The Last Supper, Leonardo Davinci

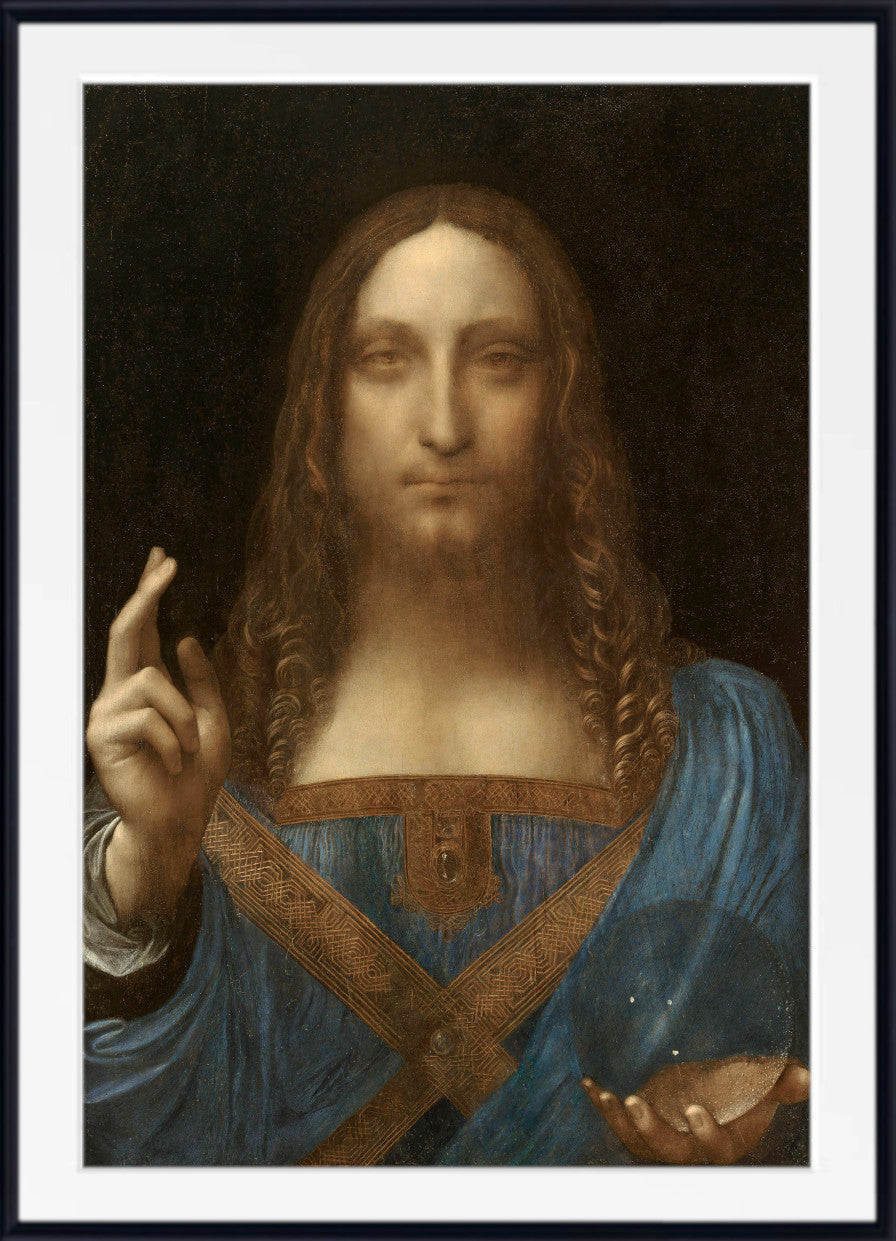

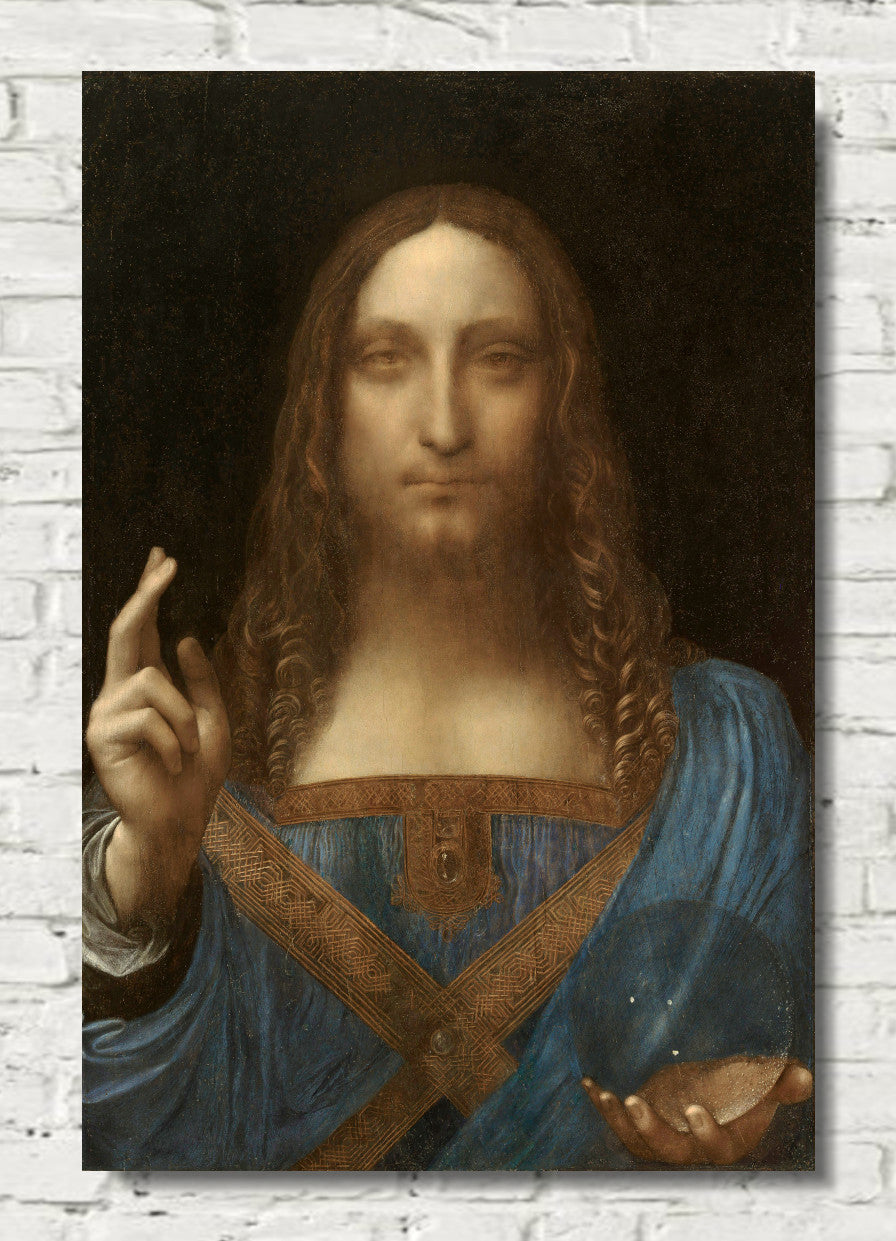

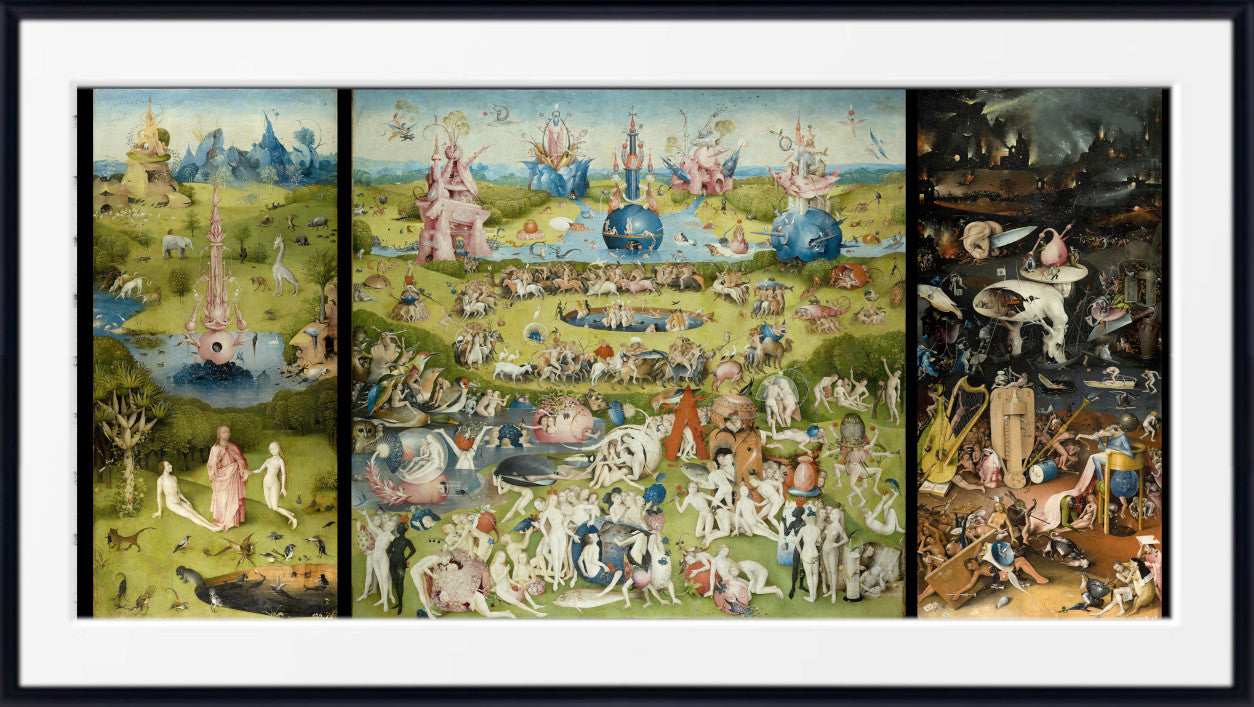

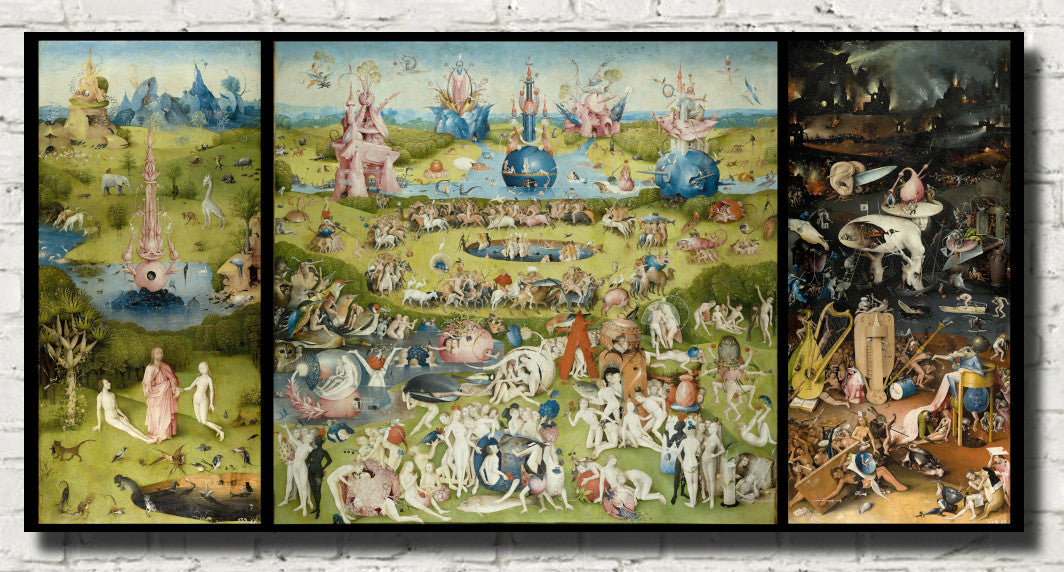

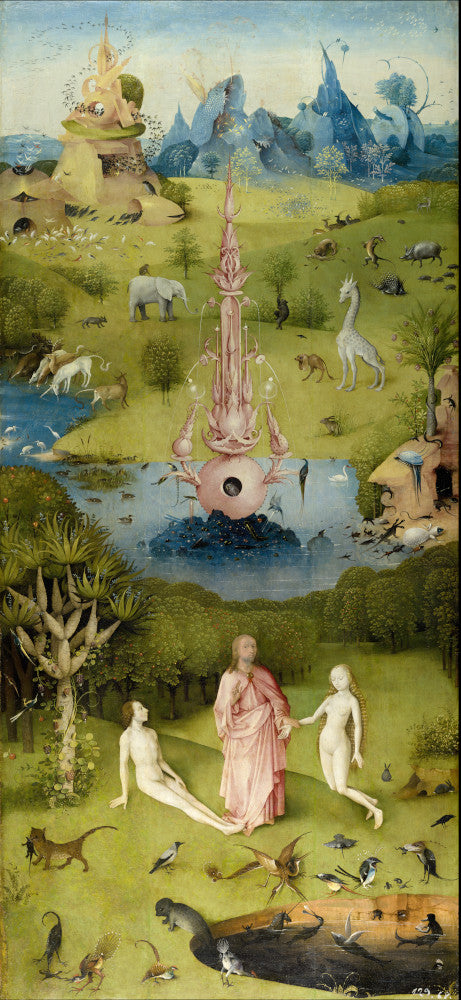

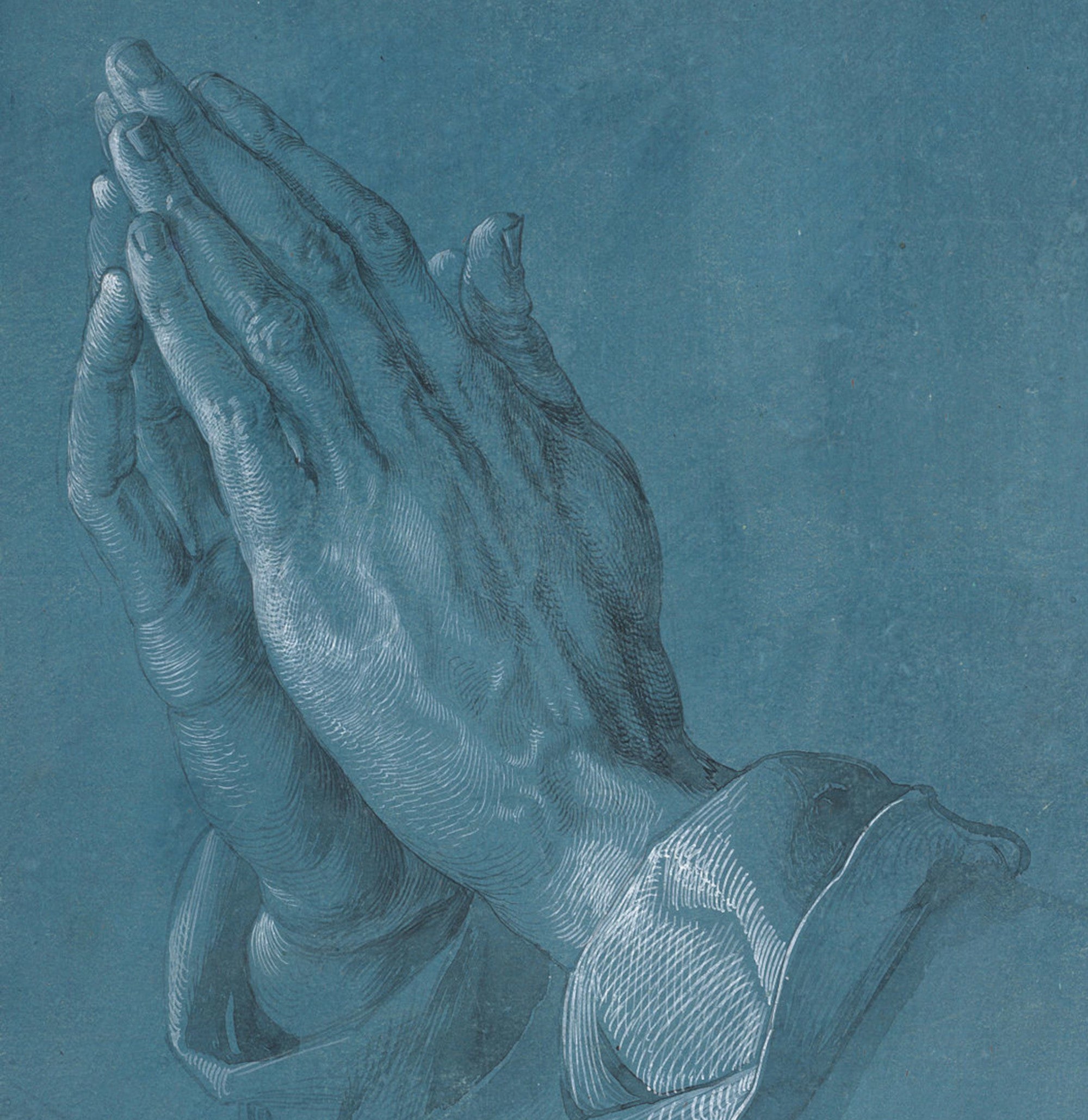

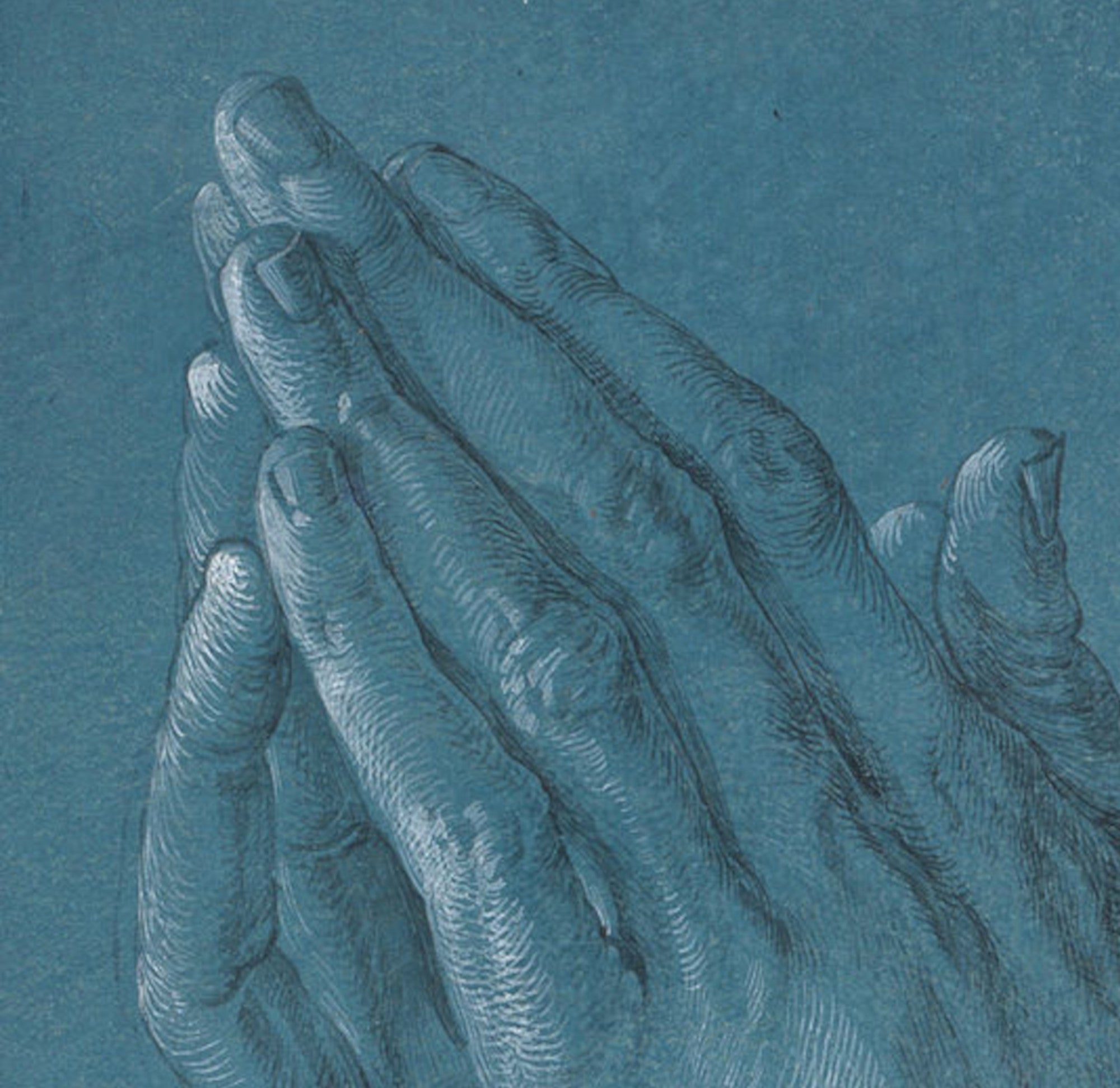

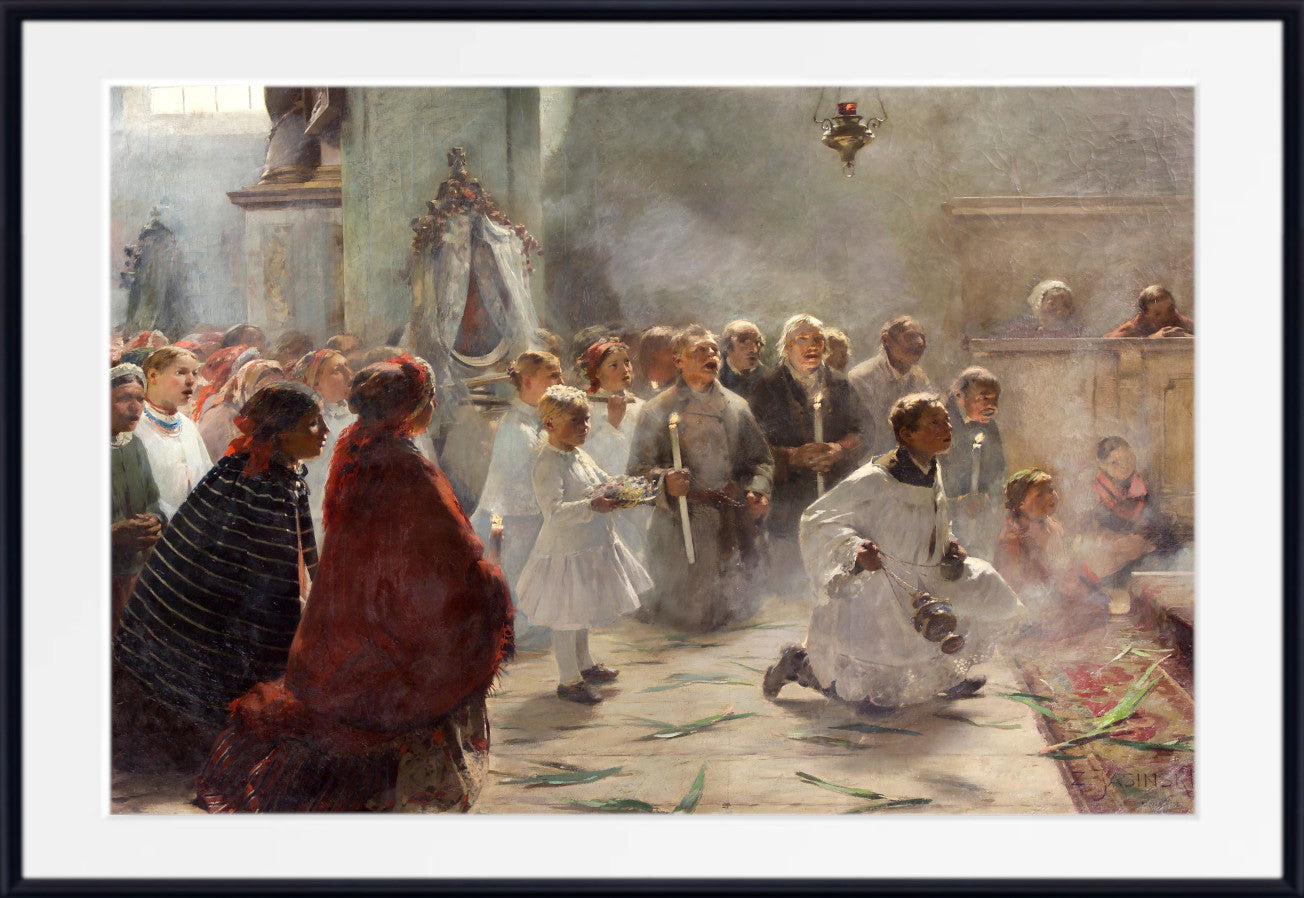

Christian art constitutes an essential element of the religion. Until the 17th century the history of Western art was largely identical with the history of Western ecclesiastical and religious art. During the early history of the Christian church, however, there was very little Christian art, and the church generally resisted it with all its might. From late antiquity to the time of the Counter-Reformation, Western art was essentially the art of the church; both lay and secular patrons commissioned works of art that illustrated important Christian themes and stood as testimony to their own faith. Assuming many forms, Christian art could be found in private homes, churches, and public spaces. Churches, themselves artistic triumphs, were adorned with a broad range of art, including statuary, paintings, and stained glass.

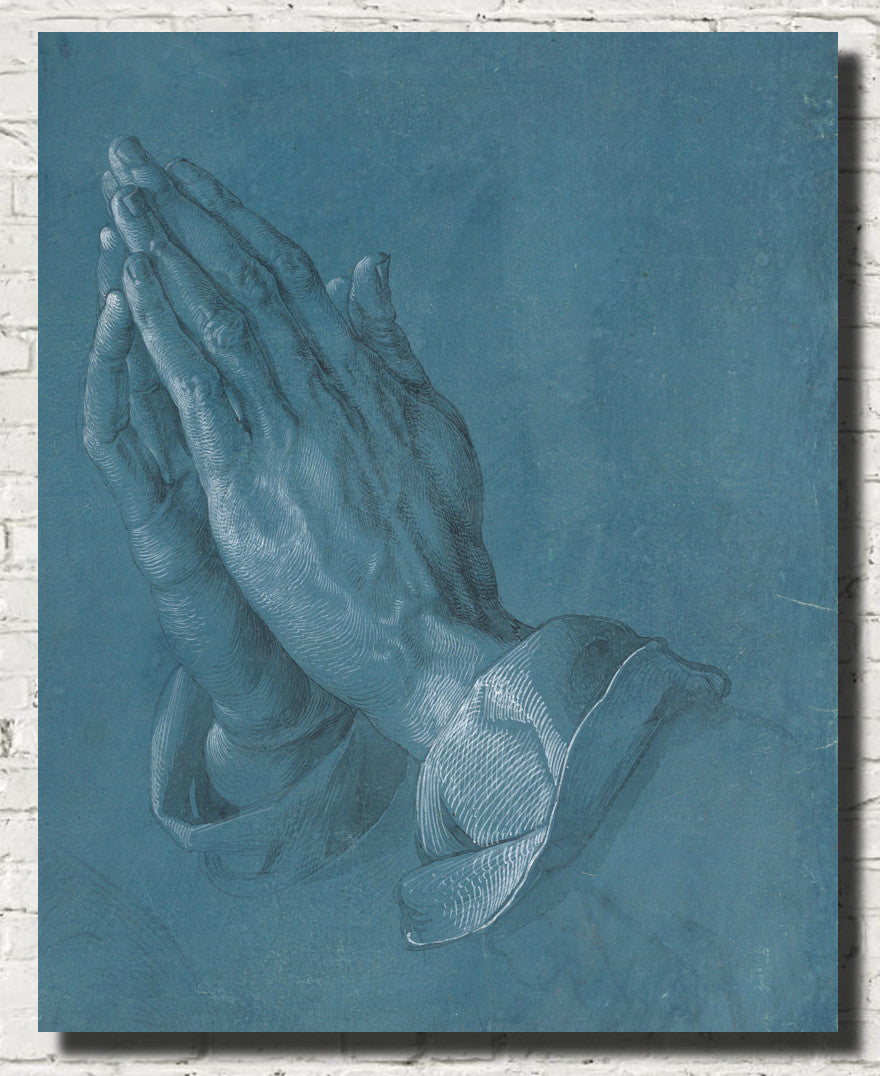

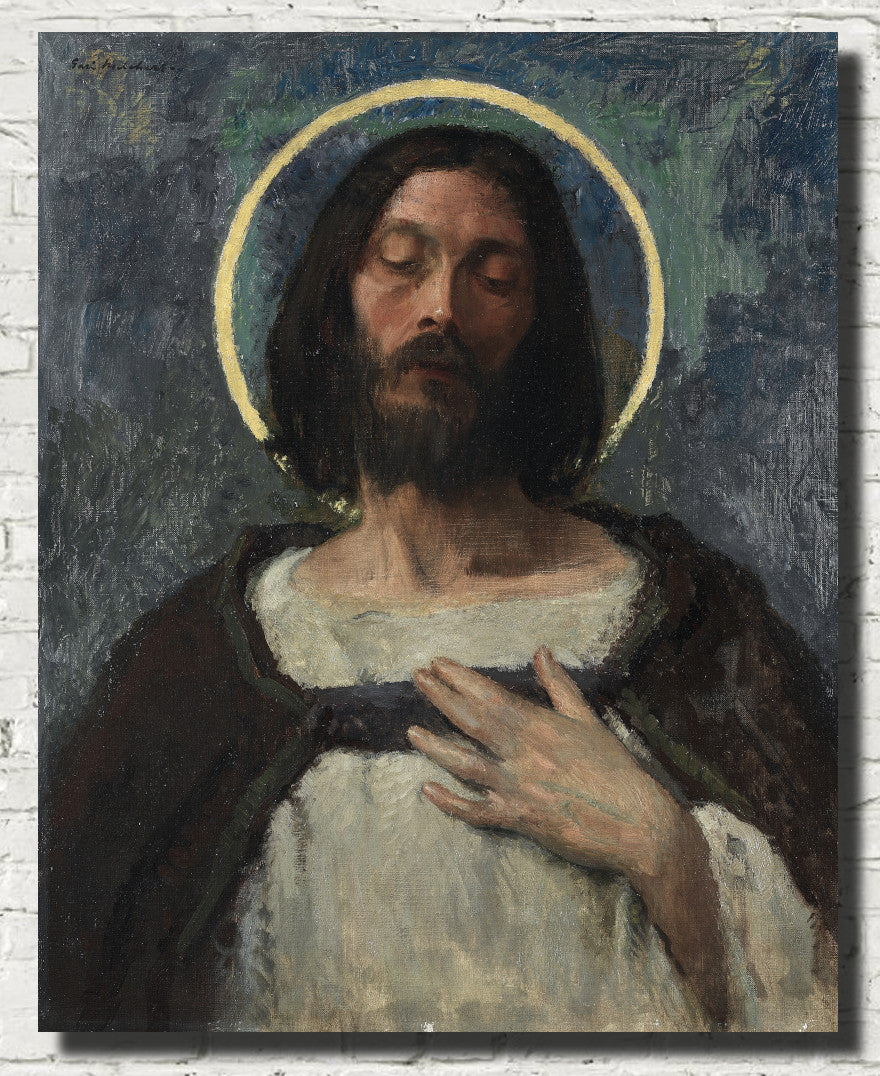

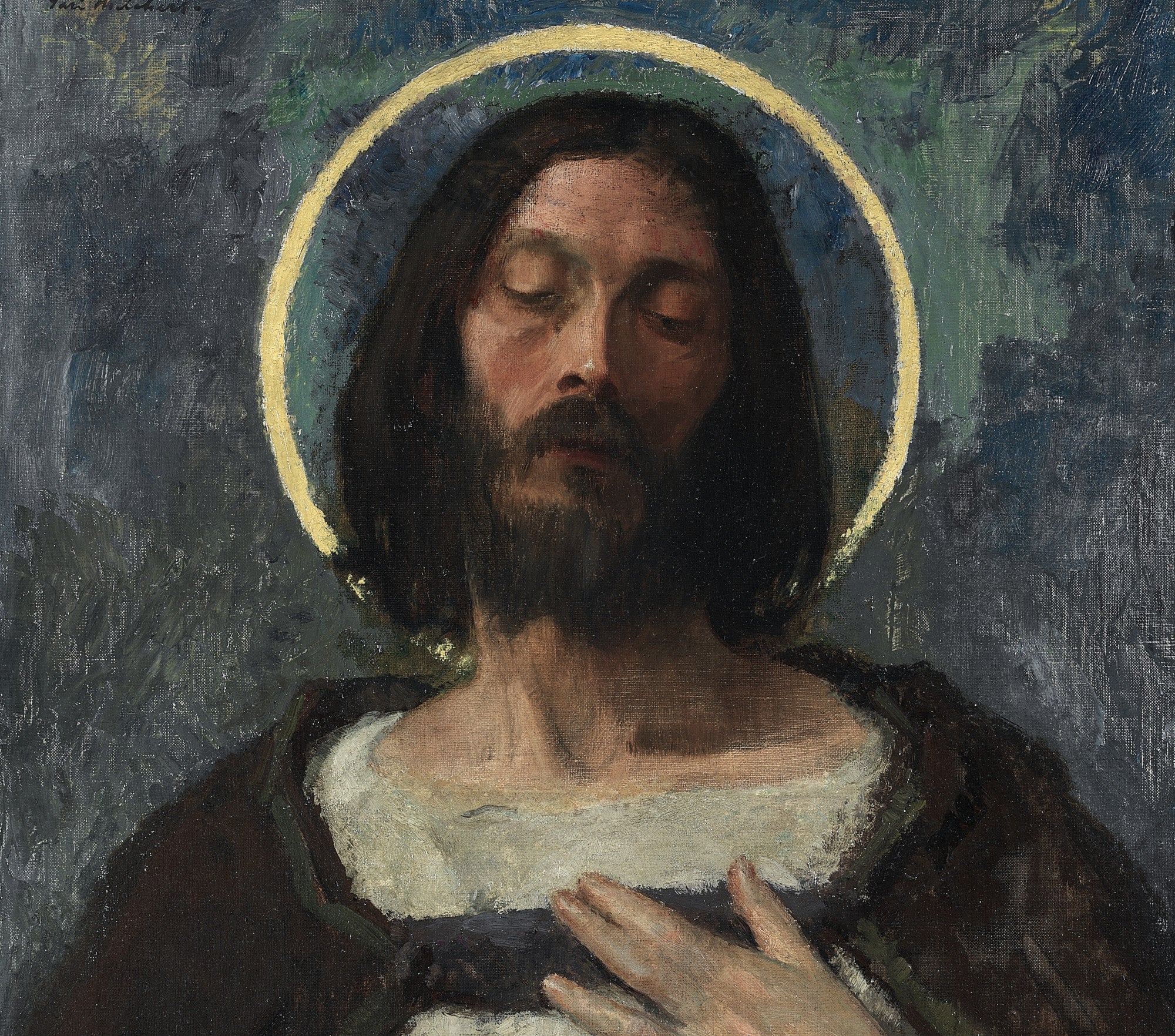

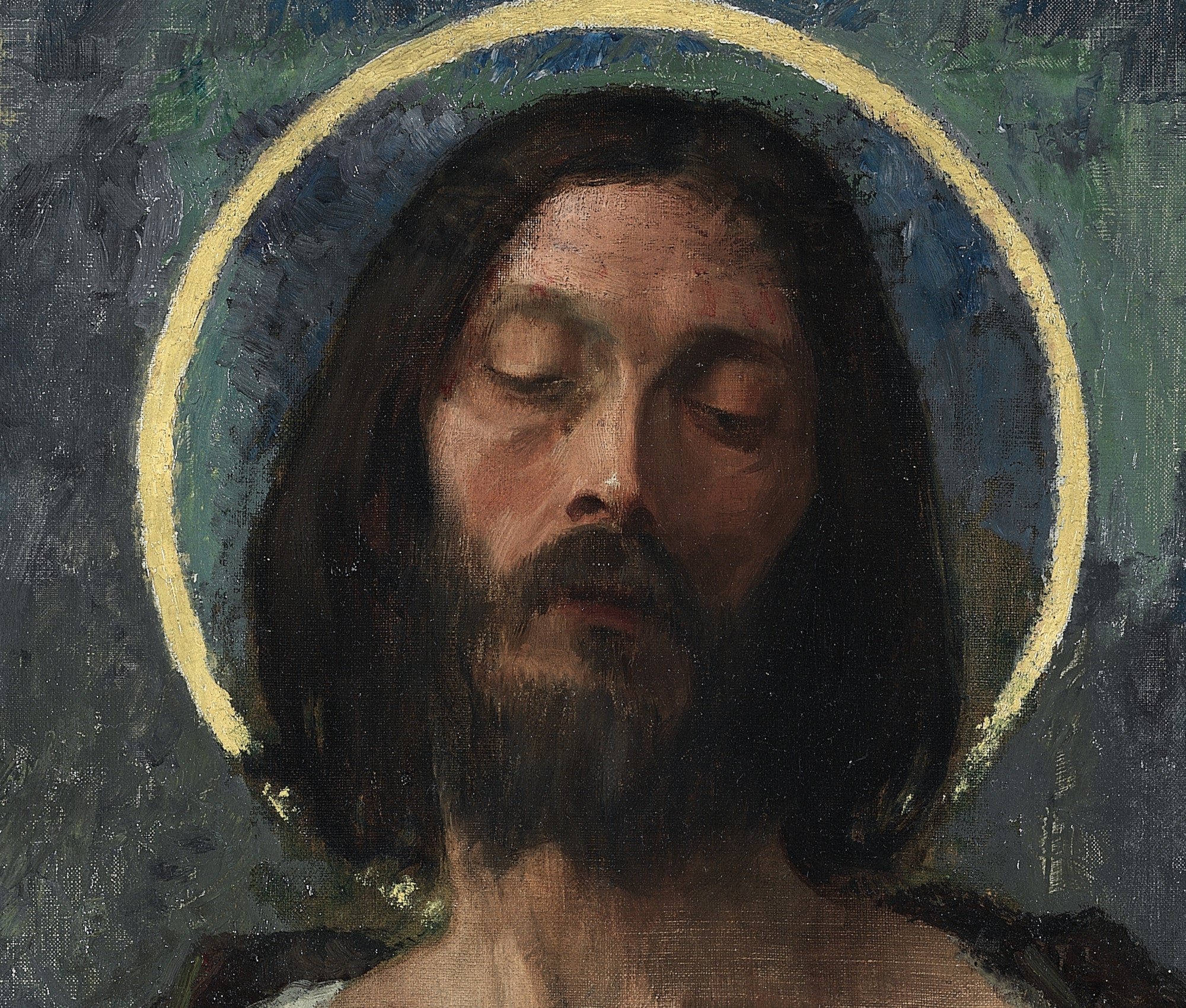

Since the 1800s, devotional art has become very common in Christian homes, both Protestant and Catholic, often including wall crosses, embroidered verses from the Christian Bible, as well as imagery of Jesus. In Western Christianity, it is common for believers to have a home altar, while dwelling places belonging to communicants of the Eastern Christian Churches often have an icon corner.

The Catholic Church has always used sacred images and statues for the practice of worship. Naturally it doesn’t come to mind that the first Christians were forced to hide their faith and to lead their worshipping in secret places, where, at most, they could use secret symbols incomprehensible to their enemies. However they too gathered the remains of the early martyrs, who were to become saints, and respected and venerated them as objects of worship. Many ancient and modern religions are iconoclastic, or condemn the worship of images: thinking of Islam, which forbids the depiction of the image of Muhammad, but also Protestantism, which once condemned and decreed the destruction of many statues and pictures present in Catholic churches. Even the Bible condemns idolatry, and many passages of Sacred Scripture forbid the construction of statues and images, though such condemnation is directed only to the representation of pagan gods. The Bible forbids idolatry, and not the creation of images for the worship and veneration of the one, true God. In fact, in other scriptures, God Himself ordered men to show their devotion by making statues and objects of veneration. The use of sacred images, the worship of statues of the Virgin Mary Jesus or the saints is thus not contrary to the teachings of the Bible. Indeed, it is somehow the heritage of those first signs of devotion, compassion and love brought by early Christians to those remains of martyrs. It was the Council of Nicaea in 787 that formalized and consecrated the use of sacred images. It was given to them the same level of sacredness given to the cross, and therefore the right to be used in churches, during celebrations or as an object of veneration by the faithful, in private homes and public places. As established by the Council, sacred images could be painted, made in the form of mosaics, carved, woven, provided that they: “are images of the Lord God and Savior Jesus Christ, or the Immaculate Our Lady, the Holy Mother of God, the Saint Angels, the saints and the righteous. ” The veneration of sacred images evolved over the centuries in many forms of popular devotion and has certainly contributed significantly to the spread of the Catholic religion in the world.

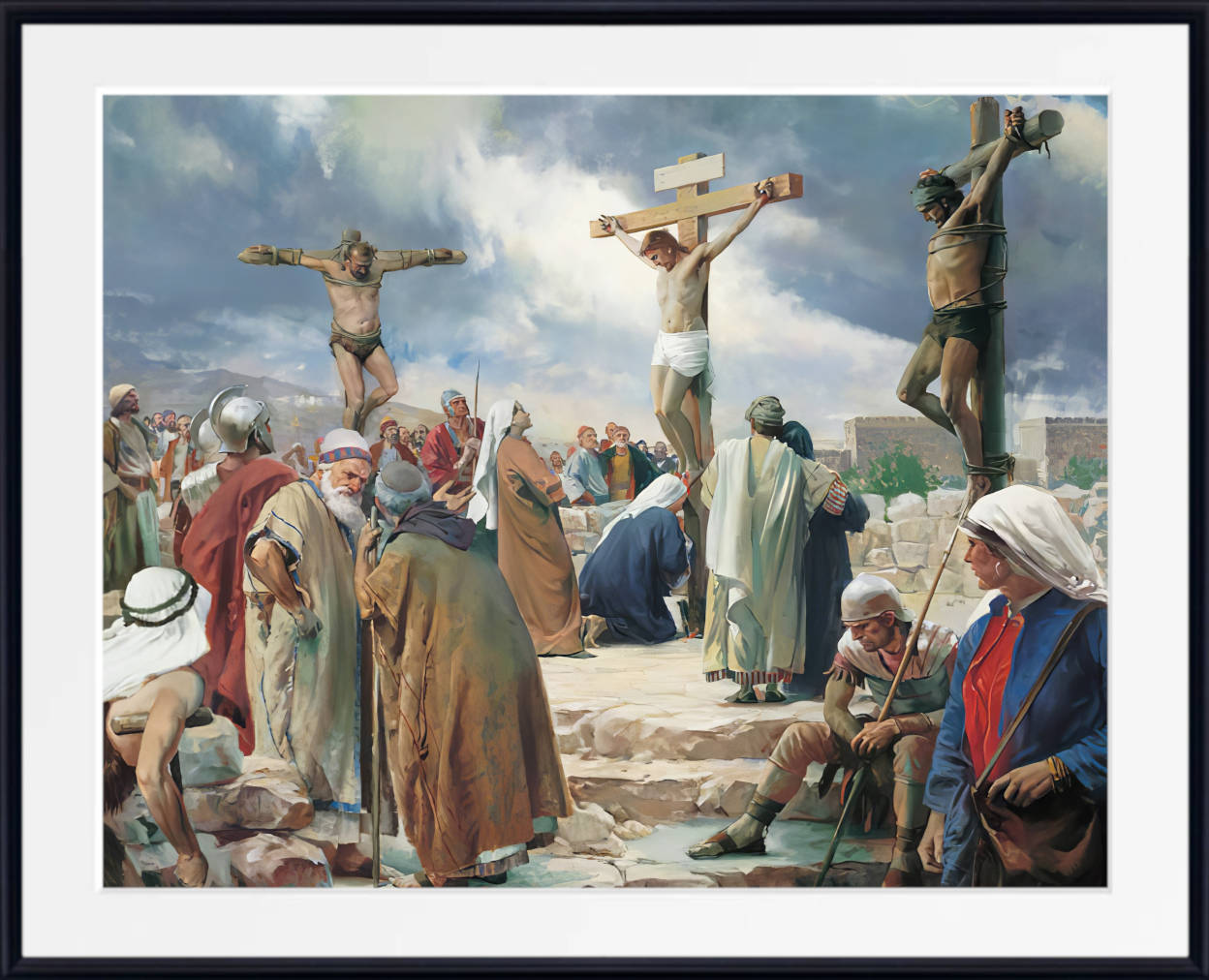

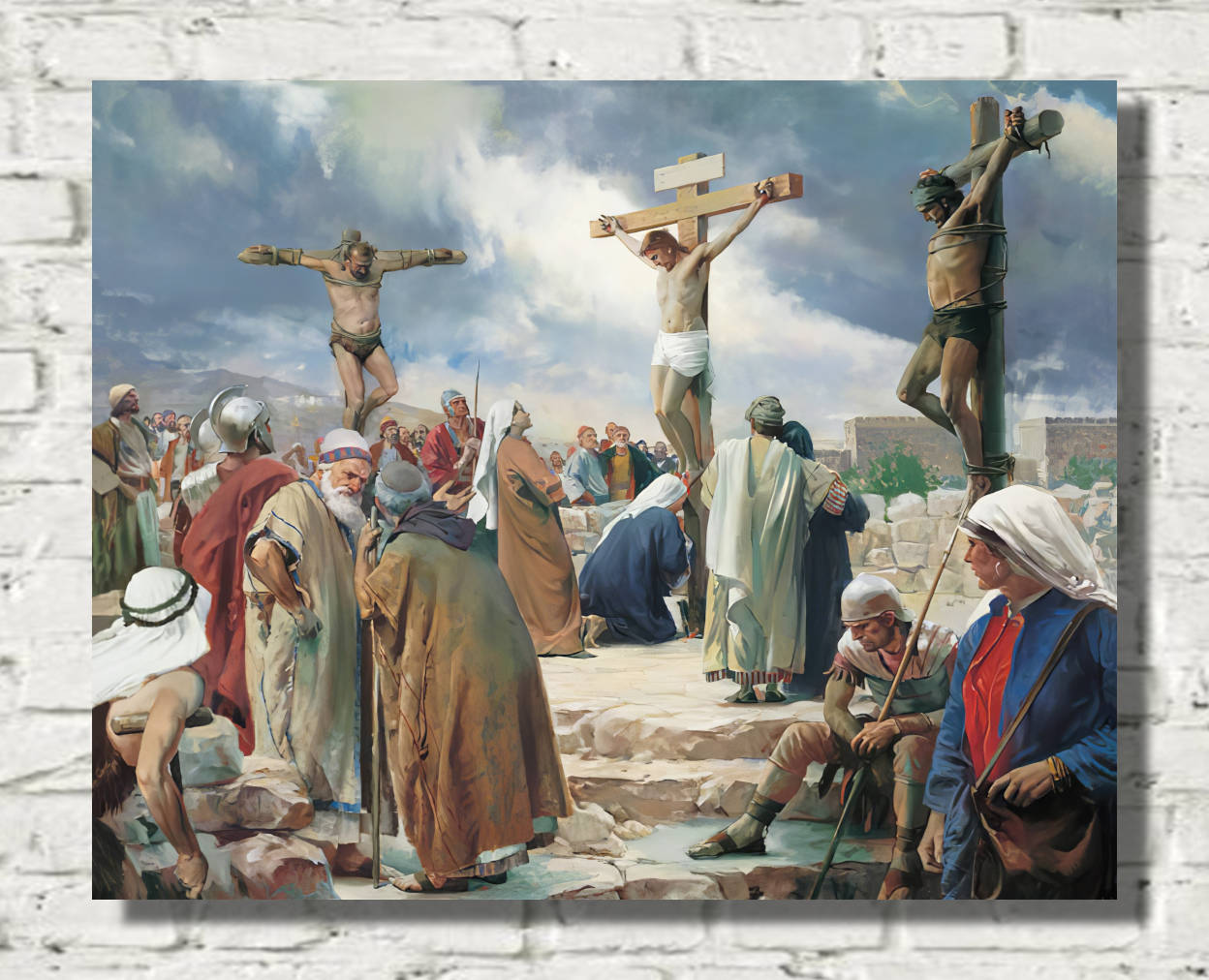

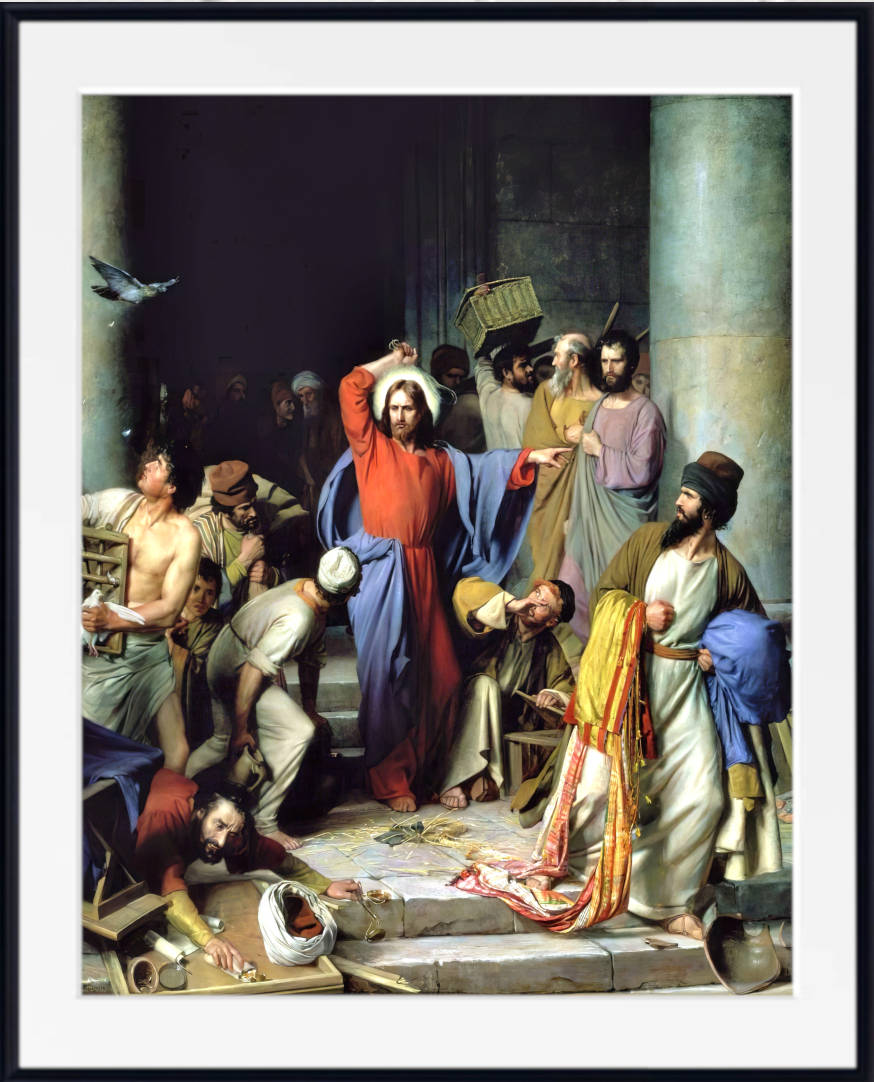

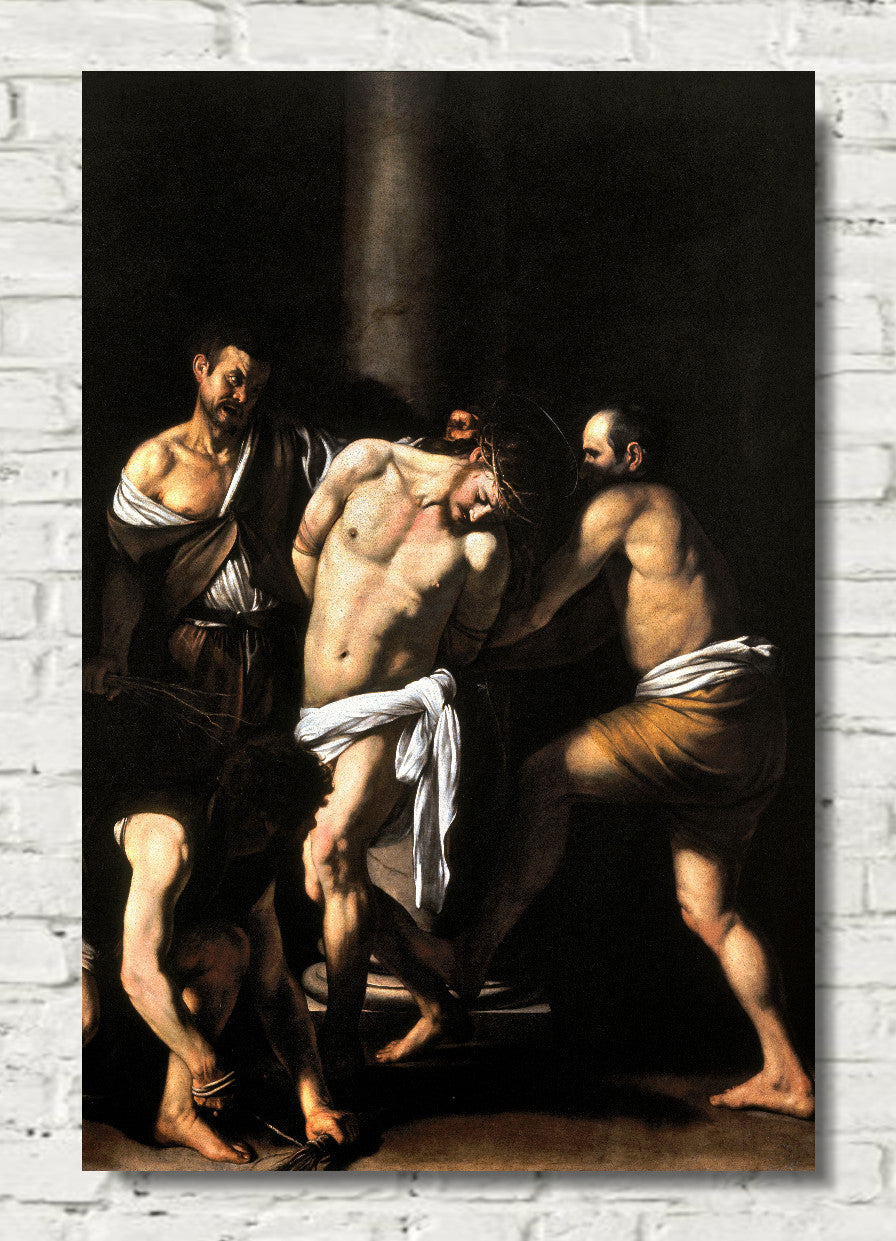

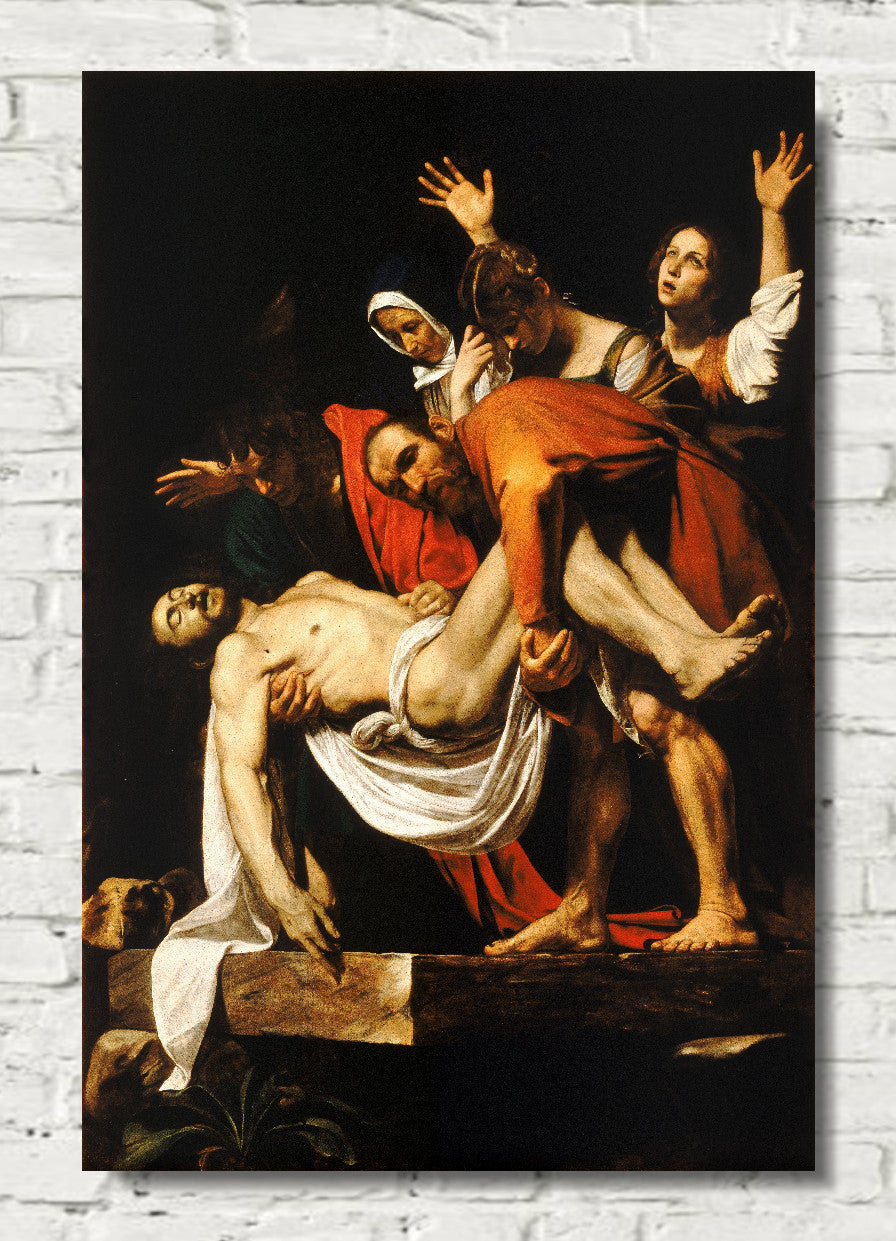

IMAGES OF CRUCIFIXION

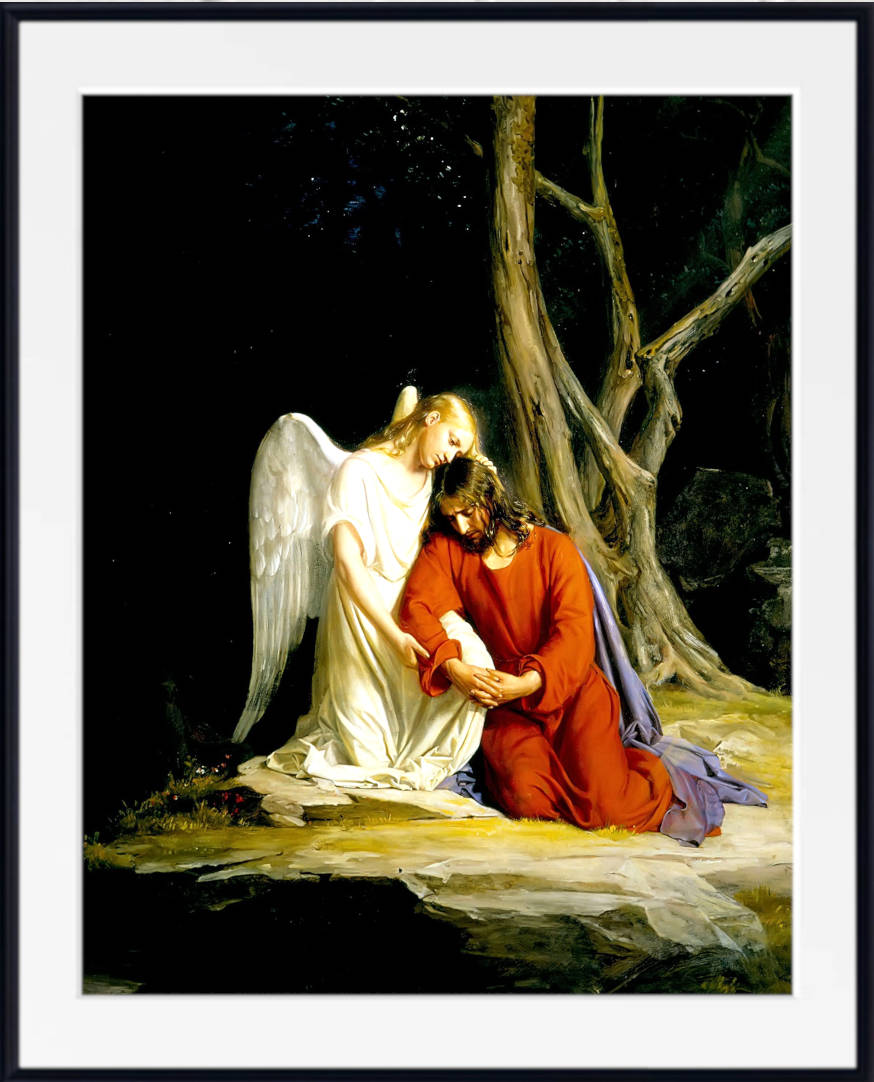

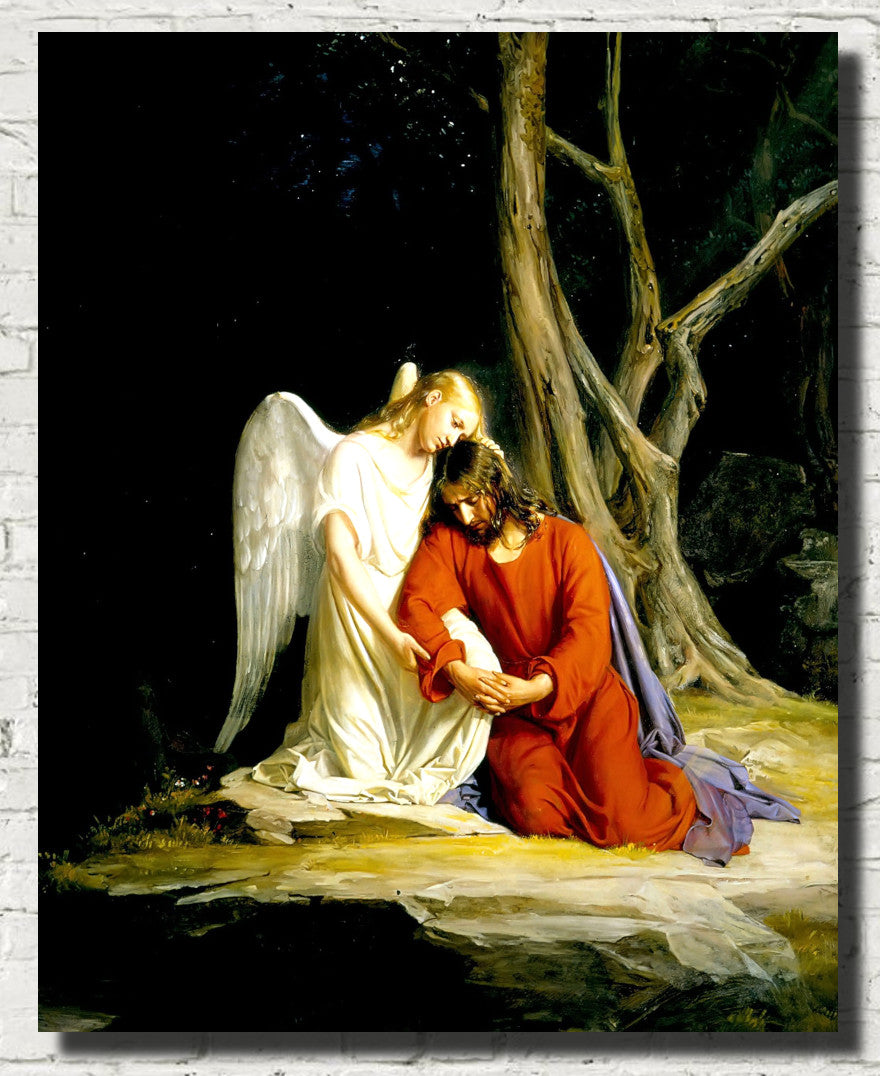

In the Middle Ages crucifixion paintings became widespread. European pilgrims to the Holy Land brought back small metal flasks used for carrying oil, and mass-produced souvenirs decorated with images of the crucifixion. At the same time, ivory reliefs featuring crucifixion scenes were being produced in Italy. Christianity had become the dominant religion in Europe and the cross was becoming a symbol of devotion.

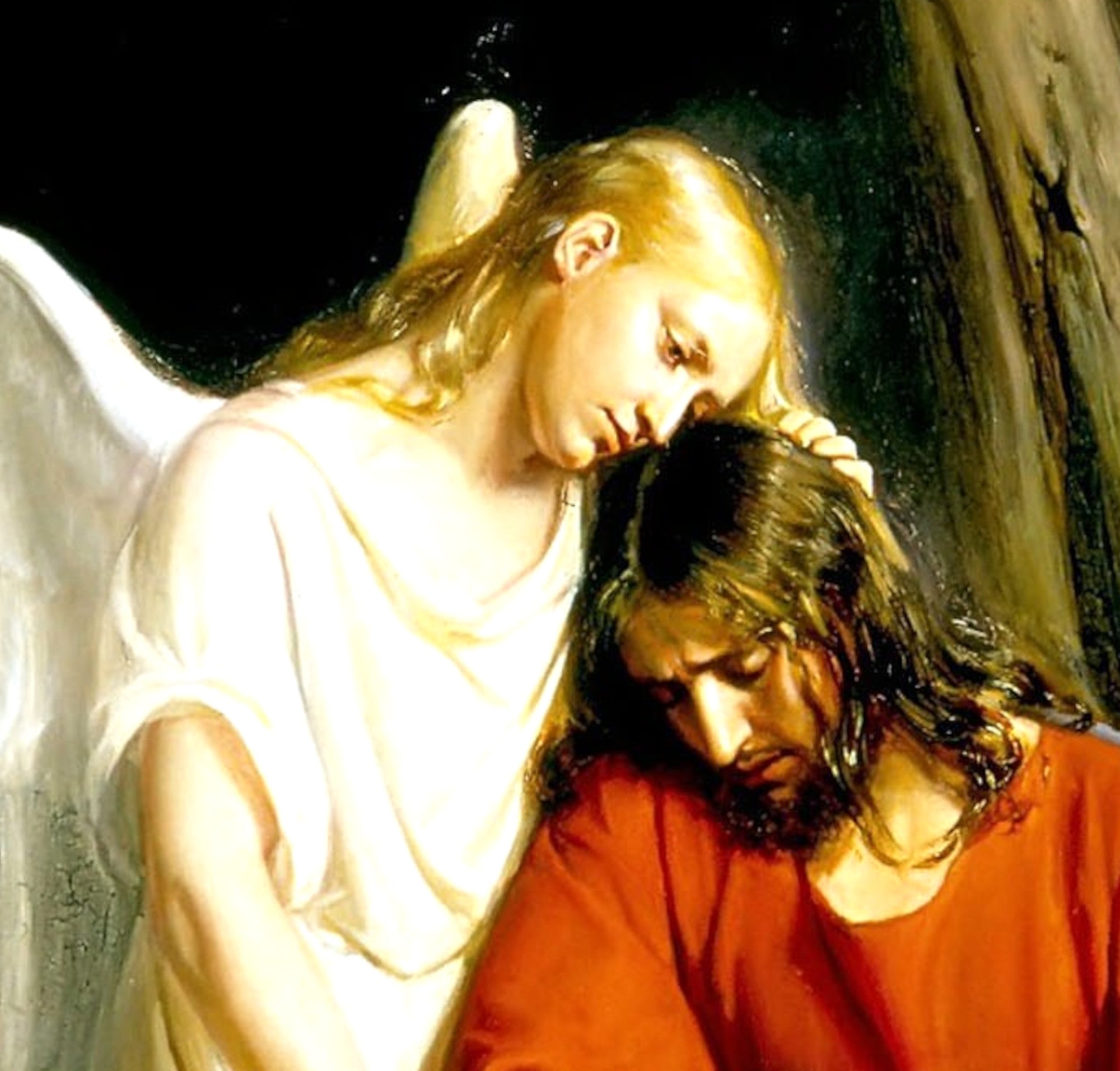

The Passion narrative, which relates the events of Christ’s last week on earth, was a constant focus in Italian painting. Formidable traditions governed the representation of the Crucifixion and other Passion scenes, and yet Italian painters continually renewed them through creative engagement with established conventions. Unlike the stories associated with Christ’s birth, the episodes of the Passion are colored by painful emotions, such as guilt, intense pity, and grief, and artists often worked to make the viewer share these feelings. In this, they supported the work of contemporary theologians, who urged the faithful to identify with Christ in his sufferings that they might also hope to share his exaltation.

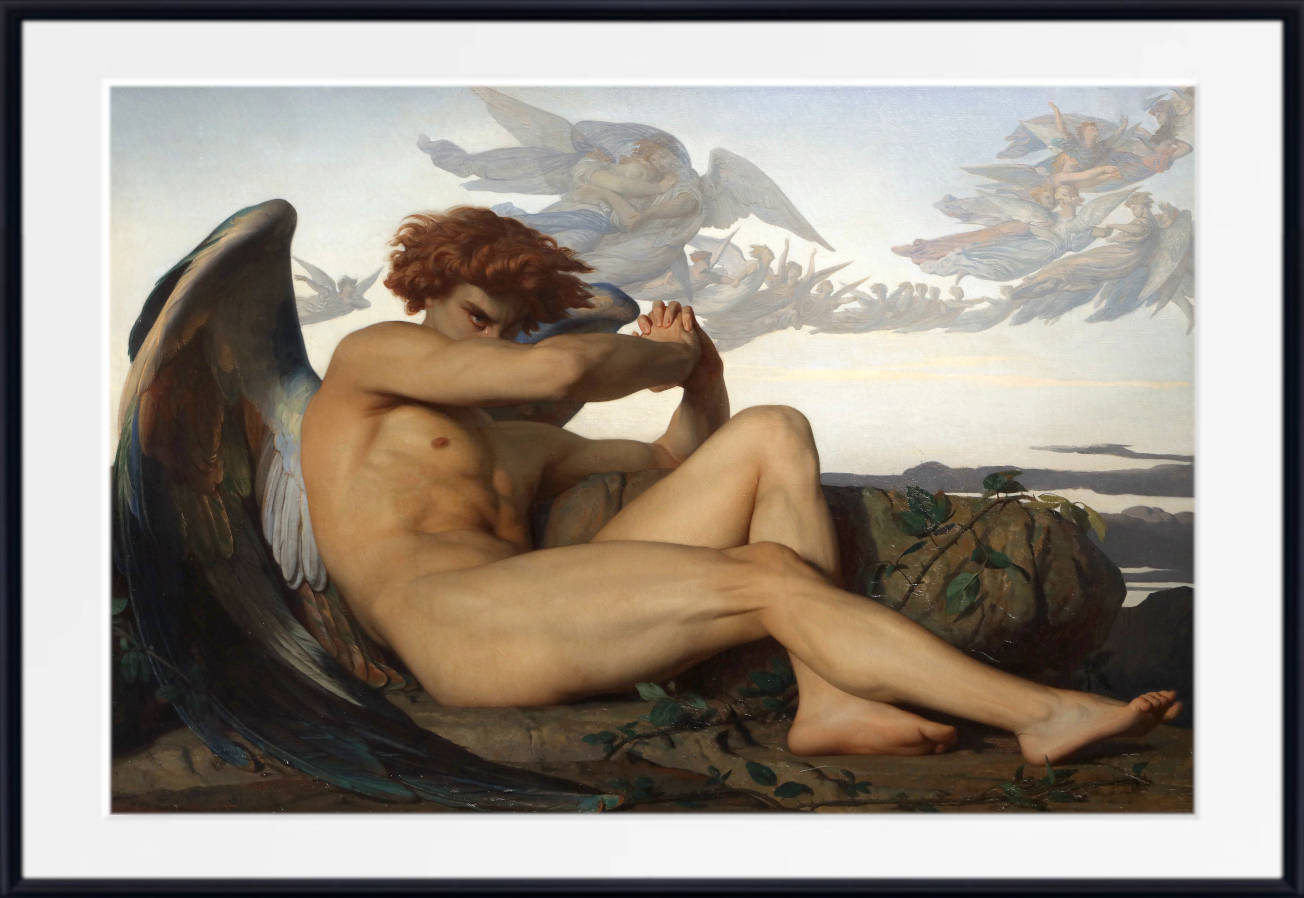

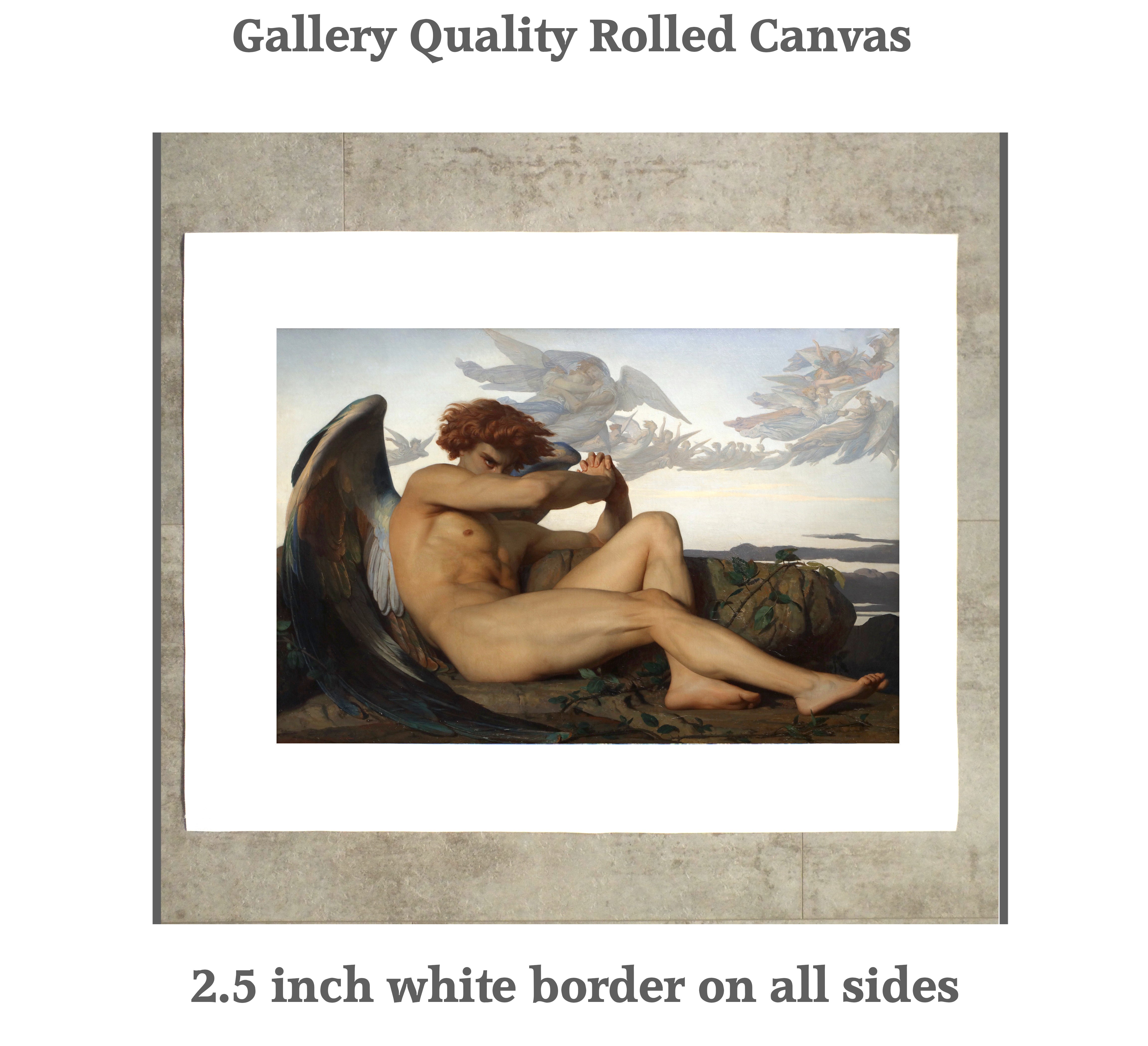

The 1897 crucifixtion painting "Compassion" by William Adolphe Bouguereau may, at first glance, appear to be simply a depiction of Christ on the Cross, with perhaps another saint, or victim. A depiction not too different from thousands of other paintings of the subject; but in fact, the subject of this painting is not simply the event, but the conversion to Christianity through the compassion for the sacrifice Jesus made. The man with his head on Jesus' chest is a representation of every man and mankind as a whole. The man in the painting of the crucifixion shows the same empathy and bearing his own symbolic cross, has found his way to Jesus and his own redemption. In the bible, when Jesus fell on his way to Calvary, a man from the crowd, Simon of Cyrene, went to Jesus and carried the cross for him, which was the inspiration for this widely accepted symbol. The blood of Christ falls onto his hands, reiterating the blood sacrifice that was made for his benefit. On top of the cross a letter is posted which reads "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews" in three languages, Greek, Latin, and Aramaic. Although in many depictions, Christ is crucified at the top of a mountain, Bouguereau in his painting of Jesus on the Cross chooses to depict the savior on a barren wasteland, symbolic of the man"s spiritual life before finding his way to Christ. Bouguereau chose to keep this painting, which shows the importance his religion played in his own life, and it remained in his studio until its recent donation to the Musèe D'Orsay, Paris, France.

The image of Christ on the Cross has been painted by many artists each with their own nuance - Leon Bonnat was commissioned in 1873 to paint Christ on the Cross for the courtroom of the Cour d'Assises of the Palais de Justice in Paris in order to incarnate divine justice in the eyes of the accused and remind them of the sufferings of Christ to save the fishermen. Presented at the 1874 Salon, Bonnat's painting radically renews the traditional representation of Christ on the cross. The crucified and represented in an extremely realistic way, emphasizing the suffering due to the torture. Bonnat would have modeled on a corpse nailed to planks. Image and historical text by Petit Palais, Museum of Fine Arts of the City of Paris where the painting can be seen on display.

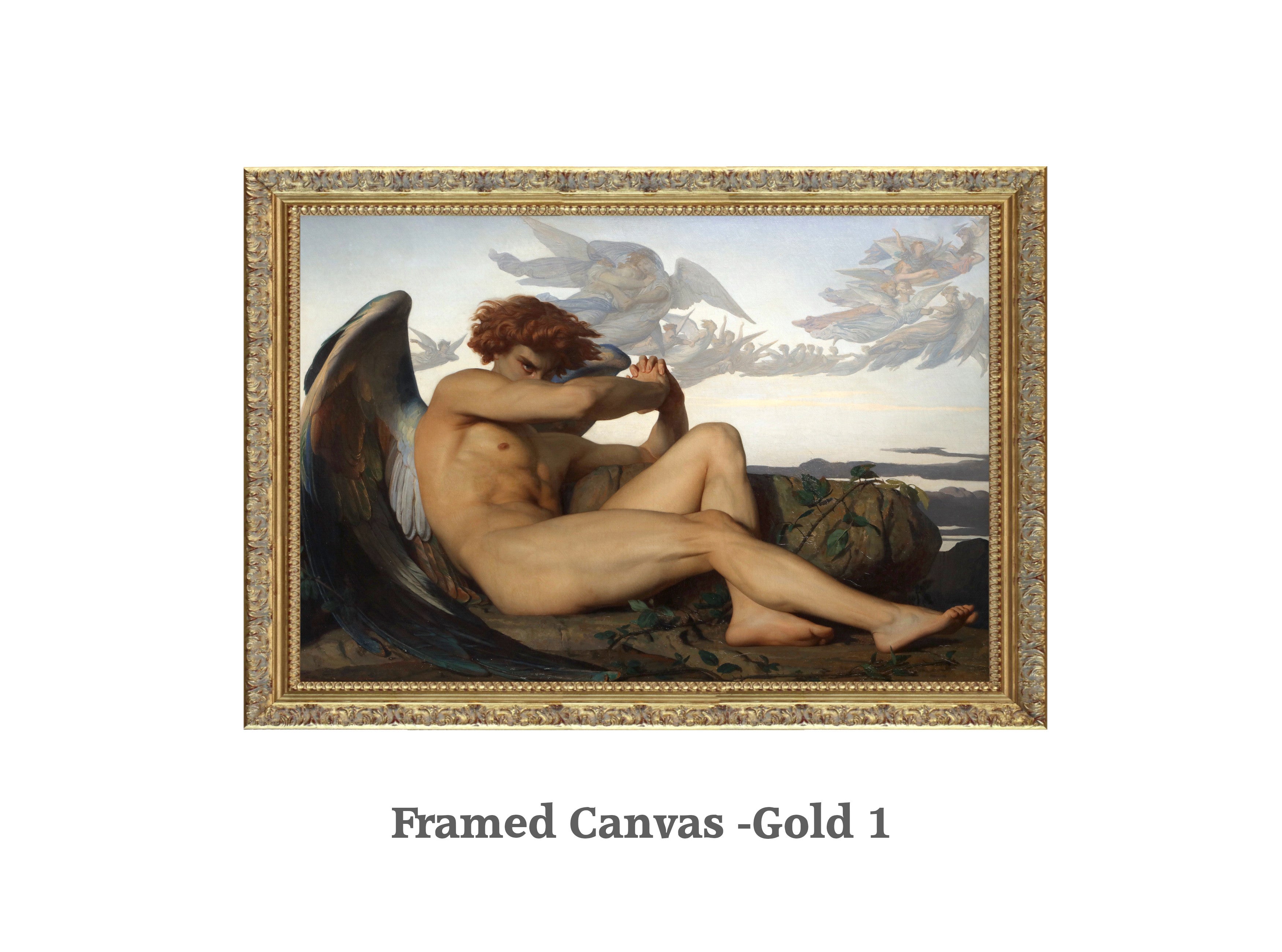

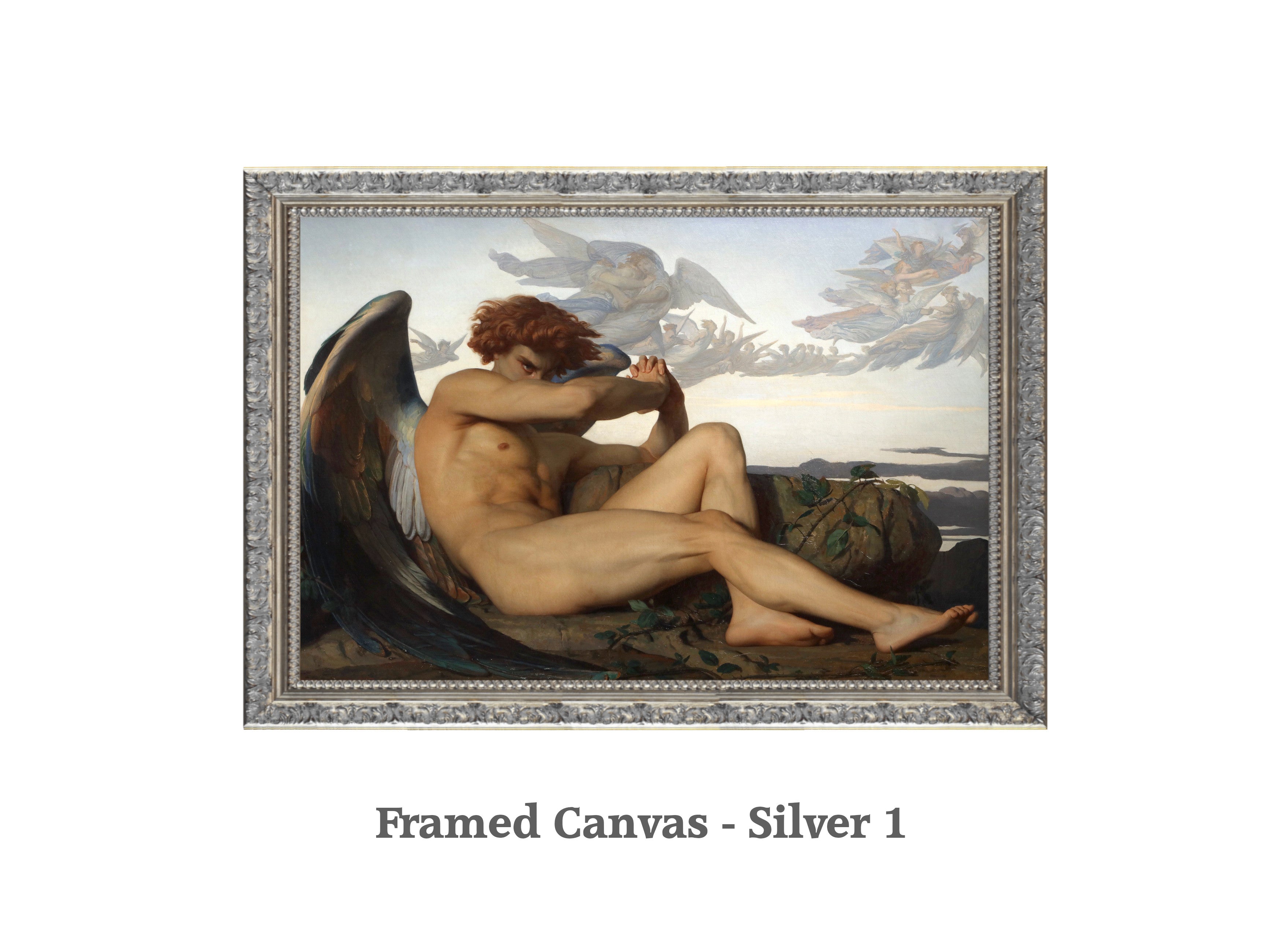

These and many more exapmles of paintings of the Crucifixion are available as fine art prints and canvas reproductions in a range of sizes and frame styles.

Compassion, William-Adolphe Bouguereau

Ecce Homo Peter Paul Rubens (c.1612)

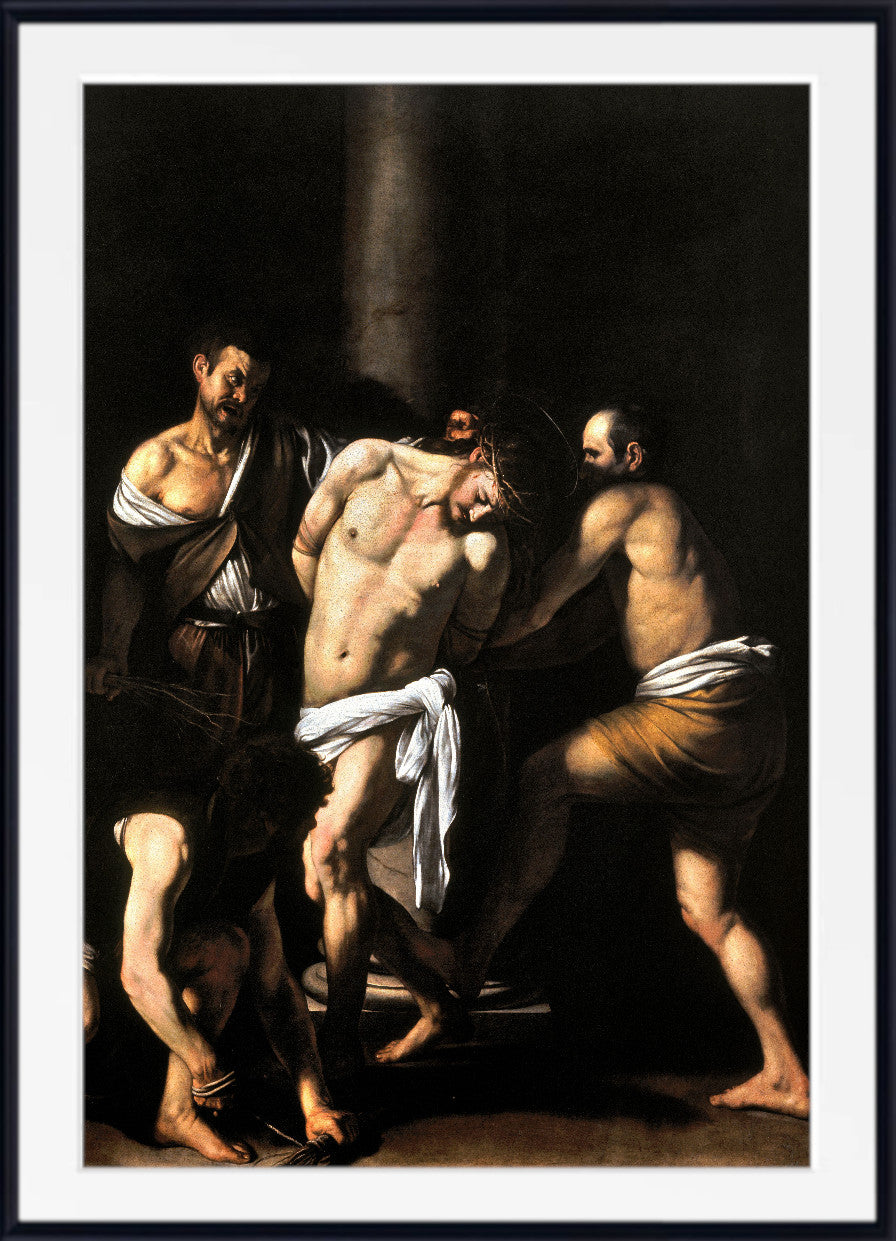

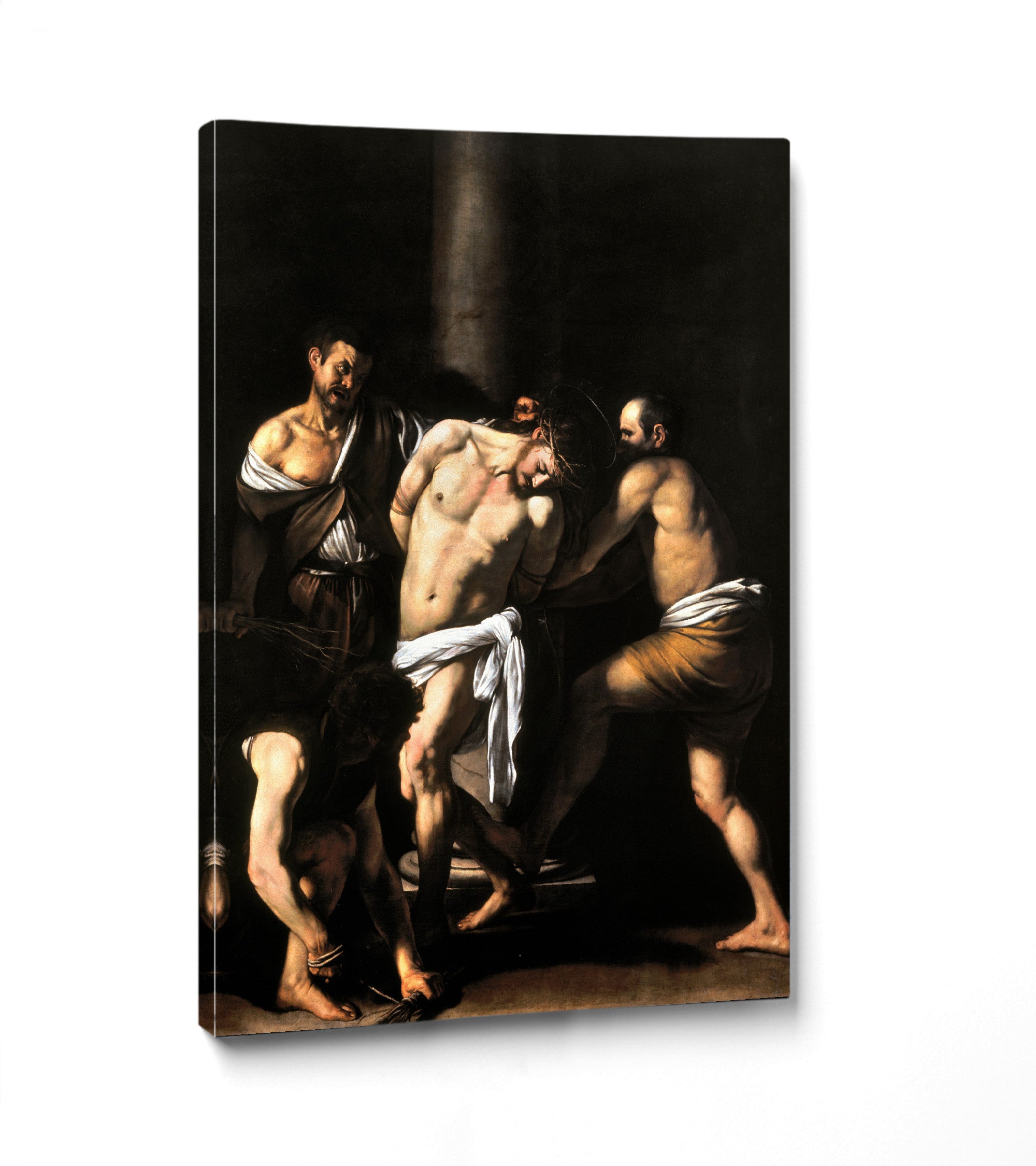

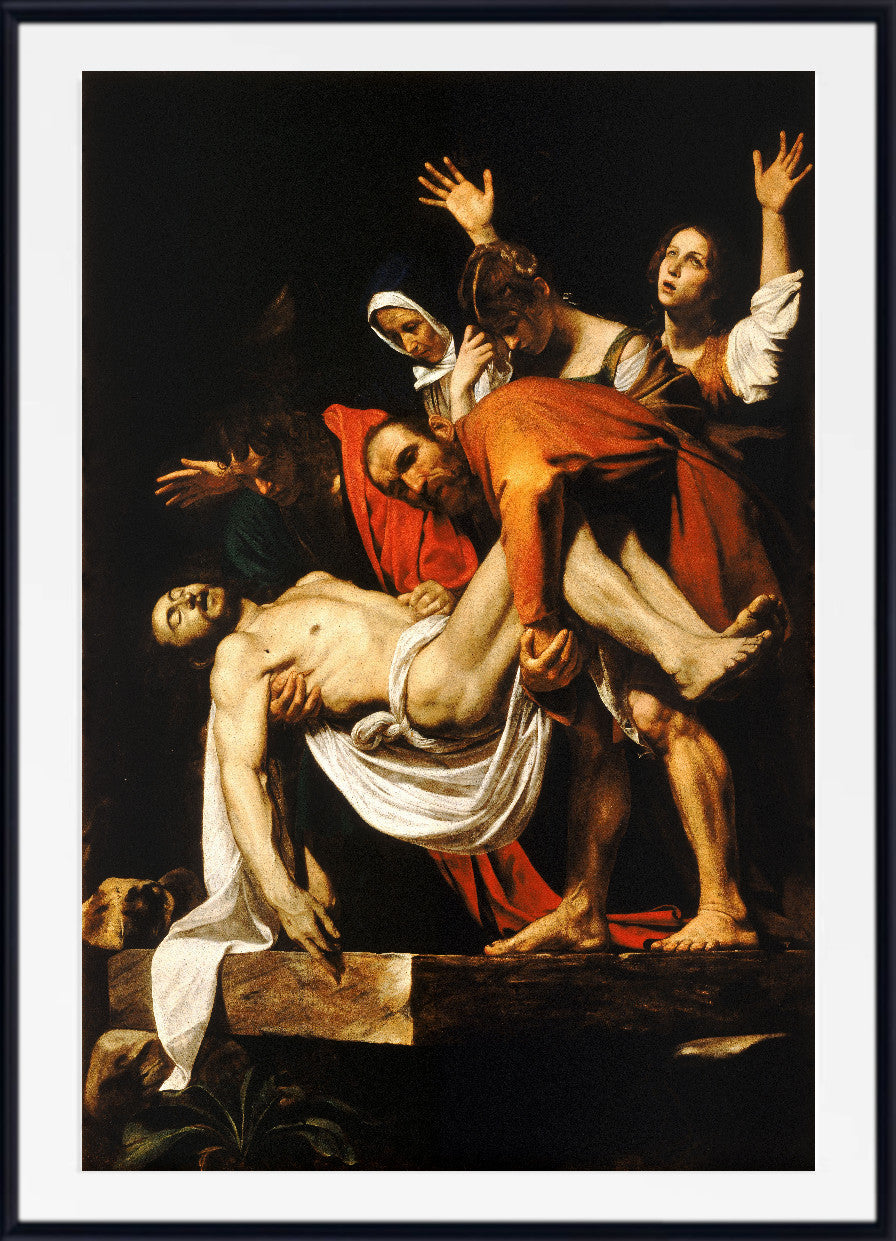

BEHOLD THE MAN

Ecce Homo, (Latin: “Behold the Man”), theme prevalent in western Christian art of the 15th to 17th century, so called after the words of Pontius Pilate to the Jews who demanded the crucifixion of Jesus (John 19:5). Paintings on this theme generally conform to one of two types: devotional images of the head or half-figure of Jesus, or narrative depictions of the judgment hall scene. In either type, the scourged and mocked Christ is shown wearing a crown of thorns and purple robe placed on him by the Roman soldiers. In many examples, his wrists are tied and a rope is knotted around his neck. Scourge marks are frequently emphasized, and his face expresses compassion toward his accusers. In the narrative versions, two guards are often shown supporting the suffering figure while Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea, gestures toward Christ, illustrating his words.

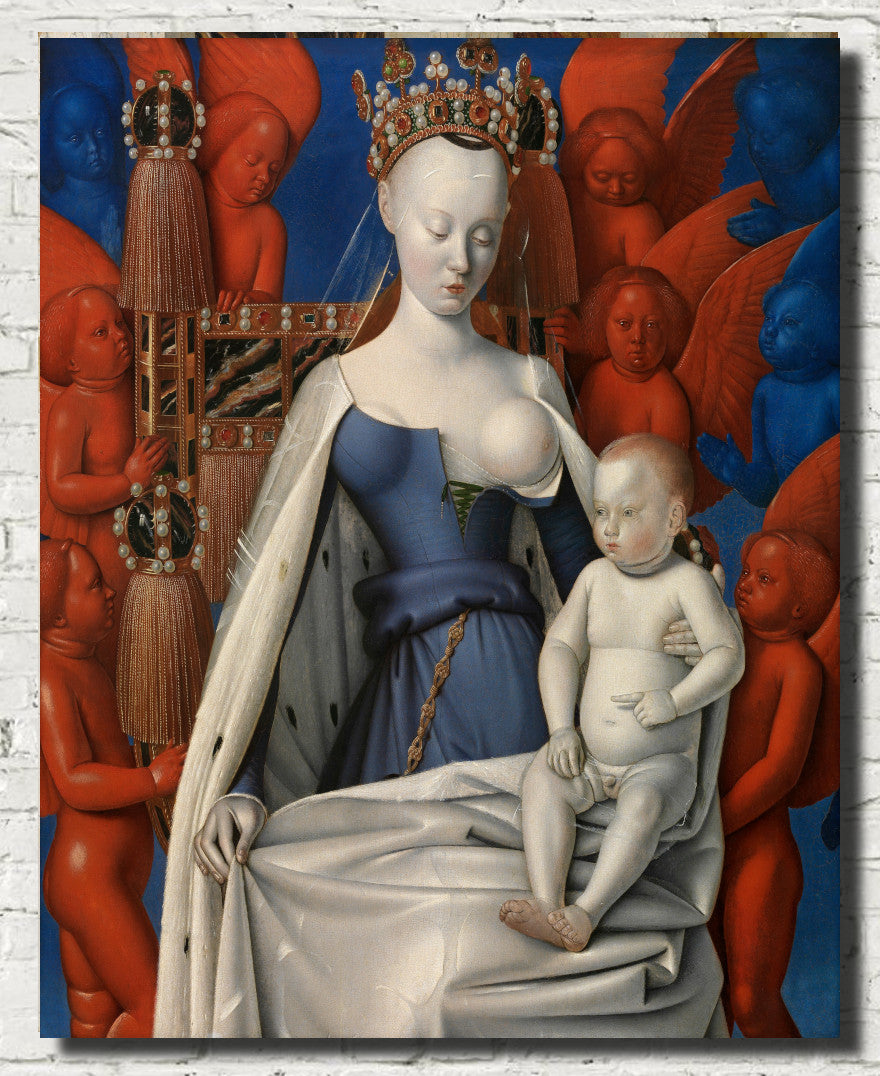

THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION PAINTINGS

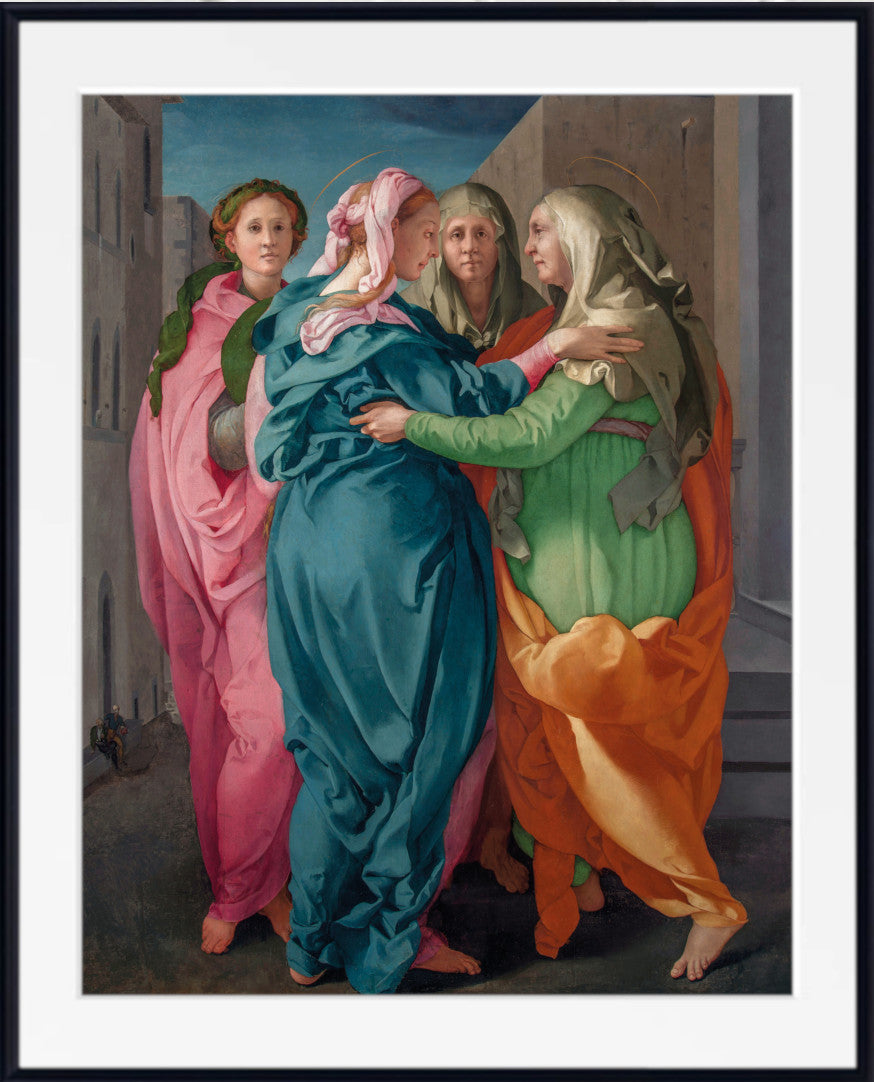

The theme of the Immaculate Conception has been used in art predominantly by Italian and Hispanic artists, perhaps due to these region's strong connections to the Christian Faith. They were also inevitably more frequent during the Renaissance and Baroque periods, when religion dominated society and much of the art within that.

The original oil painting is just under two metres tall and represents one of Peter Paul Rubens' finest religious-themed artworks. This Flemish master was one of the true spearheads of the Baroque movement of the 17th century.

The Immaculate Conception refers to the creation of the Virgin Mary, not Christ as some incorrectly assume. Her purity is provided by God, in preparation for the arrival of his son, Jesus Christ. This powerful religious painting holds great significance to Christians around the world and its emotive atmosphere makes it an ideal choice as artistic inspiration.

Immaculate Conception, Peter Paul Rubens c.1628

Saint Francis in Prayer, Caravaggio

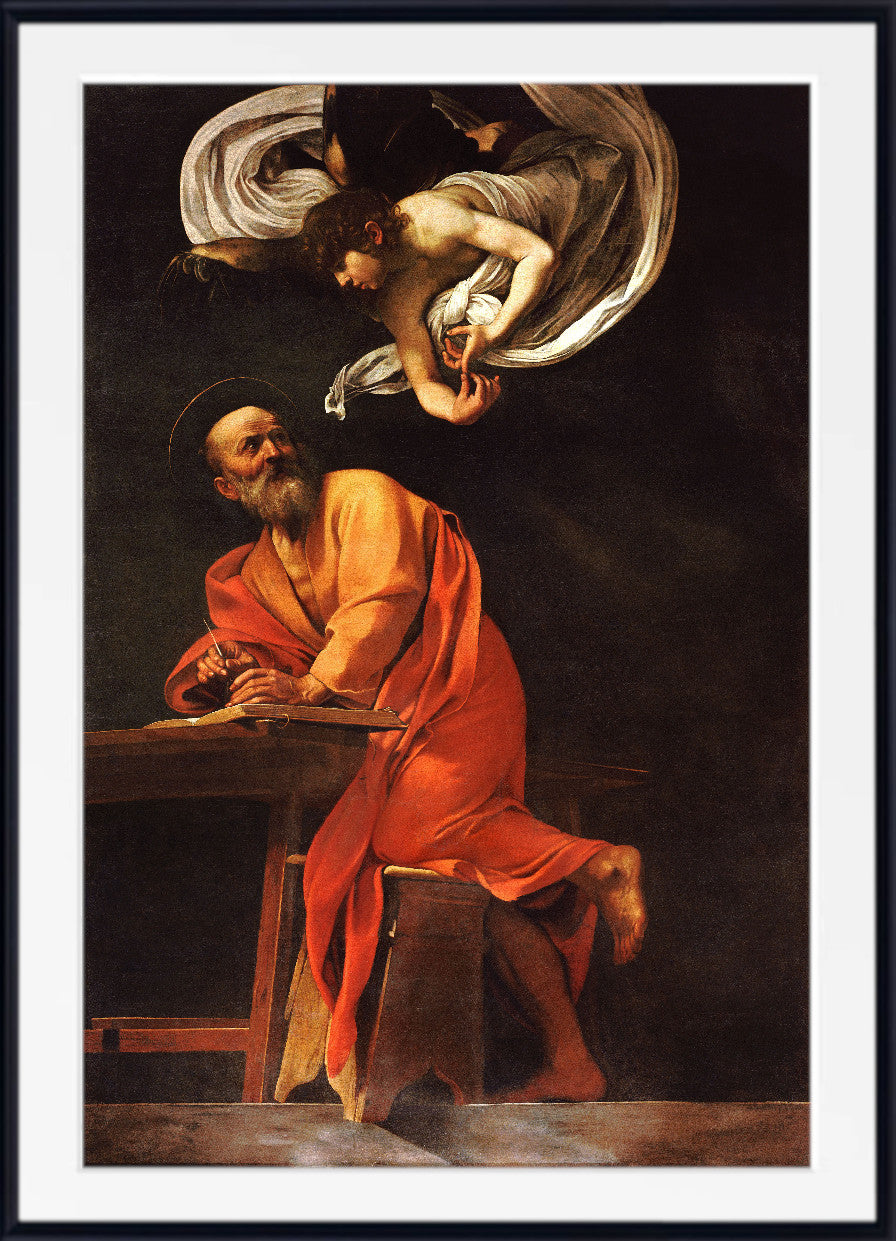

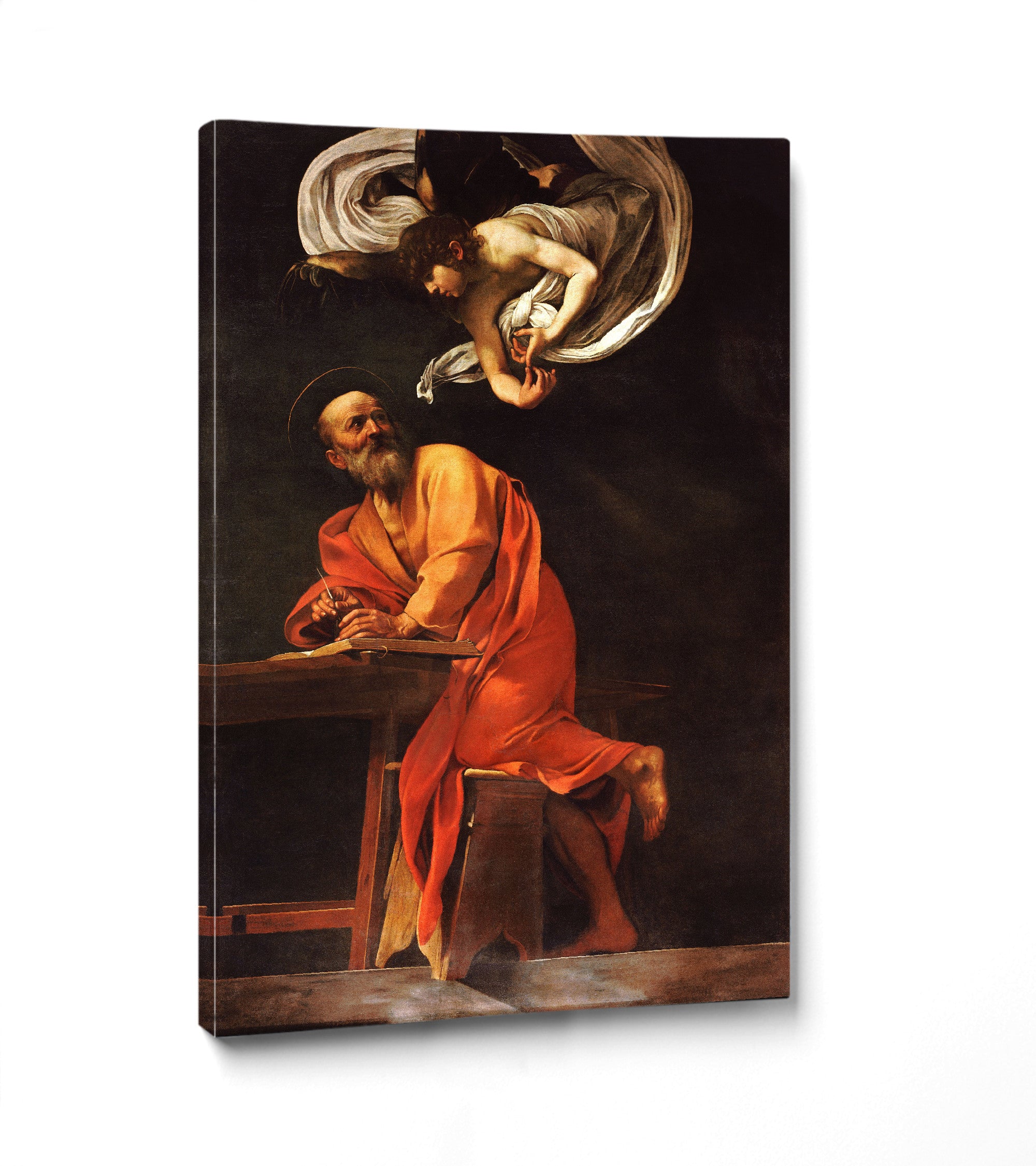

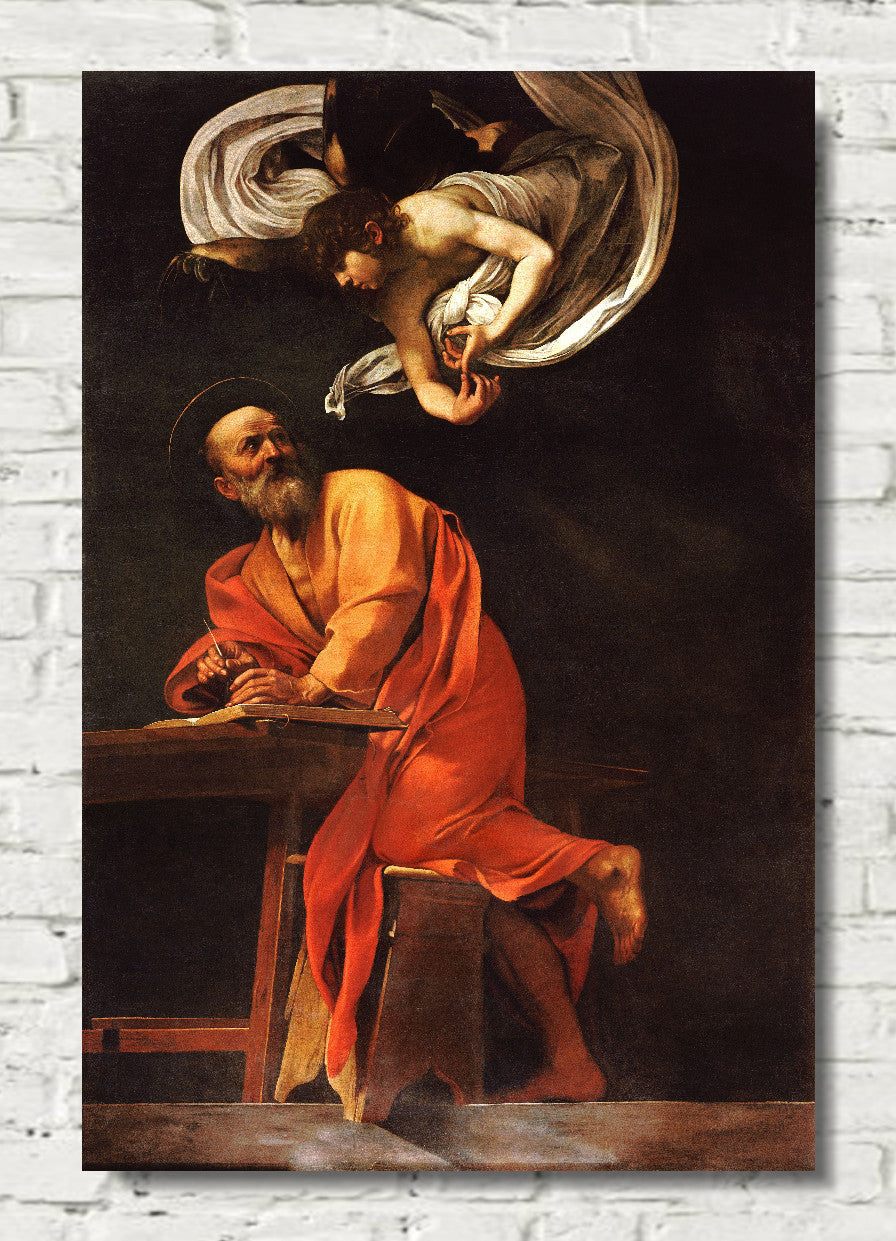

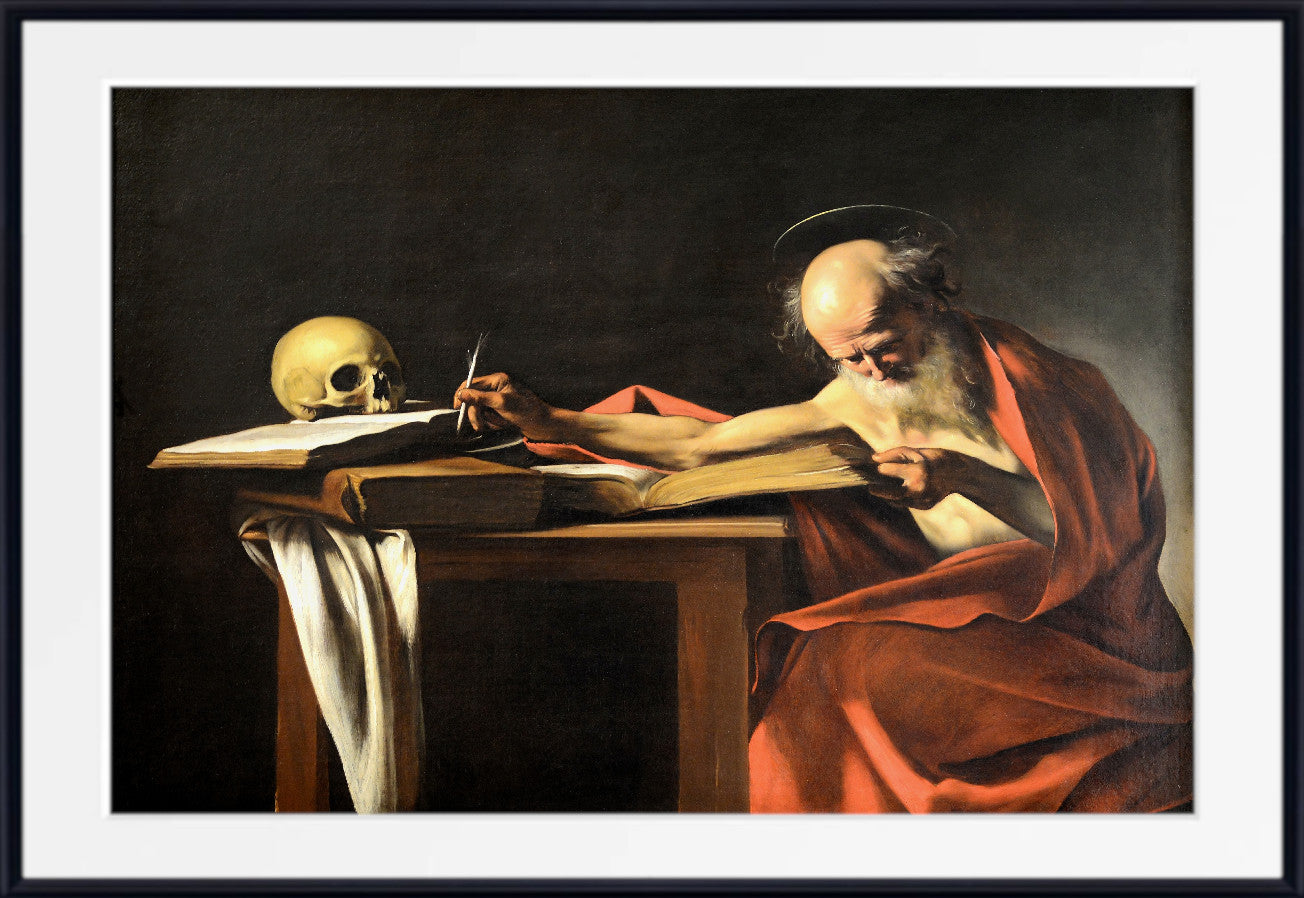

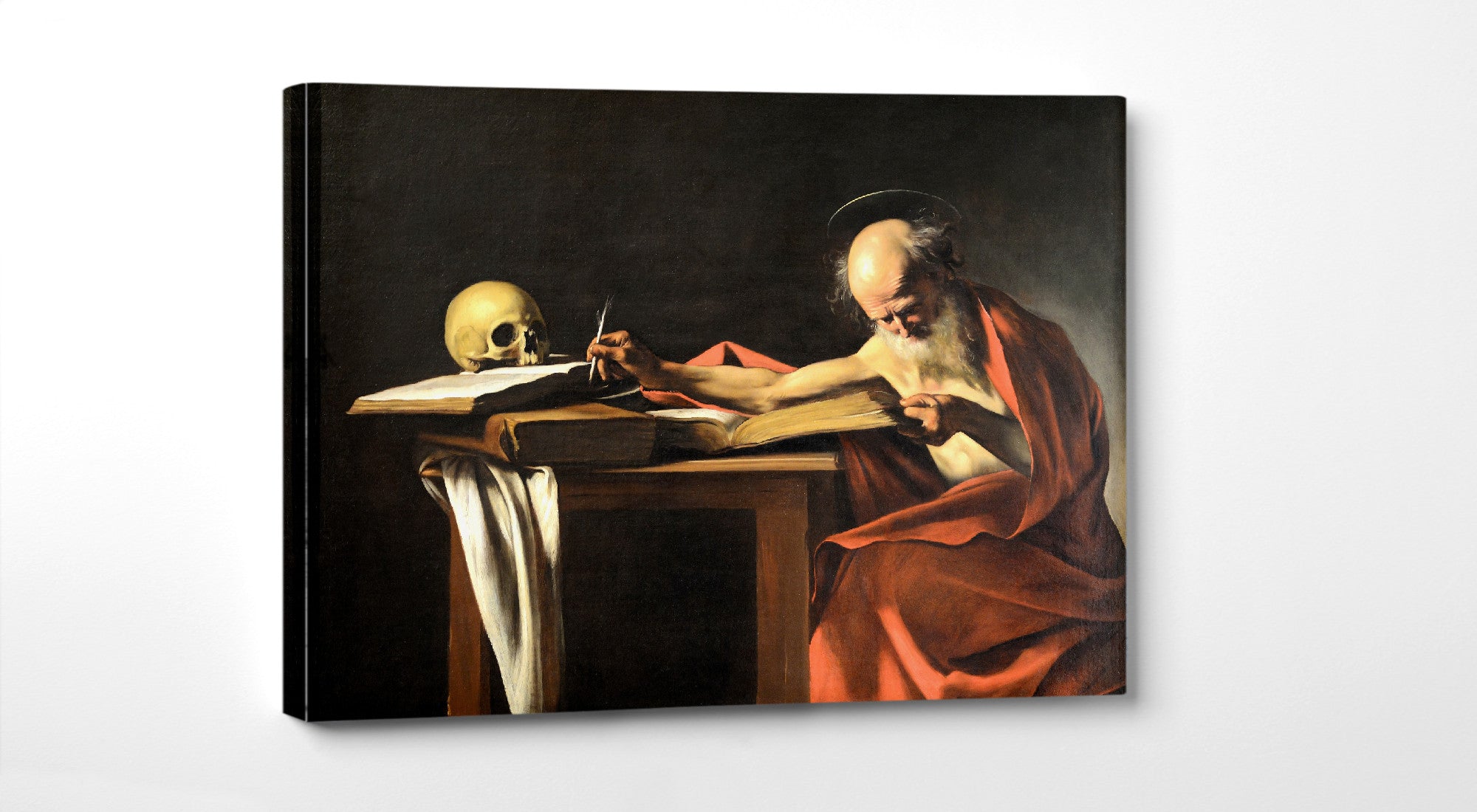

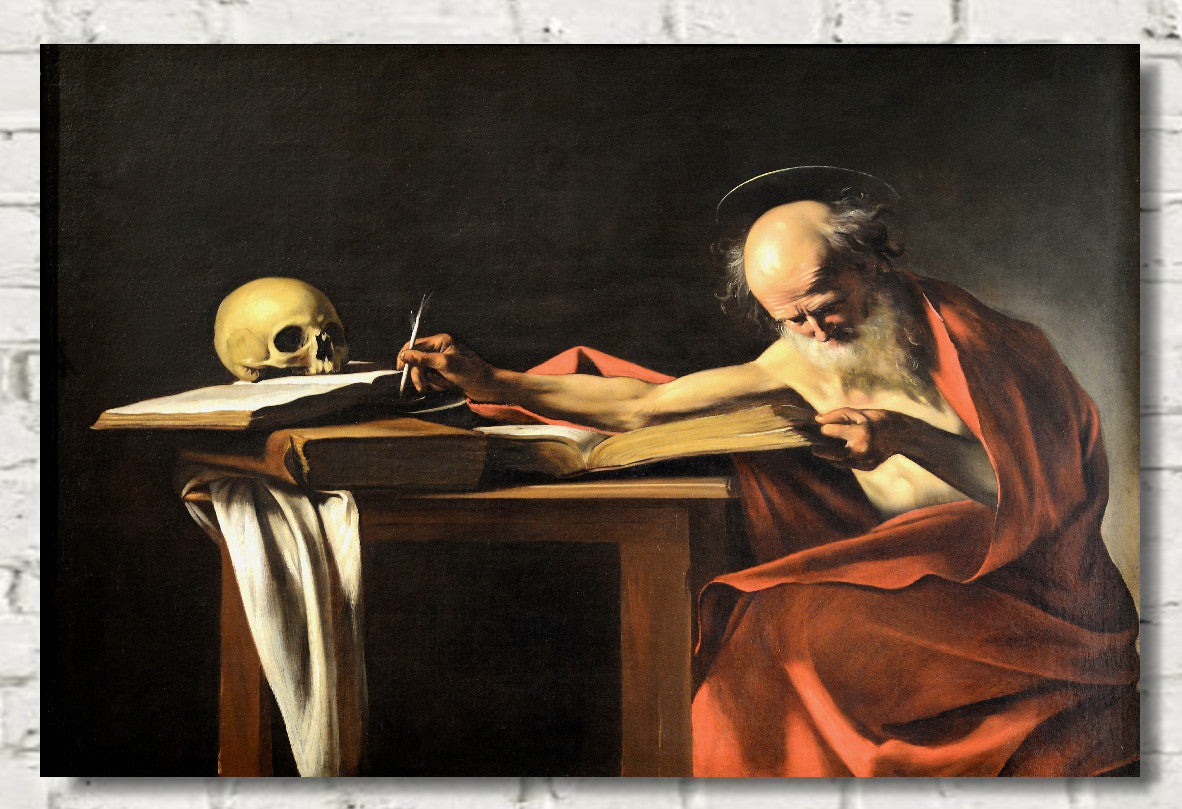

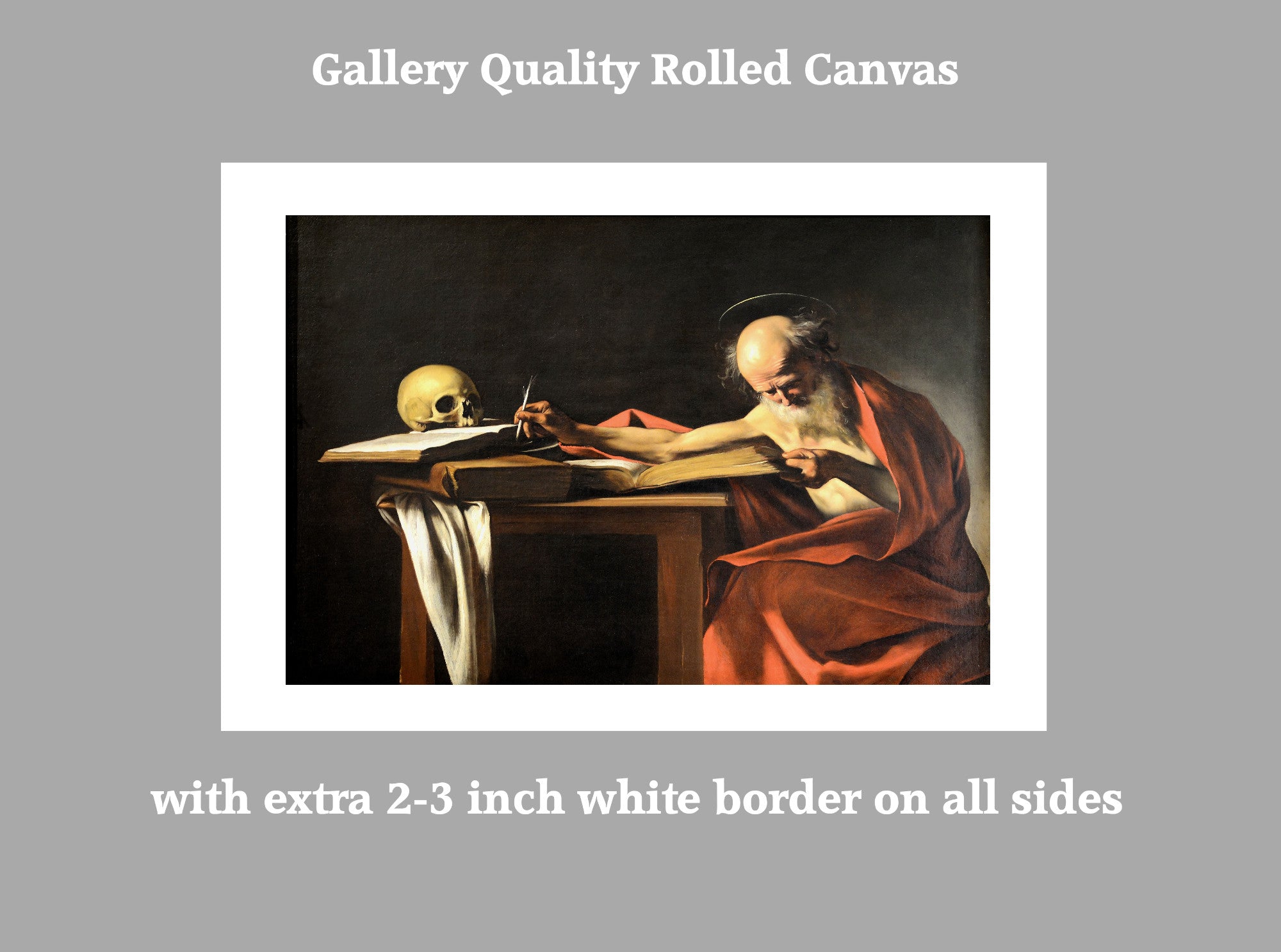

ICONIC IMAGES OF THE SAINTS

Saints are probably some of the most looked-at images in art history and a subject that artists have returned to time and again. Although we live amongst churches, schools and institutions which bear the names of saintly figures we often remain unaware of their stories and the all-important symbols, known as 'attributes', that artists use to identify them. Low literacy rates in the Middle Ages meant that symbolic details in art were of paramount importance to the Church when it came to educating and instructing viewers. By the time of Jacobus de Voragine's widely-read The Golden Legend (1259–1266) (later translated into English by William Caxton in the fifteenth century), a fascination with the lives of saints and a 'cult of relics' flourished across Europe, inciting pilgrims to travel to the enshrined sites of saints. In response, artists adopted specific forms of iconography that made saints quickly identifiable to the layperson.

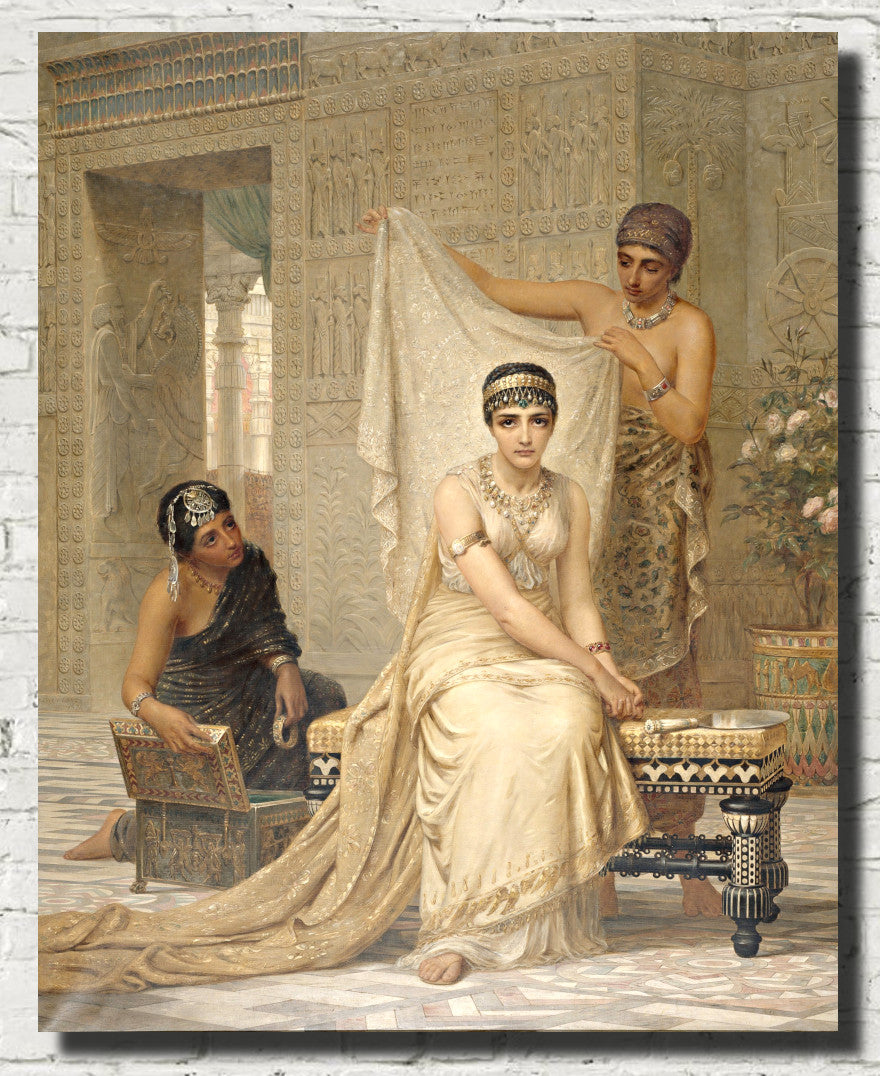

The choice of Christain art has continued to grow in more recent times with works from Fritz von Uhde, Marianne von Werefkin, Frederic Leighton and many others displayed at GalleryThane.