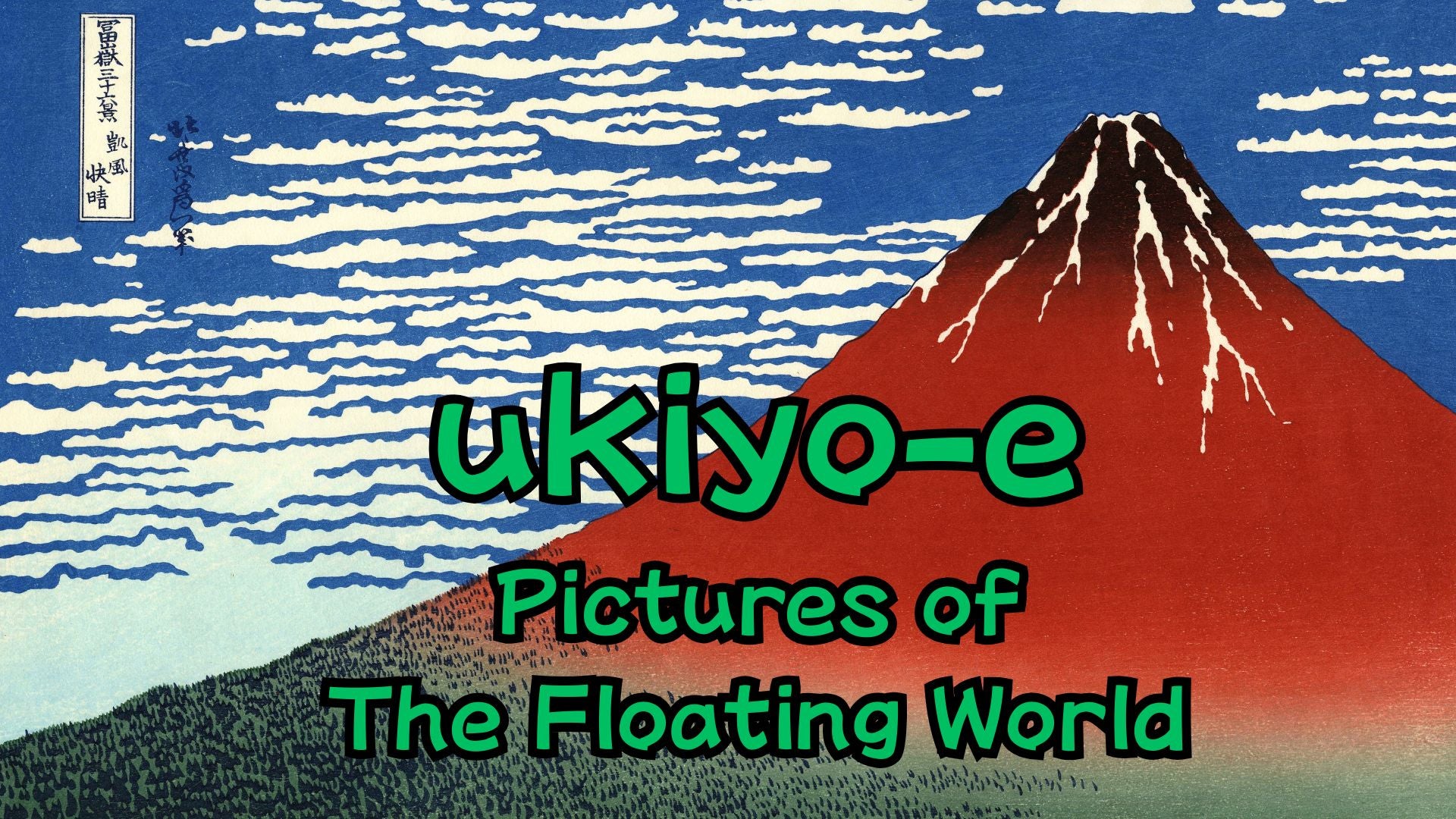

Ukiyo-e, which translates to "pictures of the floating world," is a genre of Japanese art that flourished during the Edo period (1603-1868). This artistic movement captured the essence of everyday life in Japan, focusing on the fleeting pleasures and ephemeral nature of the world. Ukiyo-e not only left an indelible mark on Japanese culture but also significantly influenced Western art, particularly the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movements.

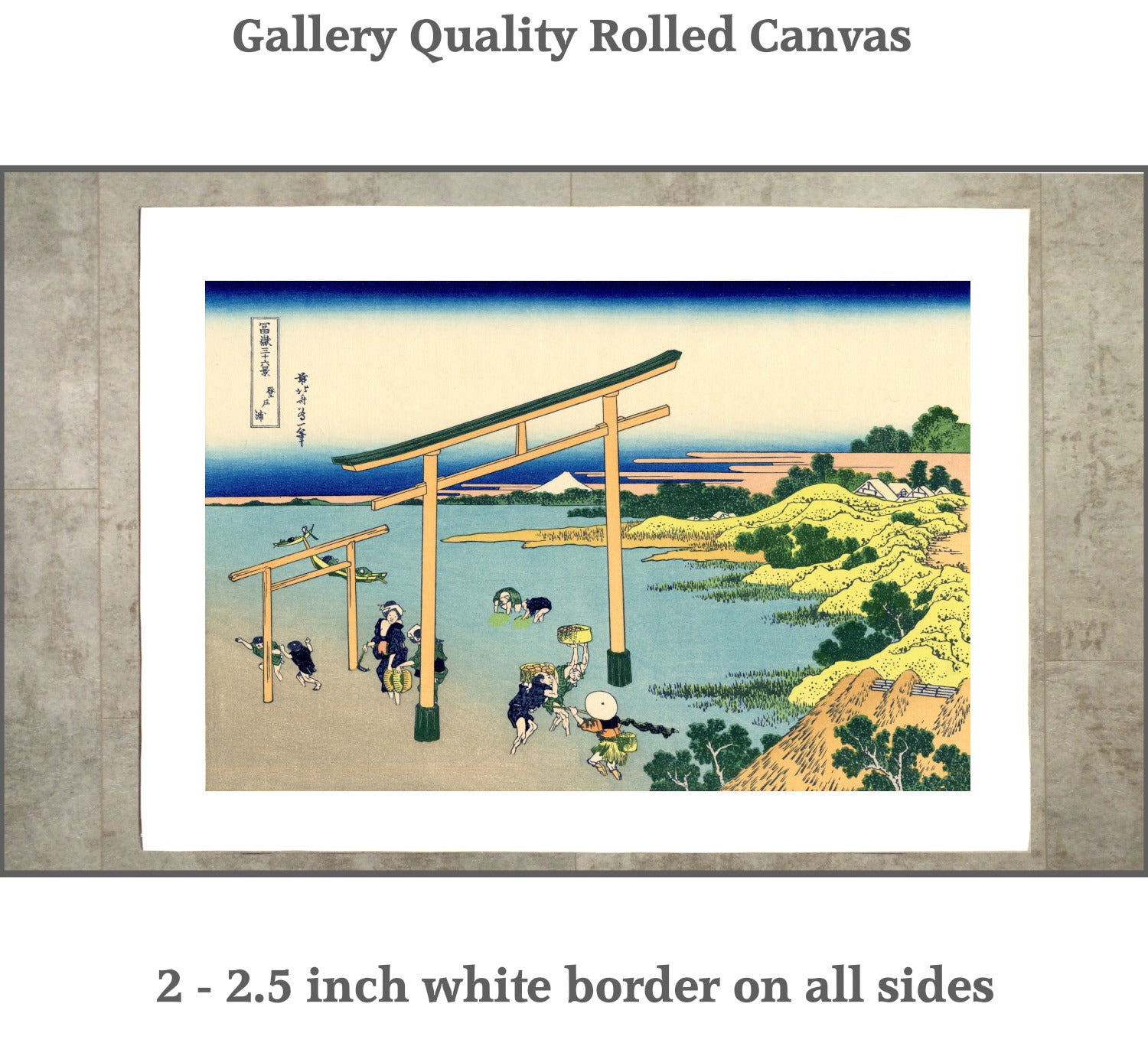

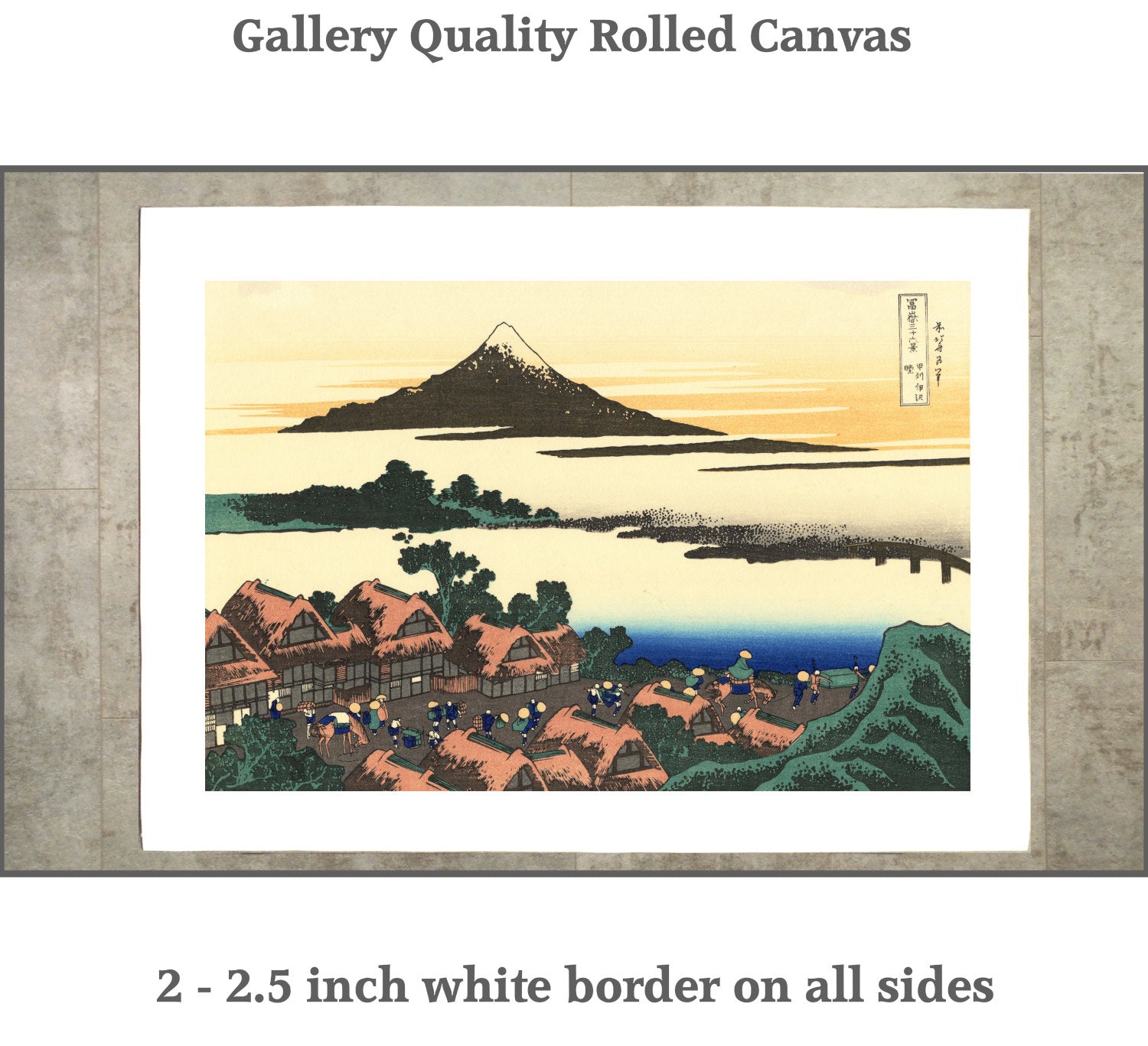

Red Fuji, Southern Wind Clear Morning, Katsushika Hokusai

Origins and Development

The term "ukiyo" originally had Buddhist connotations, referring to the transient nature of human life. However, during the Edo period, its meaning shifted to describe the hedonistic lifestyle of the urban population, particularly in Edo (modern-day Tokyo). The art form emerged as a way to depict and celebrate this new urban culture, with its focus on entertainment, beauty, and sensual pleasures.

Ukiyo-e began as black and white illustrations in books and eventually evolved into single-sheet prints and paintings. The development of woodblock printing techniques in the 18th century allowed for mass production, making these artworks accessible to a broader audience. This democratization of art was revolutionary, as it allowed common people to own and enjoy beautiful artworks that were previously reserved for the elite.

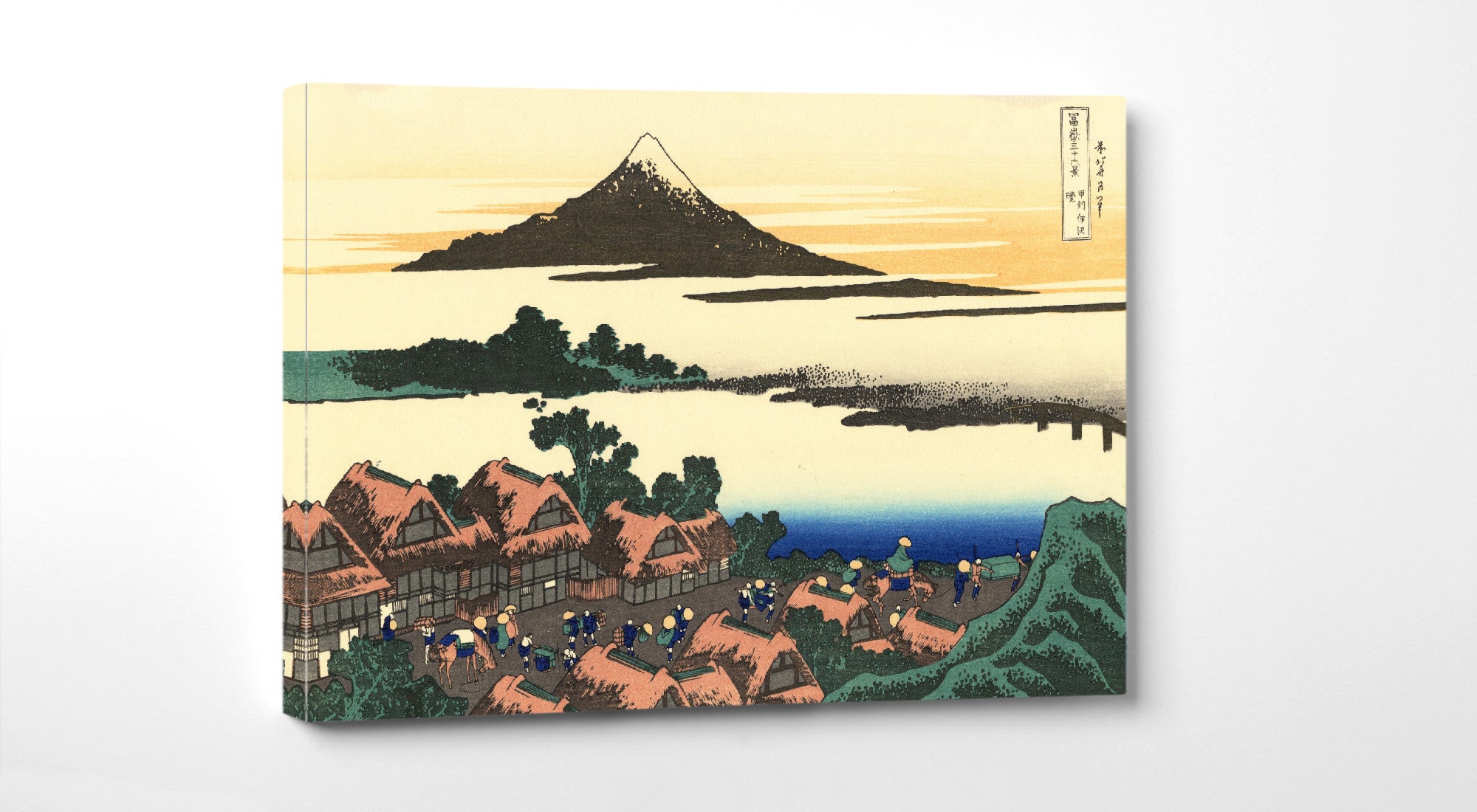

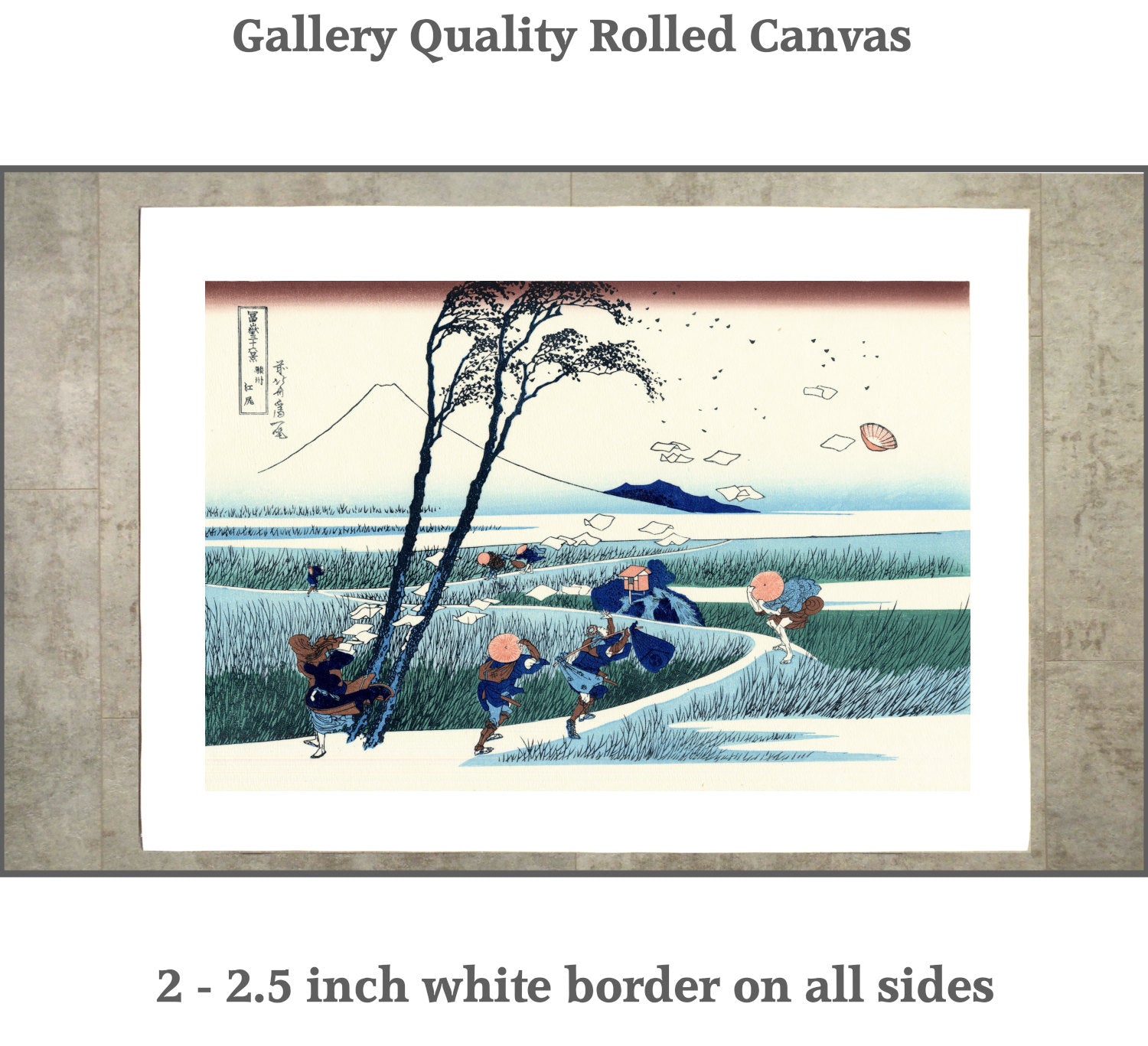

Andō Hiroshige, 53 Stations Tokaido : Sakashita

Themes and Subjects

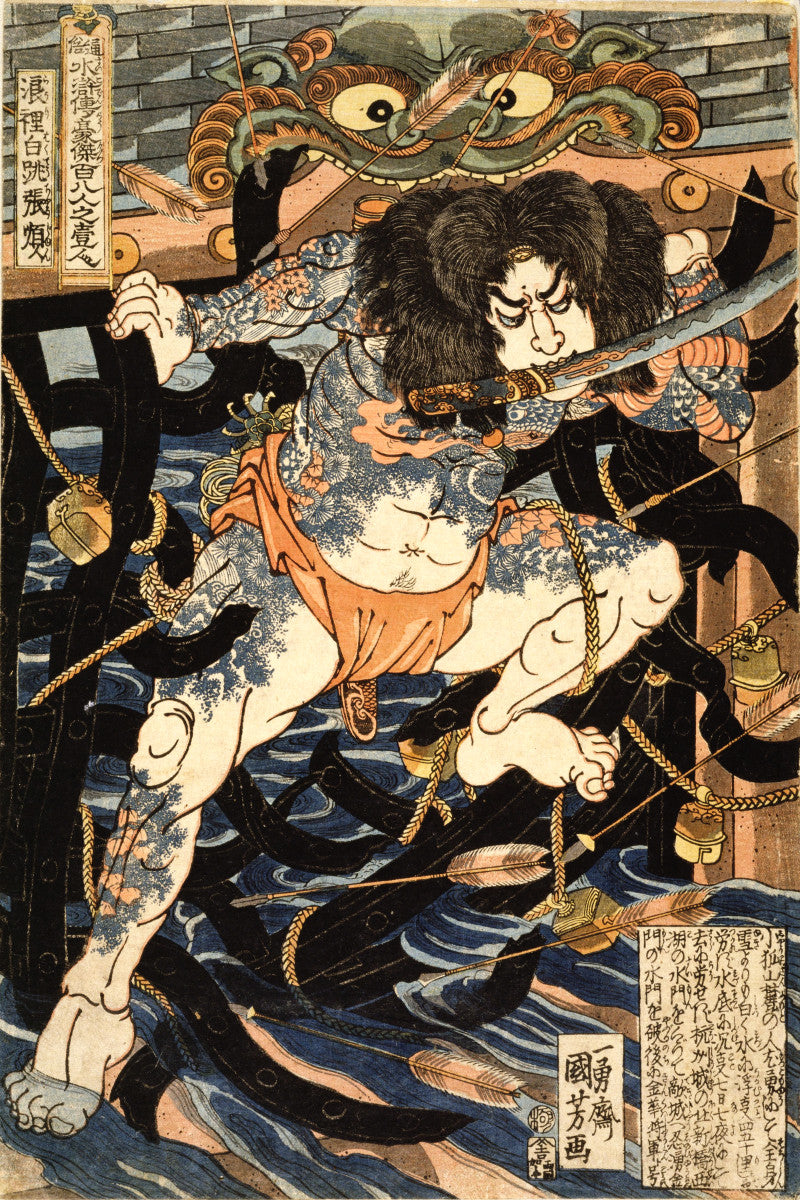

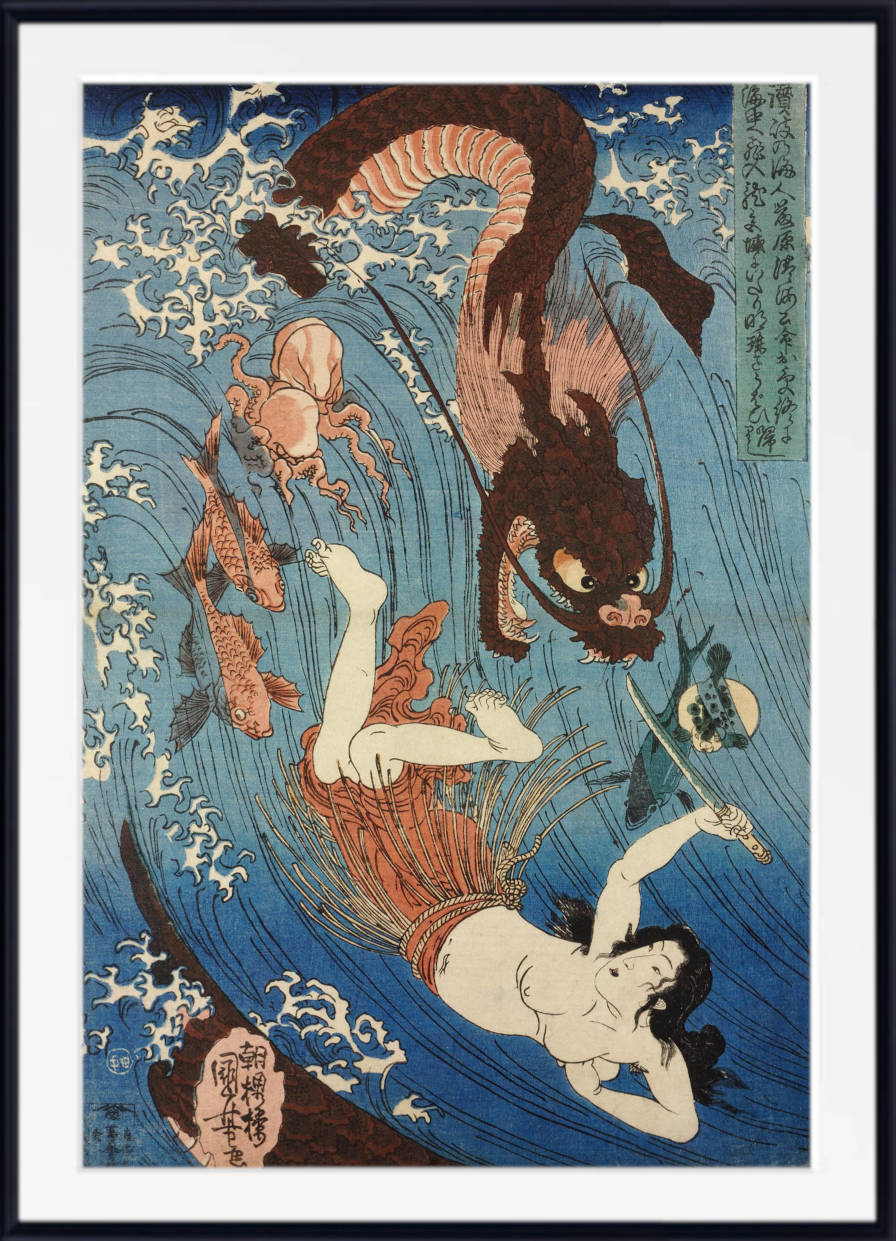

Ukiyo-e artists drew inspiration from various aspects of everyday life in Edo-period Japan. Some of the most popular themes included:

- Bijin-ga: Portraits of beautiful women, including geisha and courtesans.

- Yakusha-e: Depictions of Kabuki theater actors in dramatic poses or scenes from plays.

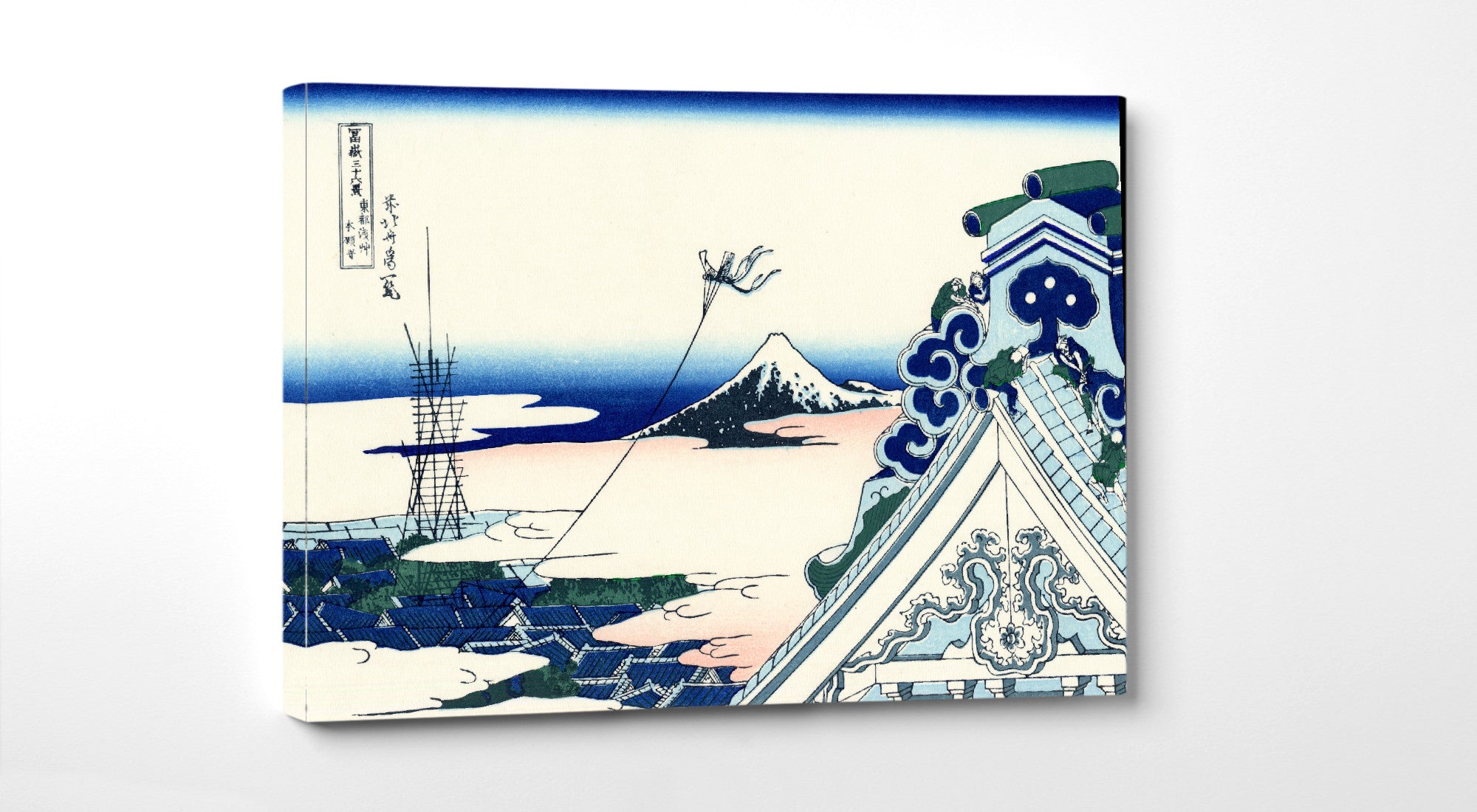

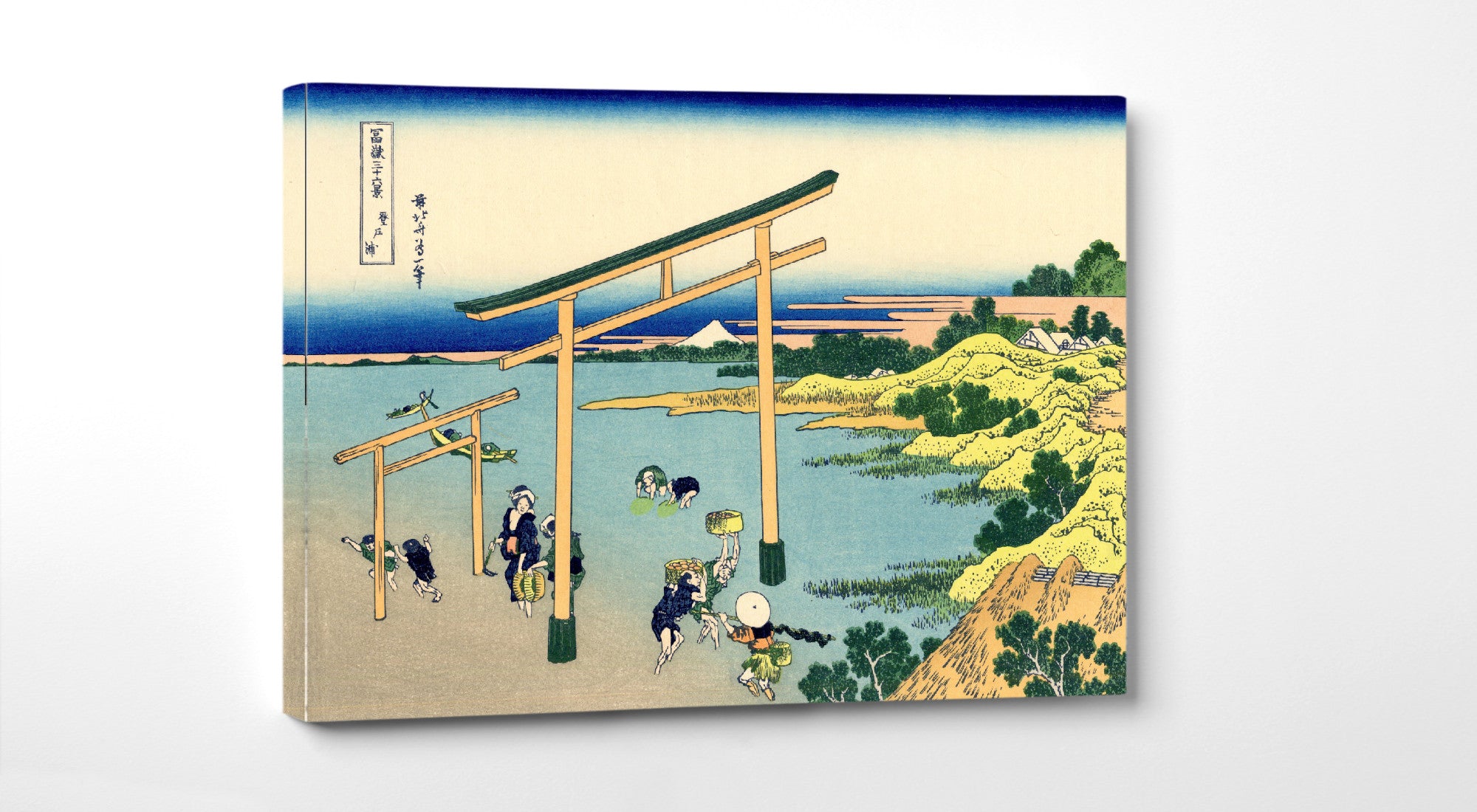

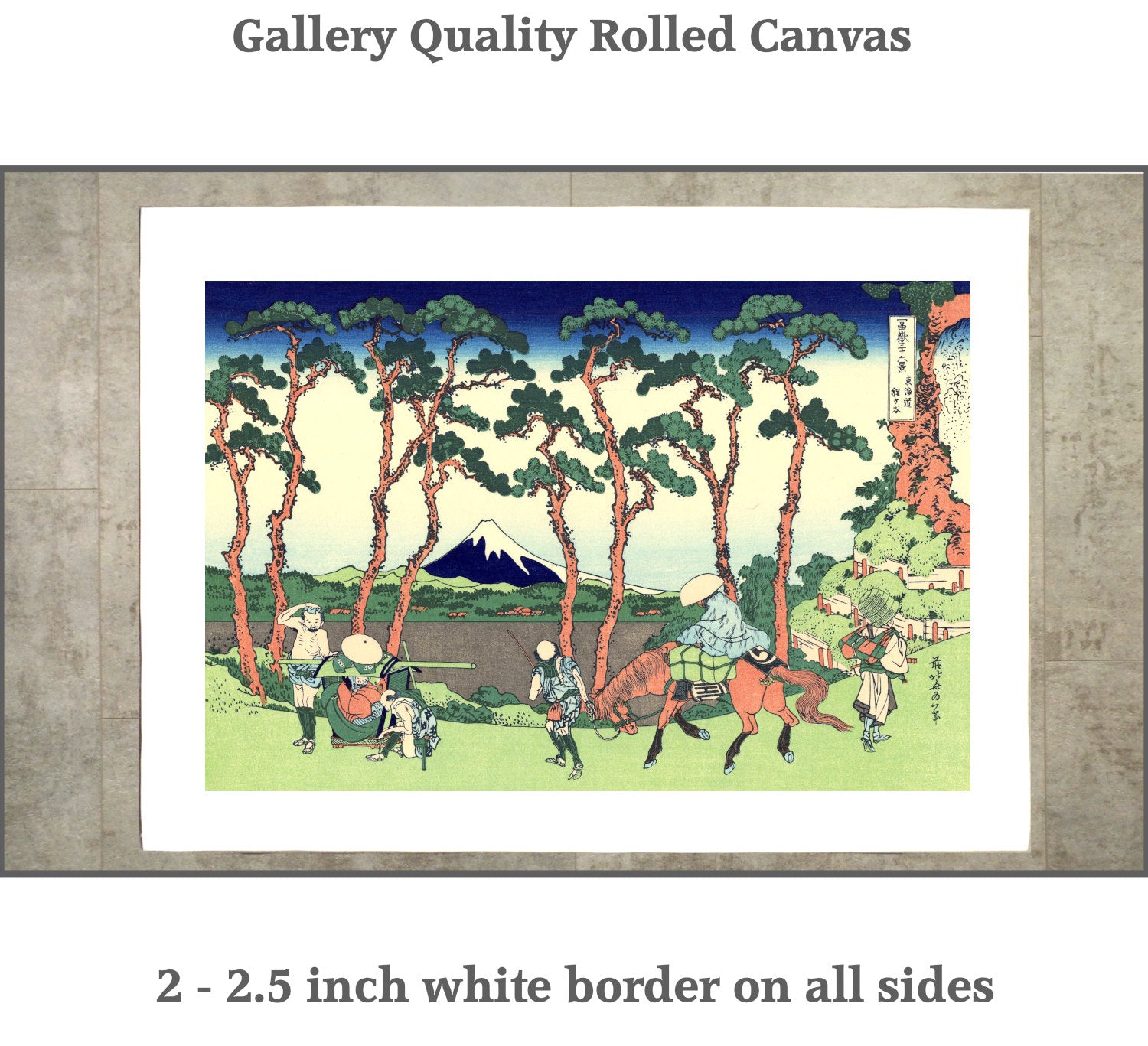

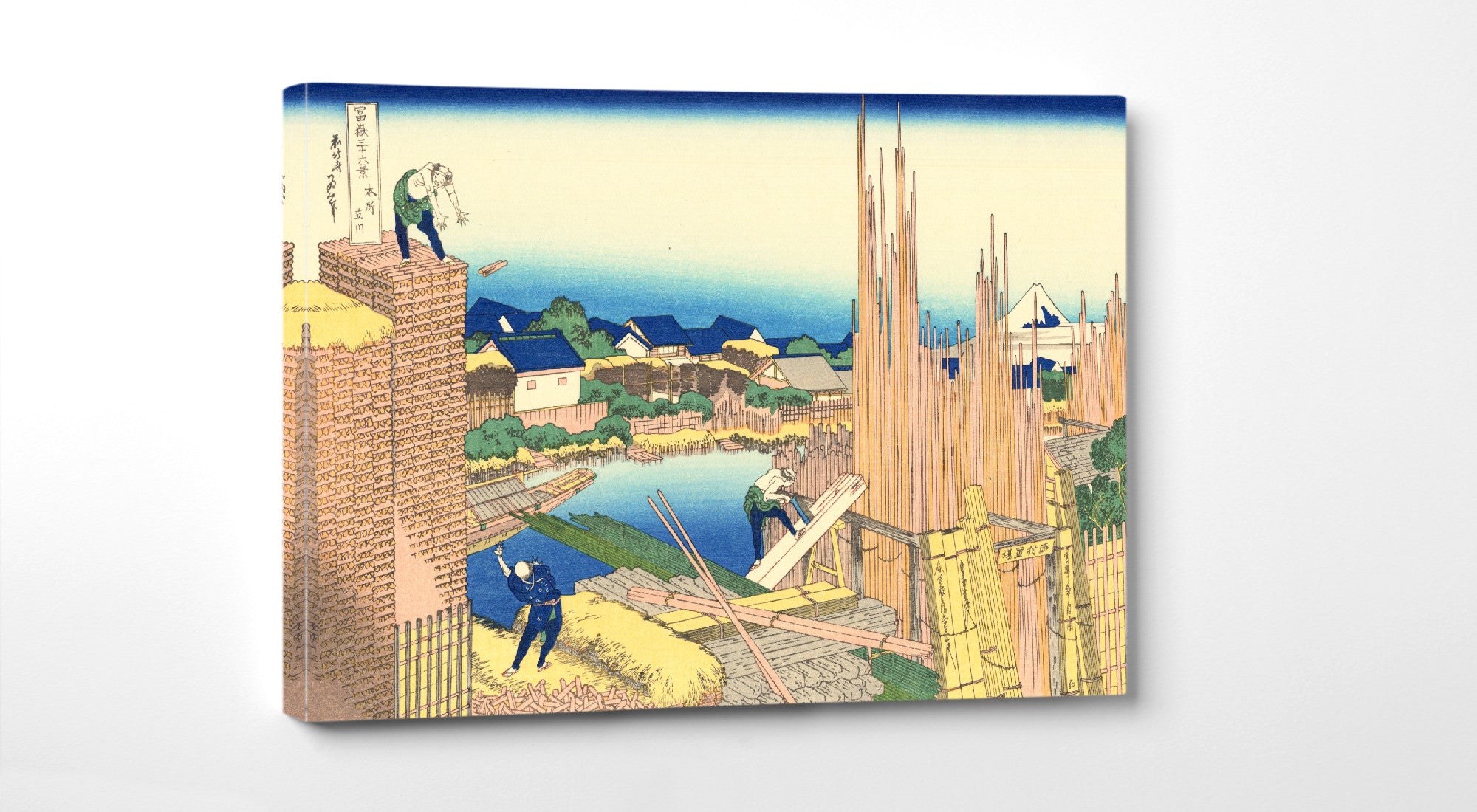

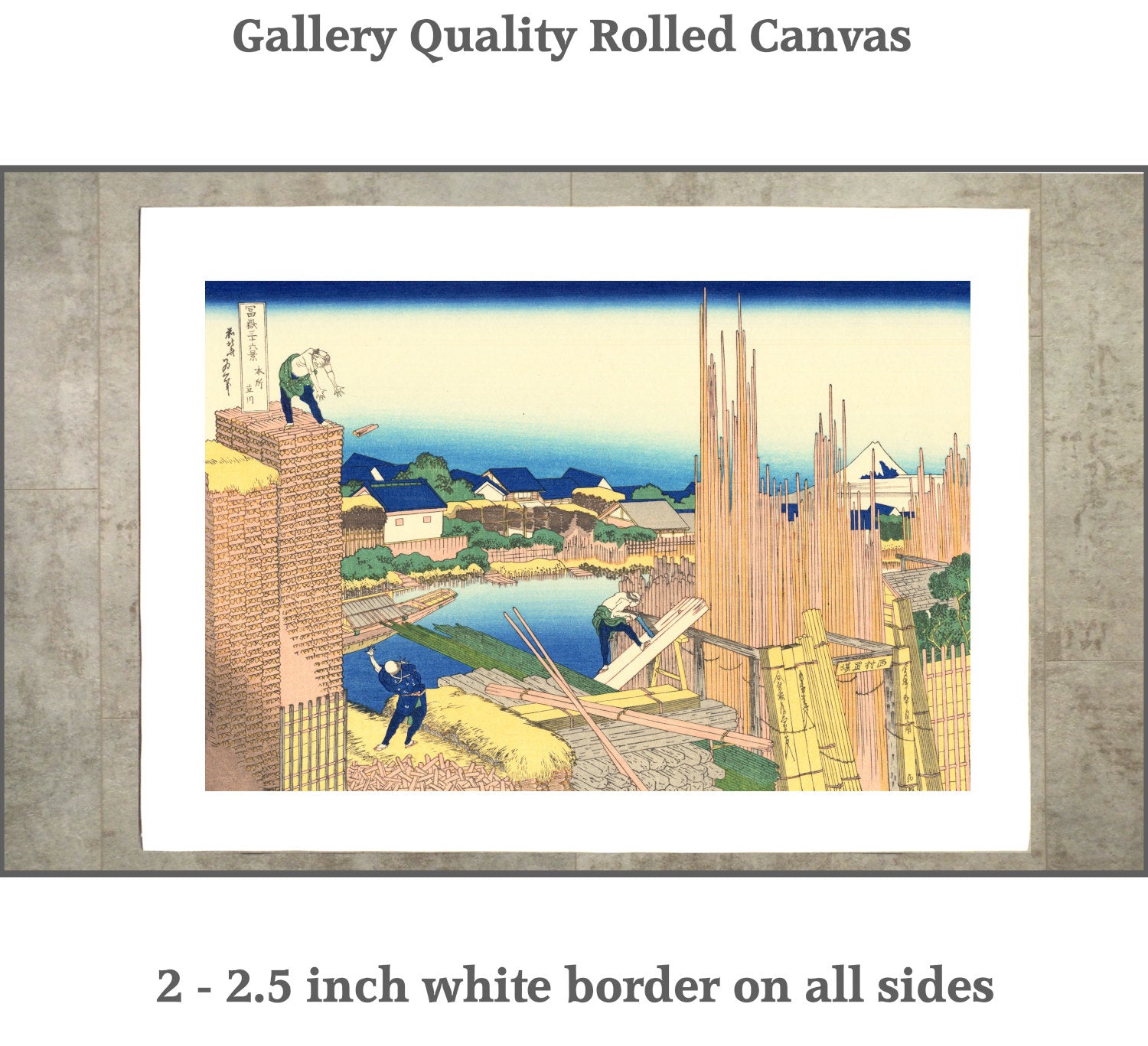

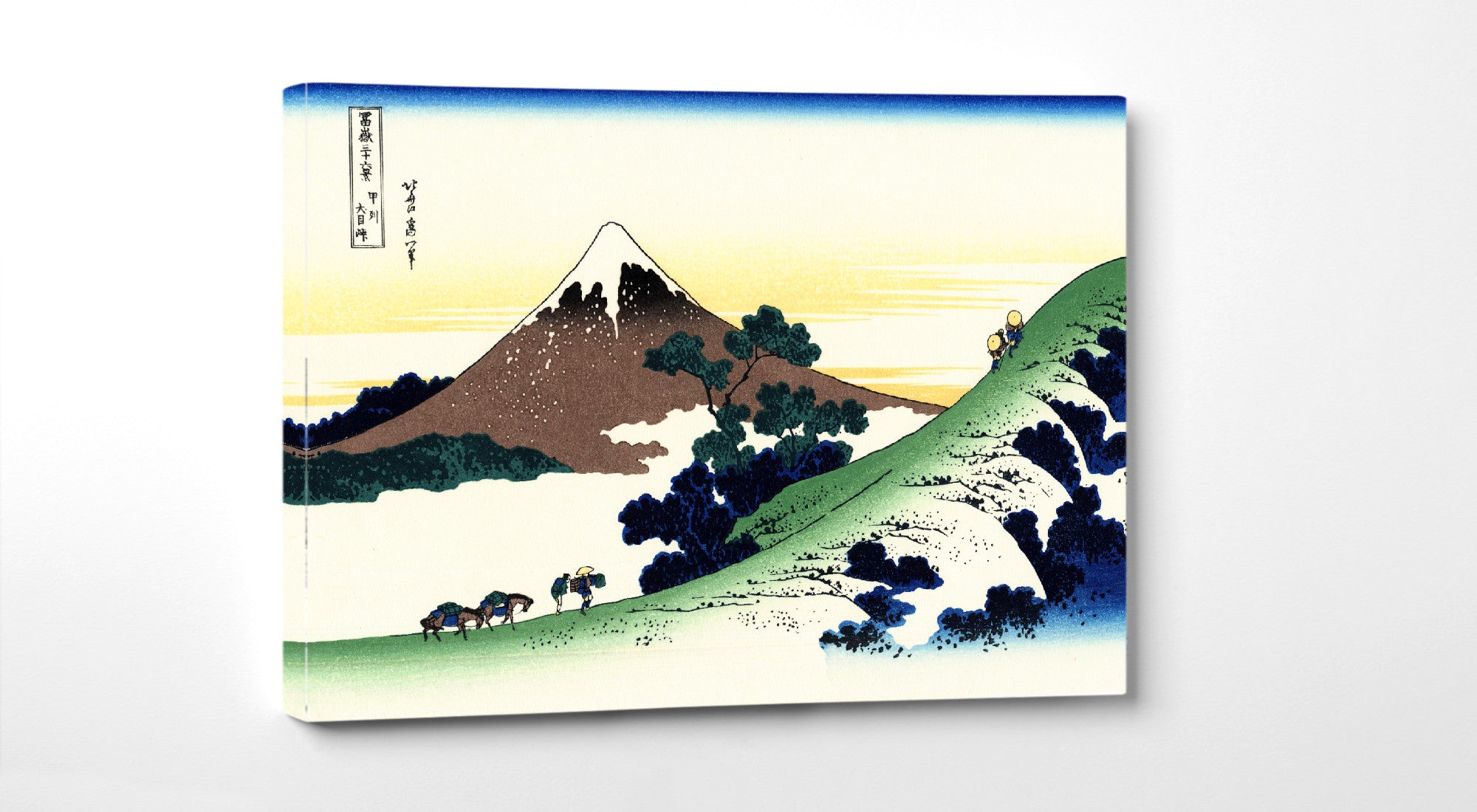

- Landscapes: Famous locations, natural scenery, and travel scenes.

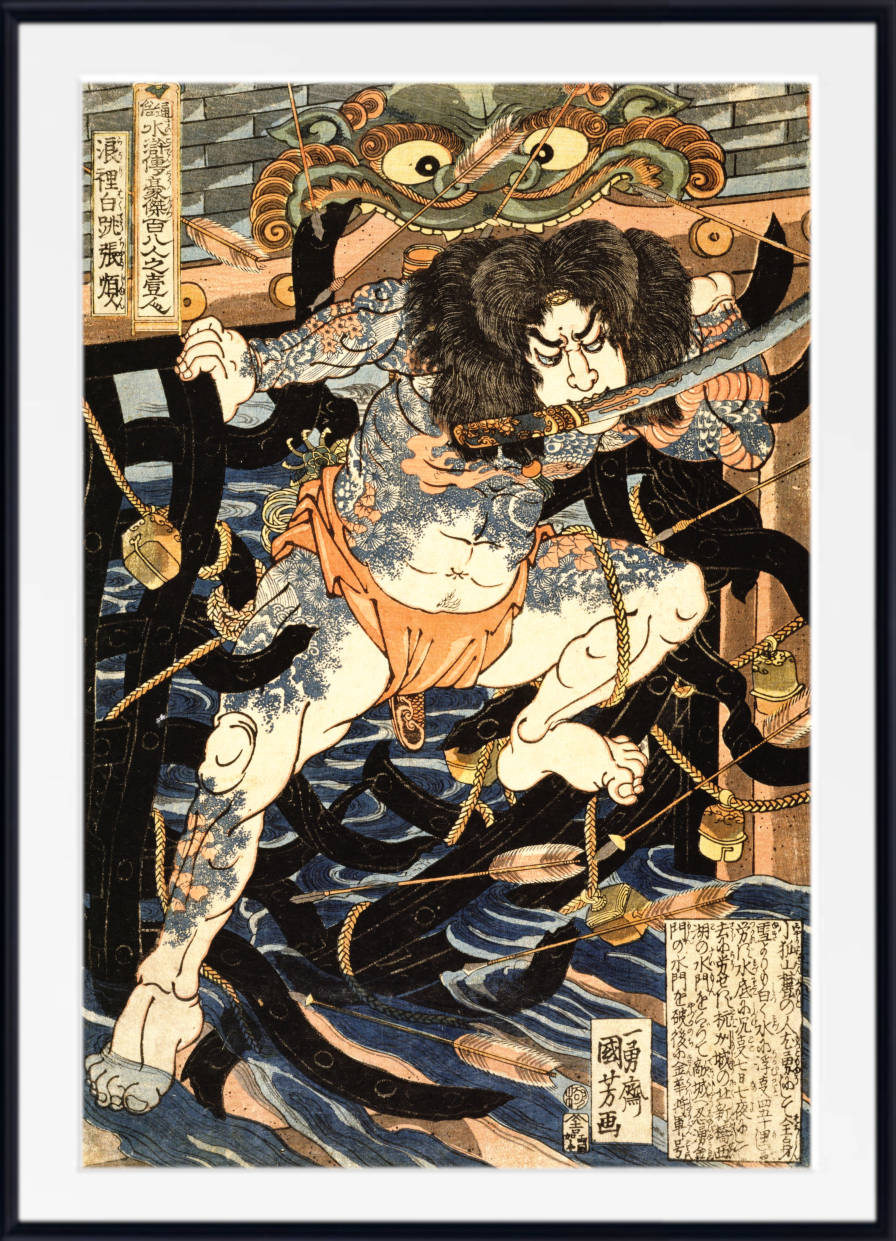

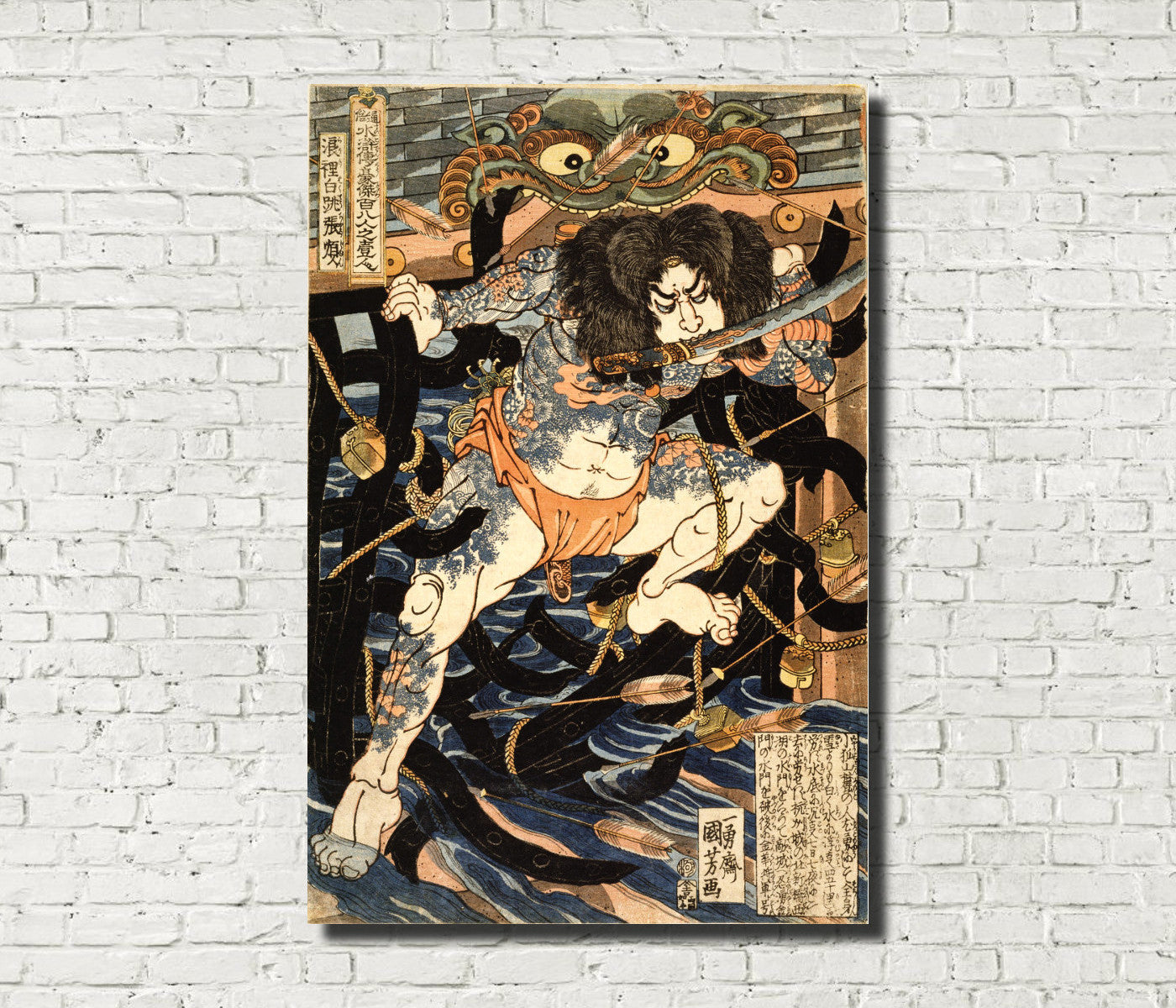

- Historical and mythological subjects: Scenes from Japanese folklore, legends, and historical events.

- Sumo wrestlers: Portraits and action scenes of this popular sport.

- Nature studies: Detailed depictions of flowers, birds, and other natural subjects.

These themes reflected the interests and values of the urban population during the Edo period, providing a window into the cultural life of the time.

Kawanabe Kyōsai, Pheasant Caught by a Snake

Techniques and Production

The creation of ukiyo-e prints involved a collaborative process between several artisans:

- The artist (e-shi) who designed the image

- The block carver (hori-shi) who transferred the design onto wooden blocks

- The printer (suri-shi) who applied ink to the blocks and pressed them onto paper

This division of labor allowed for efficient production and specialization of skills. The process typically began with the artist creating a design on thin paper. This design was then glued face-down onto a cherry wood block and carved in relief, creating a separate block for each color in the final print. The printer would then apply ink to these blocks and press them onto handmade paper, building up layers of color to create the final image.

The use of multiple blocks for different colors was a significant innovation in ukiyo-e, allowing for the creation of complex, multi-colored prints. This technique, known as nishiki-e or "brocade pictures," became popular in the 1760s and contributed to the golden age of ukiyo-e in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Notable Artists

Several ukiyo-e artists achieved great fame and recognition for their work, both in Japan and internationally. Some of the most renowned include:

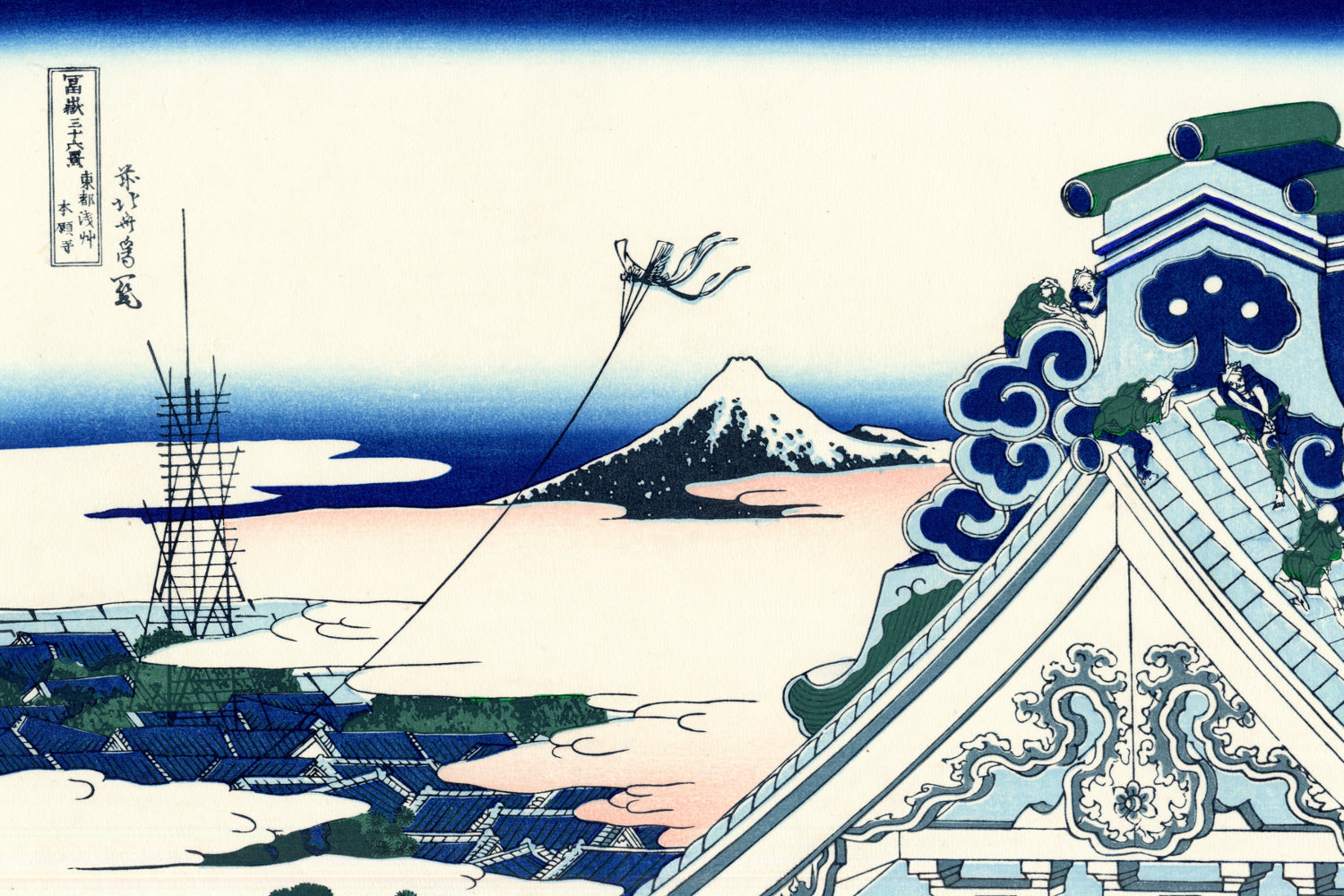

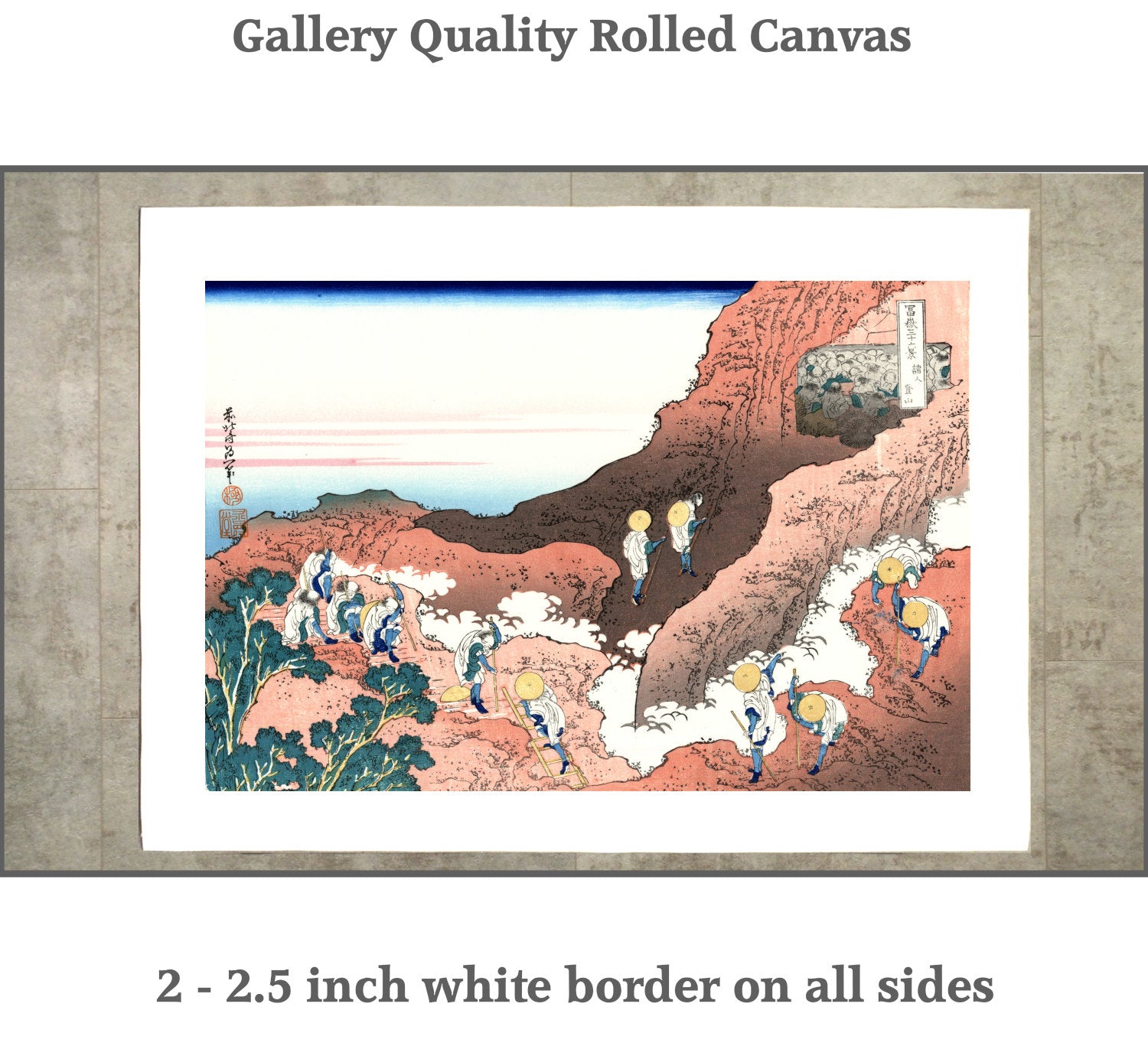

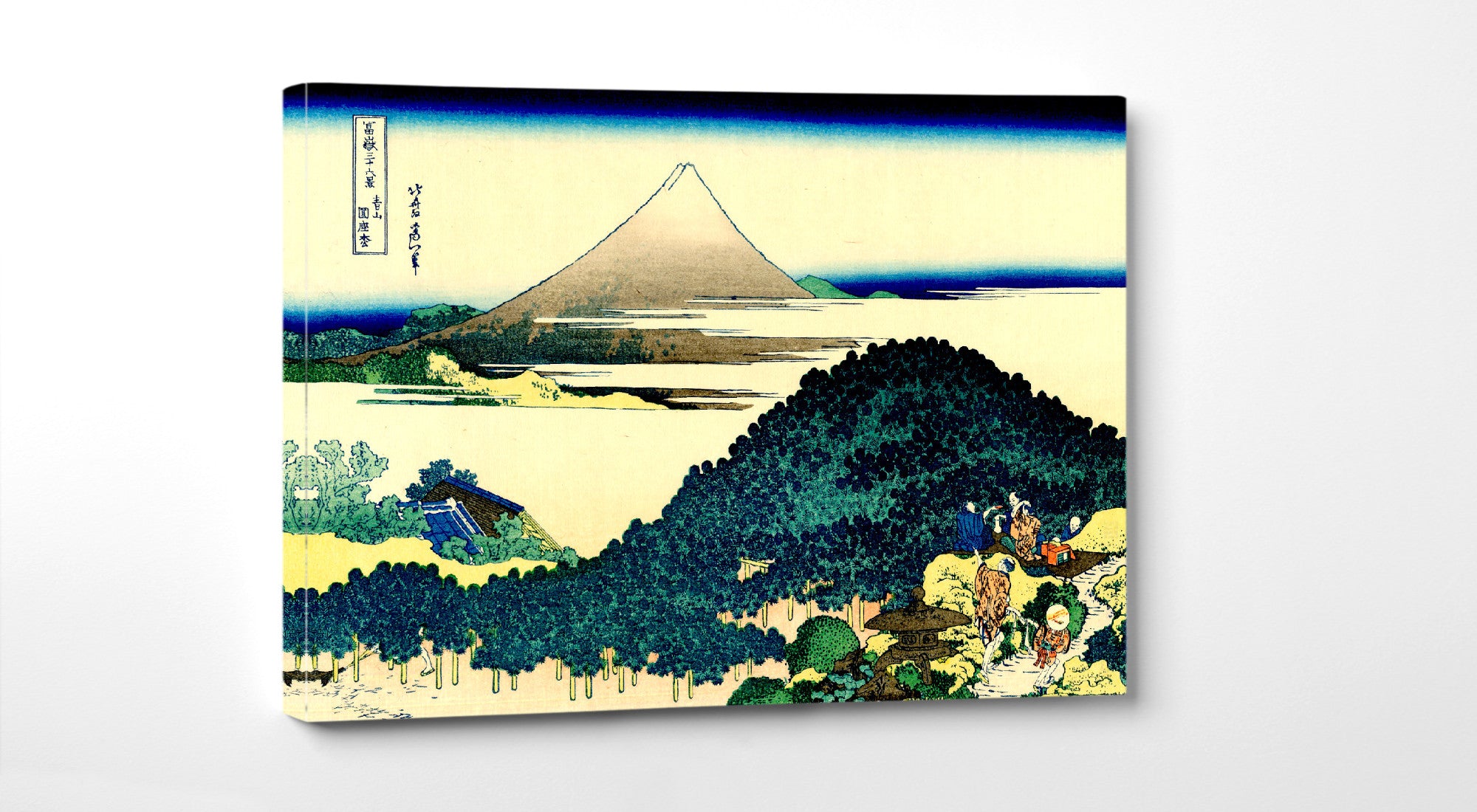

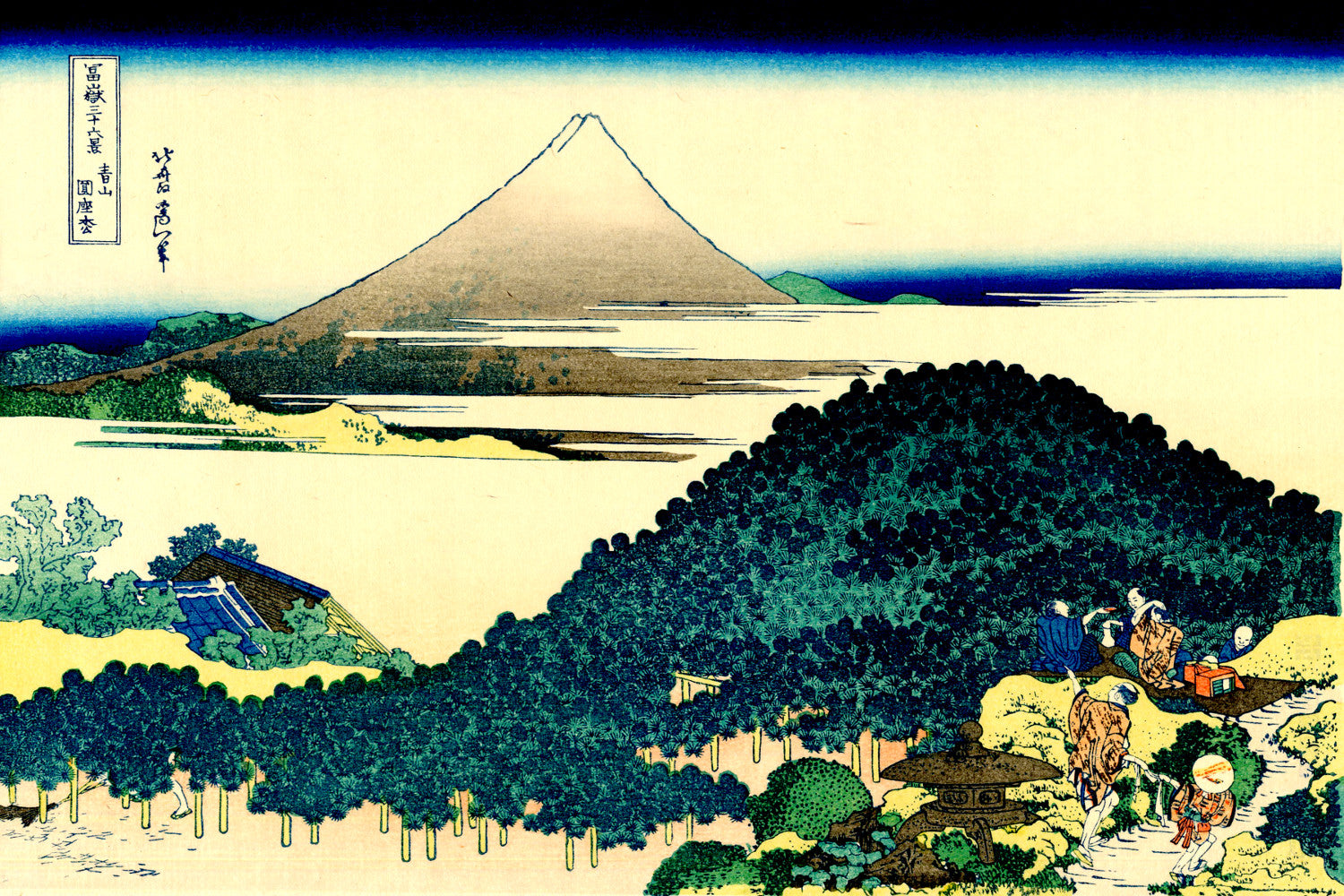

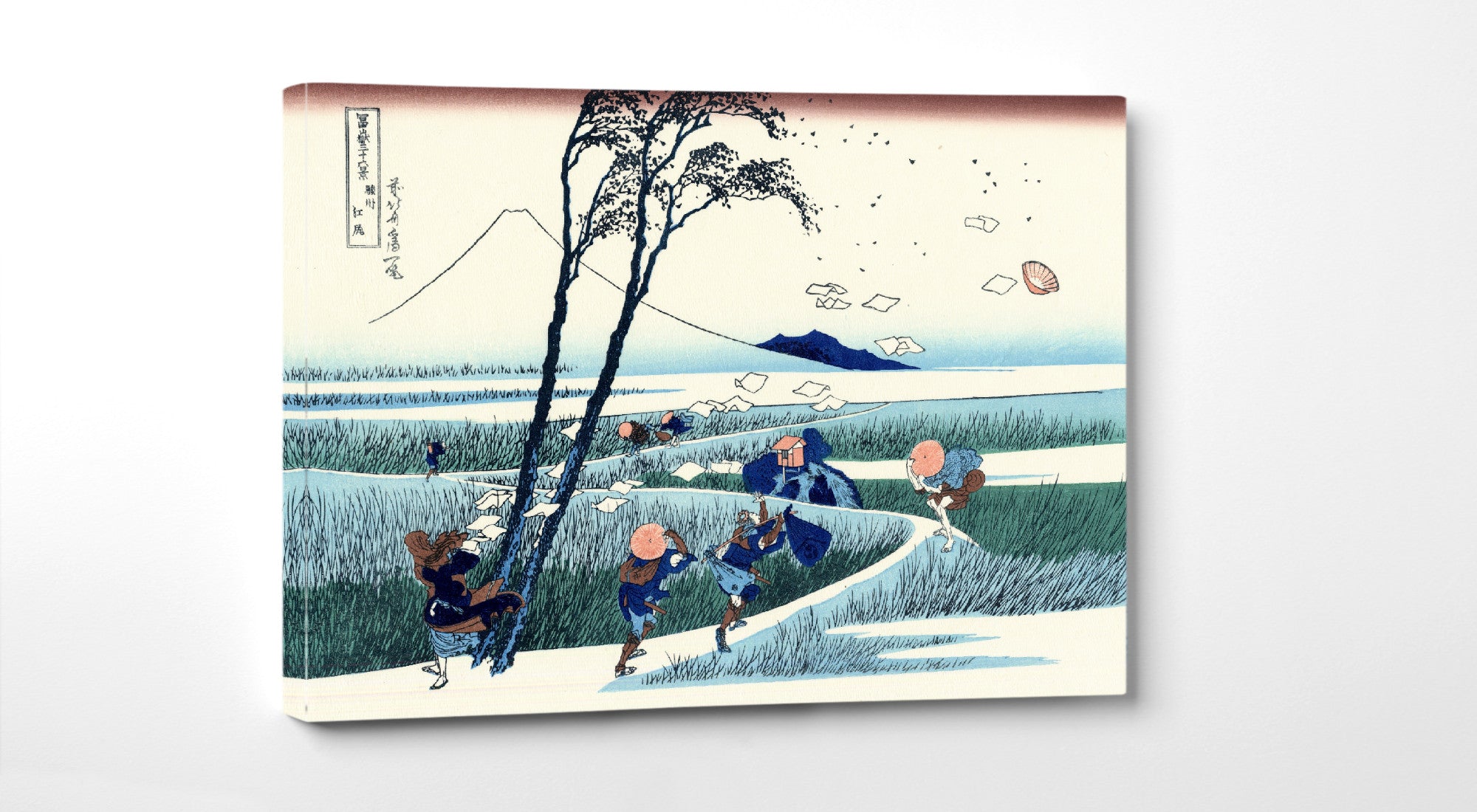

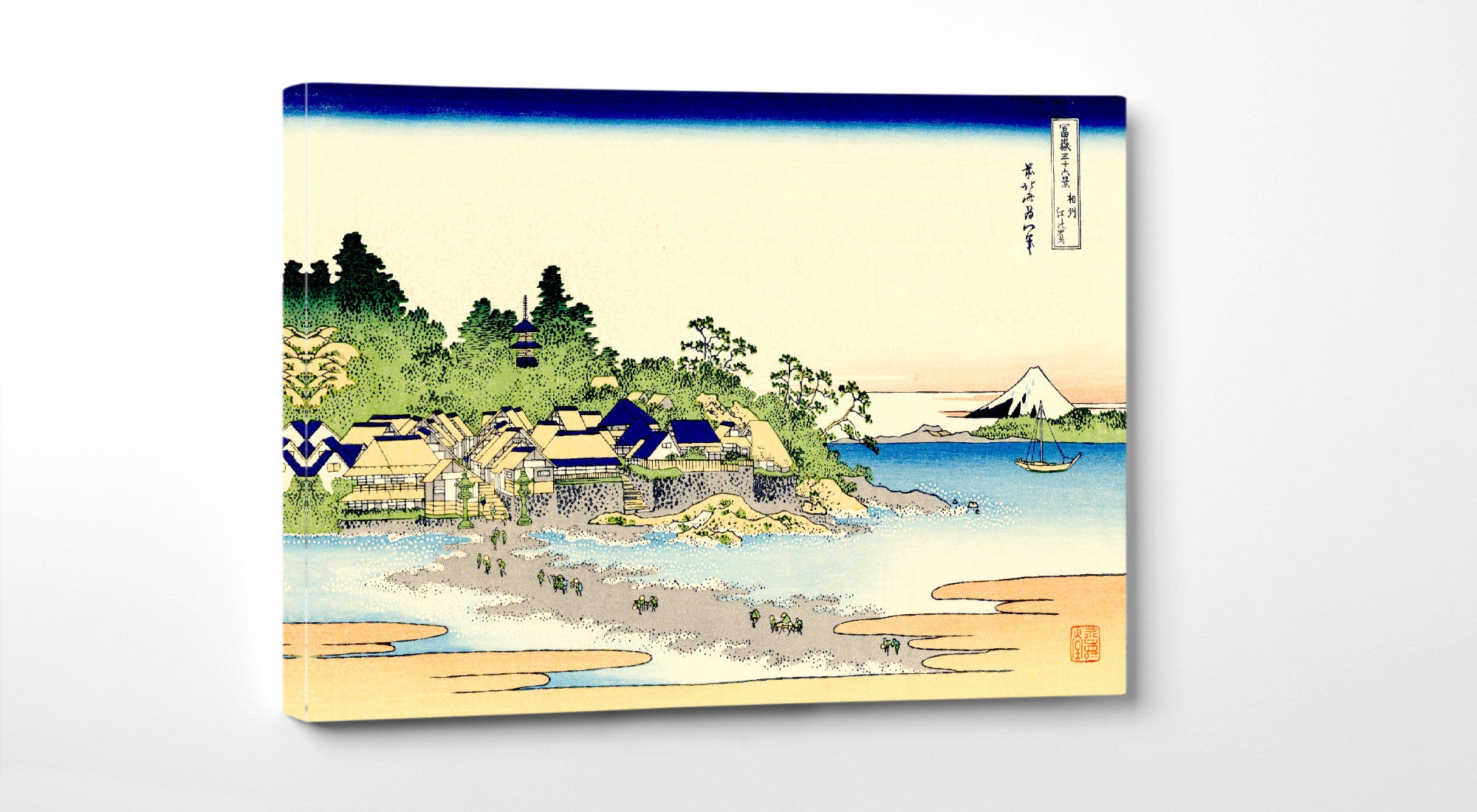

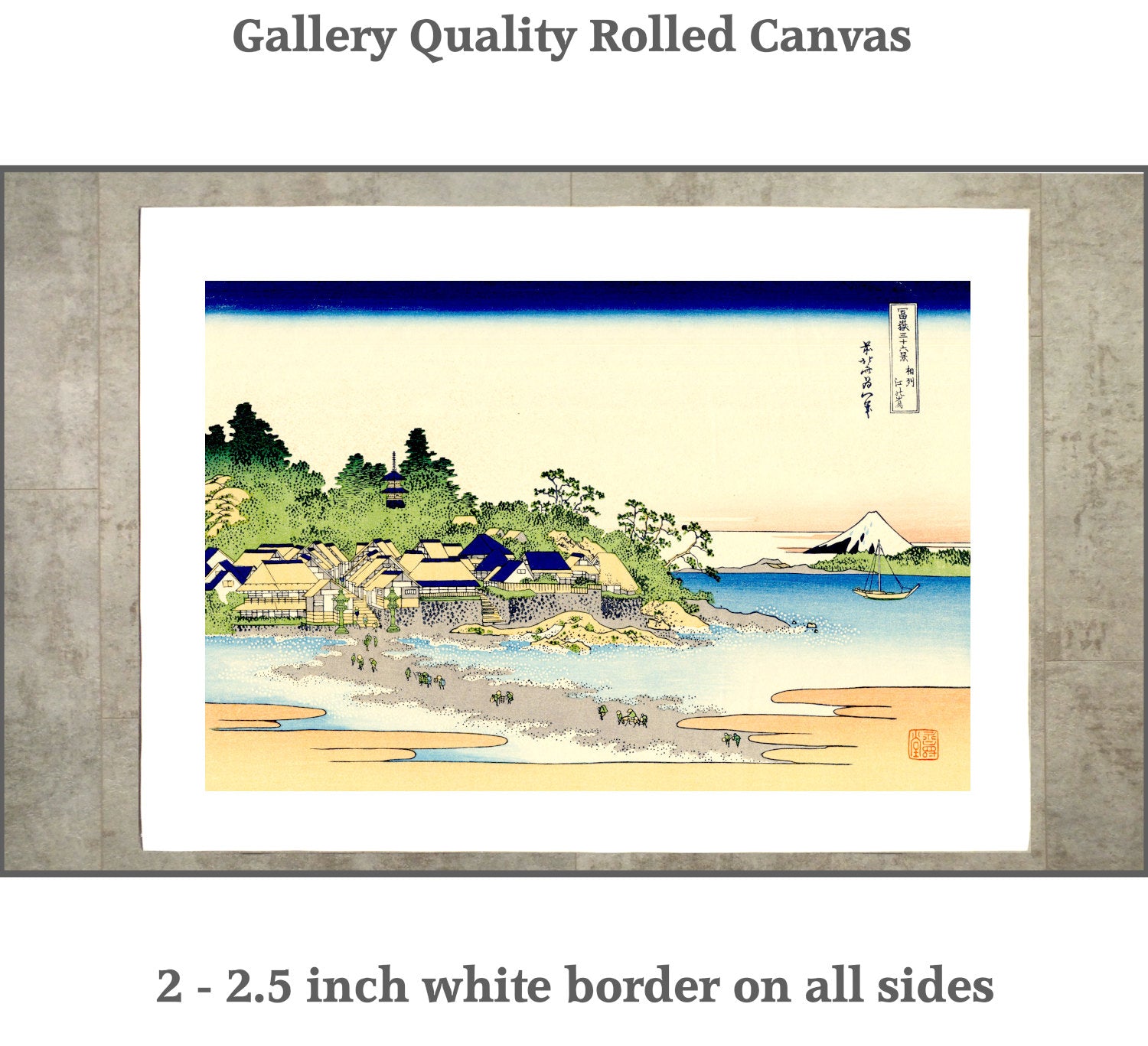

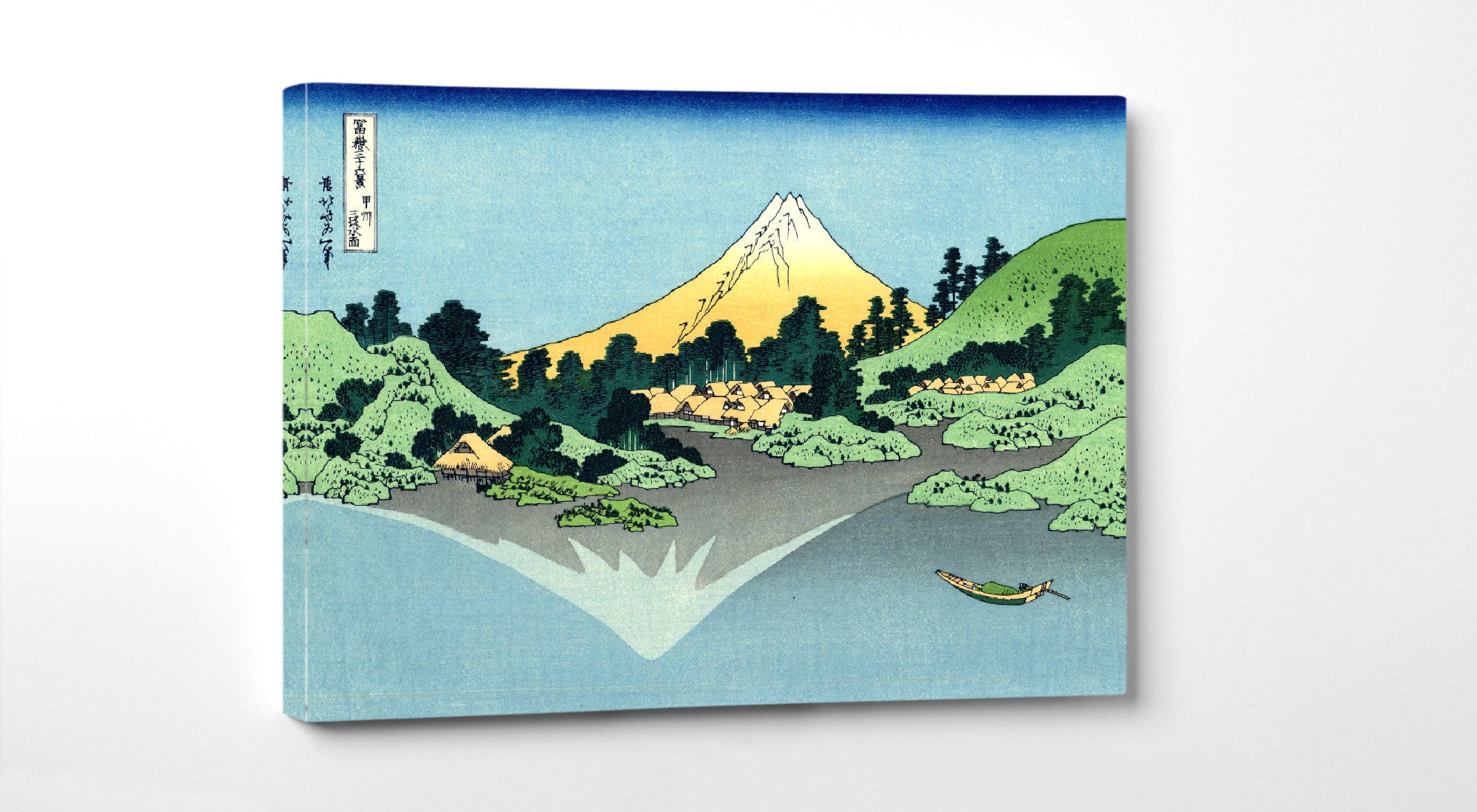

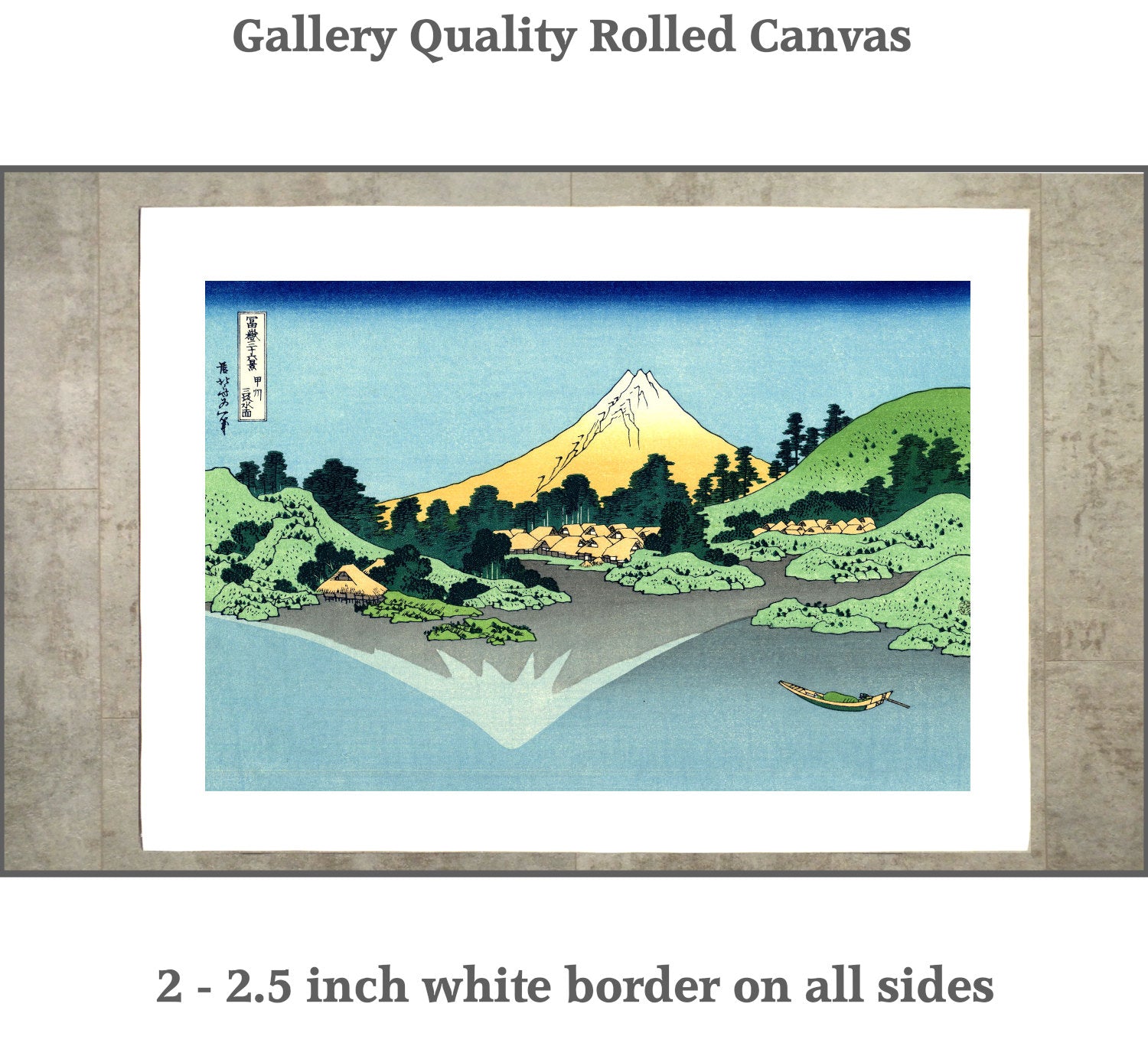

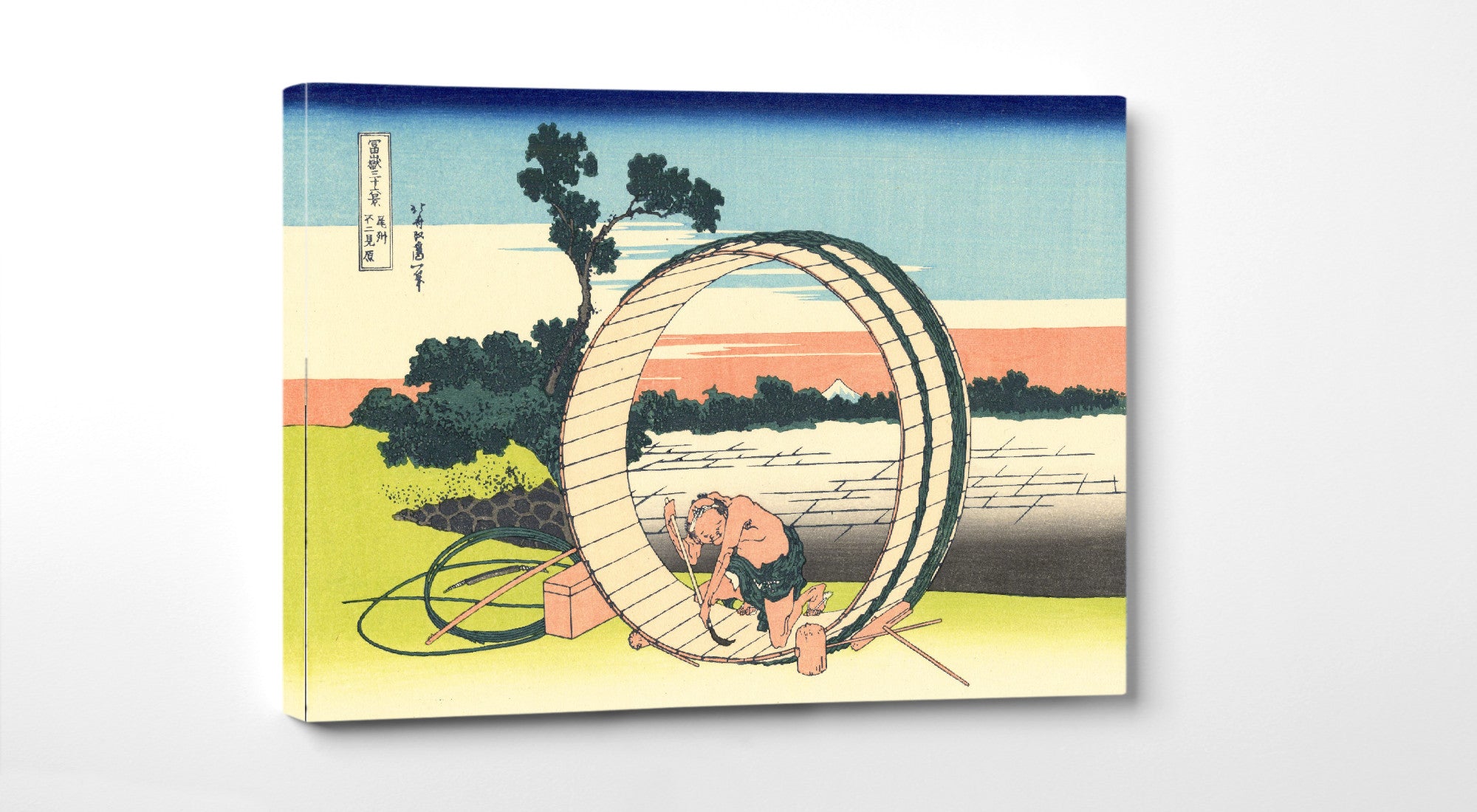

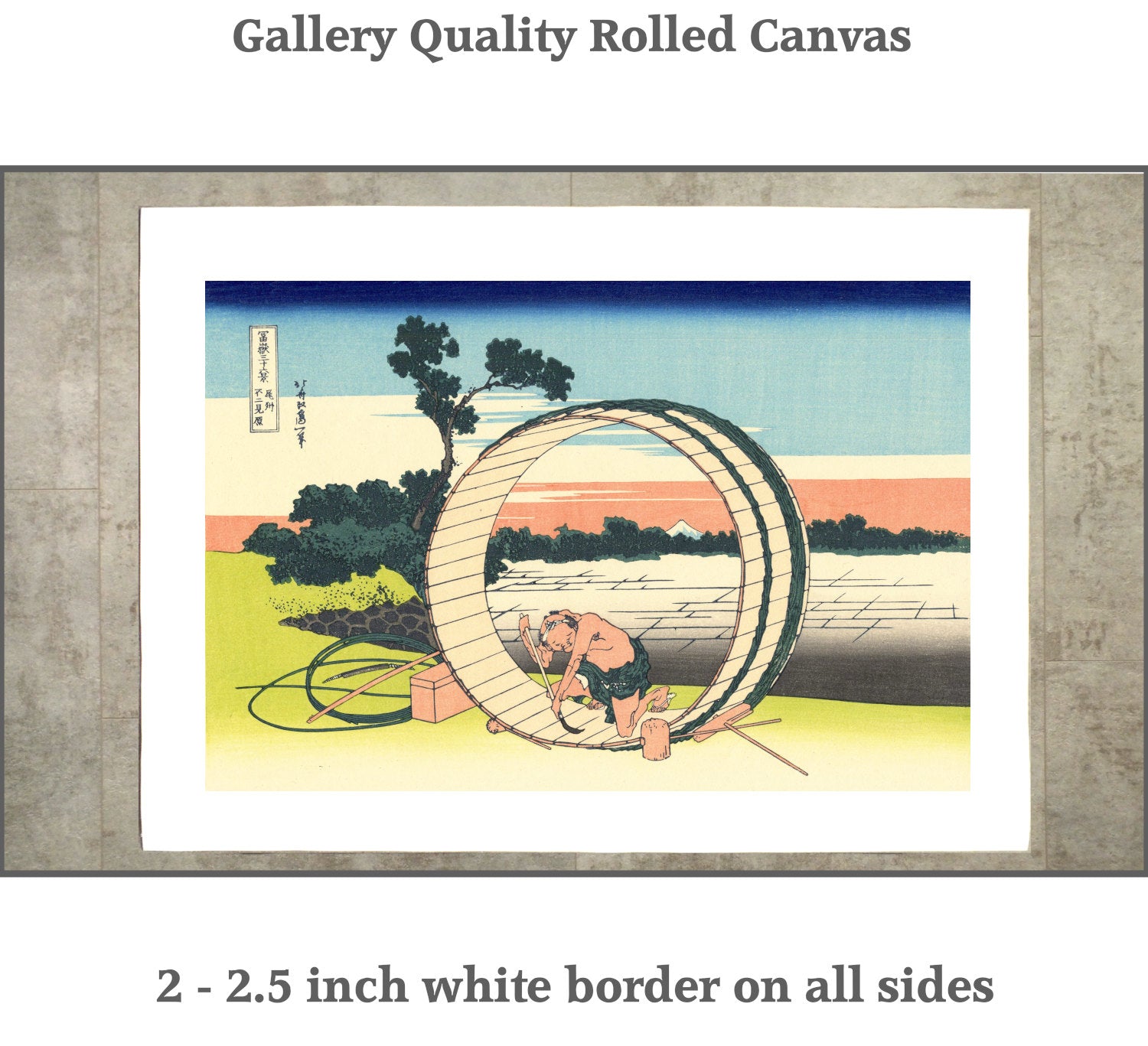

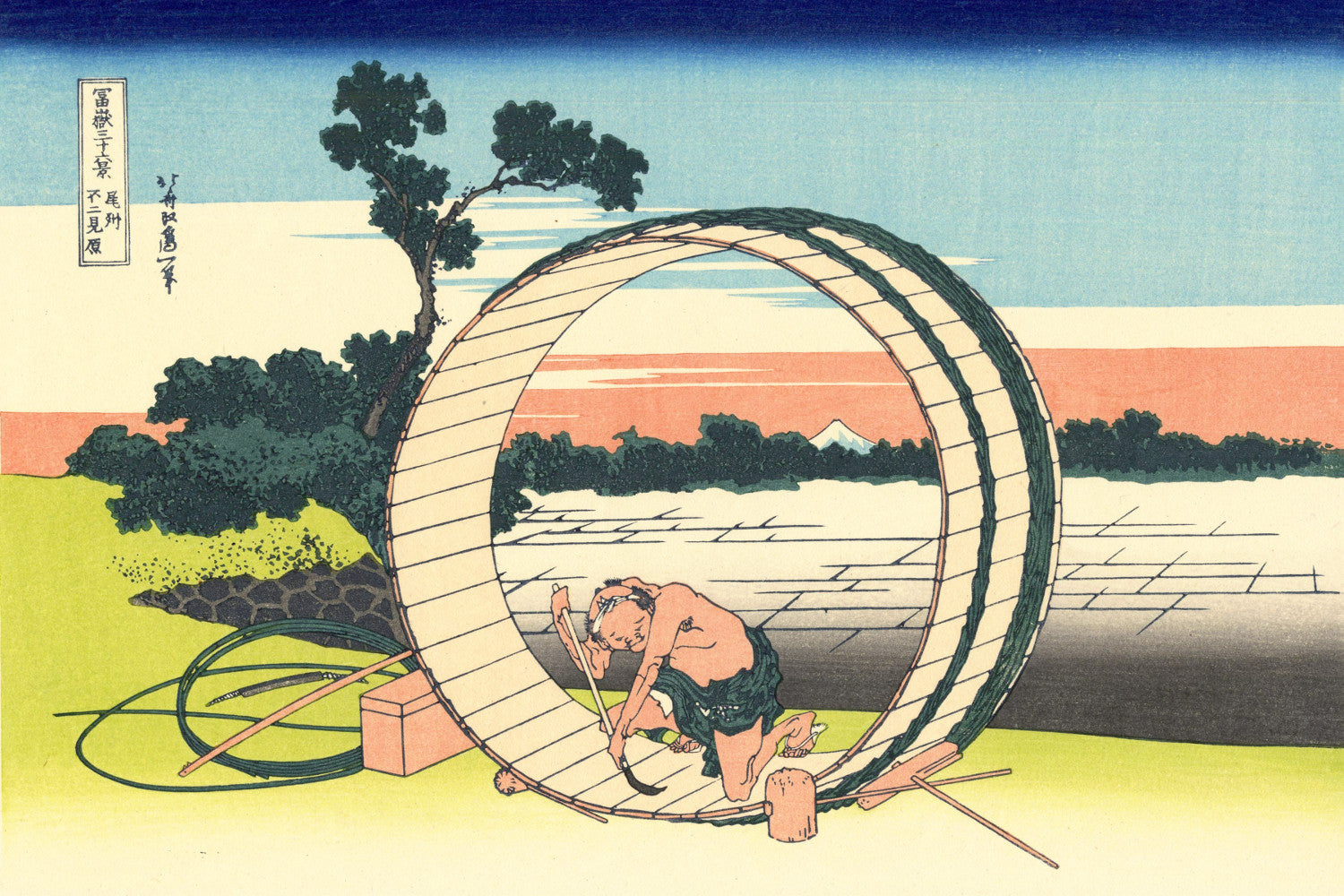

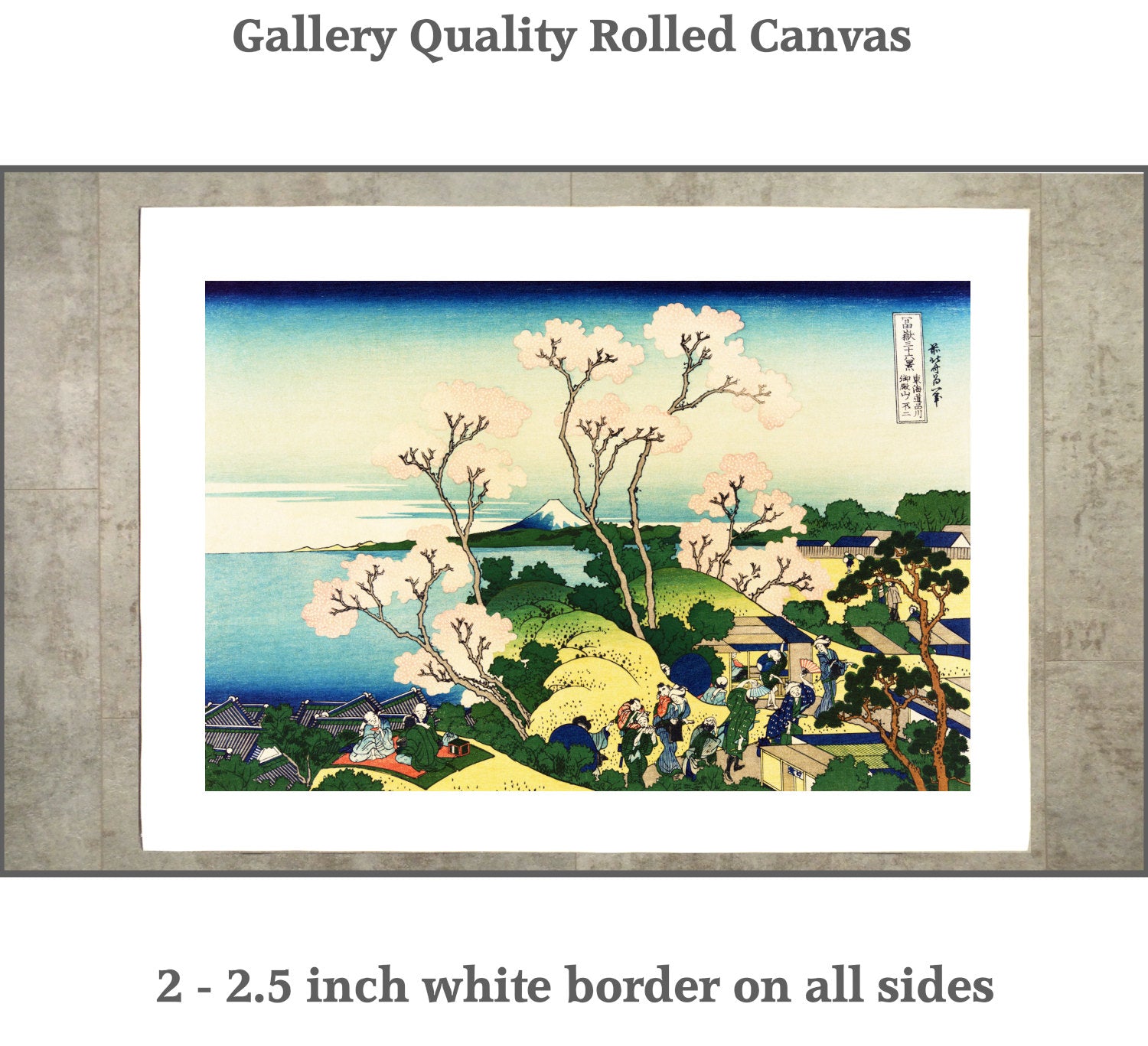

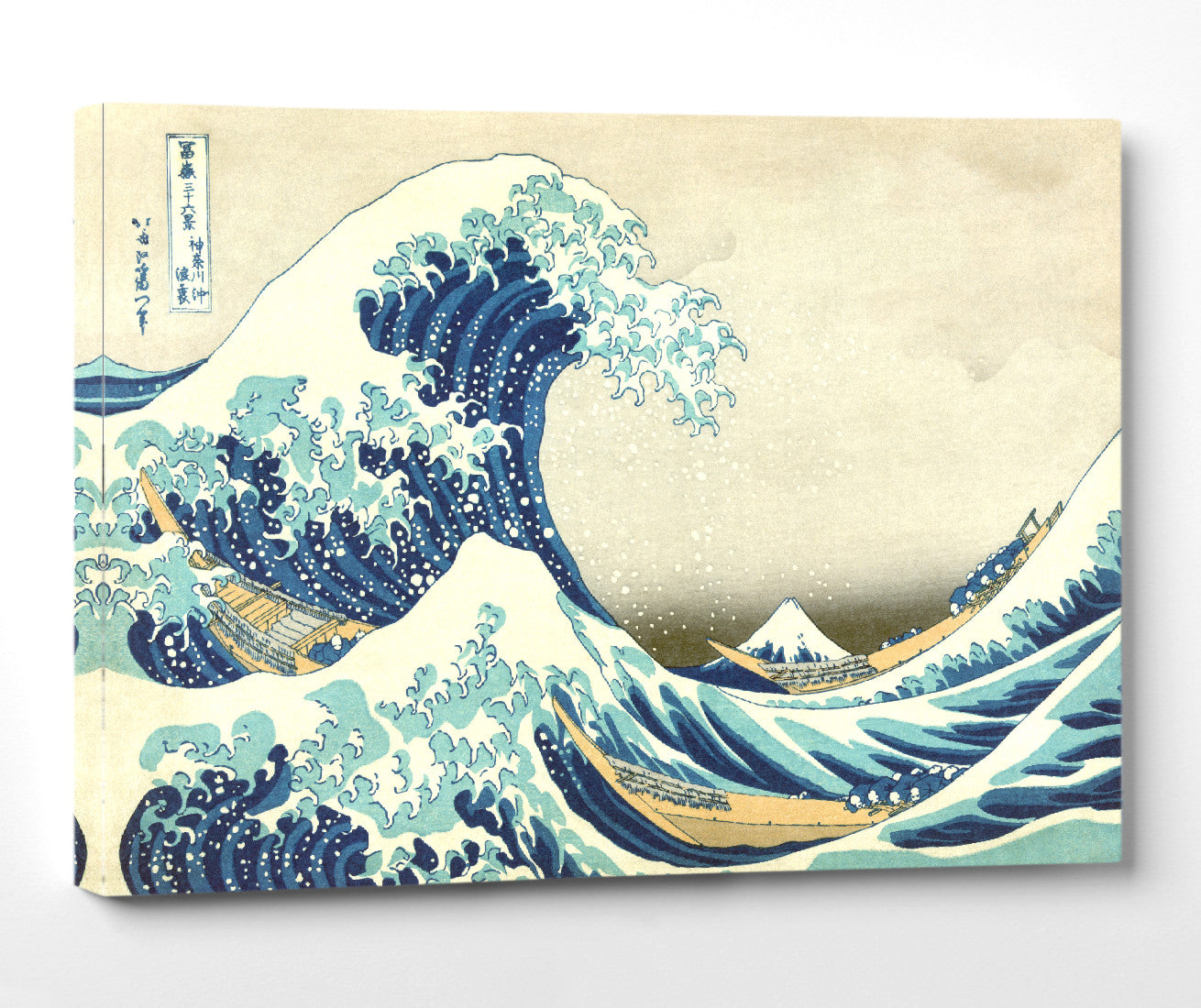

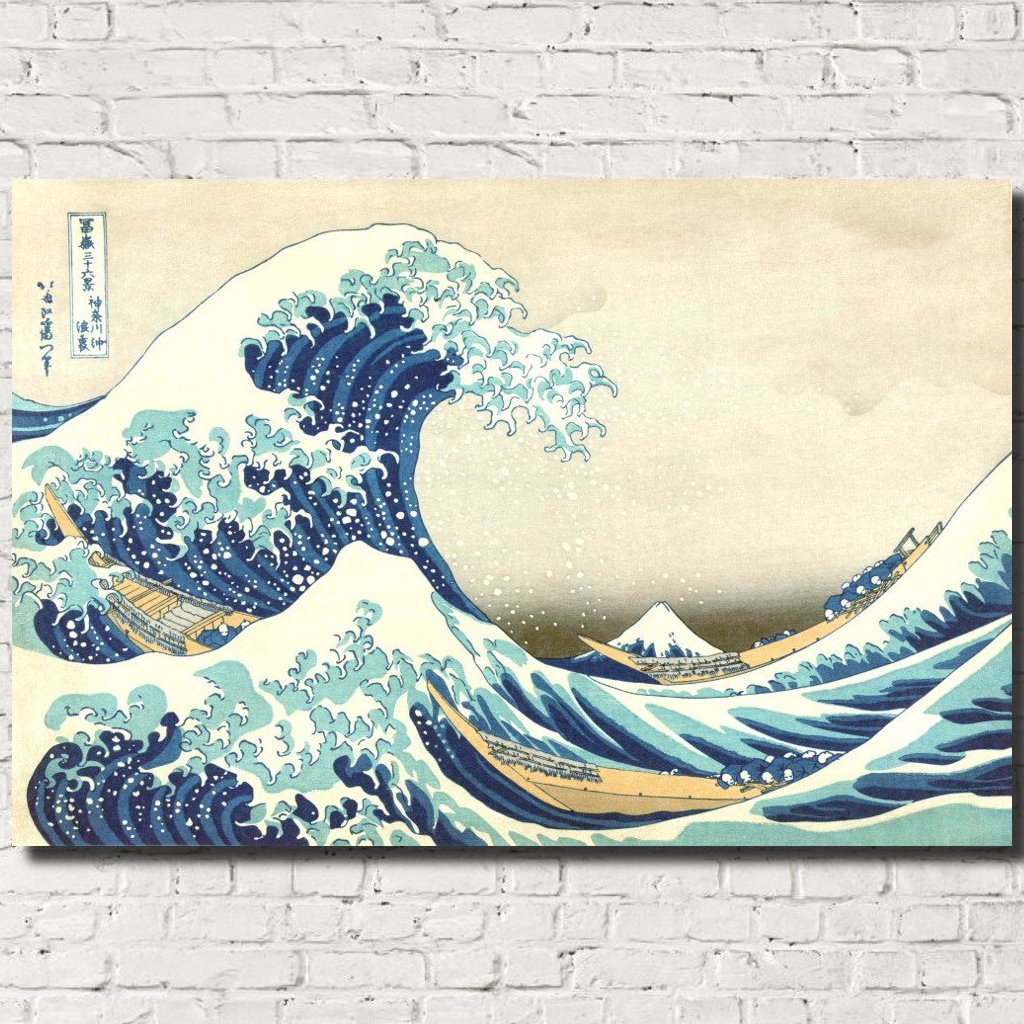

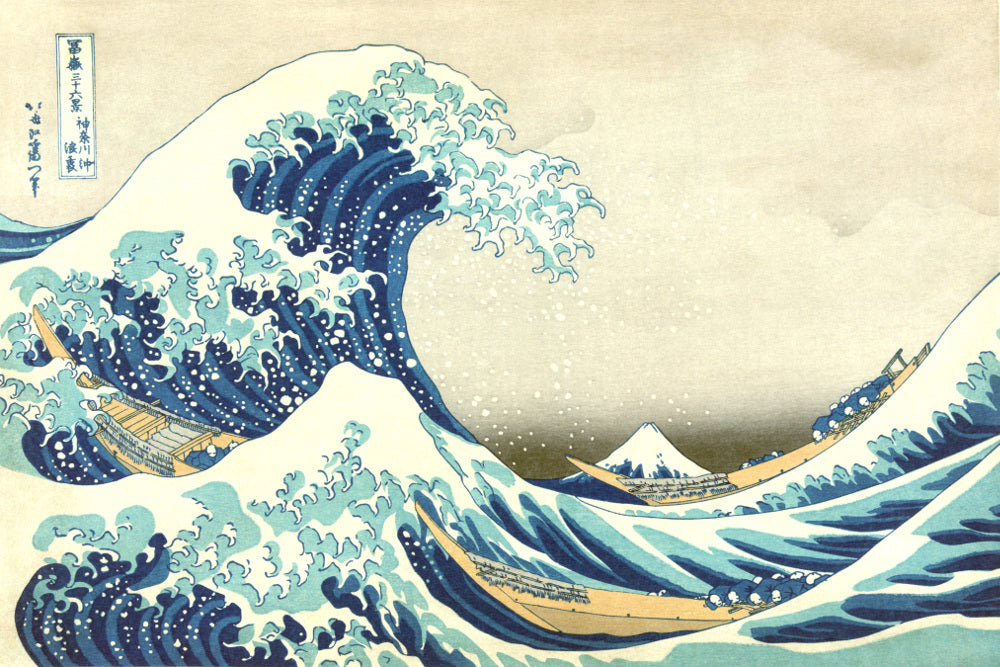

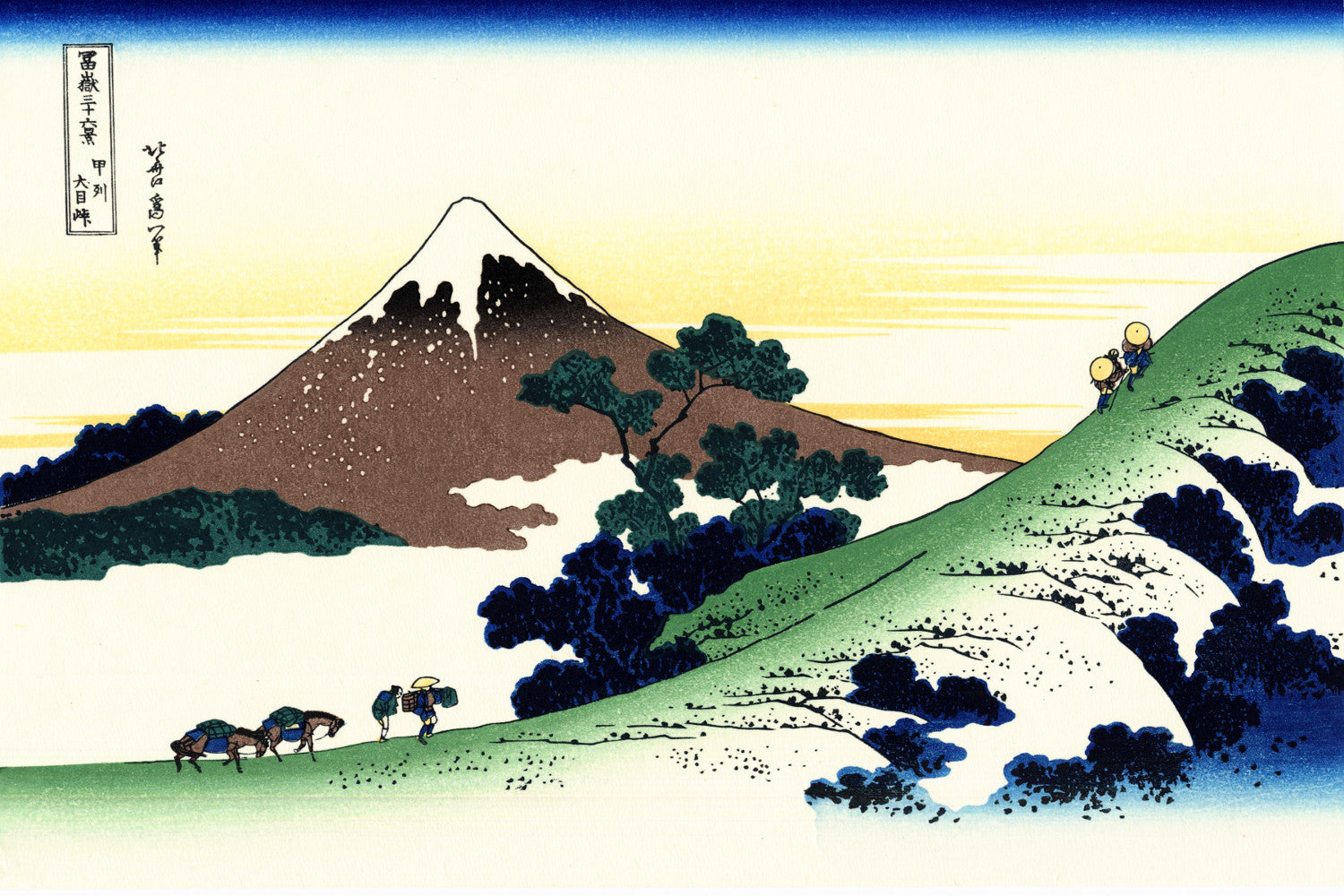

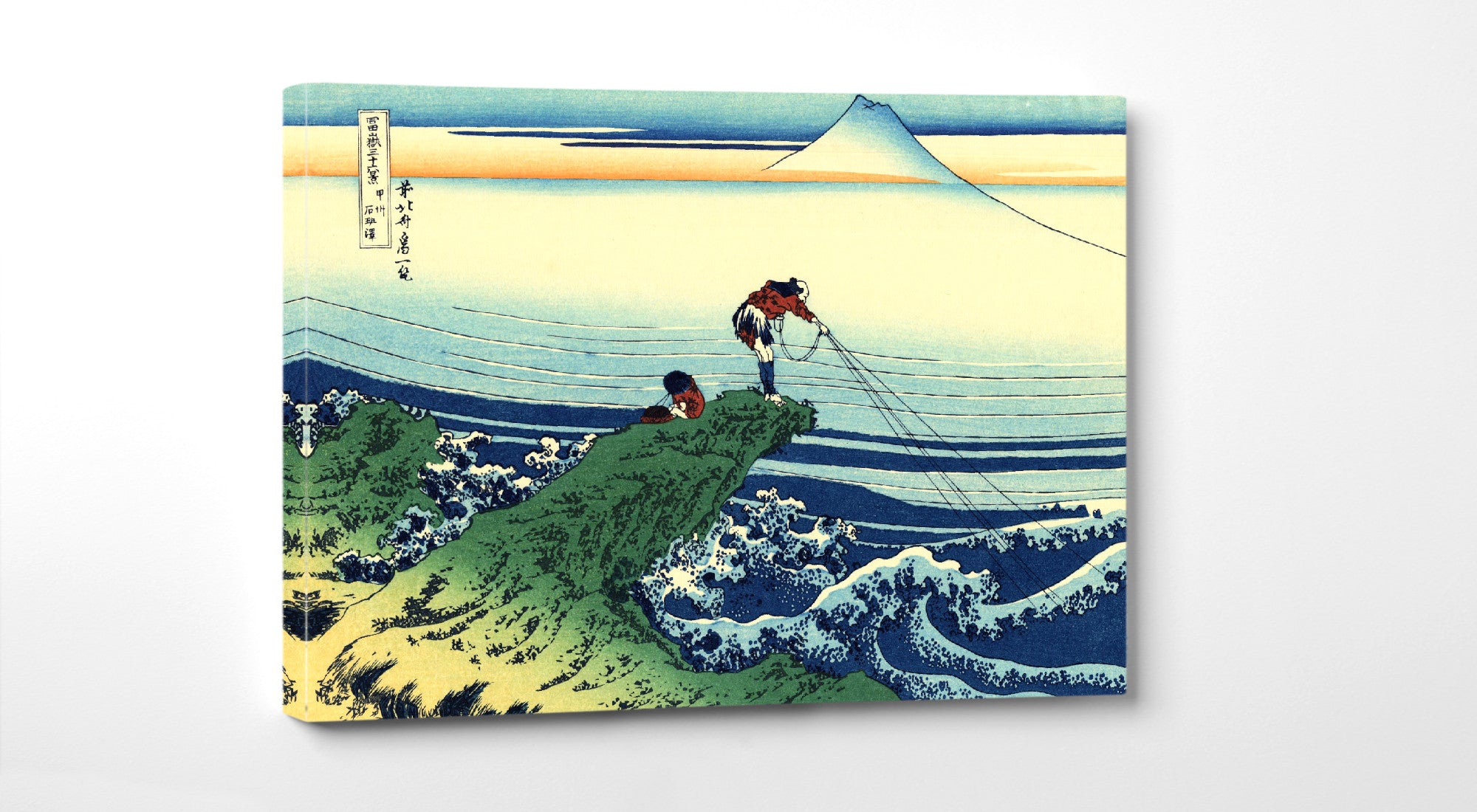

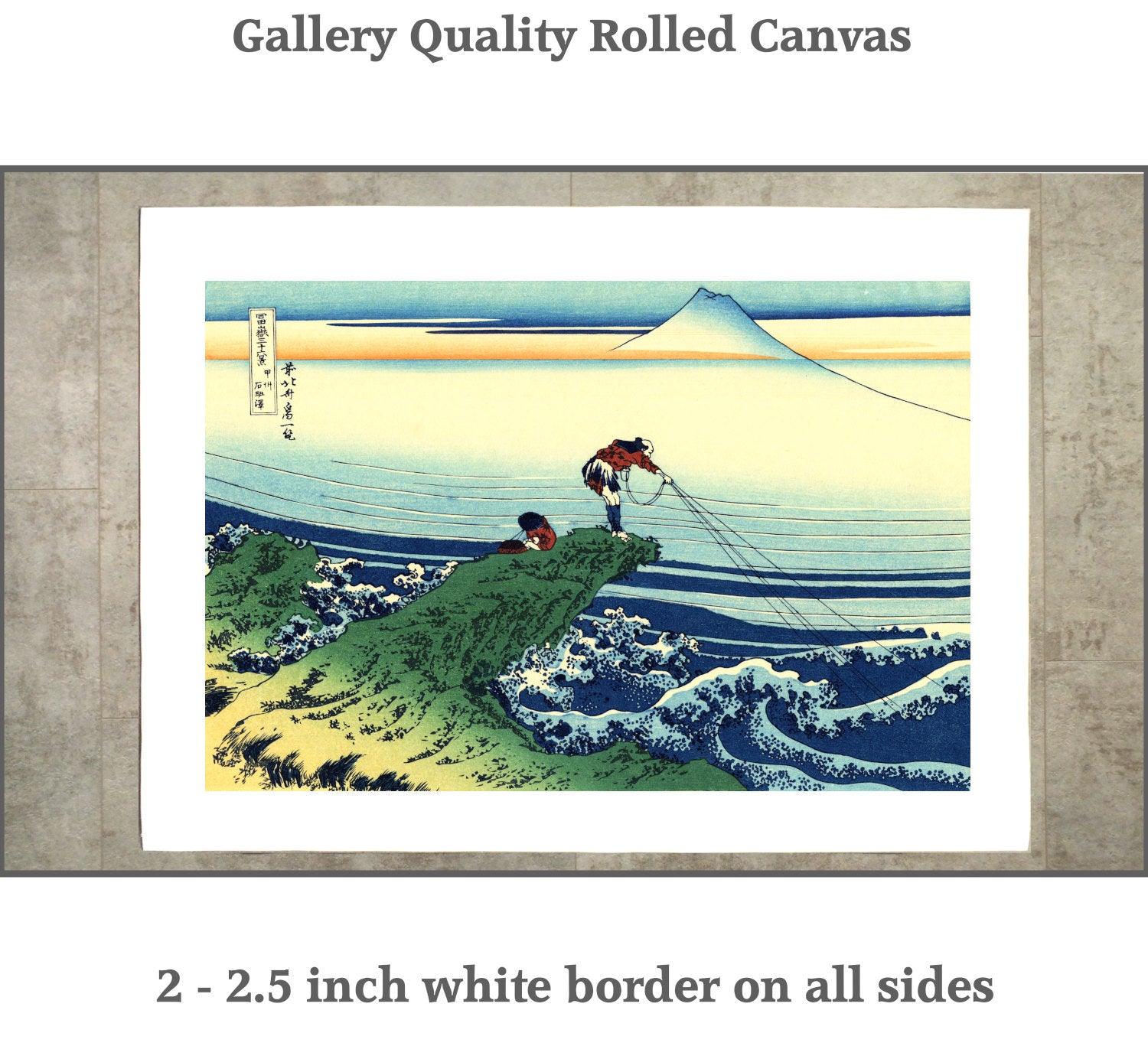

- Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849): Best known for his series "Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji," which includes the iconic "The Great Wave off Kanagawa."

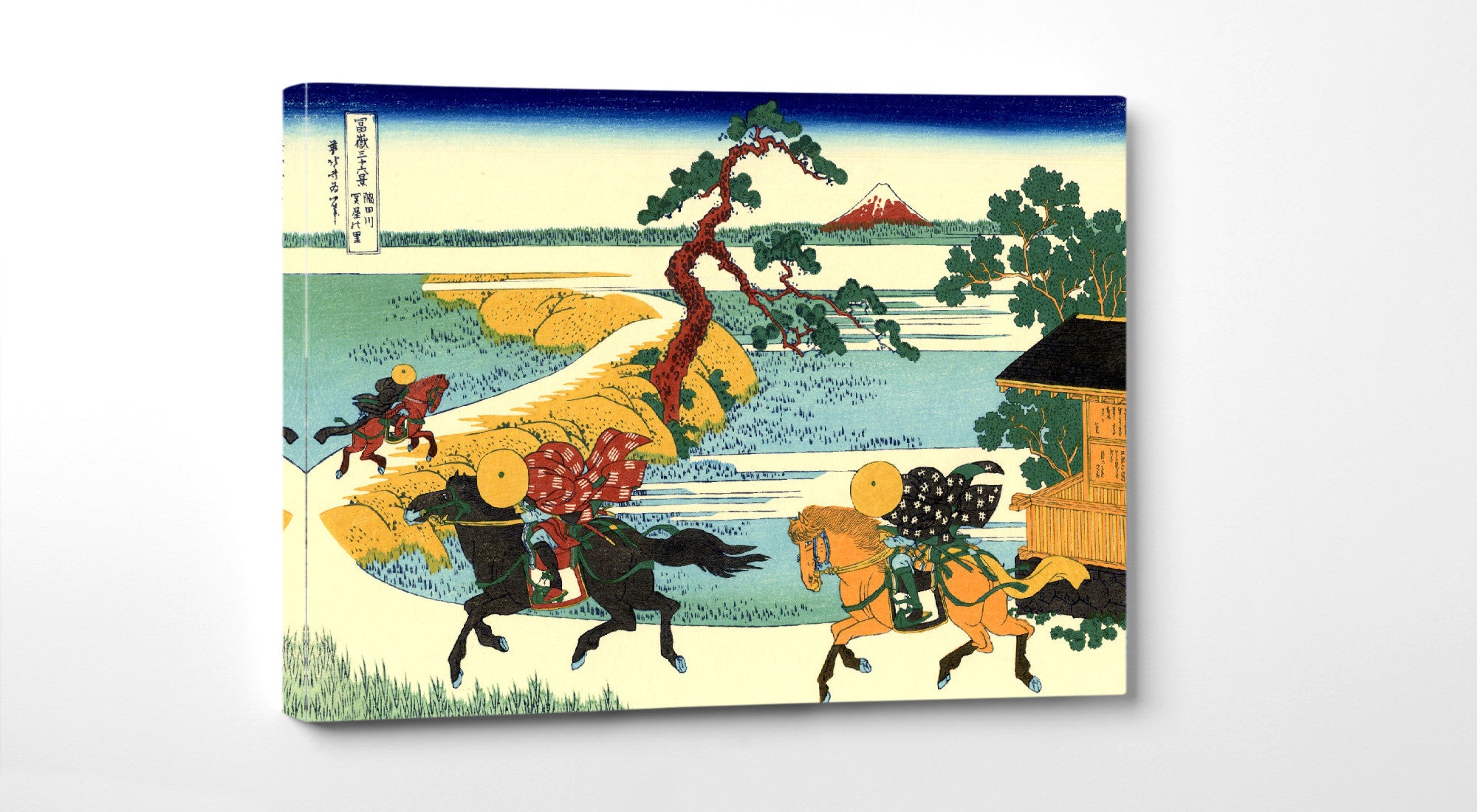

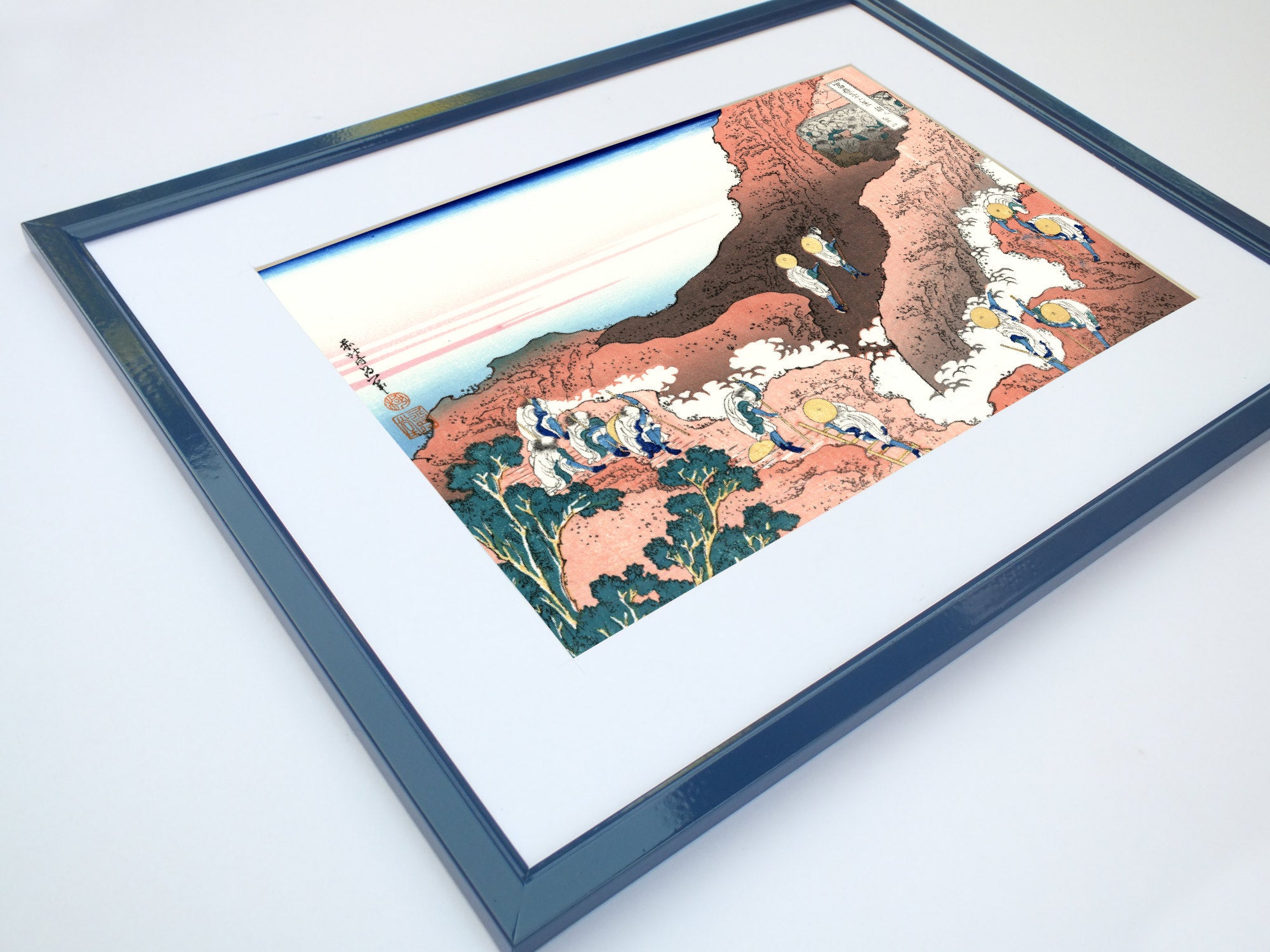

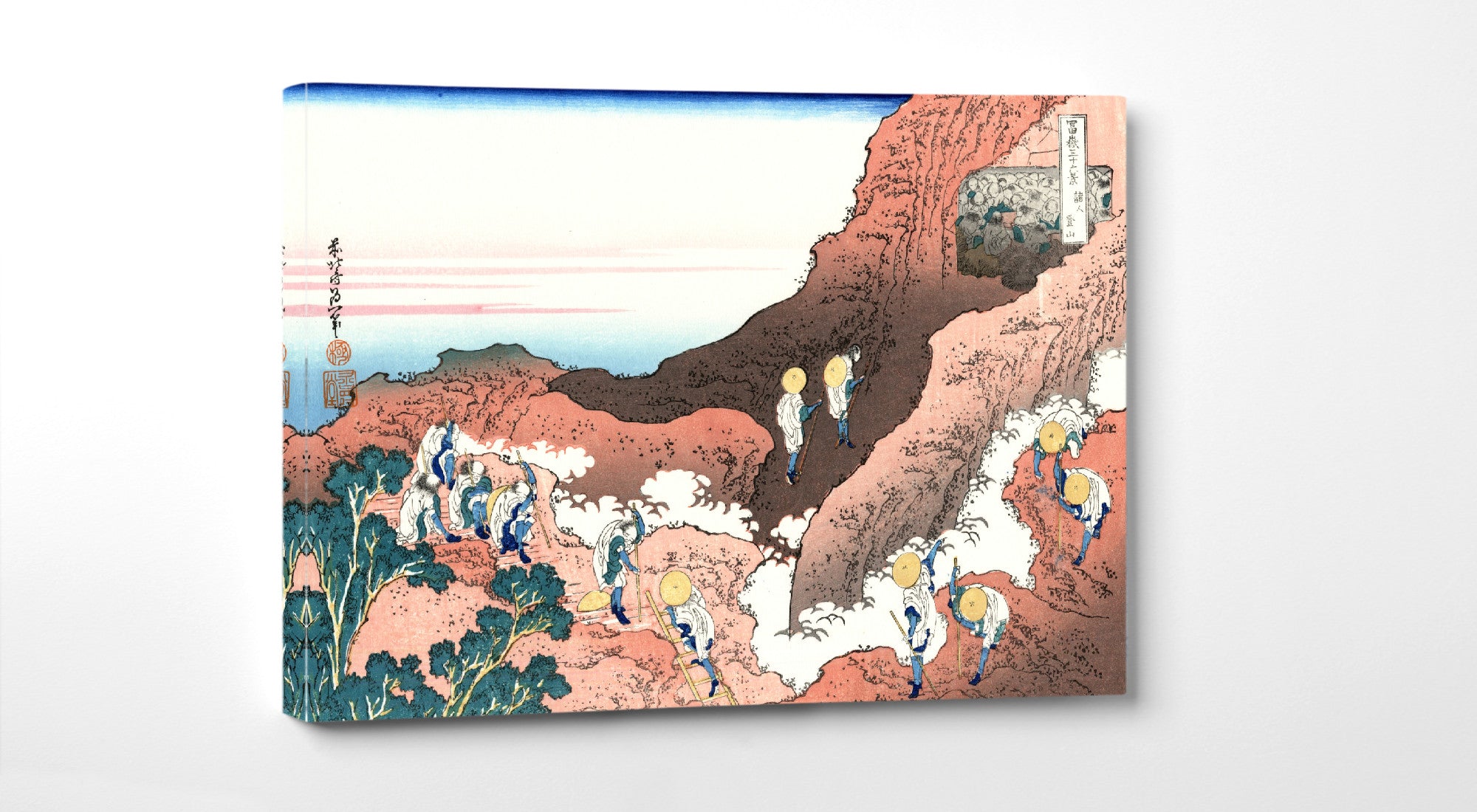

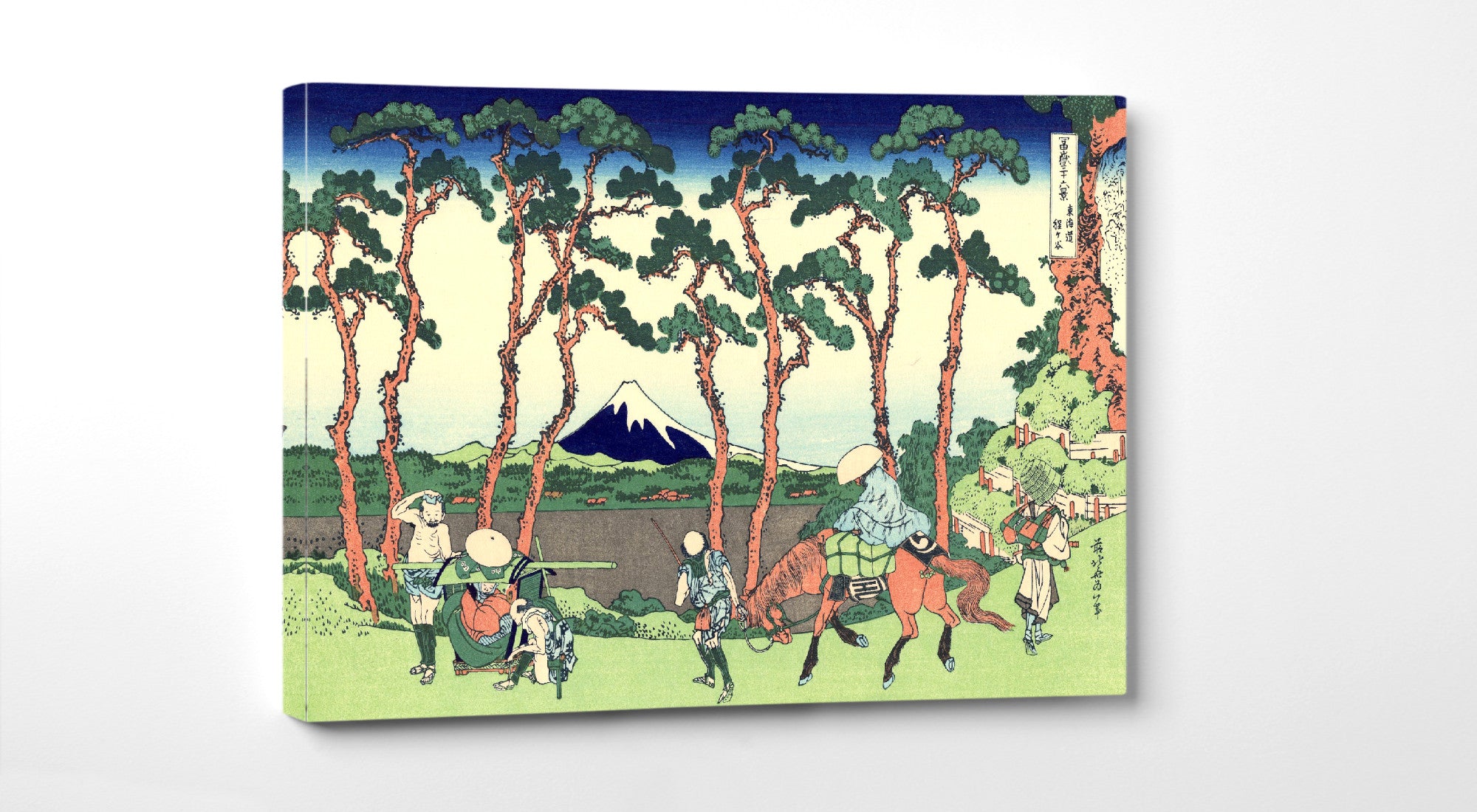

- Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858): Famous for his landscape series, particularly "The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō."

- Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806): Celebrated for his bijin-ga (beautiful women) prints and nature studies.

- Tōshūsai Sharaku (active 1794-1795): Known for his distinctive style of Kabuki actor portraits.

- Suzuki Harunobu (1725-1770): Pioneered the use of full-color nishiki-e printing techniques.

These artists, among others, pushed the boundaries of ukiyo-e, developing new techniques and exploring diverse subjects that captured the imagination of their audience.

Influence on Western Art

The influence of ukiyo-e on Western art, particularly in the late 19th century, cannot be overstated. This phenomenon, known as Japonisme, began when Japanese ports reopened to foreign trade in the 1850s, allowing ukiyo-e prints to reach Europe. Western artists were captivated by the bold compositions, unusual perspectives, and flat areas of color characteristic of ukiyo-e.

Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists such as Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec were particularly inspired by ukiyo-e. They incorporated elements of Japanese aesthetics into their own work, including asymmetrical compositions, unusual viewpoints, and a focus on everyday subjects. Van Gogh, for instance, directly copied several ukiyo-e prints as part of his artistic studies.

Legacy and Modern Interpretations

While the golden age of ukiyo-e ended with the Meiji Restoration in 1868, its influence continued to be felt in Japanese art. The shin-hanga ("new prints") movement of the early 20th century sought to revive traditional ukiyo-e techniques while incorporating Western influences. Contemporary artists continue to draw inspiration from ukiyo-e, reinterpreting its themes and techniques for modern audiences.

Today, ukiyo-e prints are highly valued by collectors and museums around the world. They serve not only as beautiful works of art but also as important historical documents, providing insight into the culture, fashion, and daily life of Edo-period Japan.

The enduring appeal of ukiyo-e lies in its ability to capture the beauty and transience of everyday life. Through their depictions of fleeting moments and ephemeral pleasures, ukiyo-e artists created a visual poetry that continues to resonate with viewers today. As we admire these "pictures of the floating world," we are reminded of the joy and beauty that can be found in the ordinary moments of our own lives.

Related Articles

Ukiyo-e Art: A Journey Through Japanese Woodblock Prints

36 Views of Mount Fuji