In his own time, Bouguereau was considered to be one of the greatest painters in the world by the Academic art community, and simultaneously he was reviled by the avant-garde. He also gained wide fame in Belgium, Holland, Spain, and in the United States, and commanded high prices. Bouguereau's career was a nearly straight up ascent with hardly a setback. To many, he epitomized taste and refinement, and a respect for tradition.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau was born in La Rochelle, France on November 30, 1825, into a family of wine and olive oil merchants. He seemed destined to join the family business but for the intervention of his uncle Eugene, a curate, who taught him classical and biblical subjects, and arranged for Bouguereau to go to high school. Bouguereau showed artistic talent early on and his father was convinced by a client to send him to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux, where he won first prize in figure painting for a depiction of Saint Roch. To earn extra money, he designed labels for jams and preserves. Through his uncle, Bouguereau was given a commission to paint portraits of parishioners, and when his aunt matched the sum he earned, Bouguereau went to Paris and became a student at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. To supplement his formal training in drawing, he attended anatomical dissections and studied historical costumes and archeology. He was admitted to the studio of Franccois-Edouard Picot, where he studied painting in the academic style. Academic painting placed the highest status on historical and mythological subjects and Bouguereau won the coveted Prix de Rome in 1850, with his Zenobia Found by Shepherds on the Banks of the Araxes. His reward was a stay at the Villa Medici in Rome, Italy, where in addition to formal lessons he was able to study first-hand the Renaissance artists and their masterpieces. Bouguereau, completely in tune with the traditional Academic style, exhibited at the annual exhibitions of the Paris Salon for his entire working life.

Selected Artworks of Bouguereau

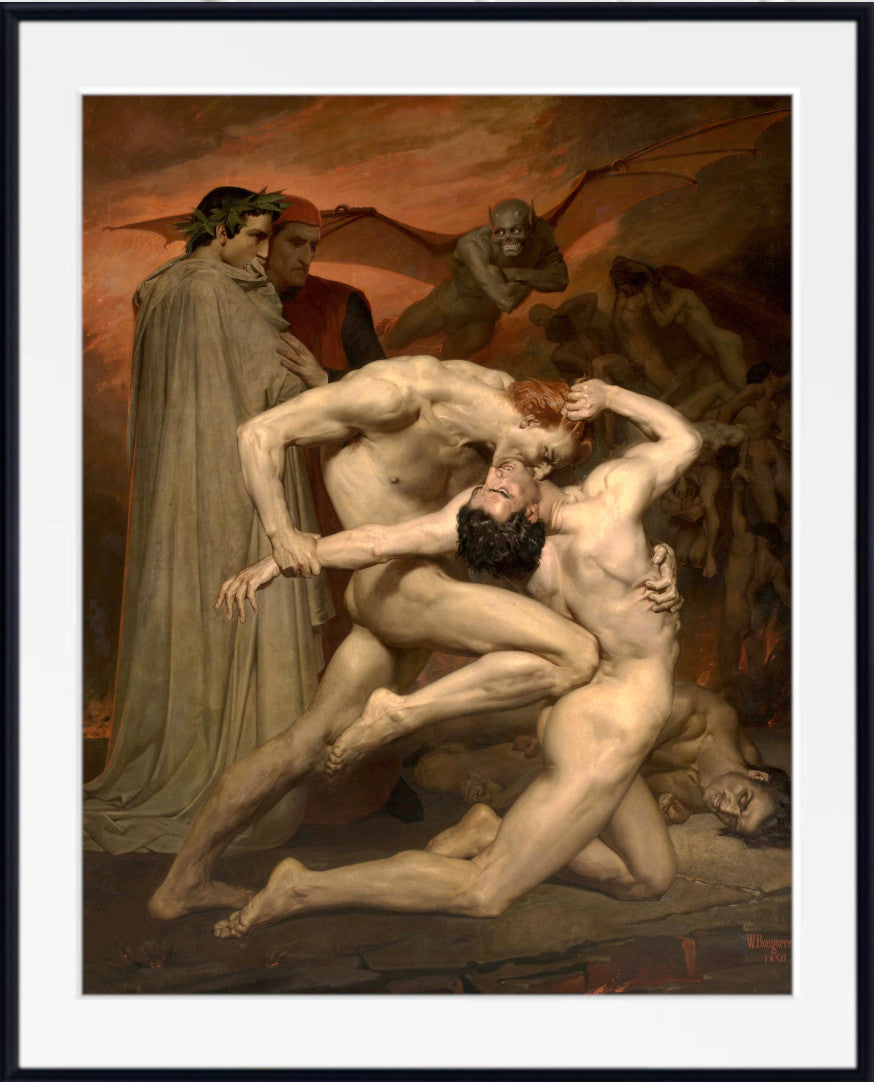

Dante and Virgil in Hell

Bouguereau submitted this atypically macabre work to the Salon of 1850, at a time when he was just establishing himself as an Academic painter. The work garnered significant critical praise, including from the writer Théophile Gautier, who remarked on Bouguereau's attention to musculature and narrative drama. Through his studies at the École des Beaux-Arts, Bouguereau had encountered the works of the great Neoclassical painters, and had absorbed a contemporary fashion for dark subjects from medieval literature. At this early point in his career, he was also concerned with showing off his technical prowess, by capturing unusually strained nude poses. Bouguereau would not return to Dante, soon discovering that - in his own words - "the horrible, the frenzied, the heroic does not pay", and that the public preferred Venuses and Cupids.

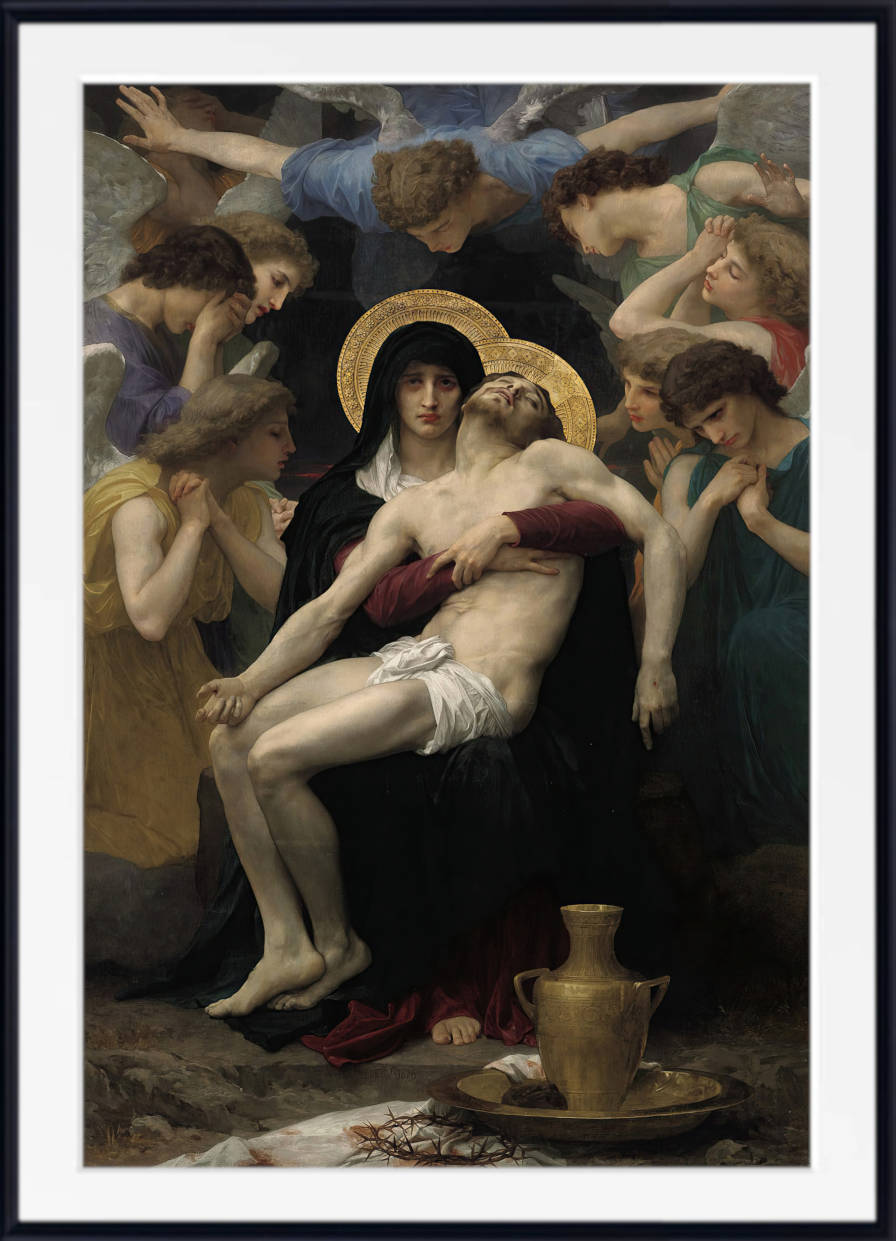

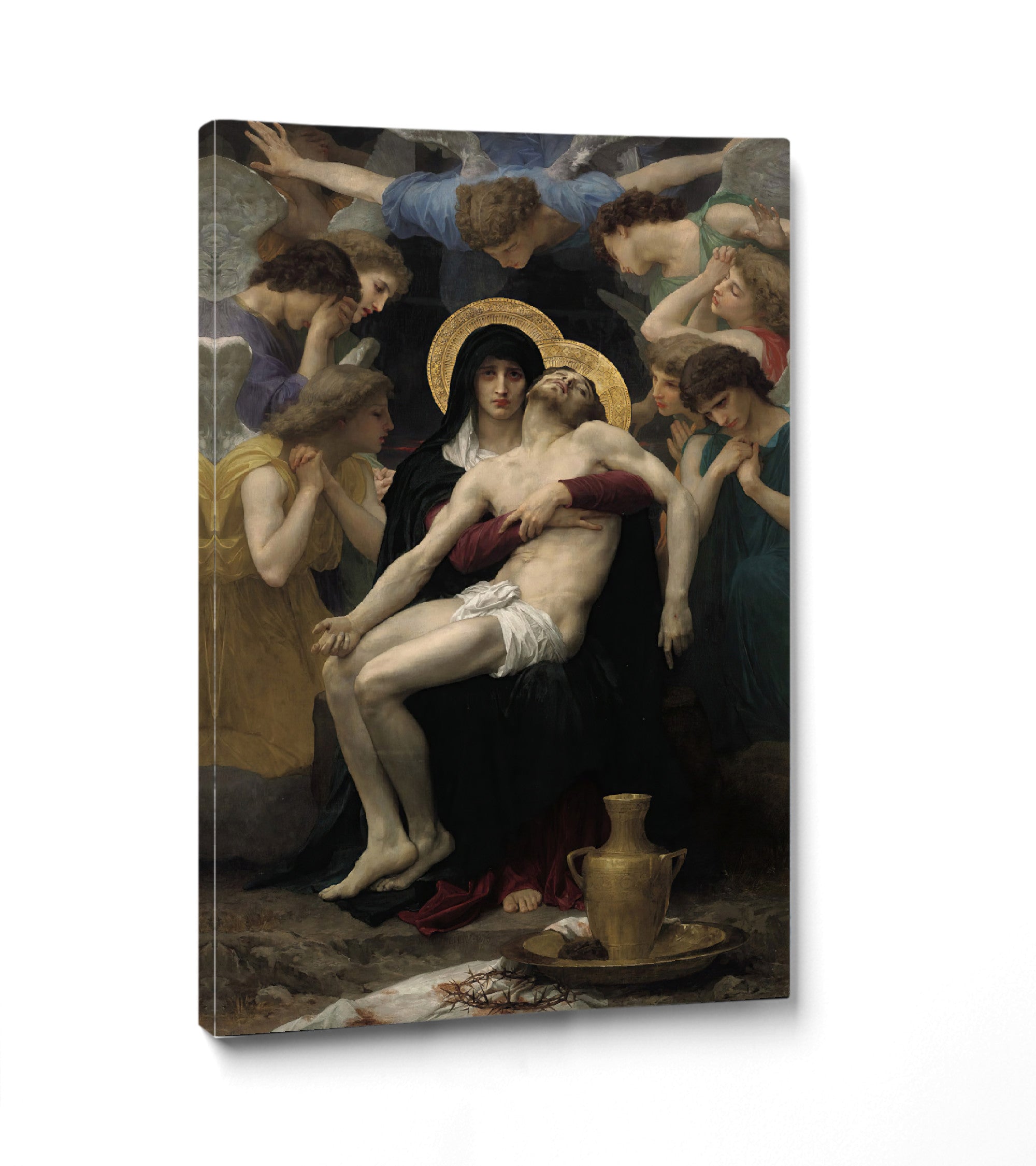

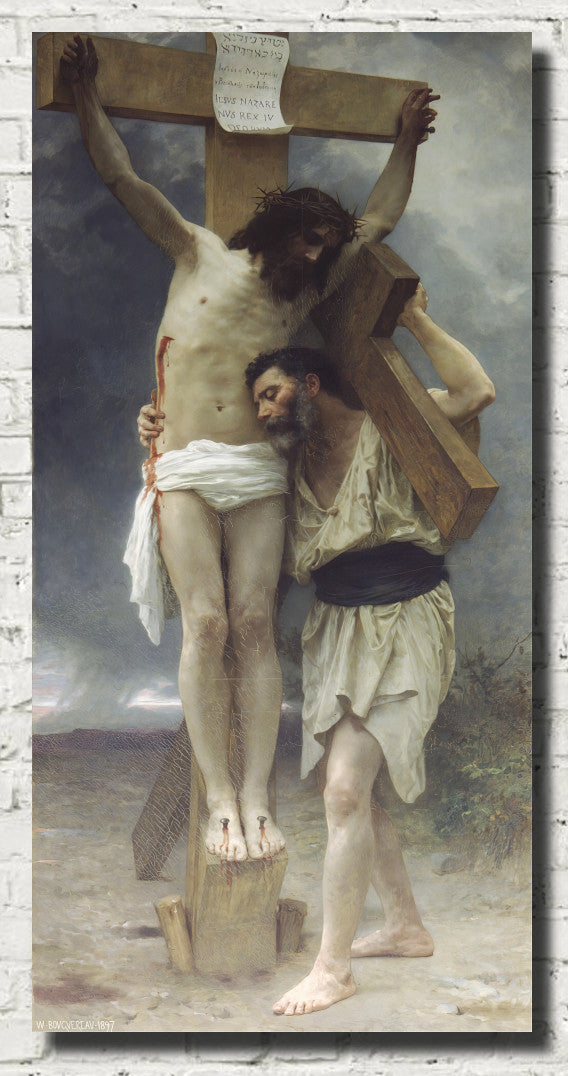

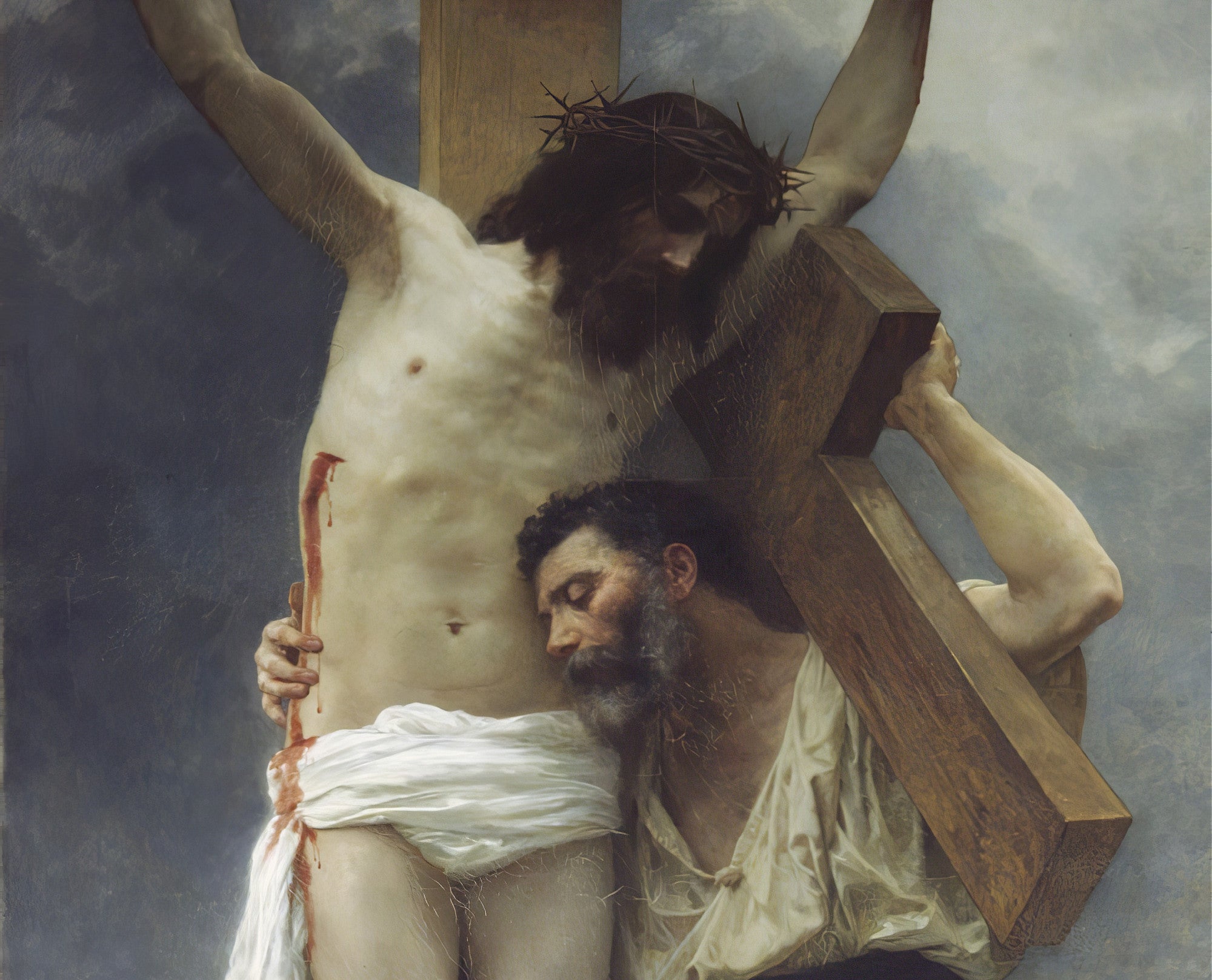

Pieta

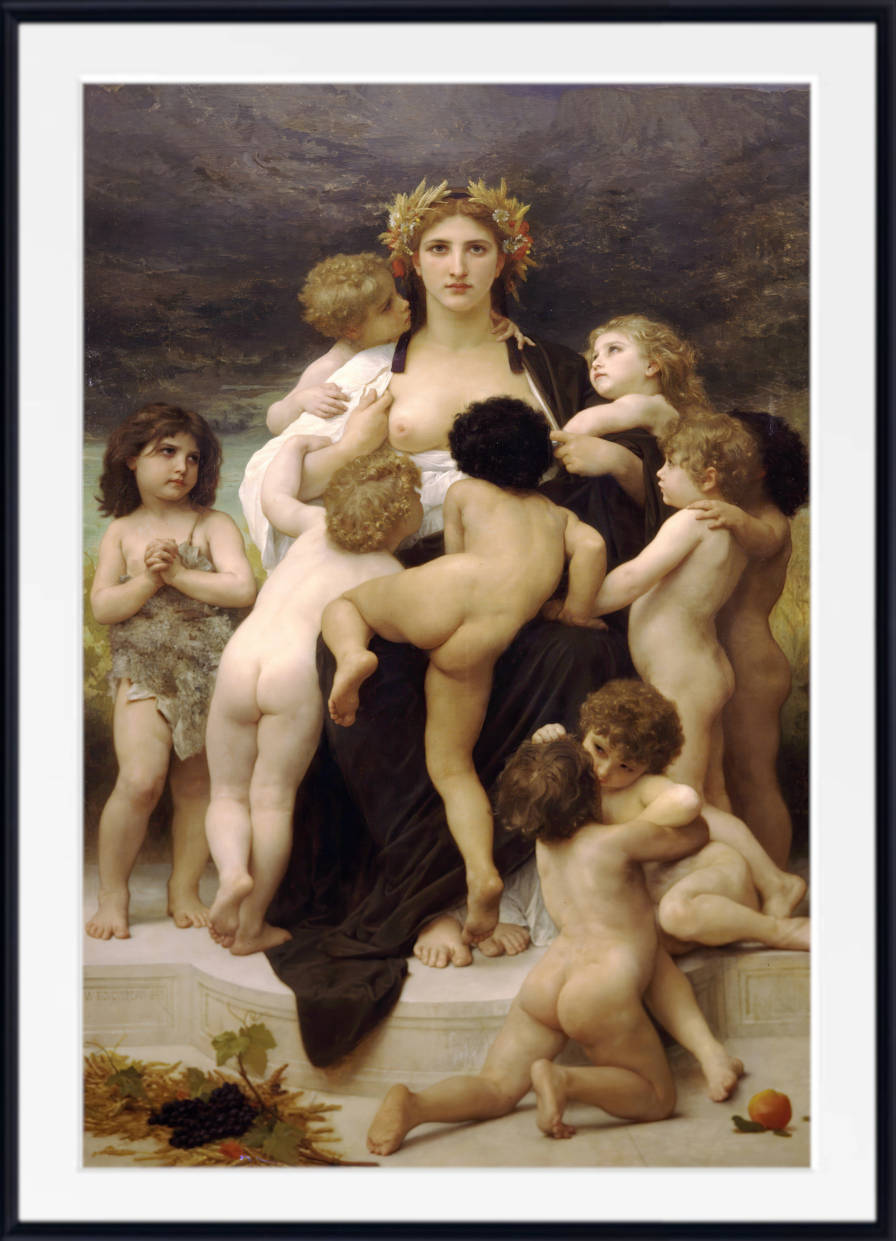

In Bouguereau's interpretation of a famous origin narrative from Roman mythology, Venus, the goddess of love and beauty, emerges from sea-foam standing on a shell, traversing the water to reach land. A flock of nymphs, tritons, and putti surround her in admiration while, in a take on the classic contrapposto stance of Venus Anadyomene from antiquity, the goddess accentuates the curves of her body in alternate directions, while adjusting her hair. Cool pastel colors evoke the dewy atmosphere of the marine world. For this composition, Bouguereau drew inspiration from Renaissance masterworks such as Raphael's The Triumph of Galatea (c. 1514), with its encircling halo of cherubs, and Sandro Botticelli's seductive Birth of Venus (1486), both of which Bouguereau had studied in Italy during his Prix de Rome scholarship. Unlike Raphael and Botticelli's nudes, however, Bouguereau's Venus is captured with a refined naturalism indicating the new artistic tastes of the 1870s, without thereby foregoing Neoclassical artifice. As such, the work rises to the challenge of the late-19th-century Salon painter as described by T.J. Clark: to negotiate the flesh of a modern woman in Naturalist style while clinging to the Academic ideal of "the body as a sign, formal and generalized, meant for a token of composure and fulfillment." In its technical perfection, Bouguereau's Venus appears realistic, yet she remains displaced from individual identity, safely confined to the role of an ideal. This proved to be a successful (and profitable) combination, and Bouguereau received great acclaim for this painting at the 1879 Salon. The strongly erotic tincture also hints at some of Bouguereau's more pragmatic methods for ensuring a buying audience for his work: whereas Botticelli's Venus conceals her bosom enticingly, Bouguereau's invites the viewer to inspect every section of her, unashamed of her nakedness and sensuality.

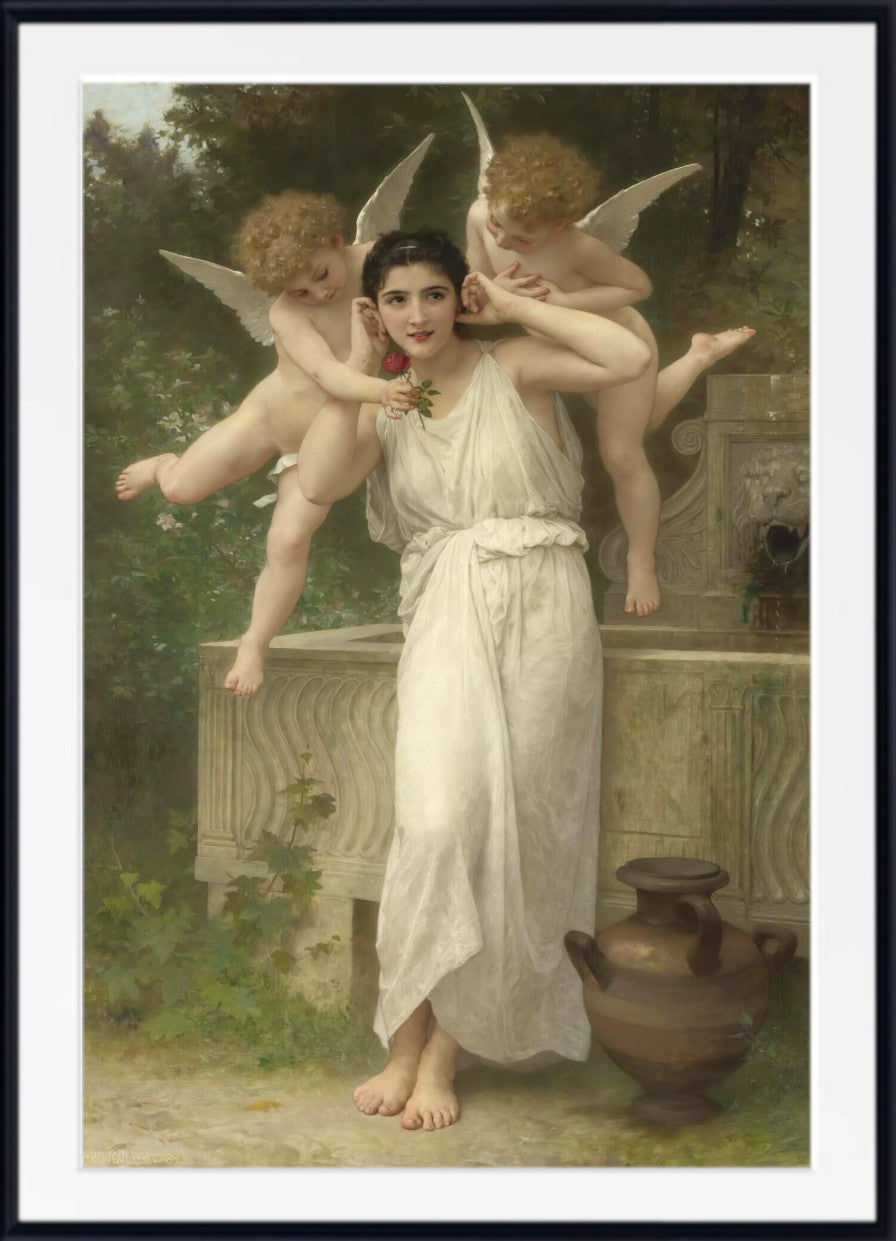

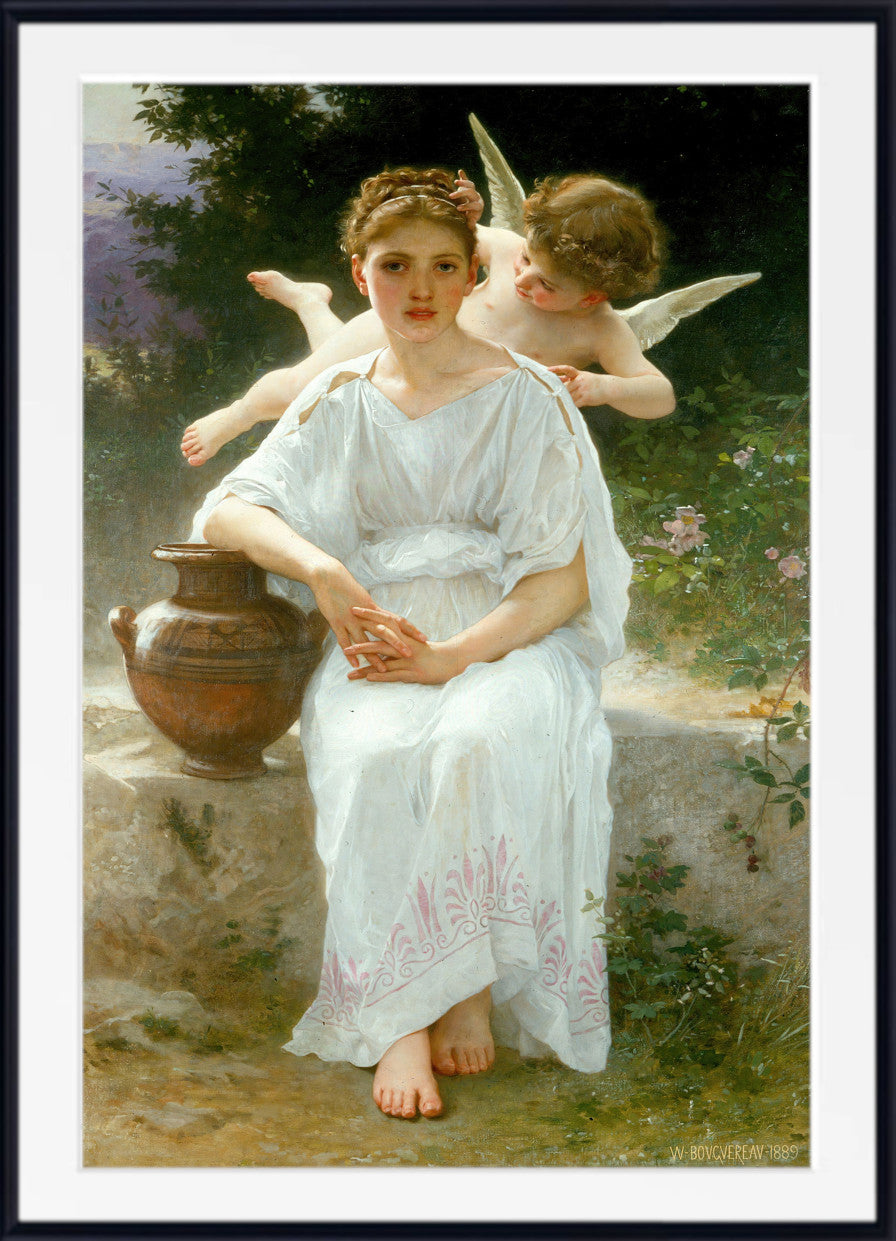

A Young Girl Defending Herself Against Eros

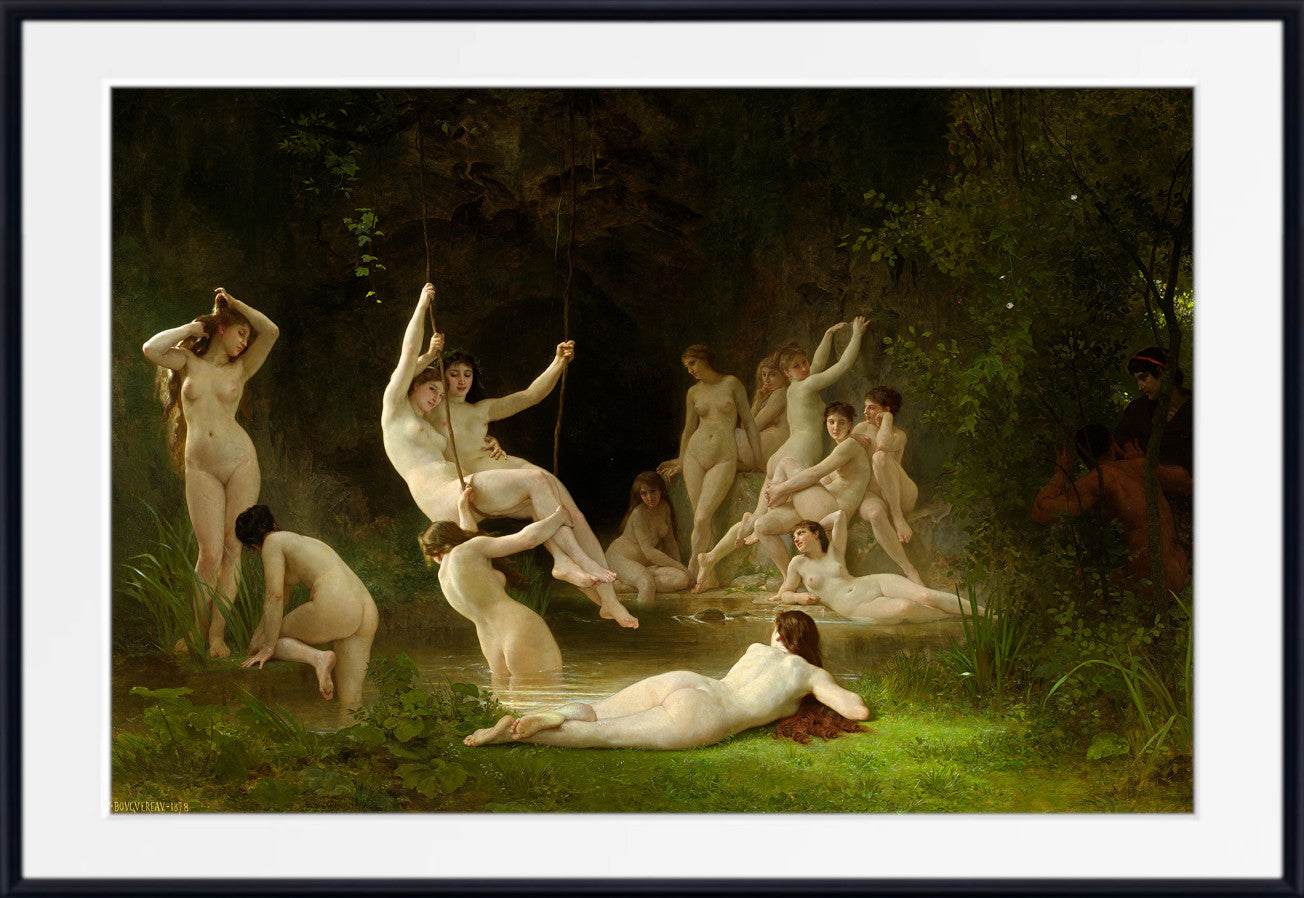

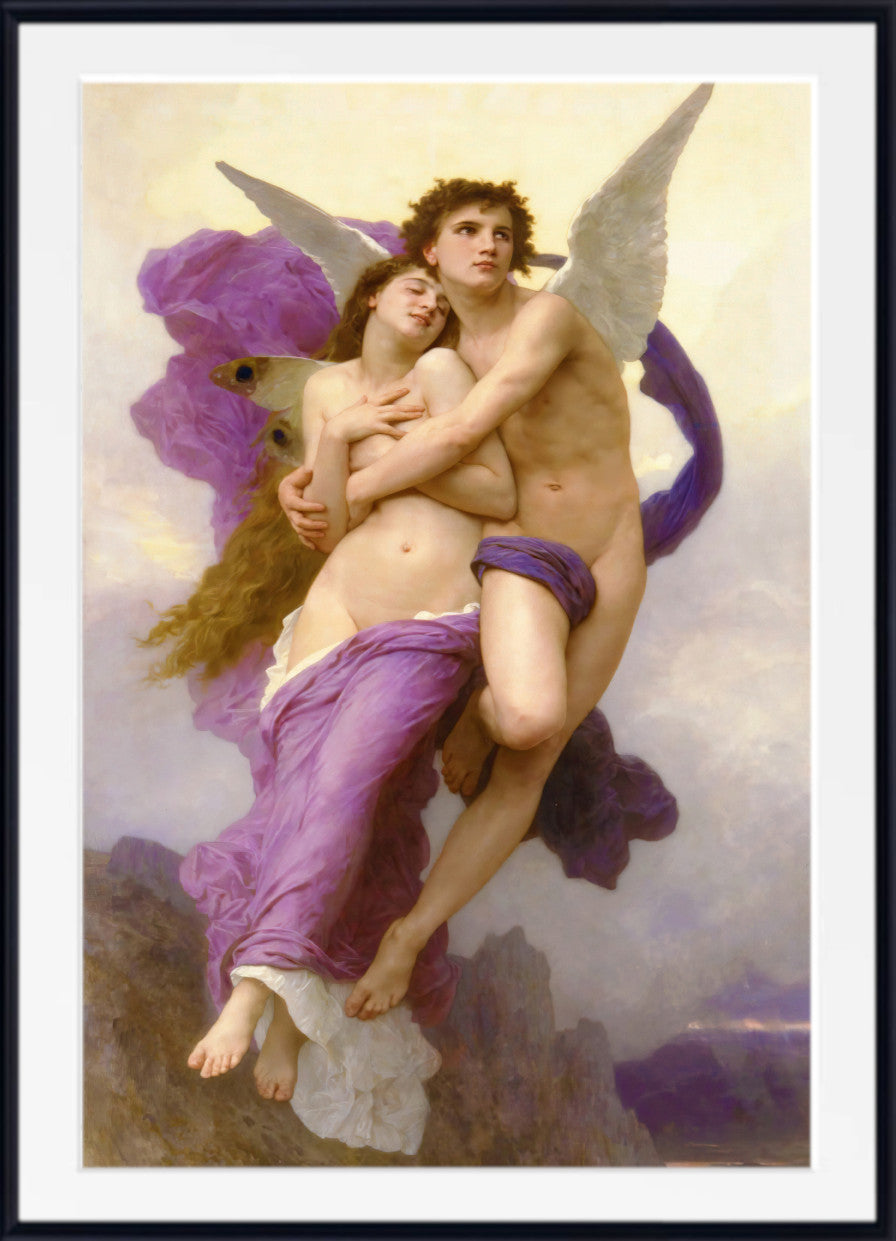

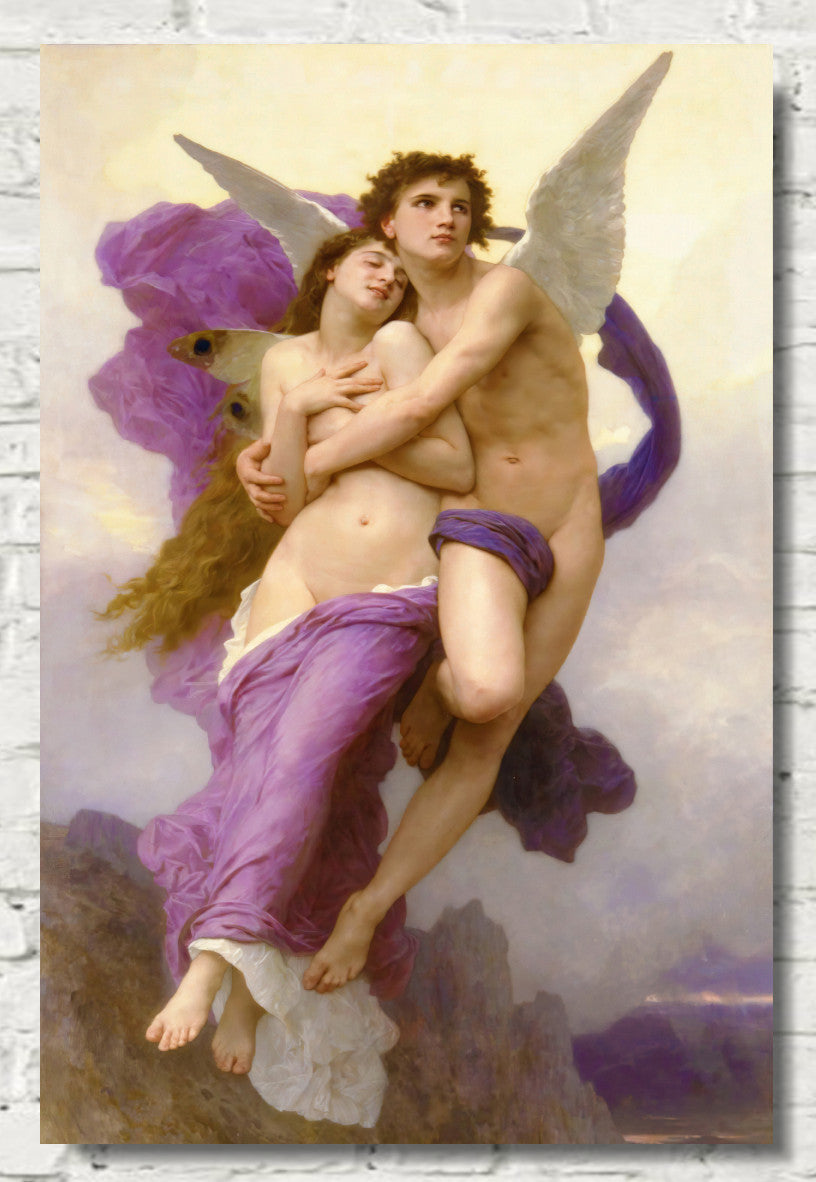

In this, one of Bouguereau's most popular works, a dark-haired maiden - based on one of his most popular models, who appears in several of his other works - pushes away a cherub seeking to pierce her breast with his arrow. The two are locked in a coquettish push-and-pull battle, and the young girl's resistance to Eros seems nominal at best. Her veil slips down to reveal a pert bosom, endowing her innocence with a semi-inadvertent sexuality, granting the painting a voyeuristic appeal. This work is a good example of Bouguereau's erotically-charged classical and mythological tableaux, which sold particularly well with a new market of super-rich buyers in the United States, but which were often the subject of scorn from his Impressionist contemporaries. More than this, Bouguereau acquired the reputation amongst some painters and critics of a lecher, preoccupied with female nudes, and denigrating the legacy of his Renaissance progenitors such as Raphael by producing cheaply eroticized imitations of their work. In stylistic and thematic terms however, the work is not as straightforwardly kitsch as it seemed to his detractors, the landscape based on contemporary France - probably that of the rural south, where Bouguereau had spent many of his formative years - and the painting is thus offering at least a superficially modernizing approach to its subject-matter. Moreover, Bouguereau's mastery of the human form, and of subtle tonal contrasts, is clearly evident.

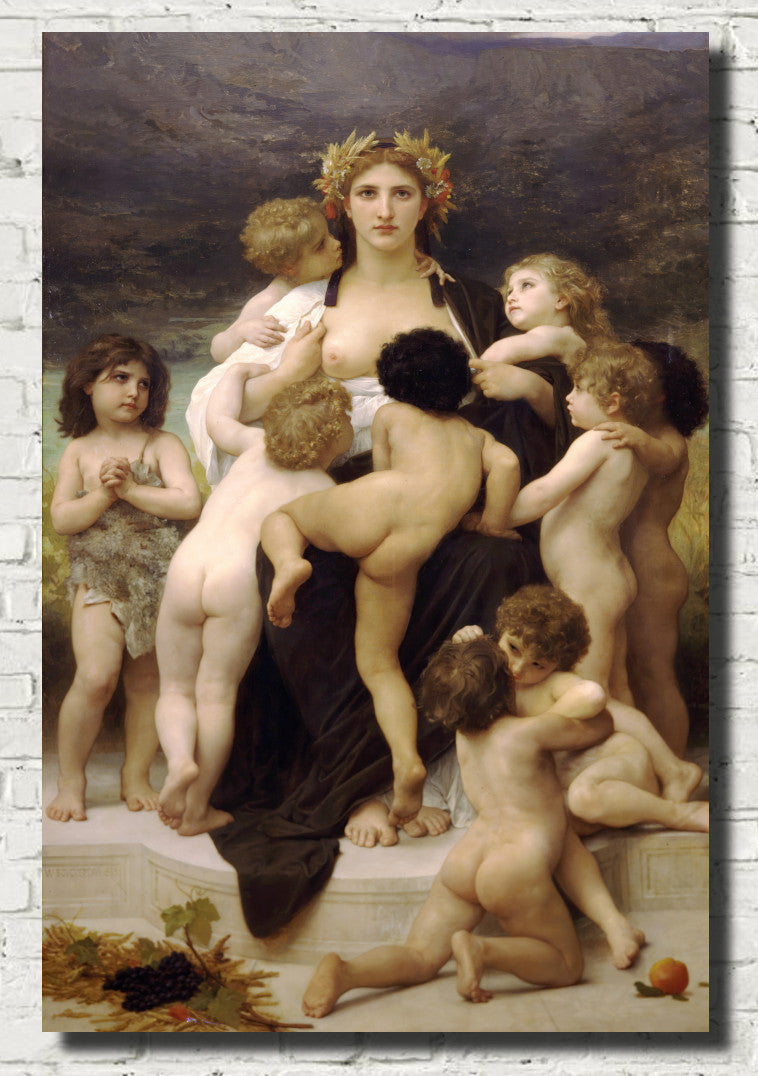

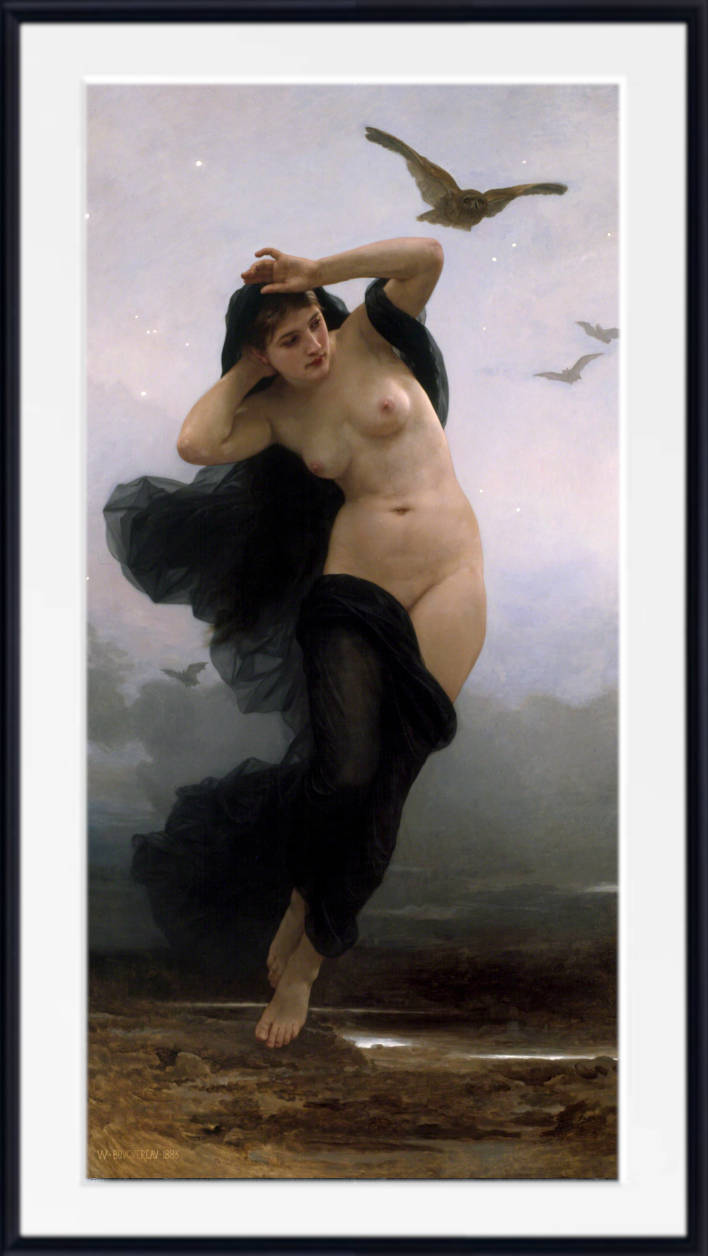

Dawn

Bouguereau's Dawn is the first in a series of four nude studies representing stages of the day, also including paintings entitled Dusk (1882), Night (1883), and Day (1884). In the inaugural work of the series, a nude female figure dances weightlessly on the surface of a pond, reaching over to smell a lily which she cradles gently in her arm. The cool tones of her skin echo the soft colors of early morning, while Bouguereau displays his mastery of dancer's poses by showing her balancing on the very skin of the water. Diaphanous drapery swirls around her, while her suspension in the air, and mirrored reflection, generate a supernatural effect. Bouguereau returned to the marketable motif of the female nude throughout his career, arranging the body in various evocative and illustrative poses, often alluding to myth or literary history. Producing single-figure works such as Dawn allowed him to concentrate on the essential technical crafts of figure-painting: in this case, his mastery of line, and handling of subtle color-contrasts, contribute not only to the sinuous beauty of the figure but also to the atmospheric depiction of early morning. The model's fingers and toes are tinged with pink, a nod to the description of daybreak in Homer's Odyssey as "rosy-fingered dawn, the child of morning". Though the work is not based on any mythological or literary reference beyond this, Bouguereau always endowed his female nudes with a broad sense of classicism and the poetic. Bouguereau's 'times-of-day' series was bought by his regular dealer Adolphe Goupil, who sold the four works in turn to various American collectors. The sale of the series reflects Bouguereau's success with Stateside as well as European art-markets, indicating his unparalleled critical and commercial acclaim during his lifetime.

The Nut Gatherers

Two young girls rest in a grassy clearing, pausing from the task of collecting hazelnuts. One holds a handful of nuts in front of her, while the other seems more interested in playing or sharing a secret. This work is an excellent example of Bouguereau's genre painting - work depicting scenes from everyday life - in which he generally favored the subject of women and girls in agricultural or domestic settings. His nut gatherers are dressed in plain peasant clothes, but appear exceptionally clean and content for members of the rural working poor. By the early 1880s, the official tastes of the Paris Salon were shifting, and the movement of Naturalism was entering the artistic mainstream. Jules Bastien-Lepage's Hay Makers (1877), perhaps the great masterwork of rural Naturalist genre painting, showing two laborers resting after a day's exertion in the fields, had been displayed at the 1878 Salon to great acclaim, and Bouguereau was closely attentive to the shifting moods of the art market. Works such as Nut Gatherers respond to this shift, though his genre paintings display the same idealized polish as his Neoclassical work. Criticisms of Bouguereau as overly sentimental can perhaps be traced to images such as The Nut Gatherers. Nevertheless, his later works are remarkable for their naturalistic precision, and successfully depict themes such as familial relations, quiet contemplation, and harmony with nature. Writing about the artist's view of peasant life for an exhibition catalogue, Mark Steven Walker praises the "heroic attention required to sustain such a vision of perfection in a less than perfect age." The image has certainly proved enduringly popular: sold to the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1952, The Nut Gatherers is cited by the Museum as one of their most popular works.

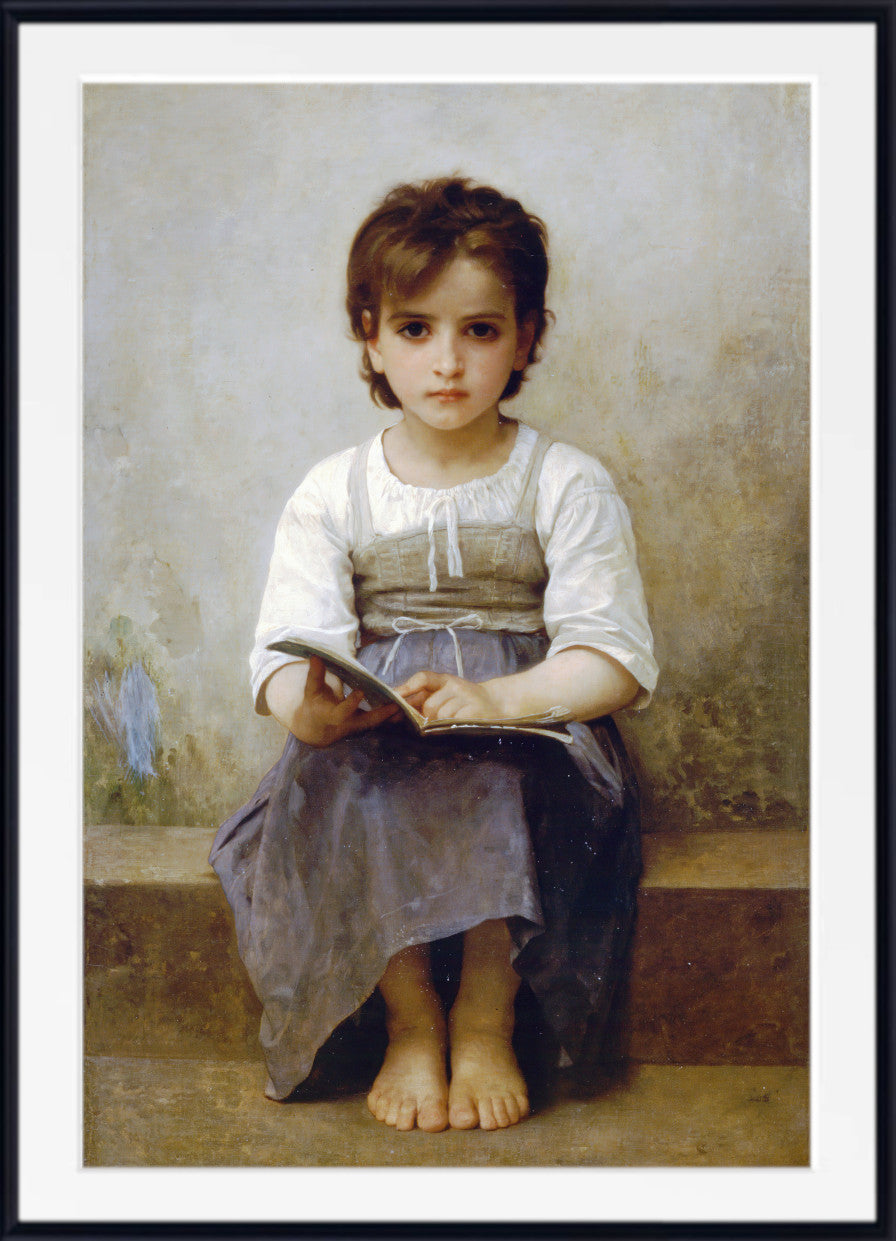

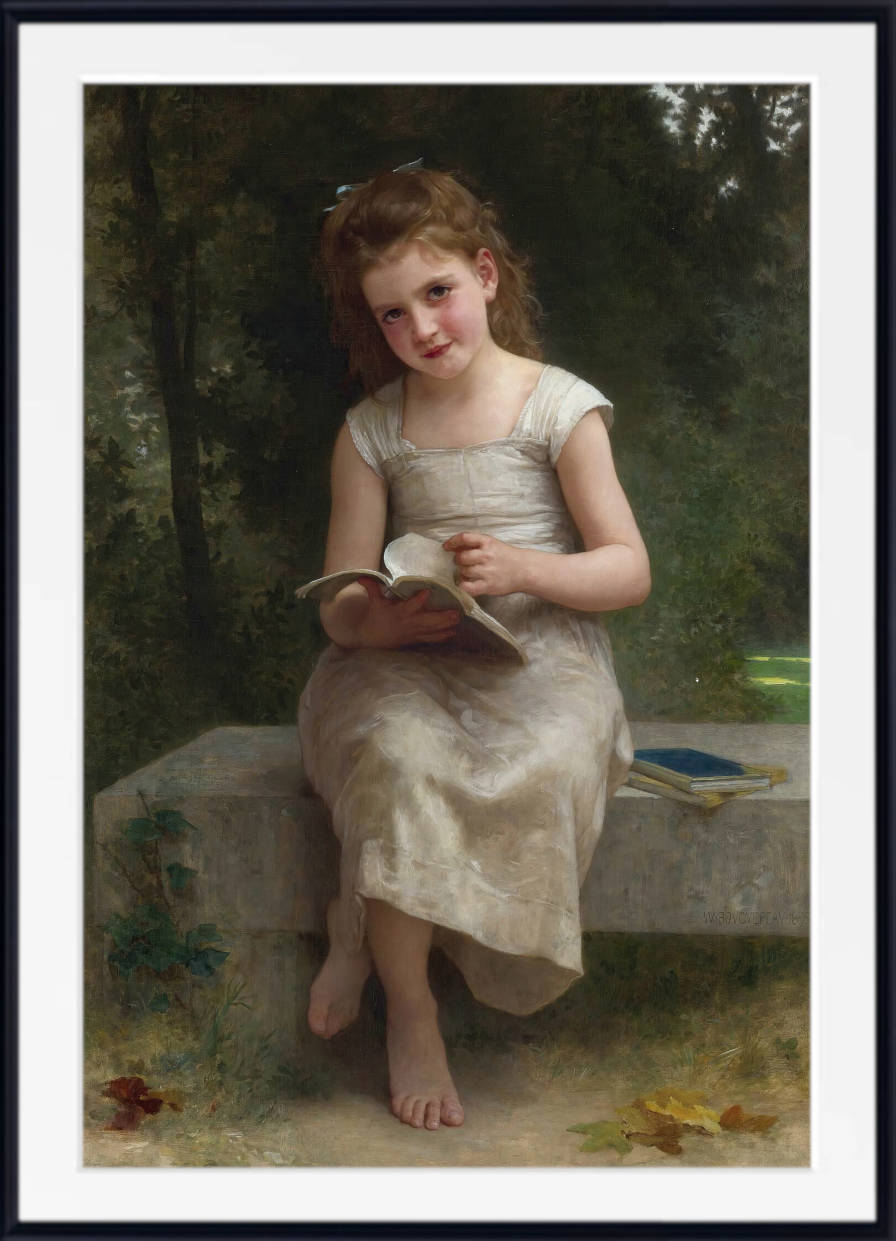

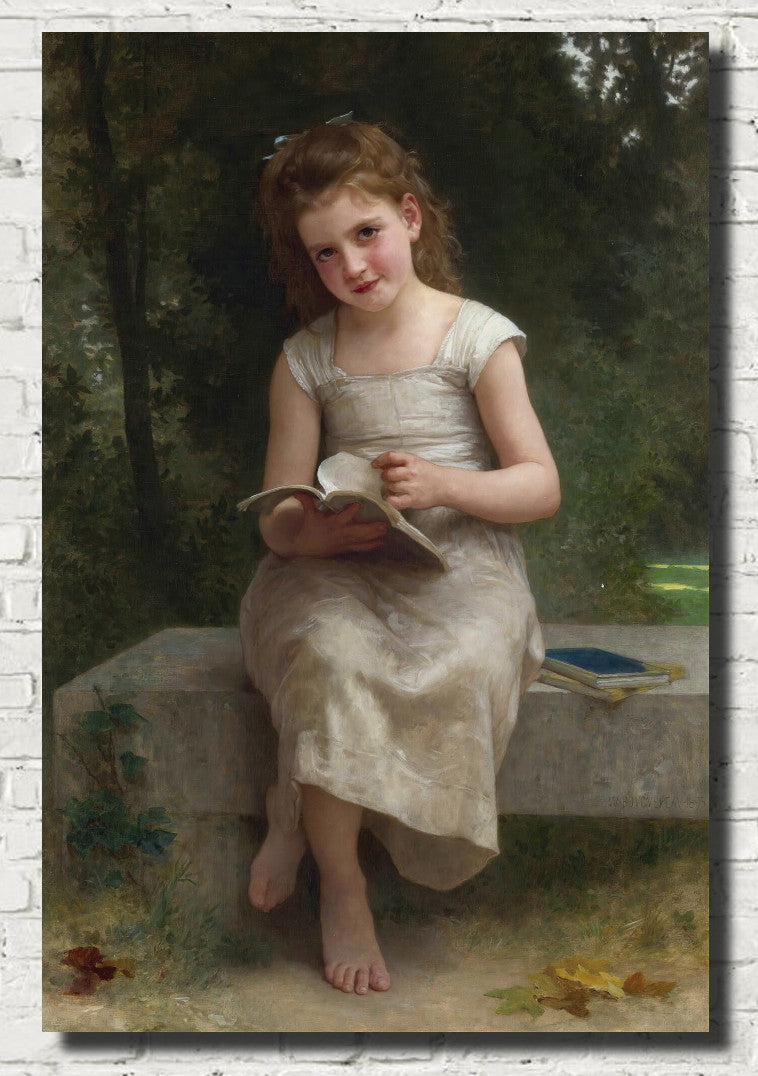

The Young Shepherdess

In Bouguereau's 1885 painting The Young Shepherdess, a girl stands alone at the forefront of an expansive pasture, turning her body to face it with an air of propriety: suitably enough, as the title indicates her responsibility for the flock of sheep it contains. She looks back at the viewer with mild curiosity and friendliness, not averting her gaze. Towards the end of his career, Bouguereau painted many rustic genre scenes that proved immensely popular with collectors, including various works on the "shepherdess" theme. At the Salon and through the endeavors of his dealer Adolphe Goupil, viewers were charmed by the artists' depictions of rural labor, especially when co-mingled with images of young girls at play. Bouguereau offered a more sentimental vision of peasant life than Realist painters such as Courbet and Millet, as indicated by works such as The Young Shepherdess. But again, his mastery of naturalistic figure painting cannot be questioned. In practical terms, the painting's protagonist is based on one of the Italian immigrant girls whom Bouguereau hired as models during family summers in La Rochelle. The girls received a monthly salary, participated in household chores, and ate meals with his family. Art historians are divided on whether Bouguereau simply pandered to the market with his genre painting, or whether he elevated the peasantry with his love for their nobility and humility. John House describes Bouguereau's genre scenes as "broadly idealist ... treating his peasant women as if they were Raphael Madonnas." On the other hand, he lent distinctive personalities to some of his peasant girls, complicating his general commercializing attitude to the Naturalist style. In any case, Bouguereau's stance on the underclass never took a strong moral or sociological position like that of his contemporaries, and his politics - when directly expressed - tended towards conservatism.

See the curated highlights of Bouguereau's oeuvre.