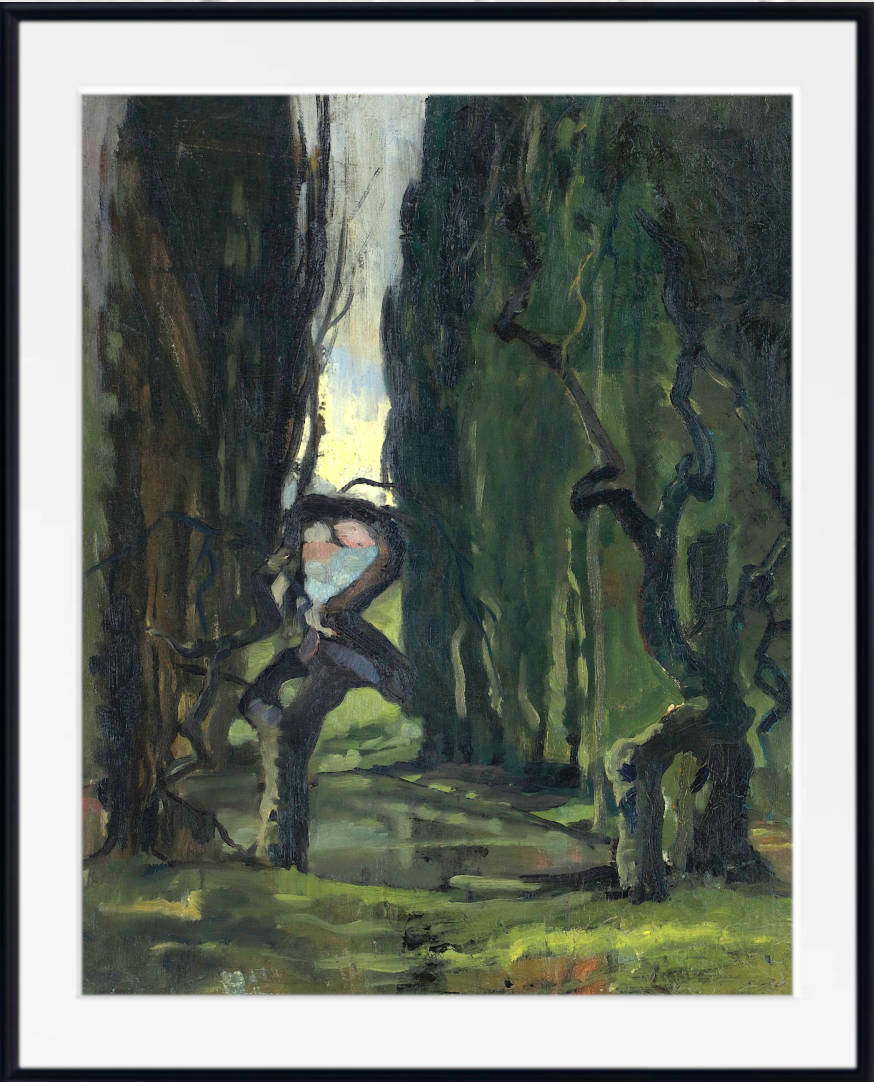

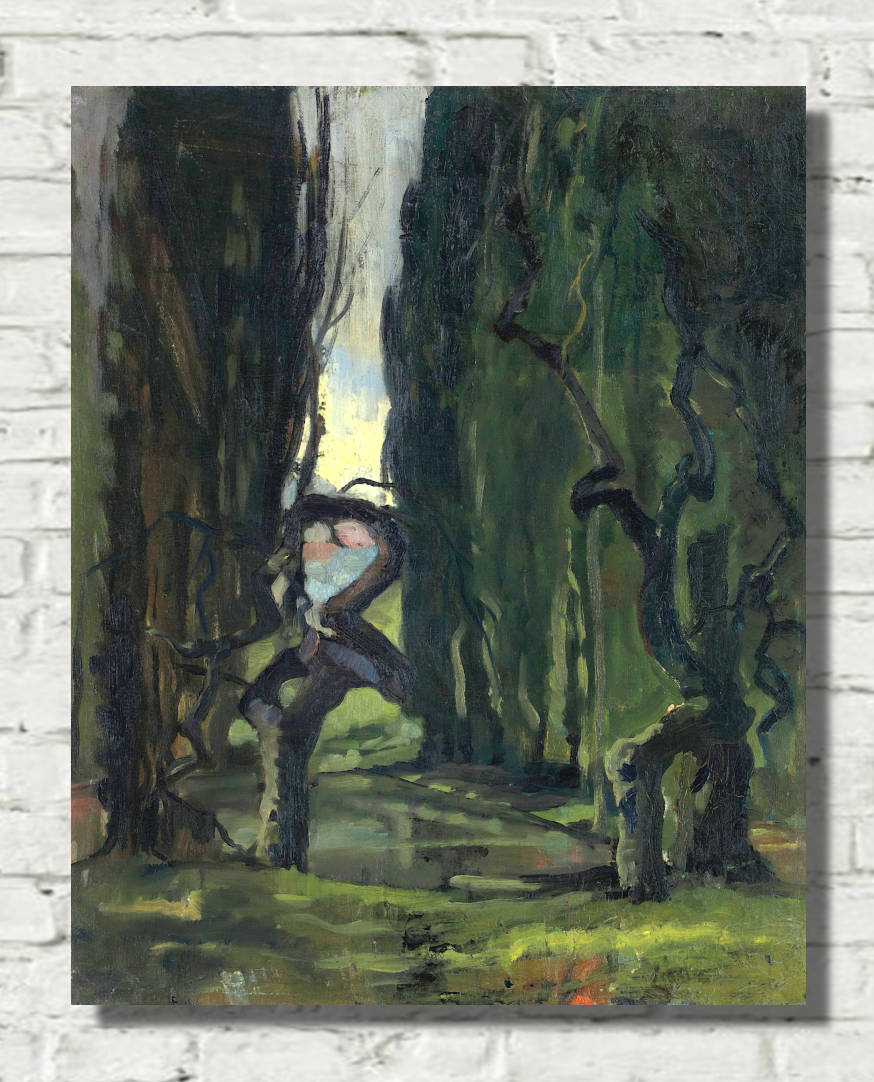

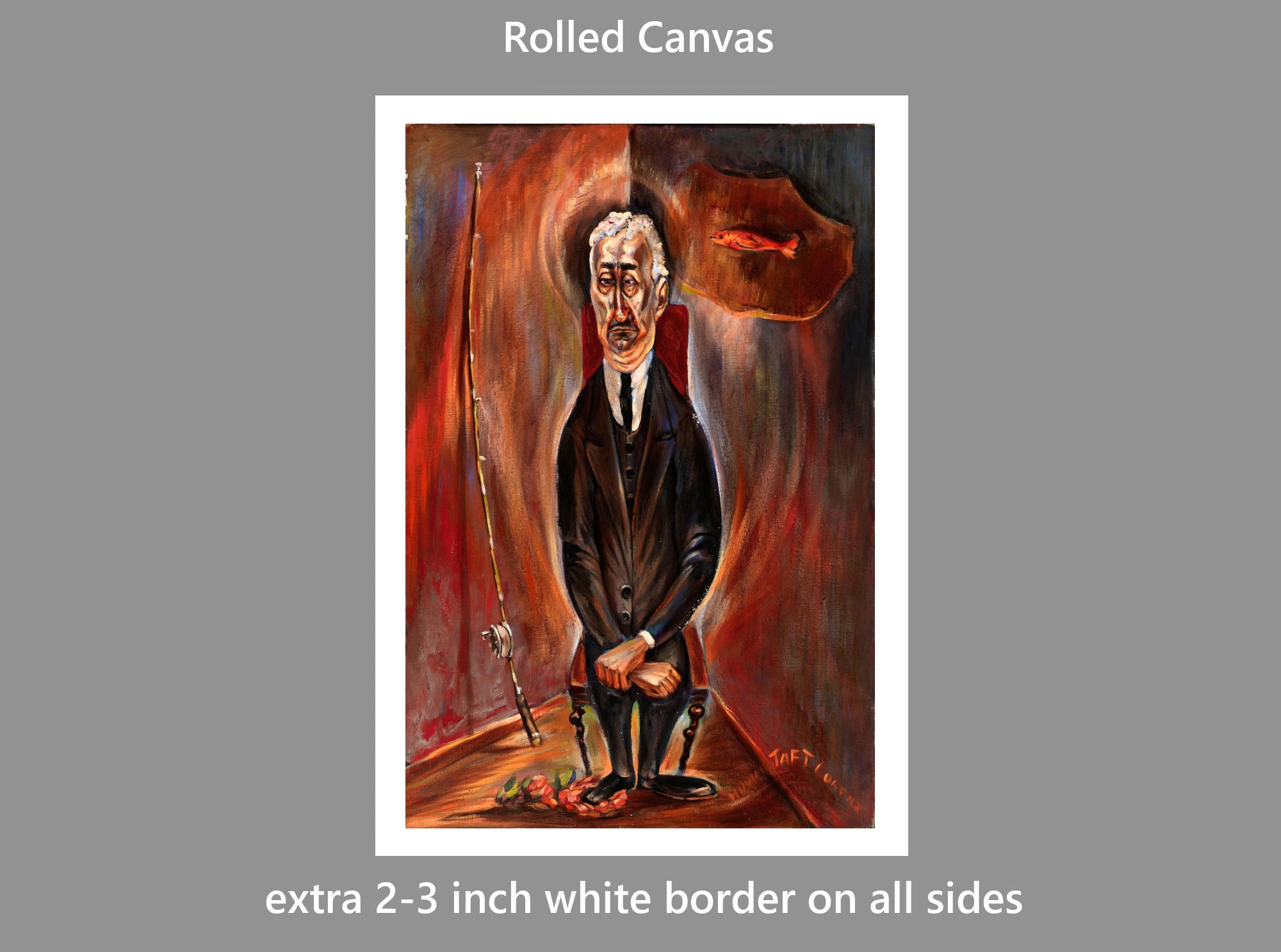

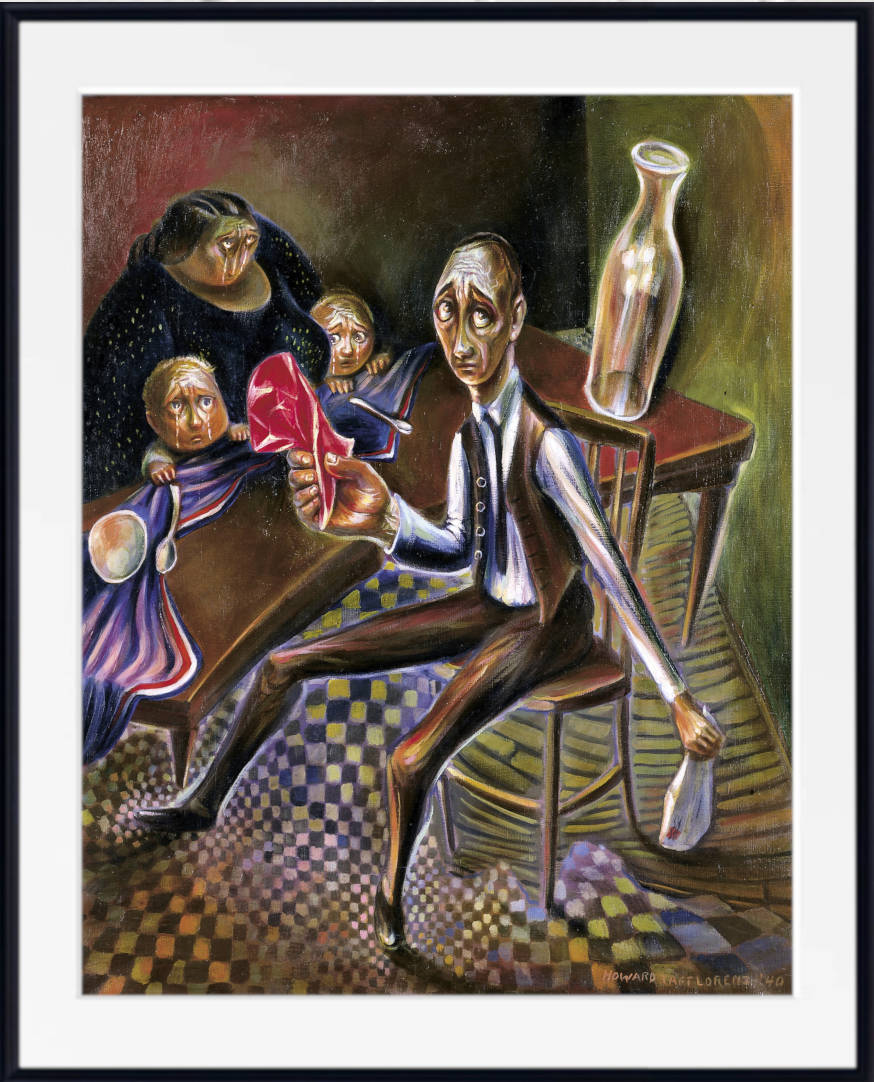

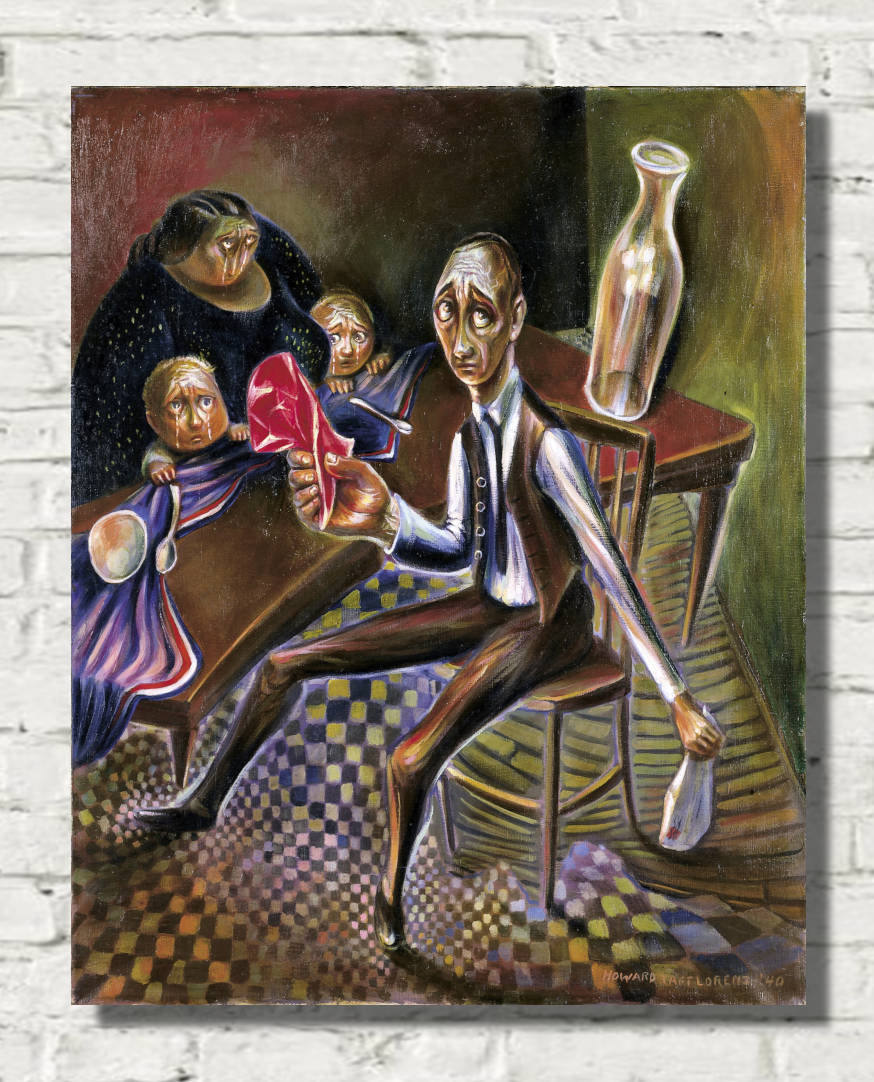

Ribot painted domestic genre works, still-lifes, portraits, as well as religious scenes, such as his Salon success St. Sebastian, Martyr (1865). The earlier work was drier and austere but still with an intensity of conception and presentation; later works were freer and broader. His preference was for painting directly from nature, emphasizing the contrasts of light and dark. His use of chiaroscuro to suggest psychological states grew from his admiration for Spanish and Dutch baroque masters such as Ribera and Rembrandt, an enthusiasm shared by his contemporaries Courbet and Bonvin. Members of Ribot's family are the likely models for many of his figure compositions, in which the subjects engage in humble activities, such as preparing meals or gathering in groups to read to each other. The light draws attention to faces and hands, which emerge sharply from dimly lit surroundings.

Although the realism of Ribot's work aligns him with the most progressive artists of the generation preceding the Impressionists, he was no revolutionary, and his work met with a generally favorable response from the public and from critics.

In 1878 Ribot received the Légion d'honneur. At about this time, in ill health, he stopped painting and moved to Colombes, where he died in 1891.

He was born in Saint-Nicolas-d'Attez, and studied at the École des Arts et Métiers de Châlons before moving to Paris in 1845. There he found work decorating gilded frames for a mirror manufacturer. Although he received a measure of artistic training while working as an assistant to Auguste-Barthélémy Glaize, Ribot was mostly self-taught as a painter. After a trip to Algeria around 1848, he returned in 1851 to Paris, where he continued to make his living as an artisan. In the late 1850s, working at night by lamplight, he began to paint seriously, depicting everyday subjects in a realistic style.

Ribot worked in at least three mediums, oil paint, pencil or crayon draughtsmanship and etching. Some drawings were complete works, others fragmentary but powerful preparations for painted canvases. The etchings, of which there are only about a couple of dozen, are of the middle period of his practice; they show a diversity of method as well as of theme.

He made his Salon debut in 1861 with four paintings of kitchen subjects.[2] Collectors purchased the works, and his paintings in the Salons of 1864 and 1865 were awarded medals.

Ribot painted domestic genre works, still-lifes, portraits, as well as religious scenes, such as his Salon success St. Sebastian, Martyr (1865). The earlier work was drier and austere but still with an intensity of conception and presentation; later works were freer and broader. His preference was for painting directly from nature, emphasizing the contrasts of light and dark. His use of chiaroscuro to suggest psychological states grew from his admiration for Spanish and Dutch baroque masters such as Ribera and Rembrandt, an enthusiasm shared by his contemporaries Courbet and Bonvin. Members of Ribot's family are the likely models for many of his figure compositions, in which the subjects engage in humble activities, such as preparing meals or gathering in groups to read to each other. The light draws attention to faces and hands, which emerge sharply from dimly lit surroundings.

Although the realism of Ribot's work aligns him with the most progressive artists of the generation preceding the Impressionists, he was no revolutionary, and his work met with a generally favorable response from the public and from critics.

In 1878 Ribot received the Légion d'honneur. At about this time, in ill health, he stopped painting and moved to Colombes, where he died in 1891.