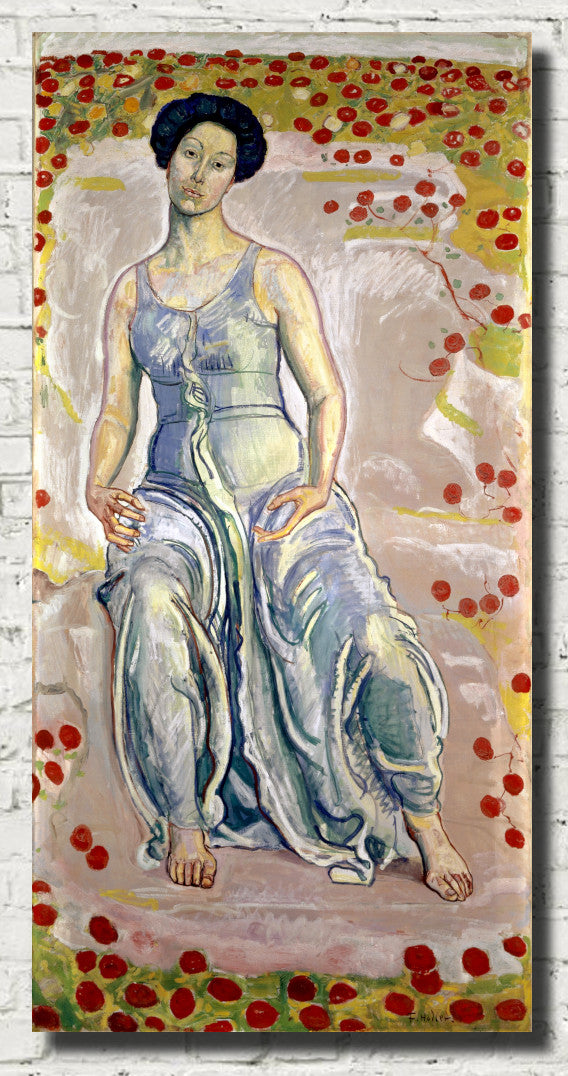

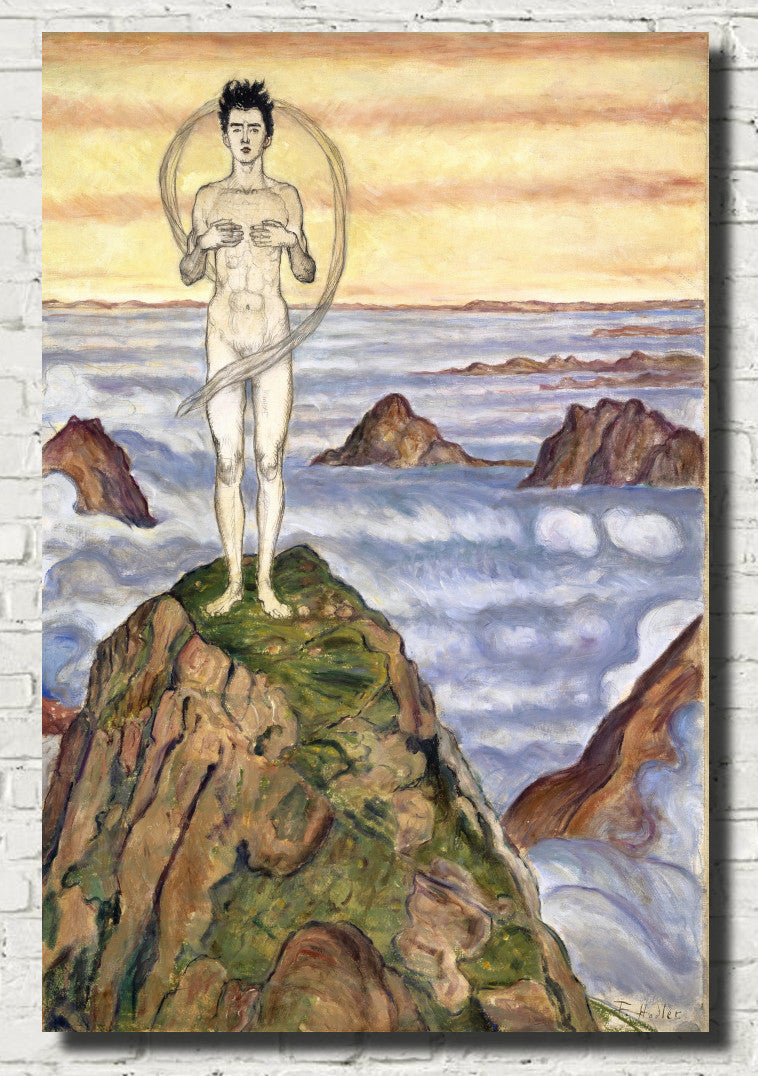

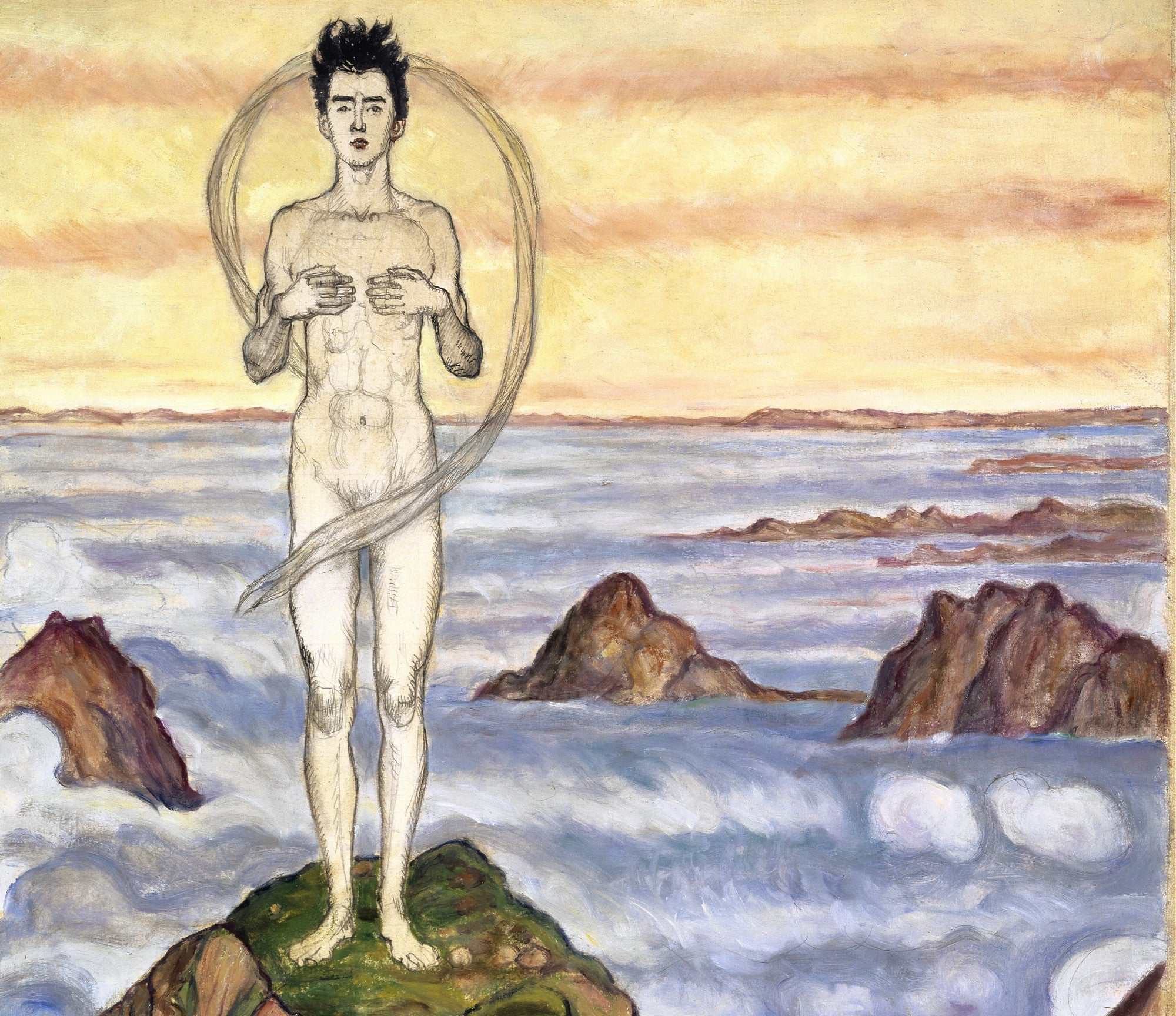

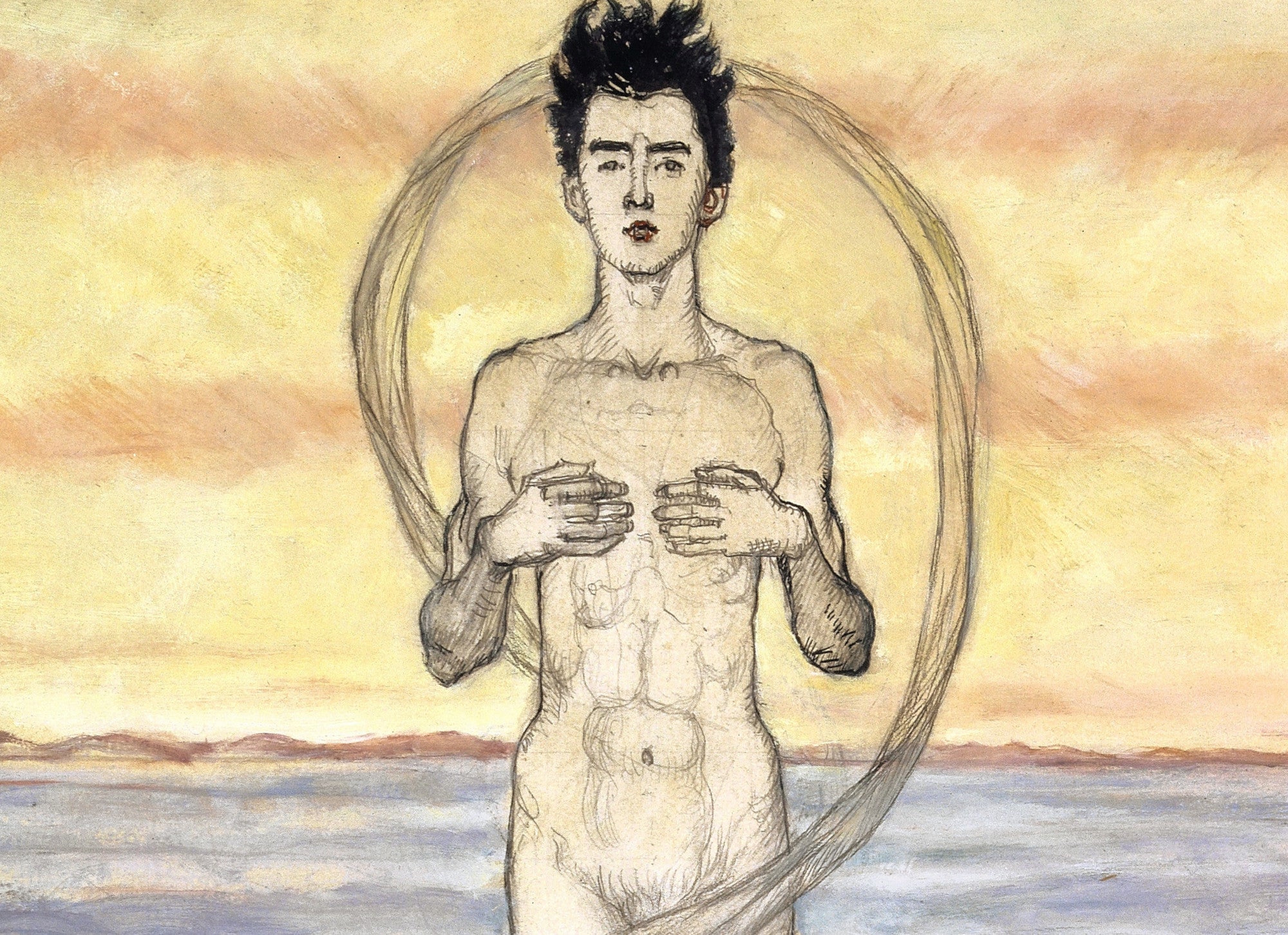

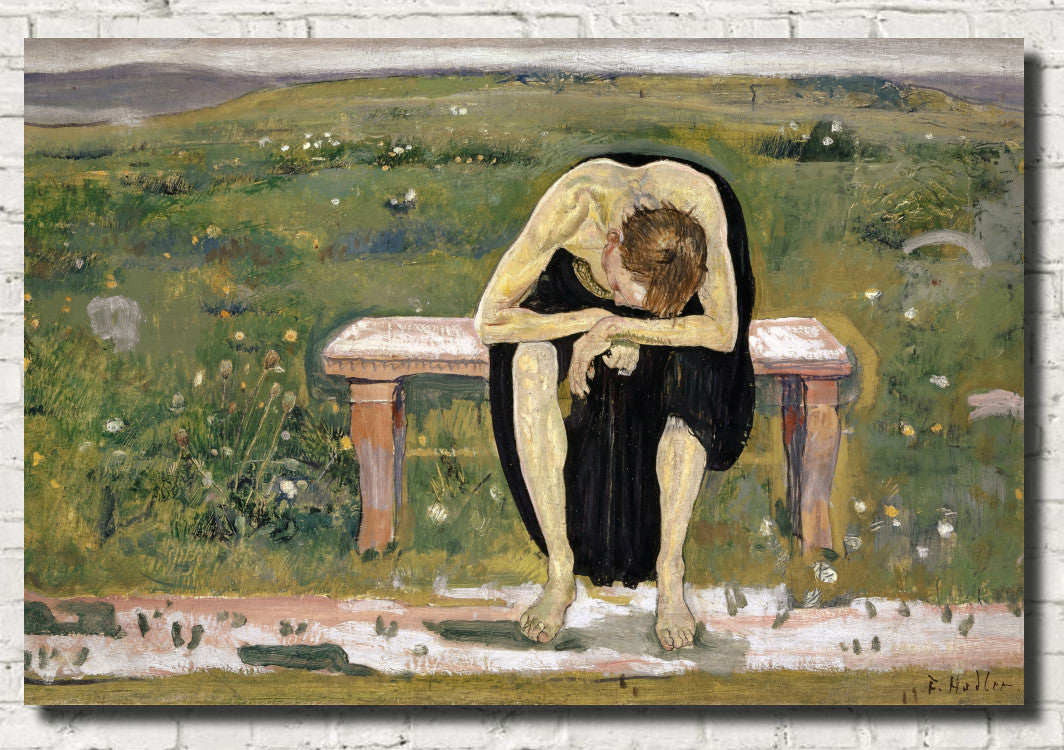

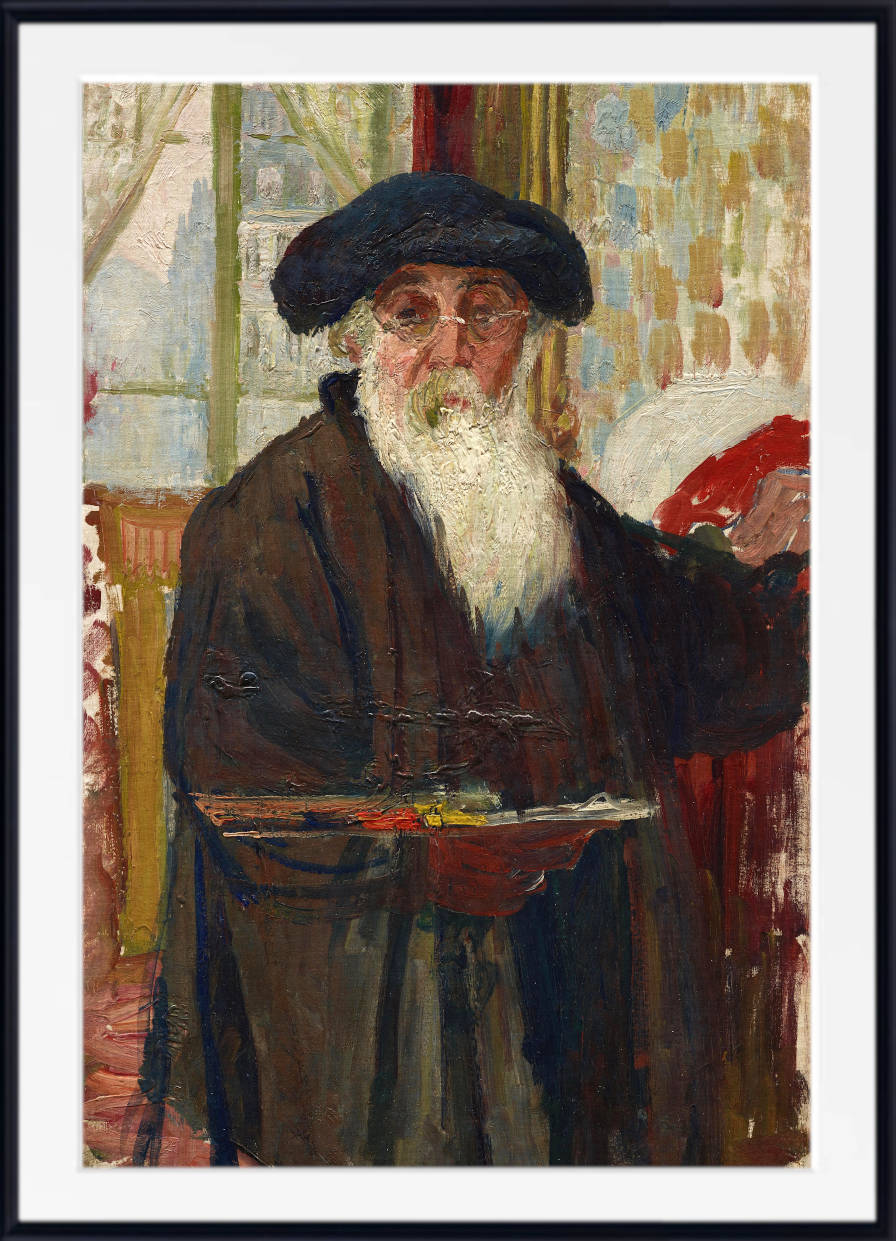

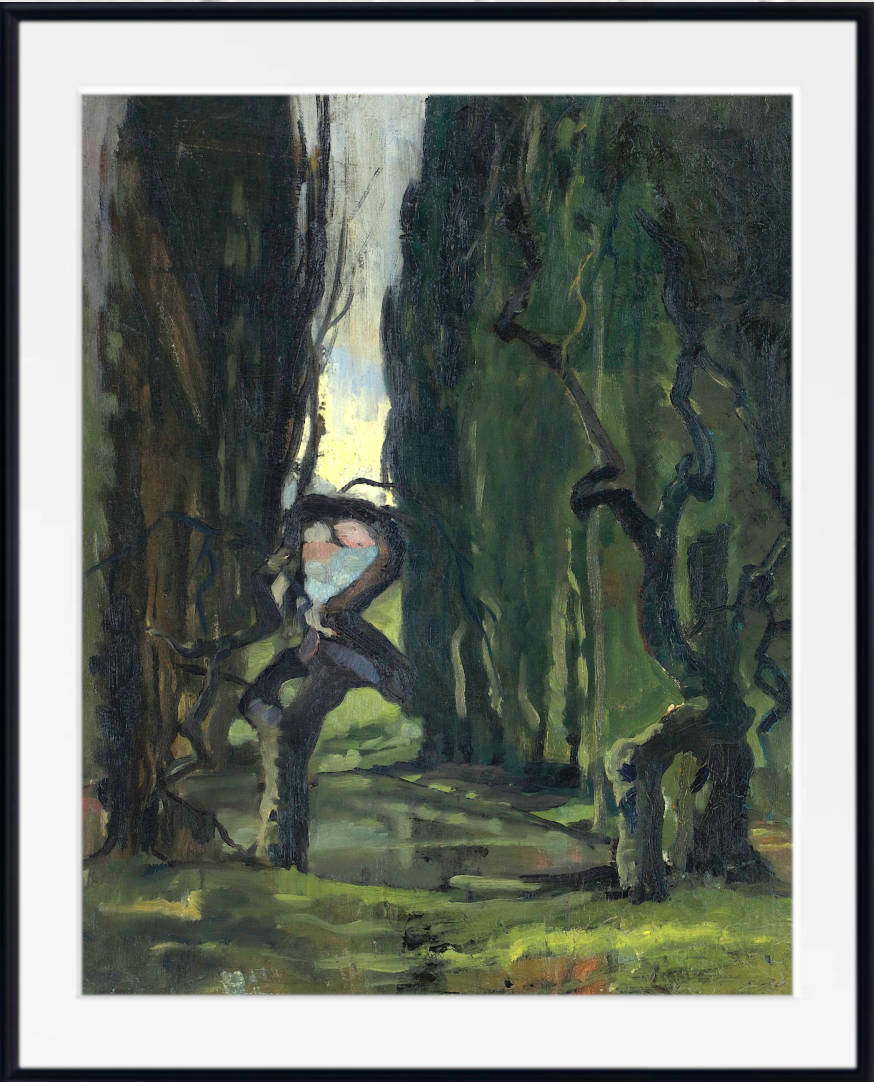

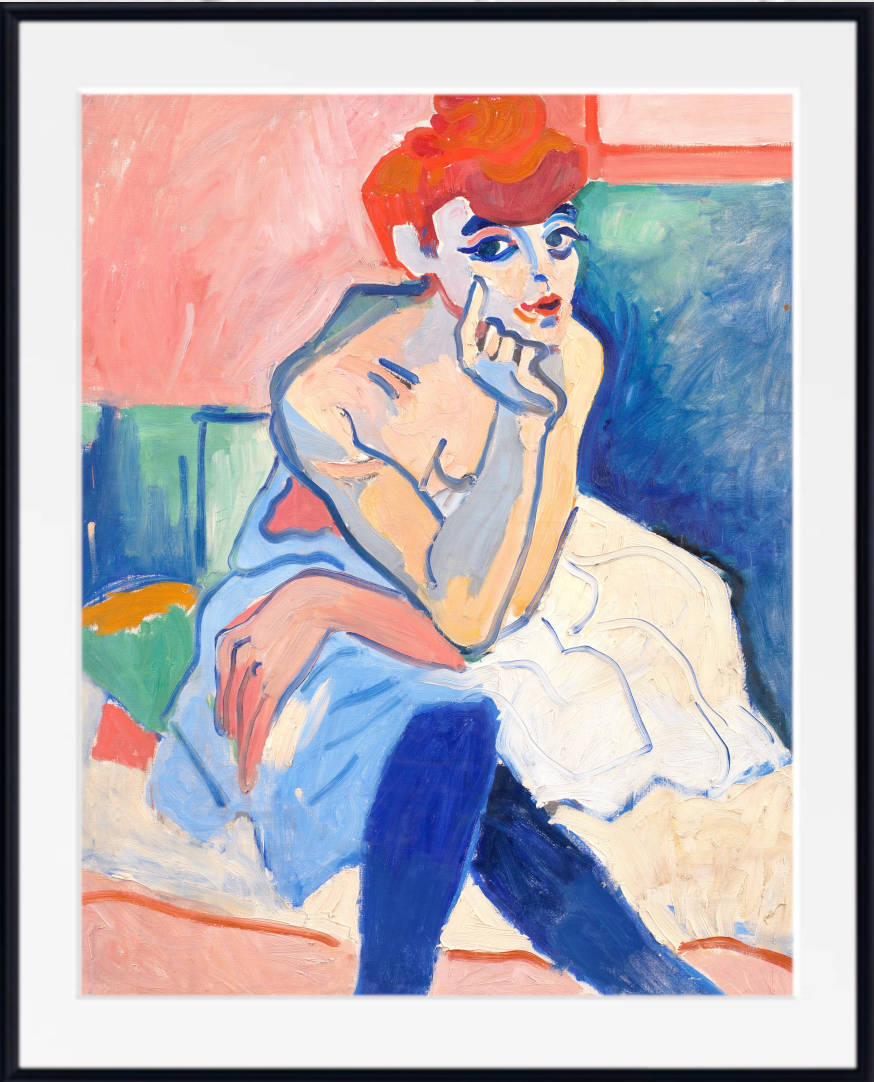

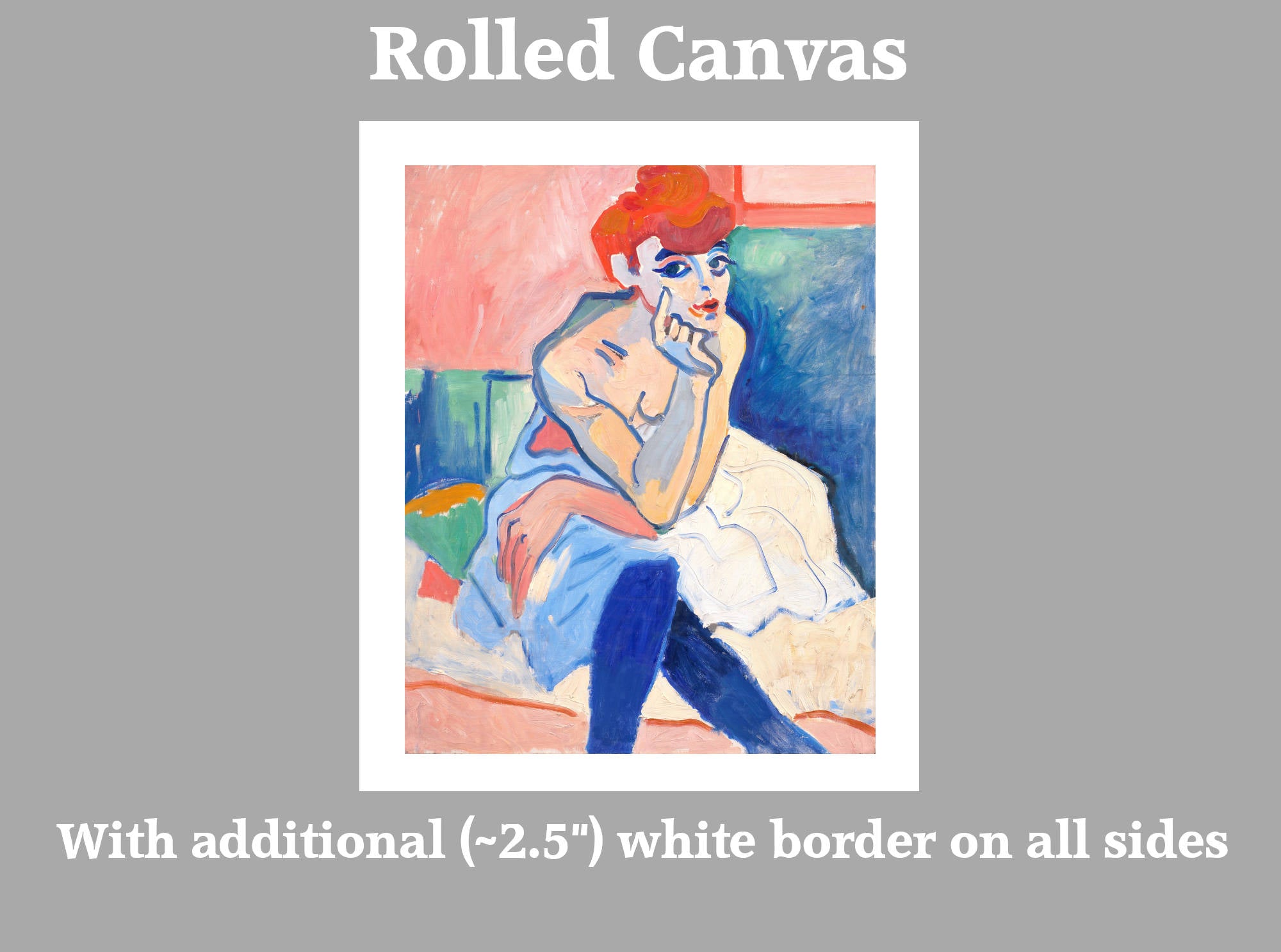

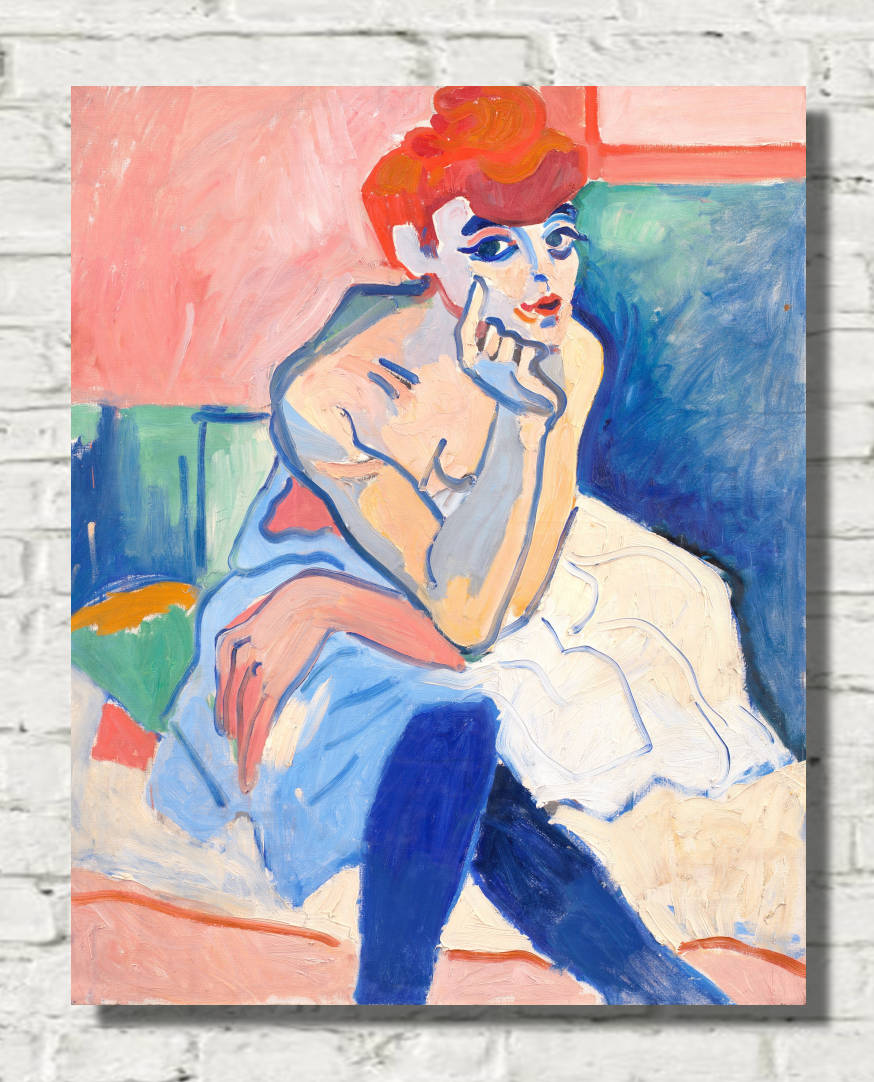

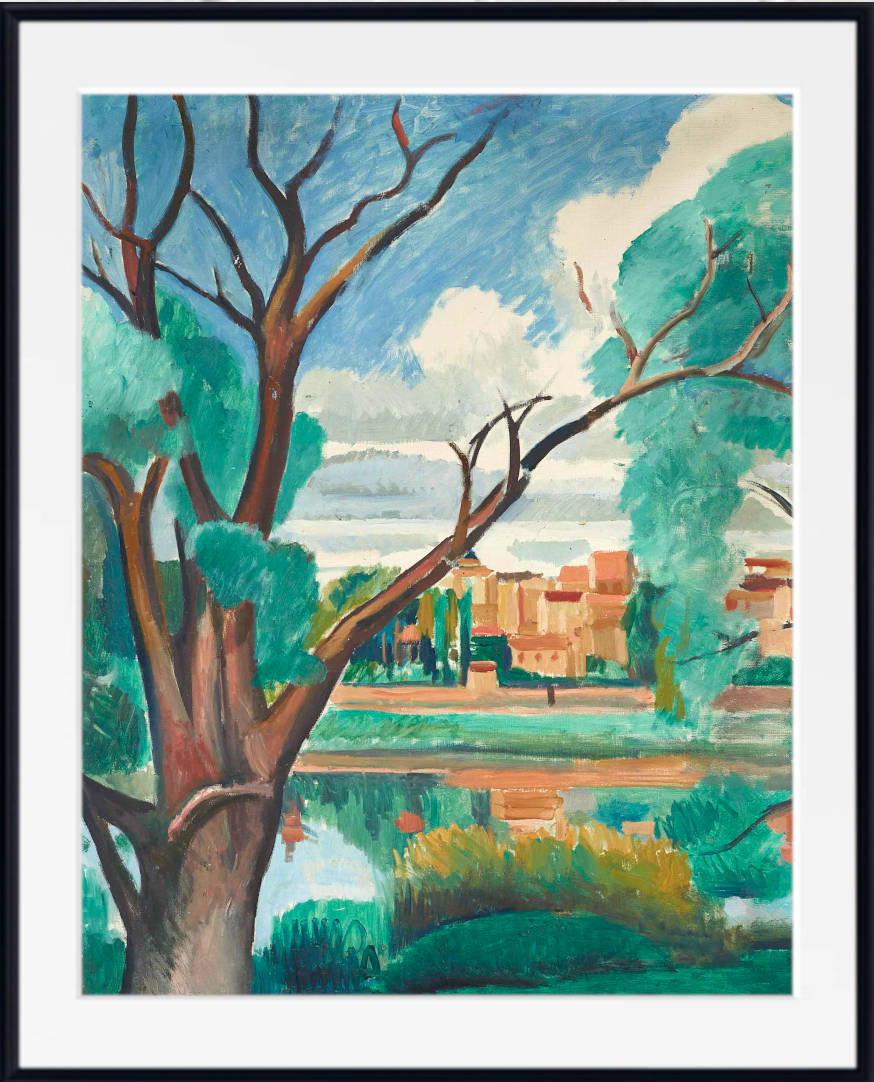

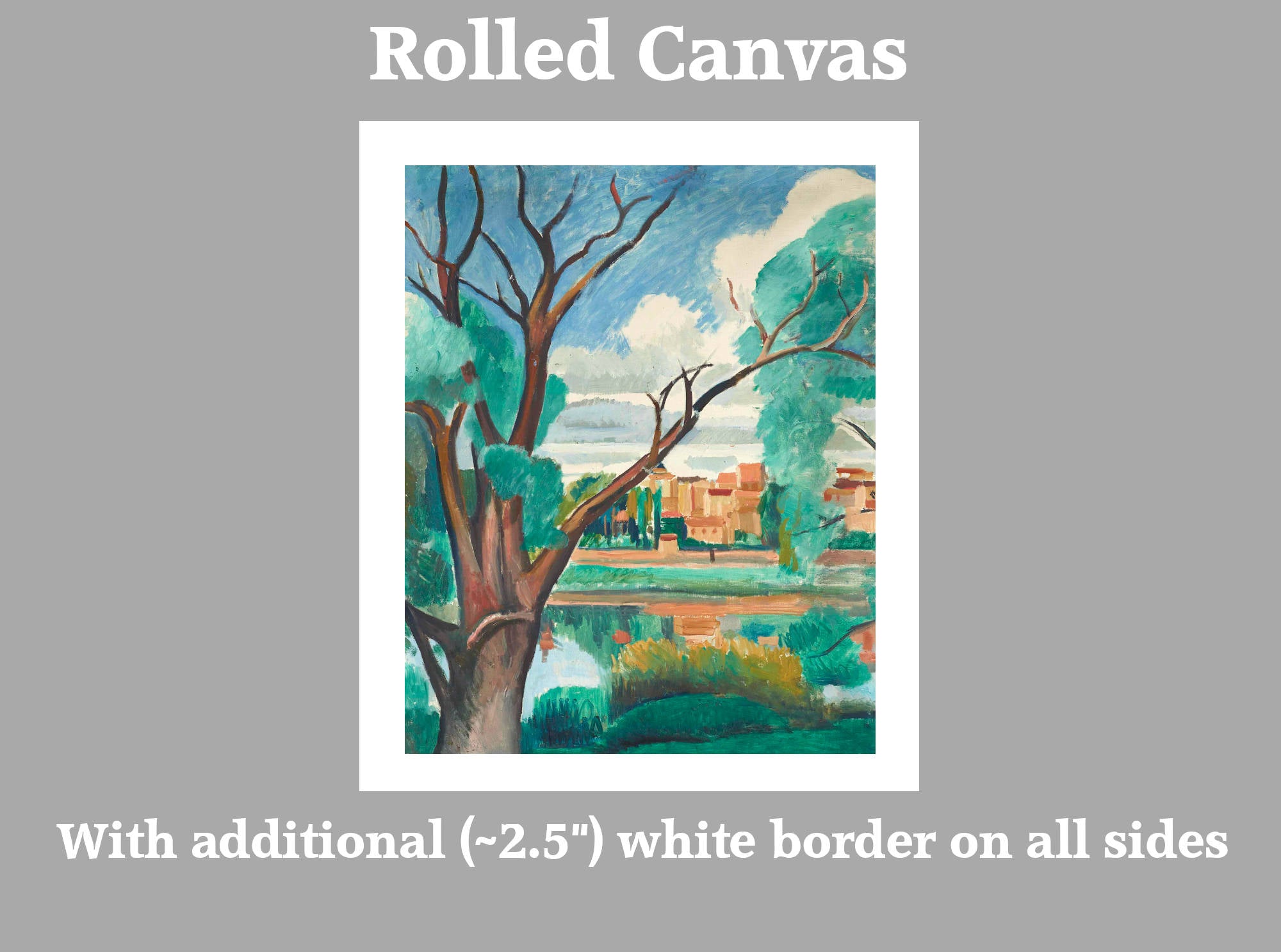

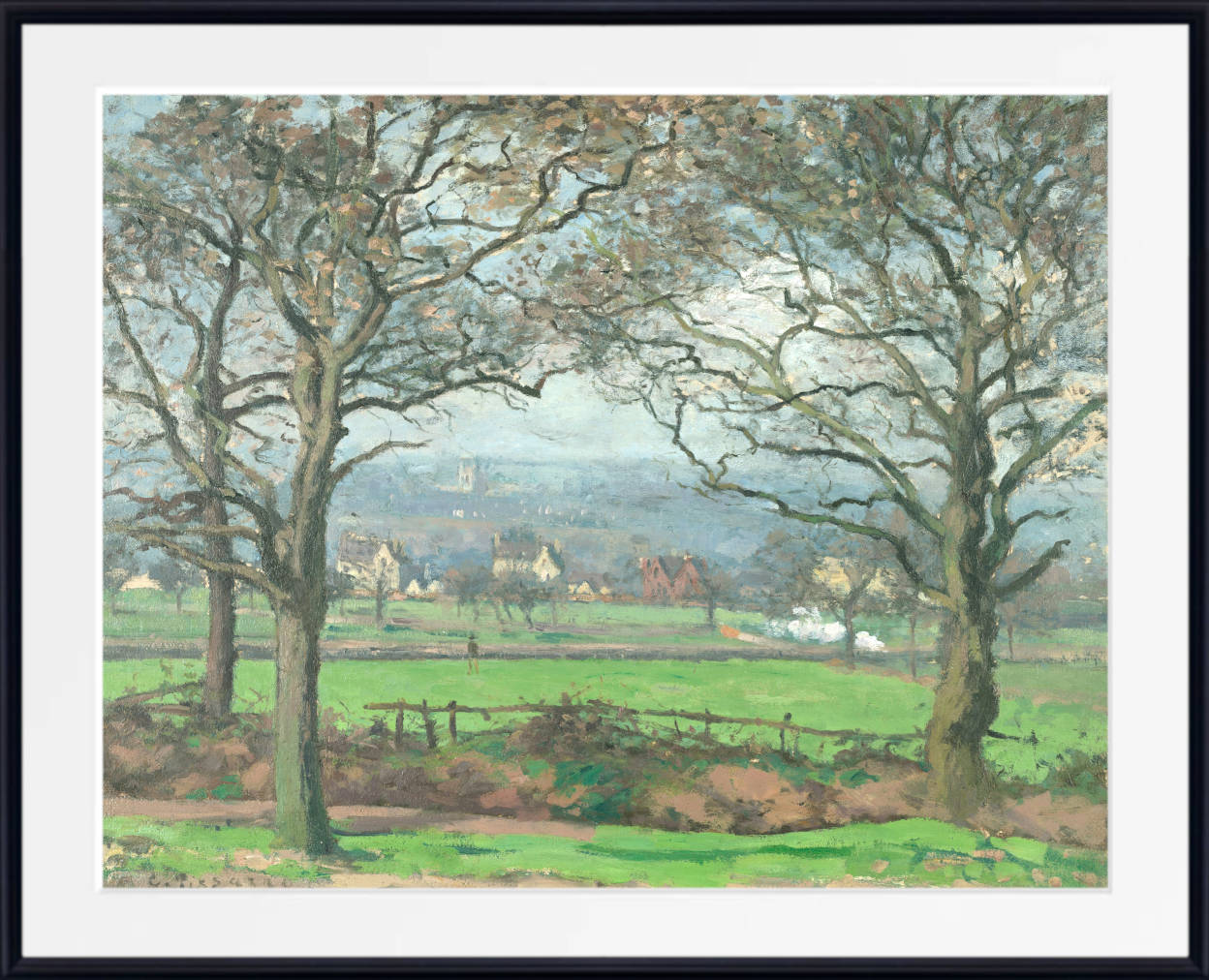

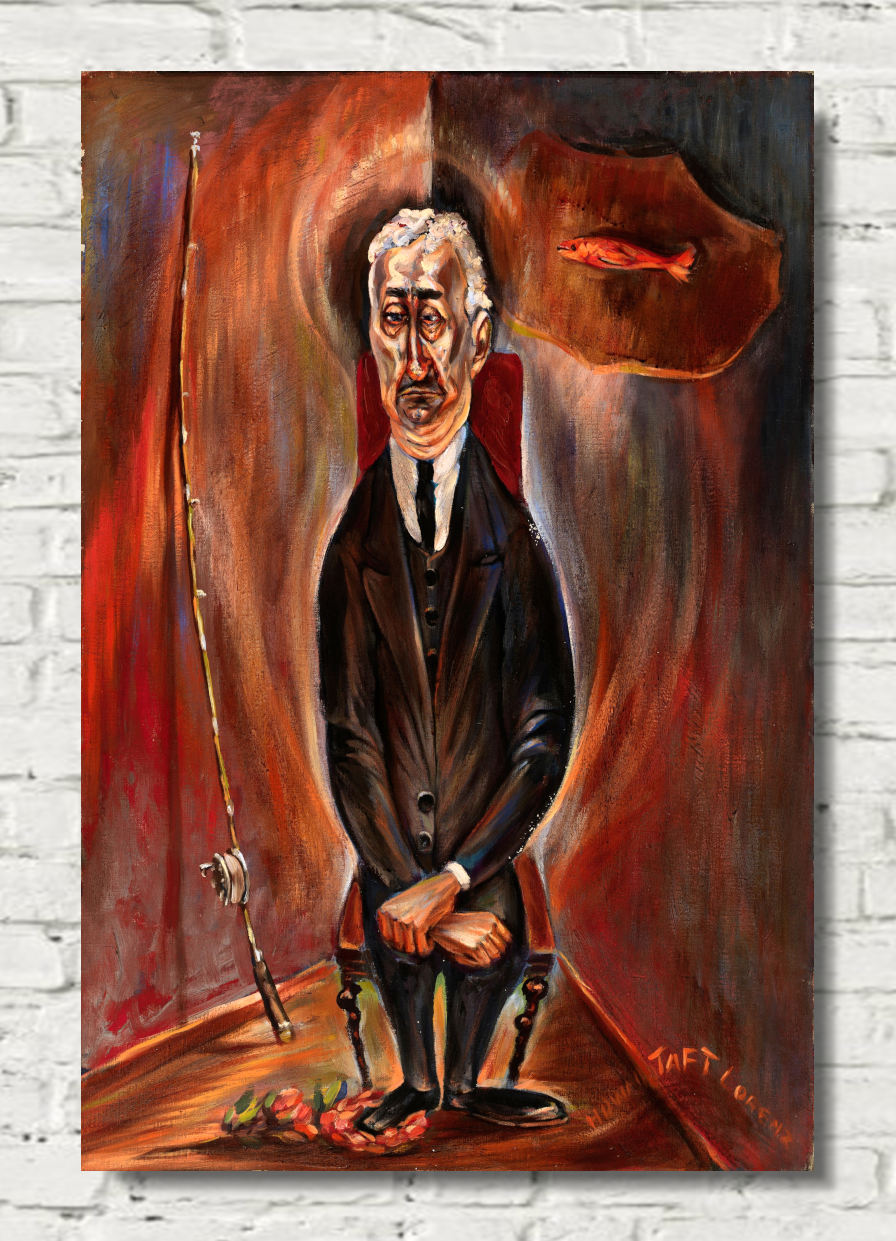

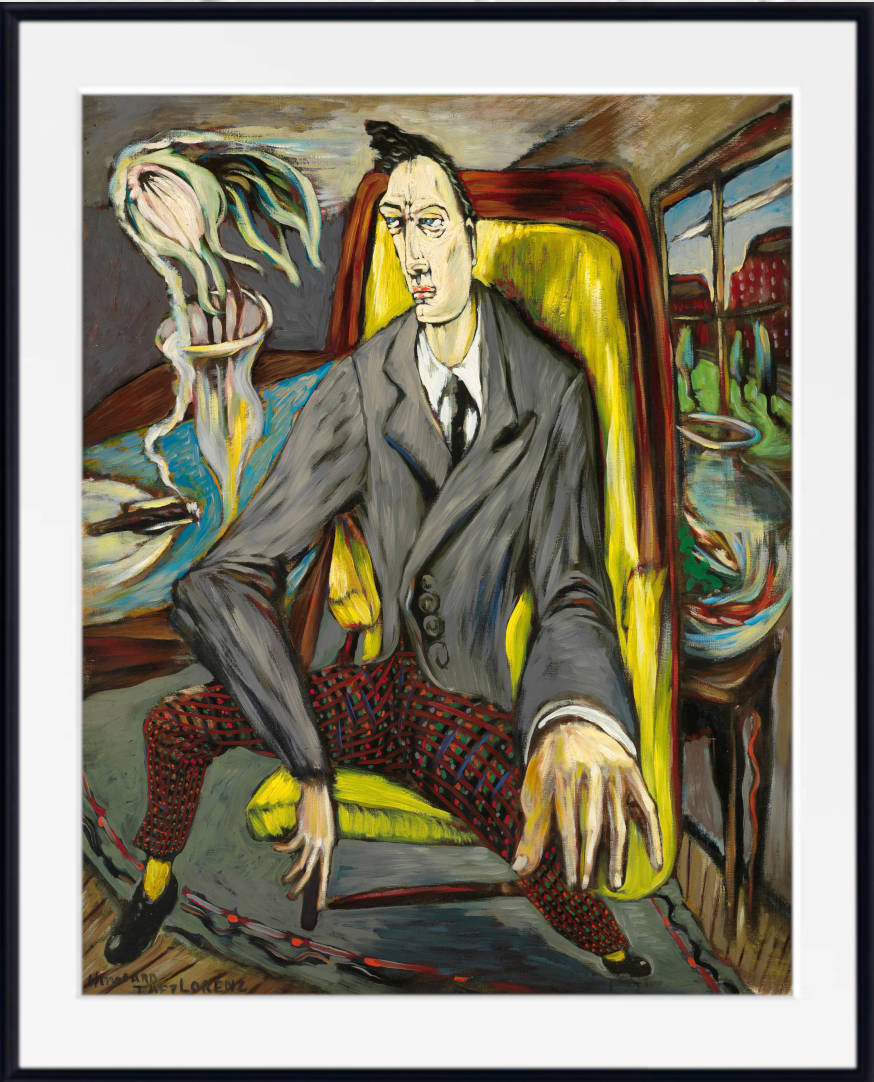

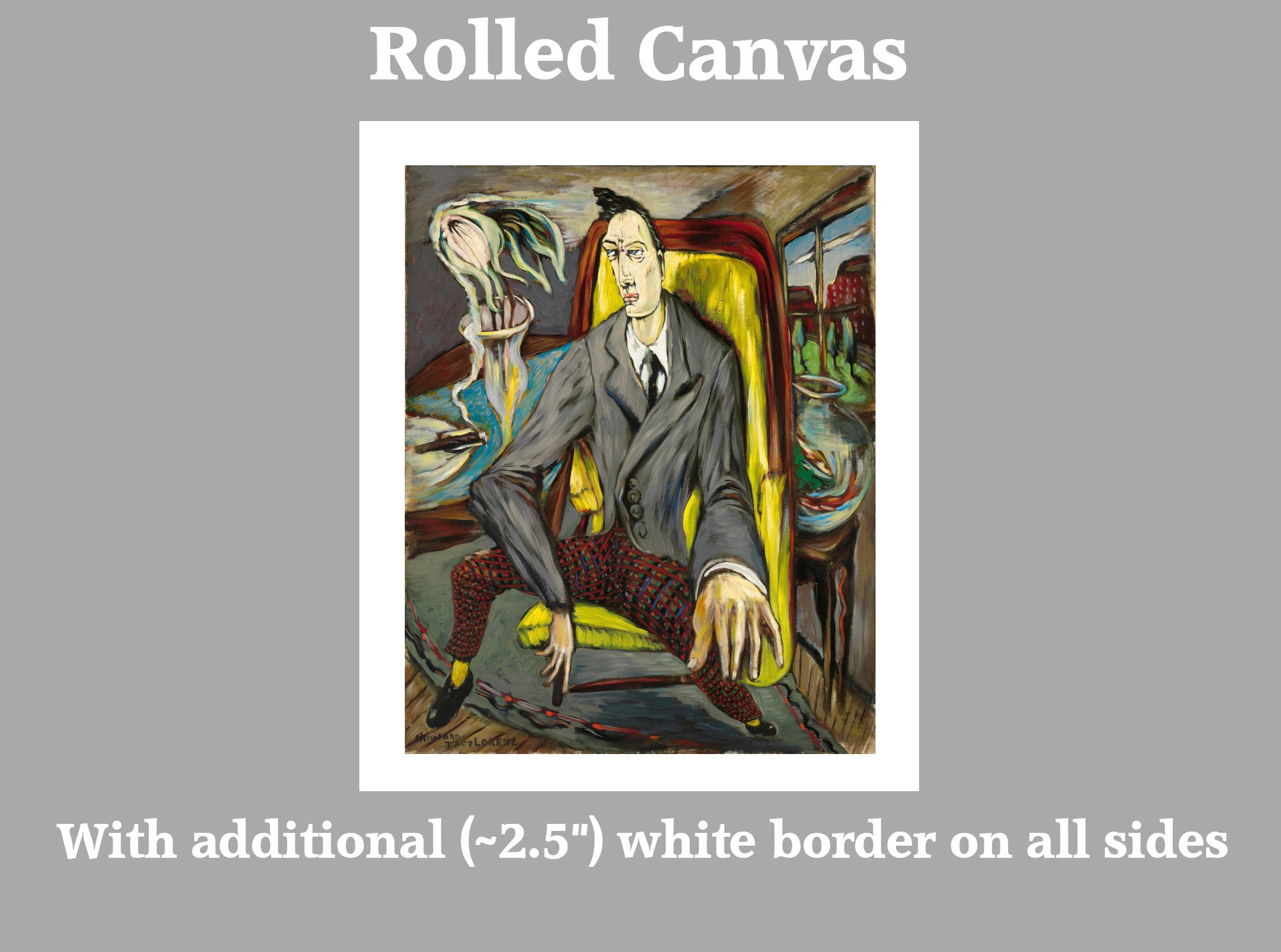

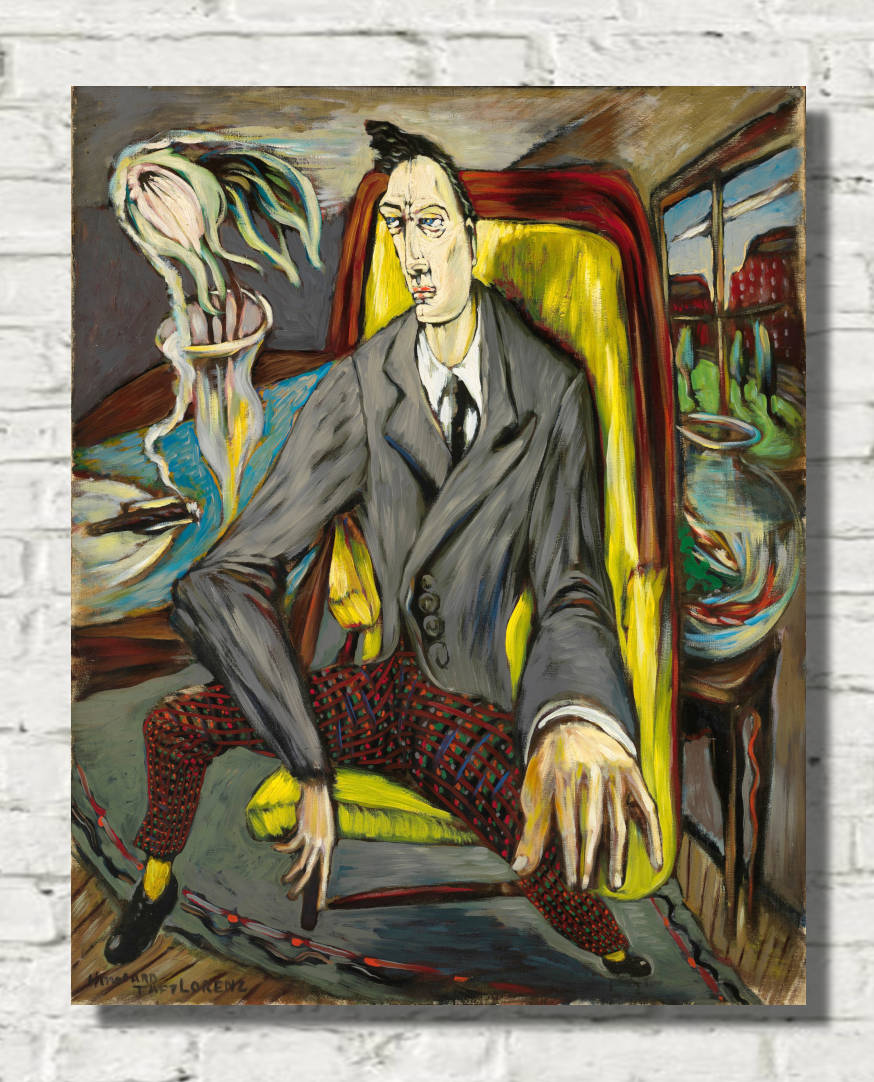

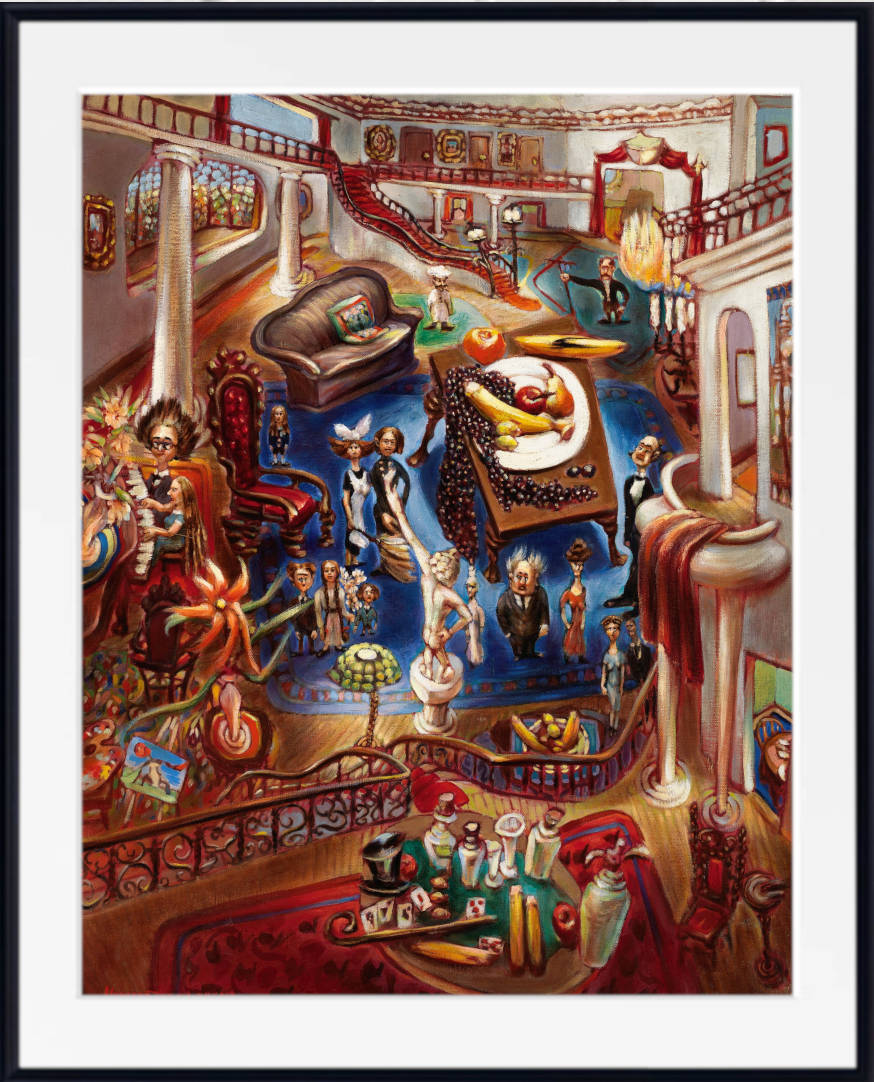

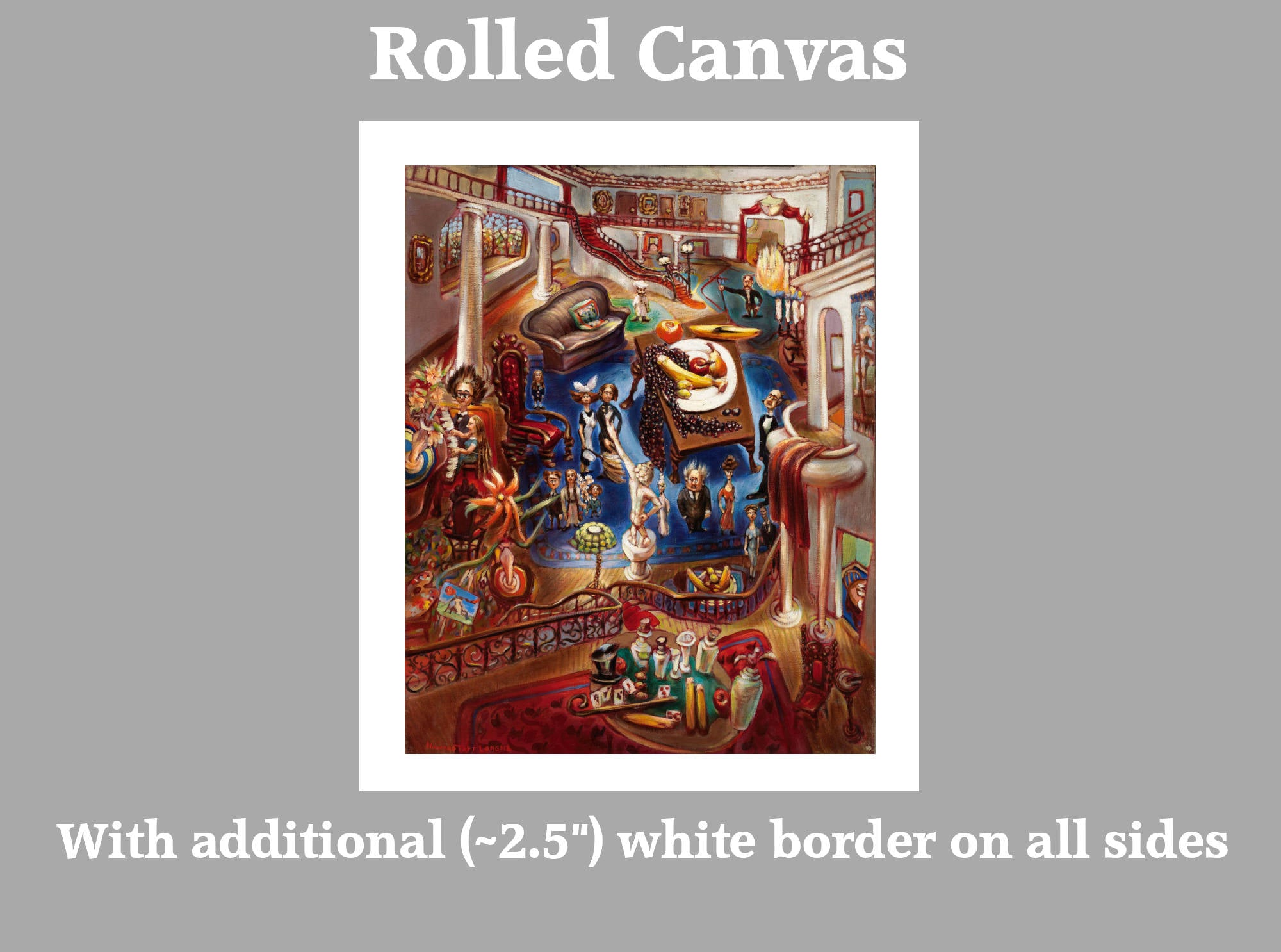

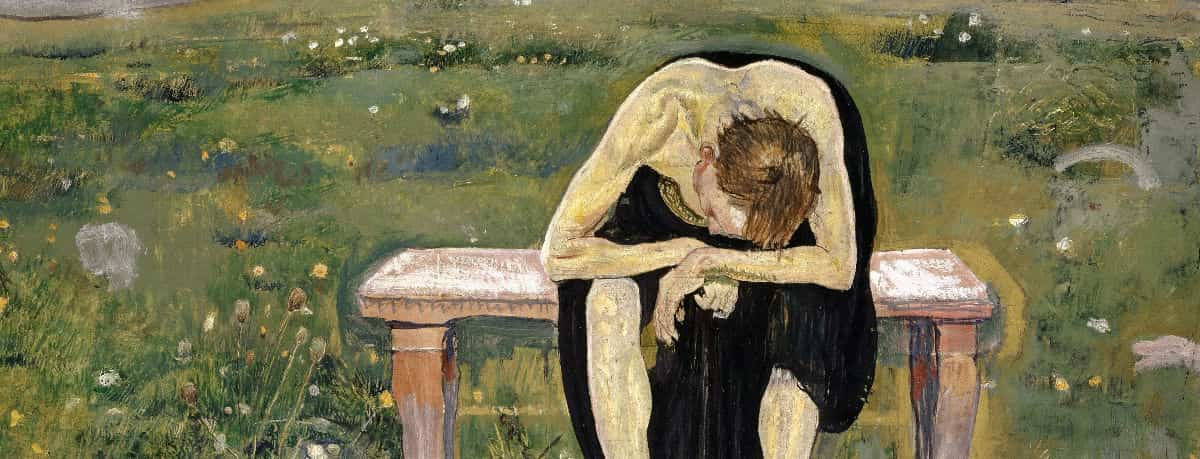

Ferdinand Hodler Prints

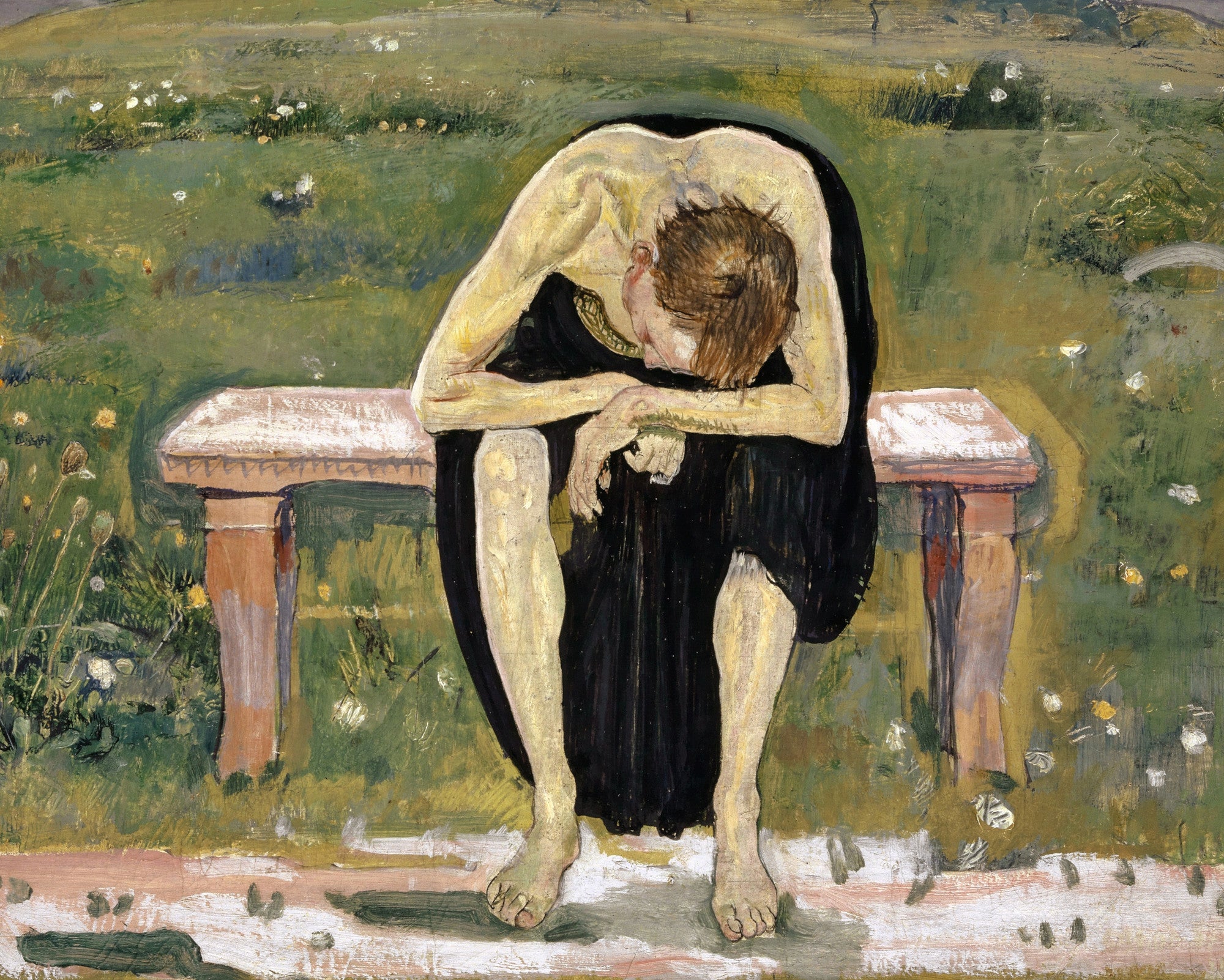

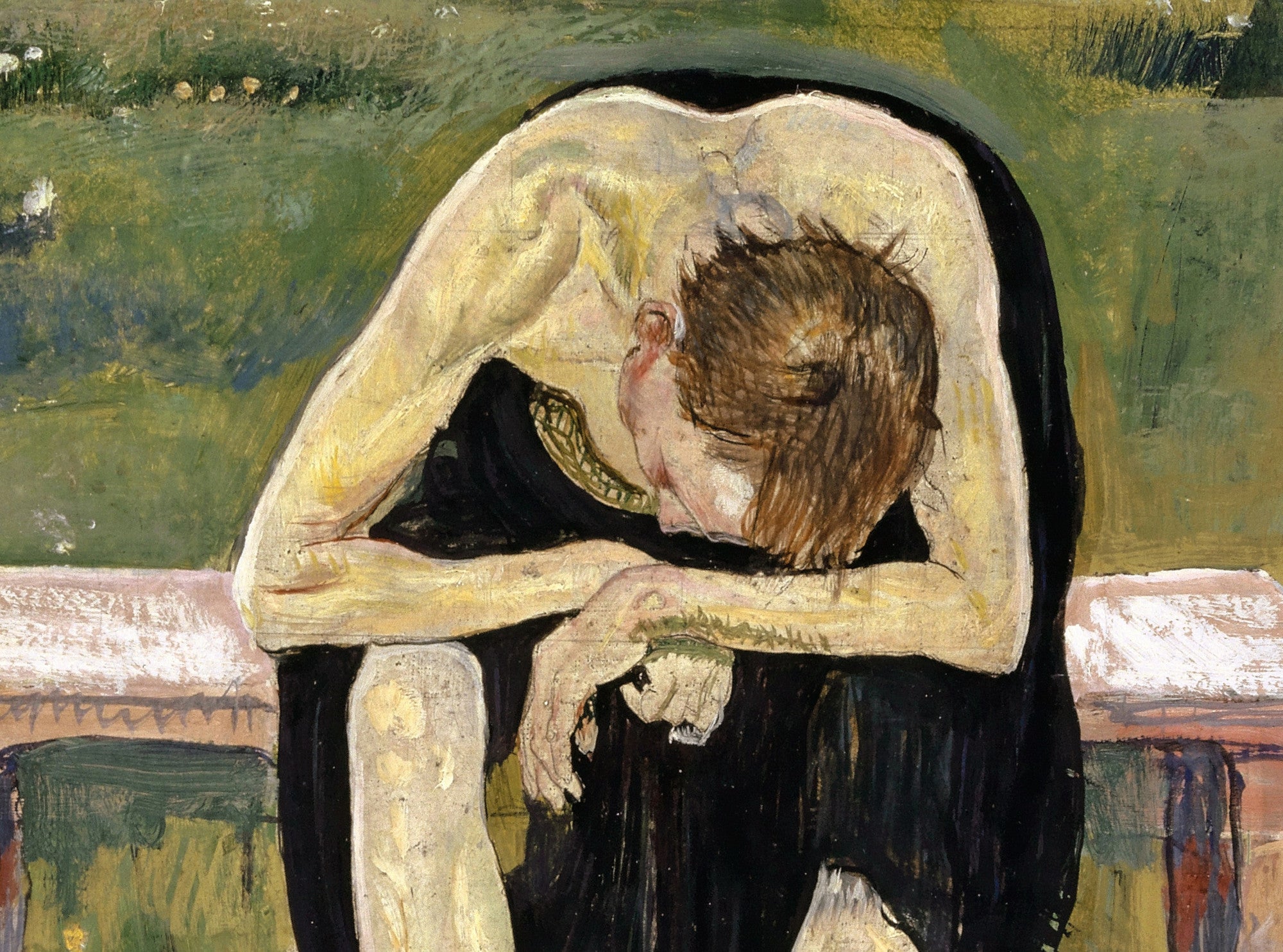

Ferdinand Hodler, a Swiss artist, masterfully blended Symbolism and modernist aesthetics. His serene landscapes and emotional figurative works reflect personal tragedy and a reverence for nature. Influential across Europe, Hodler's bold use of form and color anticipated modernism, leaving a lasting legacy despite critical challenges in his homeland.